Taro facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Taro |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Alismatales |

| Family: | Araceae |

| Genus: | Colocasia |

| Species: |

C. esculenta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Colocasia esculenta |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

Taro (Colocasia esculenta) is a root vegetable that grows underground. It is the most common type of several plants in the Araceae family. People eat its starchy underground stem, called a corm, as well as its leaves and stems. Taro corms are a main food source in many parts of Africa, Oceania, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, much like yams. Many believe taro is one of the oldest plants ever grown by humans.

Contents

- What is Taro?

- Where Taro Grows

- Growing Taro

- Nutrition Facts

- How Taro is Used

- Images for kids

- See also

What is Taro?

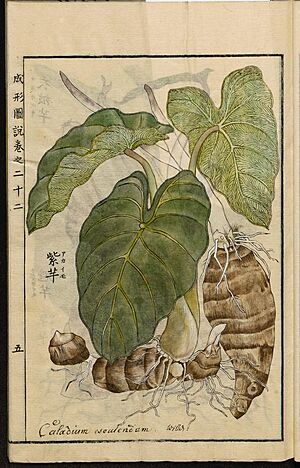

Taro is a perennial plant, meaning it lives for more than two years. It grows mainly in tropical areas. Its main part is the edible, starchy corm that grows underground. The plant has different shaped rhizomes (underground stems). Its leaves can be up to 40 by 25 centimetres (15+1⁄2 by 10 inches) in size. They are dark green on top and lighter green underneath. The leaf stems, called petioles, can grow up to .8–1.2 metres (2+1⁄2–4 feet) tall.

Similar Plants

Taro is related to plants like Xanthosoma and Caladium. These are often grown as decorative plants. People sometimes call them "elephant ear" plants because of their large leaves. Other similar taro types include giant taro (Alocasia macrorrhizos), swamp taro (Cyrtosperma merkusii), and arrowleaf elephant's ear (Xanthosoma sagittifolium).

What Does "Esculenta" Mean?

The second part of taro's scientific name, esculenta, comes from Latin. It simply means "edible."

Where Taro Grows

Scientists think Colocasia esculenta first grew in Southern India and Southeast Asia. But now, it grows naturally in many other places. It likely started in the Indomalayan realm, possibly in East India, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

From there, it spread. People took it eastward to Southeast Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific Islands. They also took it westward to Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean. Then, it moved south and west into East Africa and West Africa. From Africa, it traveled to the Caribbean and the Americas.

Taro was probably first found in the wet lowlands of Malaysia. There, it is called taloes.

In Australia, one type of taro is native to the Kimberley region. But the common type is now found everywhere and is seen as an invasive weed in some states.

In Europe, taro is grown in Cyprus. It's called Colocasi (Κολοκάσι in Greek) and has a special protected status. It also grows on the Greek island of Ikaria. People there say it was a very important food during World War II.

In Turkey, taro is known as gölevez. It is mainly grown on the Mediterranean coast.

In the southeastern United States, taro is considered an invasive species. You can often find it growing near ditches and bayous in places like Houston, Texas.

Growing Taro

A Look at Taro's History

Taro is one of the oldest crops grown by humans. It is found widely in tropical and subtropical areas of South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, northern Australia, and the Maldives. Taro plants can look very different from each other. This makes it hard to tell wild types from farmed ones.

Many believe taro was first grown in different places at different times. Some possible starting points include New Guinea, Mainland Southeast Asia, and northeastern India. However, newer studies suggest wild taro might have grown in many more places than thought before.

Archaeologists have found signs of taro use in many ancient sites. These include the Niah Caves in Borneo (about 10,000 years ago) and Kilu Cave in the Solomon Islands (28,000 to 20,000 years ago). At Kuk Swamp in New Guinea, there is evidence of farming from about 10,000 years ago.

Austronesian peoples carried taro to the Pacific Islands around 1300 BC. There, it became a main food for Polynesians. Taro was the most important of these root crops because it was less likely to have irritating crystals found in other plants. Taro was also a main food in Micronesia.

