Afrikaans facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Afrikaans |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native to | South Africa, Namibia | |||

| Native speakers | 6.86 million (South Africa) (2011 Census) Total: 15–23 million |

|||

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

| Recognised minority language in | ||||

| Regulated by | Die Taalkommissie | |||

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-ba | |||

|

||||

|

||||

Afrikaans is a West Germanic language that grew from Dutch spoken in the Dutch Cape Colony. This happened in what is now South Africa. Settlers from the Netherlands, France, and Germany spoke it, along with the people they enslaved.

About 90% to 95% of Afrikaans words come from Dutch. It also has words from other languages like German and the Khoisan languages of Southern Africa.

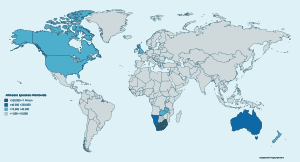

Today, Afrikaans is spoken in South Africa, Namibia, and a bit in Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Around 15 to 23 million people speak Afrikaans. In South Africa, about 7 million people (13.5% of the population) speak it as their first language. This makes it the third most common native language there, after Zulu and Xhosa.

Many universities outside South Africa teach Afrikaans. These include schools in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Russia, and the United States.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name "Afrikaans" comes from the Dutch word Afrikaansch, which means "African."

Before, people called it "Cape Dutch." This name was also used for the early settlers. Some even called it "kitchen Dutch," which was a rude term. It referred to how enslaved people used the language in the kitchen.

How Afrikaans Grew

Where it Started

Afrikaans began in the Dutch Cape Colony. It slowly changed from the Dutch spoken in Europe during the 1700s.

Some experts believe modern Afrikaans came from two sources:

- Cape Dutch: This was the Dutch language brought directly from Europe to Southern Africa.

- Hottentot Dutch: This was a simpler form of Dutch. It was used by enslaved people and others who learned Dutch as a second language.

So, Afrikaans is a mix of these two ways of speaking.

How it Developed

Many early settlers who became the Afrikaners came from the Netherlands. Some were French Huguenots, and others were from Germany.

African and Asian workers, children of European settlers and Khoikhoi women, and enslaved people all helped Afrikaans grow. The enslaved people came from places like East Africa, West Africa, India, Madagascar, and Indonesia. Many Khoisan people also helped. They were good at translating and worked as servants. Many free and enslaved women married or lived with Dutch settlers.

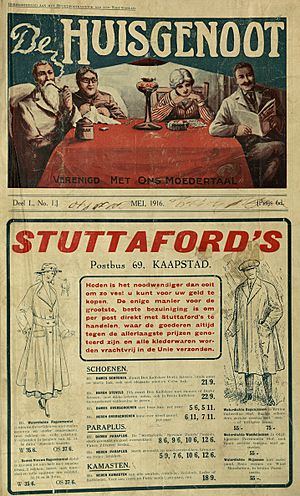

Around 1815, Afrikaans started to be used in Muslim schools in South Africa. At first, it was written using the Arabic alphabet. Later, Afrikaans began appearing in newspapers and books around 1850. By then, it was written with the Latin script.

In 1875, a group of Afrikaans speakers formed the Genootskap vir Regte Afrikaaners (meaning "Society for Real Afrikaners"). They published books in Afrikaans, including grammars and dictionaries.

For a long time, Afrikaans was seen as just a type of Dutch. People thought it was not suitable for educated conversations. They called it a "kitchen language," used mainly between farmers and their servants.

Becoming Official

In 1925, the South African government officially recognized Afrikaans as its own language. This happened 23 years after the Second Boer War. The Official Languages of the Union Act of 1925 made Afrikaans a type of Dutch.

Later, the Constitution of 1961 made English and Afrikaans the official languages. It said that Afrikaans included Dutch. The Constitution of 1983 then removed any mention of Dutch.

The Afrikaans Language Monument is a special place that celebrates the language. It is located on a hill in Paarl, South Africa. It opened in 1975, 100 years after the Society of Real Afrikaners was founded. It also marked 50 years since Afrikaans became an official language.

How Afrikaans Works

In Afrikaans, verbs don't change much. For example, the verb "to be" (wees) and "to have" (hê) are special.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| wees | zijn | be |

| hê | hebben | have |

Most verbs stay the same no matter who is doing the action.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| ek is | ik ben | I am |

| jy/u is | jij/u bent | you are (singular) |

| hy/sy/dit is | hij/zij/het is | he/she/it is |

Afrikaans often uses a "double negative." This means using "not" twice in a sentence. It's different from English.

- Afrikaans: Hy kan nie Afrikaans praat nie

- English: He cant speak Afrikaans.

This double negative is a normal part of Afrikaans grammar.

Some words in Afrikaans are shortened. For example, moet nie (must not) usually becomes moenie. It's like how "do not" becomes "don't" in English.

