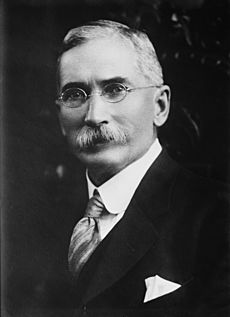

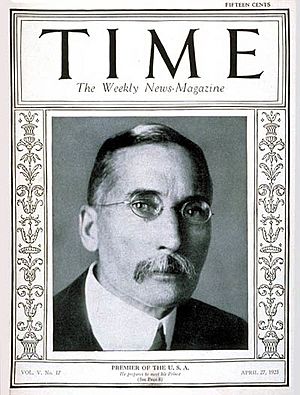

J. B. M. Hertzog facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

General The Right Honourable

J. B. M. Hertzog

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 3rd Prime Minister of South Africa | |

| In office 30 June 1924 – 5 September 1939 |

|

| Monarch | George V Edward VIII George VI |

| Governor-General | 1st Earl of Athlone 6th Earl of Clarendon Sir Patrick Duncan |

| Preceded by | Jan Christiaan Smuts |

| Succeeded by | Jan Christiaan Smuts |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Barry Munnik Hertzog

3 April 1866 Wellington, Cape Colony |

| Died | 21 November 1942 (aged 76) Pretoria, Transvaal, South Africa |

| Political party | National United |

| Spouse | Wilhelmina Neethling |

| Alma mater | Victoria College University of Amsterdam |

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog (born 3 April 1866 – died 21 November 1942) was a famous South African politician and soldier. Many people knew him as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog. He was a general during the Second Boer War and later became the third prime minister of the Union of South Africa. He served in this important role from 1924 to 1939. Throughout his life, Hertzog worked hard to support and grow the Afrikaner culture. He wanted to make sure Afrikaners kept their own traditions and were not too much like British culture.

Contents

Early Life and Start of Career

Hertzog first studied law at Victoria College in Stellenbosch, which was then part of the Cape Colony. In 1889, he travelled to the Netherlands to continue his law studies at the University of Amsterdam. He earned his doctorate in law there in 1892.

After his studies, Hertzog worked as a lawyer in Pretoria. In 1895, he became a judge in the Orange Free State. During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), he became a general. He was an assistant chief leader of the Orange Free State's military units, called Commandos. He was known as a clever leader, especially among the "bitter-enders" who wanted to keep fighting. However, he eventually agreed that fighting more was pointless and signed the Treaty of Vereeniging in May 1902, which ended the war.

Beginning of His Political Journey

After the war, Hertzog entered politics. He helped create the Orangia Unie Party. In 1907, the Orange River Colony became self-governing. Hertzog joined the government as the Attorney-General and Director of Education. He strongly believed that both Dutch and English should be taught in schools, which caused some arguments.

Later, he became the national Minister of Justice in the new Union of South Africa in 1910. He stayed in this job until 1912. He often disagreed with the British authorities and the Prime Minister, Louis Botha. This led to a government crisis. In 1913, Hertzog left the South African Party and formed his own group, made up of older Boer and anti-British members.

When the Maritz Rebellion started in 1914, Hertzog chose to stay neutral. After the war, he led the group that opposed the government of General Smuts.

Becoming Prime Minister

First Government (1924-1929)

In the election of 1924, Hertzog's National Party won. They teamed up with the Labour Party to form a government known as the Pact Government. In 1934, the National Party and the South African Party joined together to create the United Party. Hertzog became the Prime Minister and leader of this new party.

As prime minister, Hertzog introduced many new laws to help white working-class people. His government set up a Department of Labour. The Wages Act (1925) set minimum wages for some workers, but not for farm workers or domestic helpers. It also created a Wage Board to control pay. The Old Age Pensions Act (1927) gave retirement money to white workers. Coloured people also received pensions, but their amount was less than for white people.

Second Government (1929-1933)

The creation of the South African Iron and Steel Industrial Corp in 1930 helped the economy grow. Removing taxes on imported raw materials also helped industries develop and create jobs. The government also helped farmers by guaranteeing prices for their products and offering loans.

Laws were improved to protect workers, including those for miners with lung diseases. White city renters also got more protection against being evicted. The government also made it easier for Afrikaners to join the civil service by promoting both English and Afrikaans. White women were given the right to vote in 1930. The government also improved postal services and started an experimental airmail service.