How Taro is Grown Today

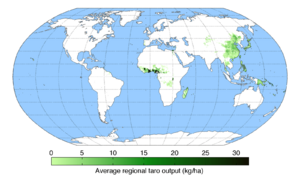

In 2022, the world produced 18 million tonnes of taro. Nigeria grew the most, making up 46% of the total.

Taro is the fifth most produced root and tuber crop worldwide. On average, about 7 tons of taro are grown per hectare.

Taro can grow in paddy fields where there is a lot of water. It can also grow in drier areas with rain or extra watering. Taro is one of the few crops that can grow in flooded conditions. Growing it in floods has benefits. It can produce more (about double) and grow when other crops are not in season. Flooding also helps control weeds.

| Taro production – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (Millions of tonnes) |

| 8.2 | |

| 1.9 | |

| 1.9 | |

| 1.7 | |

| 1.7 | |

| World | 17.7 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations | |

Like most root crops, taro grows well in deep, wet, or even swampy soils. It needs more than 2,500 mm (100 in) of rain each year. The plant is ready to harvest in six to twelve months in dry land. In wet land, it takes twelve to fifteen months. Farmers harvest taro when the plant gets shorter and its leaves turn yellow.

Nutrition Facts

Cooked taro is mostly water (64%) and carbohydrates (35%). It has very little protein or fat. A 100 grams (3.5 oz) serving of taro gives you 142 calories of food energy. It is a good source of vitamin B6, vitamin E, and manganese. It also has some phosphorus and potassium.

Raw taro leaves are mostly water (86%). They have some carbohydrates (7%), protein (5%), and fat (1%). The leaves are full of vitamins and minerals, especially vitamin K.

How Taro is Used

Cooking with Taro

Taro is a main food in African, Oceanic, and South Asian cultures. People usually eat its corm and leaves. The corms are often light purple from natural colors. They can be roasted, baked, or boiled. Taro has a sweet, nutty taste from its natural sugars. Its starch is easy to digest, so it is often used for baby food.

When raw, the taro plant is not safe to eat. It contains calcium oxalate, which has tiny needle-shaped crystals. These can cause an itchy feeling. But cooking or soaking taro in cold water overnight can remove the toxin. This makes it safe and tasty to eat.

Small, round taro corms are peeled and boiled. Then, they are sold frozen, in bags with their own liquid, or canned.

Taro in Oceania

Cook Islands

Taro is the most important crop in the Cook Islands. More land is used to grow taro than any other crop. It is a main food for the people there. Taro grows all over the country. How it is grown depends on the type of island. Taro is also important for the country's exports. The root is boiled, which is common in Polynesia. Taro leaves are also eaten. They are cooked with coconut milk, onion, and meat or fish.

Fiji

Taro (called dalo in Fijian) has been a main food in Fiji for hundreds of years. Its cultural importance is celebrated on Taro Day. Fiji started exporting taro in 1993. This happened after a plant disease hurt the taro industry in nearby Samoa. Fiji stepped in to supply taro to other countries. Almost 80% of Fiji's exported taro comes from Taveuni island. This is because a harmful taro beetle is not found there.

Hawaii

Kalo is the Hawaiian name for taro. This plant is very important in Hawaiian culture and mythology. Taro is a traditional staple in the native cuisine of Hawaii. People use taro to make poi, which is a thick paste. They also steam it and serve it like a potato, make taro chips, and use lūʻau leaves to make laulau (a dish wrapped in leaves).

In Hawaii, kalo is grown in dry fields or wet fields. Growing taro there can be hard because it needs fresh water. Kalo is usually grown in "pond fields" called loʻi. Some types of taro grown in dry fields are lehua maoli and bun long. Bun long is often used for taro chips. Dasheen is another dryland type.

The Hawaii Agricultural Statistics Service found that taro production has gone down. This is due to city growth, pests, and diseases. A non-native apple snail and a plant rot disease are big problems. Even though pesticides could help, they are not allowed in loʻi fields. This is to stop chemicals from getting into streams and the ocean.