Different Kinds of Afrikaans

Experts used to think there were three main types of Afrikaans after the Great Trek in the 1830s: Northern Cape, Western Cape, and Eastern Cape. Today, these differences are less noticeable because of standard Afrikaans.

- Sabela: This is a secret language used in prisons. It's based on Afrikaans but has many words from Zulu.

Cape Afrikaans

Kaapse Afrikaans (Cape Afrikaans) is a special way of speaking in the Cape Peninsula of South Africa. It was once spoken by many different groups. Now, it's mostly used by the Cape Coloured community in Cape Town. Most Afrikaans speakers can still understand it.

Cape Afrikaans keeps some features that are more like Dutch than standard Afrikaans. For example, they might say ik for "I" instead of ek.

Orange River Afrikaans

Oranjerivierafrikaans (Afrikaans of the Orange River) refers to how standard Afrikaans is spoken in the Upington area of South Africa.

Patagonian Afrikaans

A unique type of Afrikaans is spoken by a small community of South Africans in Patagonia, Argentina.

Words from Other Languages

Afrikaans has borrowed many words from other languages.

Malay

The early Cape Malay community in Cape Town brought many Classical Malay words into Afrikaans.

- baie: means 'very' or 'much'. (from banyak)

- baadjie: means 'jacket'. (from baju)

- piesang: means 'banana'. (from pisang)

- piering: means 'saucer'. (from piring)

Portuguese

Some words came from Portuguese:

- sambreel: 'umbrella' (from sombreiro)

- kraal: 'pen' or 'cattle enclosure' (from curral)

- mielie: 'corn' (from milho)

Khoisan Languages

Words from Khoisan languages include:

- geitjie: 'lizard'

- gogga: 'insect'

- kierie: 'walking stick'

Bantu Languages

Words from Bantu languages often name local birds and plants:

- mahem: a type of crane

- maroela: a type of tree

- fundi: means an 'expert' (from Zulu umfundi meaning 'scholar')

- tjaila: means 'to go home' or 'finish work' (from Zulu chaile)

French

Many French Huguenots came to South Africa in the late 1600s. They influenced Afrikaans, especially with military words.

- alarm: 'alarm'

- bagasie: 'luggage'

- biblioteek: 'library'

- soldaat: 'soldier'

- tante: 'aunt'

How Afrikaans is Written

Afrikaans uses the 26 letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet. It also has 16 extra vowels with special marks called diacritics.

Sometimes, letters are dropped from the older Dutch spelling. For example, Dutch slechts (only) becomes slegs in Afrikaans. Also, the Dutch ij often becomes y in Afrikaans.

The word for "a" or "an" is 'n in Afrikaans. It's usually pronounced very softly.

A few short words in Afrikaans start with an apostrophe, like 'n. If such a word starts a sentence, the next word is capitalized.

Common Afrikaans Phrases

Here are some common phrases in Afrikaans:

| Afrikaans | English |

|---|---|

| Hallo! Hoe gaan dit? | Hello! How are you? |

| Baie goed, dankie. | Very well, thank you. |

| Praat jy Afrikaans? | Do you speak Afrikaans? |

| Ja. | Yes. |

| Nee. | No. |

| 'n Bietjie. | A bit. |

| Wat is jou naam? | What is your name? |

| Ek is lief vir jou. | I love you. |

In Dutch, the word Afrikaans means "African" in general. So, to avoid confusion, Afrikaans is often called Zuid-Afrikaans (South African) in Dutch.

Some Afrikaans sentences are exactly the same as in English, both in meaning and spelling. Only the way they are said is different.

- My pen was in my hand.

- My hand is in warm water.

Sample Text

Psalm 23 (1983 translation):

Die Here is my Herder, ek kom niks kort nie.

Hy laat my rus in groen weivelde. Hy bring my by waters waar daar vrede is.

Hy gee my nuwe krag. Hy lei my op die regte paaie tot eer van Sy naam.

Selfs al gaan ek deur donker dieptes, sal ek nie bang wees nie, want U is by my. In U hande is ek veilig.

Lord's Prayer (Afrikaans New Living translation)

Ons Vader in die hemel, laat U Naam geheilig word.

Laat U koningsheerskappy spoedig kom.

Laat U wil hier op aarde uitgevoer word soos in die hemel.

Gee ons die porsie brood wat ons vir vandag nodig het.

En vergeef ons ons sondeskuld soos ons ook óns skuldenaars vergewe het.

Bewaar ons sodat ons nie aan verleiding sal toegee nie; en bevry ons van die greep van die bose.

Want van U is die koninkryk,

en die krag,

en die heerlikheid,

tot in ewigheid.

Amen

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Afrikáans para niños

In Spanish: Afrikáans para niños