In 1937, a separate Department of Social Welfare was created to deal with social issues. Money spent on education for both white and Coloured children increased. Spending on Coloured education went up by 60%, leading to 30% more Coloured children attending school. Grants for blind and disabled people were introduced in 1936 and 1937. Unemployment benefits also started in 1937.

However, these policies mostly helped white South Africans. They also introduced laws that made it harder for black workers to find jobs. This was called the Civilised Labour Policy. It aimed to replace black workers with white workers, especially poor Afrikaners. Laws like the Industrial Conciliation Act (1924) and the Mines and Works Amendment Act (1926) created job reservations for white people and limited black workers' rights. These policies set the stage for the later Apartheid system.

Hertzog believed in making South Africa more independent from the British Empire. His government approved the Statute of Westminster 1931 in 1931, which gave South Africa more control over its own laws. In 1925, Afrikaans replaced Dutch as the second official language. A new national flag was introduced in 1928.

In 1930, white women gained the right to vote, which strengthened the power of the white minority. Voting rules for white people became easier, but for non-white people, they became much stricter. In 1936, black people were completely removed from the common voter's roll. Instead, they had their own separate representatives. This gradual removal of voting rights for non-white people continued until 1970.

Third Government (1933-1938)

In foreign policy, Hertzog wanted South Africa to be less involved with the British Empire. He was also sympathetic towards Germany and believed the Treaty of Versailles (which ended World War I) was unfair to Germany. Hertzog's government had different views on foreign policy. Some, like Smuts, were pro-British, while others, like Oswald Pirow, were pro-German. Hertzog tried to find a middle ground.

Hertzog believed that Nazi Germany was a "normal state" and a possible friend, unlike the Soviet Union, which he saw as a threat. He thought that if Germany's complaints about the Treaty of Versailles were addressed, Adolf Hitler would become a more reasonable leader. When Germany sent troops into the Rhineland in 1936, Hertzog told the British government that South Africa would not get involved if Britain went to war over it.

Hertzog's main advisor on foreign affairs was H.D.J. Bodenstein, who was anti-British. The South African minister in Berlin, Stefanus Gie, also sent reports that painted Germany in a good light. These reports helped support Hertzog's foreign policy choices.

In 1938, Hertzog stated that South Africa would not fight in any "unjust" wars. He said that if Britain chose to go to war over events in Czechoslovakia, South Africa would stay neutral. He believed that Eastern Europe was rightfully Germany's area of influence.

Fourth Government (1938-1939)

In 1938, as Britain was close to war with Germany over the Sudetenland (a part of Czechoslovakia), Hertzog and Smuts disagreed. Hertzog wanted South Africa to be neutral, while Smuts wanted to support Britain. Hertzog suggested a compromise: South Africa would be neutral but in a way that still favoured Britain.

When Hitler rejected a peace plan, putting Europe on the edge of war, Hertzog believed that Germany was not to blame. He thought the differences were small and not worth a war. He continued to argue that Czechoslovakia and France were causing problems and that Britain should pressure them to make more concessions to Germany.

On 28 September 1938, Hertzog got his government to agree to a policy of pro-British neutrality, meaning South Africa would only go to war if Germany attacked Britain first. He strongly approved of the Munich Agreement (30 September 1938), which he saw as a fair solution to the German-Czechoslovak dispute.

However, on 4 September 1939, the United Party disagreed with Hertzog's idea of neutrality in World War II. His government lost a vote in parliament. The Governor-General, Sir Patrick Duncan, refused Hertzog's request to hold a new election. Hertzog resigned, and Smuts became prime minister, leading South Africa into the war. Hertzog later joined a new party, the Herenigde Nasionale Party, and became the Leader of the Opposition. But he soon lost support and retired from politics.

Death and What He Left Behind

Hertzog passed away on 21 November 1942, at the age of 76.

A large statue of Hertzog was put up in 1977 at the Union Buildings in Pretoria. In 2013, this statue was moved to a new spot in the gardens to make way for a larger statue of Nelson Mandela.

Hertzog's supporters created a sweet treat called the Hertzoggie. It's a small tart with jam and a coconut meringue topping, and it's still a popular dessert in South Africa today.

He is the only South African Prime Minister who served under three different kings: George V, Edward VIII, and George VI. This happened because he was in office during the year 1936, when the throne changed hands twice.

|

See also

In Spanish: Barry Hertzog para niños

In Spanish: Barry Hertzog para niños