Taro's Social Role in Hawaii

Important parts of Hawaiian culture are about kalo. For example, the name for a traditional Hawaiian feast, the lūʻau, comes from kalo. Young kalo tops cooked with coconut milk and chicken or octopus are often served at luaus.

In ancient Hawaiian custom, people were not allowed to fight when a bowl of poi was "open." It was also rude to fight in front of an elder. People should not raise their voice or make angry comments.

What is a Loʻi?

A loʻi is a wet field used to grow kalo. Hawaiians have traditionally used irrigation to grow kalo. Wet fields often produce more kalo than dry fields. Kalo grown in wet fields needs a steady flow of water.

About 300 types of kalo were first brought to Hawaiʻi. About 100 types still exist. The kalo plant takes seven months to grow until harvest. So, loʻi fields are used in turns. This allows the soil to get nutrients back. Stems are usually replanted in the loʻi for future harvests.

Hawaiian History and Taro

One Hawaiian story says the taro plant is an ancestor to Hawaiians. The legend tells of two important siblings: Papahānaumoku (Earth mother) and Wākea (Sky father). They created the islands of Hawaii and a beautiful woman, Hoʻohokukalani.

Papua New Guinea

The taro corm is a traditional staple crop for many people in Papua New Guinea. It is traded to areas where it does not grow. Taro from some regions is very well-liked. For example, Lae taro is highly valued.

Among the Urapmin people of Papua New Guinea, taro (called ima in Urap) is the main food. It is eaten along with sweet potato. In fact, the Urap word for "food" combines these two words.

Polynesia

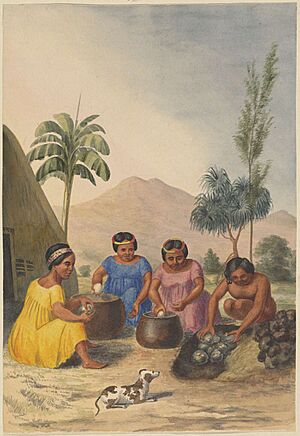

Taro is seen as the main starch in traditional Polynesian cooking. It is a common and respected food. Prehistoric sailors from Southeast Asia first brought it to the Polynesian islands. The taro root is cooked in many ways. These include baking, steaming in earth ovens (umu or imu), boiling, and frying. The famous Hawaiian food poi is made by mashing steamed taro roots with water.

Taro is also used in traditional desserts. Samoan fa'ausi is made from grated, cooked taro mixed with coconut milk and brown sugar. The leaves of the taro plant are also important in Polynesian cooking. They are used as edible wrappers for dishes. Examples include Hawaiian laulau, Fijian and Samoan palusami (wrapped around onions and coconut milk), and Tongan lupulu (wrapped corned beef).

The Hawaiian laulau traditionally has pork, fish, and lu'au (cooked taro leaf). The wrapping is made of inedible ti leaves. Cooked taro leaf feels like cooked spinach. So, it is not used as a wrapper itself.

Samoa

In Samoa, young taro leaves and coconut milk are wrapped into bundles. These are cooked with other food in an earth oven. These bundles are called palusami or lu'au. They taste smoky, sweet, and savory, with a unique creamy texture. The root is also baked (Talo tao) in the umu or boiled with coconut cream (Faálifu Talo). It has a slightly plain and starchy taste. Some people call it the Polynesian potato.

Tonga

Lū is the Tongan word for the edible leaves of the taro plant (called talo in Tonga). It is also the name of a traditional dish made with them. This meal is still made for special events and especially on Sundays. The dish has chopped meat, onions, and coconut milk. These are wrapped in taro leaves (lū talo). Then, it is wrapped in a banana leaf (or aluminum foil today) and cooked in the ʻumu. There are different types of lū depending on the filling:

- Lū pulu – lū with beef, often using imported corned beef

- Lū sipi – lū with lamb

- Lū moa – lū with chicken

- Lū hoosi – lū with horse meat

Taro on Oceanian Atolls Islands on the edge of Oceania (like Tuvalu, Tokelau, and Kiribati) are often atolls. These islands have poor soil. So, taro was not a traditional food. Today, it is a main food because it is brought in from other islands. The traditional main food was Swamp Taro, called Pulaka or Babai. It is related to taro but takes a very long time to grow (3–5 years). It has bigger, denser corms and rougher leaves. It is grown in special pits dug down to the freshwater. Because it takes so long to grow, it is usually eaten during celebrations. It can also be dried and stored for later.

Taro in East Asia

China

Taro (simplified Chinese: 芋头; traditional Chinese: 芋頭; pinyin: yùtou; Cantonese Yale: wuhtáu) is often used as a main dish in Chinese cuisine. It can be steamed with or without sugar. It can also replace other cereals. People steam, boil, or stir-fry it. It is also used to add flavor to dishes. In Northern China, it is often boiled or steamed, then peeled and eaten like a potato. It is commonly cooked with pork or beef.

In Cantonese dim sum, taro is used to make a small dish called taro dumpling. It is also used in a pan-fried dish called taro cake. Taro can be shredded into long strips and woven to form a seafood birdsnest. In Fujian cuisine, it is steamed or boiled and mixed with starch to make a dough for dumplings.

Taro cake is a special food eaten during Chinese New Year celebrations. For dessert, taro can be mashed into a purée. It is also used as a flavor in tong sui (sweet soups), ice cream, and other desserts like Sweet Taro Pie. McDonald's even sells taro-flavored pies in China.

Taro paste, a traditional Cantonese dessert, comes from the Chaoshan region of China. It is made mostly from taro. The taro is steamed and mashed into a thick paste. Then, lard or fried onion oil is added for smell. It is usually sweetened with water chestnut syrup and served with ginkgo nuts. Newer versions add coconut cream and sweet corn. This dessert is often served as the last course at traditional Teochew wedding dinners.

Japan

A similar plant in Japan is called satoimo (satoimo (里芋), meaning "village potato"). The smaller corms that grow from the main satoimo are called koimo (child corms) and magoimo (grandchild corms). Satoimo has been grown in Southeast Asia since the late Jōmon period. It was a main food before rice became more common. The satoimo tuber is often cooked by simmering it in fish stock (dashi) and soy sauce. The stalk, zuiki (zuiki), can also be prepared in different ways.

Korea

In Korea, taro is called toran (Korean: 토란: "earth egg"). The corm is stewed, and the leaf stem is stir-fried. Taro roots can be used as medicine, especially for insect bites. It is made into the Korean soup toranguk (토란국). Taro stems are often used in a spicy beef soup called yukgaejang (육개장).

Taiwan

In Taiwan, taro—yùtóu (芋頭) in Mandarin, and ō͘-á (芋仔) in Taiwanese—grows well. It can grow almost anywhere with little care. Before the Taiwan Miracle made rice cheap for everyone, taro was a main food in Taiwan. Today, taro is used more often in desserts. Taro chips are a popular snack, like potato chips. They are harder and have a nuttier taste. Another popular Taiwanese snack is taro ball, served on ice or deep-fried. Taro is a common flavor in desserts and drinks, such as bubble tea.

Taro in Southeast Asia

Indonesia

In Indonesia, taro is widely used for snacks, cakes, crackers, and even macarons. So, you can find it everywhere. Some types are grown for special traditions. Taro is usually known as "keladi," but other types are called "talas." The vegetable soups, sayur asem and sayur lodeh, may use taro and its leaves. They also use lompong (taro stem) in Java. Chinese people in Indonesia often eat taro with stewed rice and dried shrimp. The taro is cut into cubes and cooked with rice, shrimp, and sesame oil. In New Guinea of Indonesia, there are traditional dishes made from taro and its leaves. These include keripik keladi (sweet spicy taro chips), keladi tumbuk (pounded taro with vegetables), and aunu senebre (anchovies mixed with taro leaf slices). Mentawai people have a traditional food called lotlot, which is taro leaves cooked with smoked fish.

Philippines

In the Philippines, taro is usually called gabi, abi, or avi. It is found all over the islands. Because it can grow in wet and swampy areas, it is one of the most common vegetables. The leaves, stems, and corms are all eaten. A popular taro recipe is laing from the Bicol Region. This dish uses taro leaves (and sometimes stems) cooked in coconut milk. It is seasoned with fermented shrimp or fish paste. Sometimes, it is made very spicy with red chilies. Taro is also used in the Philippine national stew, sinigang. This stew is made with pork, beef, shrimp, or fish, and a souring agent. Peeled and diced taro corms are added to make it thicker. The corm is also a basic ingredient for ginataan, a coconut milk and taro dessert.

Thailand

In Thai cuisine, taro Thai: เผือก (pheuak) is used in many ways. Boiled taro is sold in markets, already peeled and diced, as a snack. Boiled taro pieces with coconut milk are a traditional Thai dessert. Raw taro is also often sliced and deep-fried to make chips (เผือกทอด). Like in other Asian countries, taro is a popular flavor for ice cream in Thailand.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, there are many types of taro plants. One is called khoai môn. It is used as a filling in spring rolls, cakes, puddings, and sweet soup desserts, smoothies, and other desserts. Taro is used in the Tết dessert chè khoai môn, which is sticky rice pudding with taro roots. The stems are also used in soups like canh chua. Another type is called khoai sọ, which is smaller than khoai môn.

Another common taro plant grows roots in shallow water. Its stems and leaves grow above the water. This taro plant has substances that can make your mouth and throat feel hot and itchy. Farmers in the north used to grow them to cook the stems and leaves for their pigs. They grew back quickly from their roots. After cooking, the itchy substance in the soup was reduced, so the pigs could eat it. Today, this practice is not as common in Vietnam. These taro plants are often called khoai ngứa, which means "itchy potato."

Taro in South Asia

Taro roots are commonly known as Arbi or Arvi in Urdu and Hindi languages. It is a common dish in Northern India and Pakistan. Arbi Gosht (meat) Masala Recipe is a tangy mutton curry with taro. Mutton and Arbi are cooked with whole spices and tomatoes, which gives the dish a wonderful taste.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, taro is a very popular vegetable called kochu (কচু) or mukhi (মুখি). In the Sylheti language, it is called mukhi. It is usually cooked into a curry with small prawns or ilish fish. Some dishes are cooked with dried fish. Its green leaves, kochu pata (কচু পাতা), and stem, kochu (কচু), are also eaten. They are usually ground into a paste or finely chopped to make shak. But they must be boiled well first. Taro stolons or stems, kochur loti (কচুর লতি), are also liked by Bangladeshis. They are cooked with shrimp, dried fish, or the head of the ilish fish. Taro is available, fresh or frozen, in the UK and US in most Asian stores. Another type called maan kochu is eaten. It is rich in vitamins and nutrients. Maan Kochu is made into a paste and fried to make a food called Kochu Bata.

India

In India, taro or eddoe is a common dish served in many ways.

In Gujarat, it is called Patar Vel or Saryia Na Paan. Green leaves are used to make a roll. A paste of gram flour, salt, turmeric, and red chili powder is put inside the leaves. Then, it is steamed and cut into small pieces. It can also be deep-fried.

In Mizoram, in north-eastern India, it is called bäl. The leaves, stalks, and corms are eaten as dawl bai. The leaves and stalks are often dried and saved to be eaten in the dry season.

In Assam, taro is known as kosu (কচু). Different parts of the plant are used to make dishes. The leaf buds, called kosu loti (কচু লতি), are cooked with sour dried fruits or tamarind. Similar dishes are made from the long root-like structures called kosu thuri. A sour fried dish is made from its flower (kosu kala). Porridges are made from the corms. They can also be boiled, seasoned with salt, and eaten as snacks.

In Manipur, taro is known as pan. The Kukis call it bal. Boiled bal is a snack eaten with chutney or chili flakes. It is also cooked as a main dish with smoked or dried meat, beans, and mustard leaves. Sun-dried taro leaves are used later in broths and stews. It is widely available and eaten in many forms. It can be baked, boiled, or cooked into a curry with hilsa fish or fermented soybeans. The leaves are also used in a special dish called utti, cooked with peas.

It is called arbi in Urdu/Hindi and arvi in Punjabi in north India. In Sanskrit, it is called kəchu (कचु).

In Himachal Pradesh, in northern India, taro corms are called ghandyali. The plant is known as kachalu. A dish called patrodu is made using taro leaves rolled with corn or gram flour and boiled. Another dish, pujji, is made with mashed leaves and the plant's trunk. Ghandyali or taro corms are prepared as a separate dish. In Shimla, a pancake-style dish, called patra or patid, is made using gram flour.

In Uttarakhand and Nepal, taro is seen as a healthy food and cooked in many ways. The special gaderi (taro type) from Kumaon is very popular. Most often, it is boiled in tamarind water until soft. Then, it is cut into cubes and stir-fried in mustard oil with fenugreek leaves. Another way to cook it is to boil it in salt water until it becomes a porridge. The young leaves, called gaaba, are steamed, sun-dried, and stored. Taro leaves and stems are pickled. Crushed leaves and stems are mixed with black lentils and dried into small balls called badi. These stems can also be sun-dried and stored. On special days, women worship "seven sages" and only eat rice with taro leaves.

In Maharashtra, in western India, the leaves, called alu che paana, are prepared. They are de-veined and rolled with a paste of gram flour. Then, they are seasoned with tamarind paste, red chili powder, turmeric, coriander, and salt, and finally steamed. These can be eaten whole, cut into pieces, or shallow-fried as a snack called alu chi wadi. Alu chya panan chi patal bhaji, a lentil and colocasia leaves curry, is also popular. In Goan and Konkani cuisine, taro leaves are very popular. A tall-growing type of taro is used on the western coast of India to make patrode, patrade, or patrada (meaning "leaf-pancake"). This dish uses gram flour, tamarind, and other spices.

In Gujarat, it is called patar vel or saryia na paan. Gram flour, salt, turmeric, and red chili powder are made into a paste and stuffed inside a roll of green taro leaves. Then, it is steamed and cut into small portions, and then fried.

Sindhis call it kachaloo. They fry it, press it, and re-fry it to make a dish called tuk. This dish goes well with Sindhi curry.

In Kerala, a state in southern India, taro corms are called chembu kizhangu (ചേമ്പ് കിഴങ്ങ്). They are a staple food, a side dish, and an ingredient in dishes like sambar. As a main food, it is steamed and eaten with a spicy chutney made of green chilies, tamarind, and shallots. The leaves and stems of some taro types are also used as a vegetable in Kerala. In Dakshin Kannada in Karnataka, it is used as a breakfast dish, either made like fritters or steamed.

In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, taro corms are called sivapan-kizhangu (seppankilangu or cheppankilangu), chamagadda, or chaama dumpa. They can be prepared in many ways. For example, steamed and sliced corms can be deep-fried in oil to make chamadumpa chips, eaten with rice. Or, they can be cooked in a tangy tamarind sauce with spices, onion, and tomato.

In the east Indian state of West Bengal, taro corms are thinly sliced and fried to make chips called kochu bhaja(কচু ভাজা). The stem is used to cook kochur saag (কচুর শাগ) with fried hilsha (ilish) fish head or boiled chickpeas. This is often eaten as a starter with hot rice. The corms are also made into a paste with spices and eaten with rice. A popular dish is a spicy curry made with prawn and taro corms. Gathi kochu (গাঠি কচু) (a taro type) is very popular and used to make a thick curry called gathi kochur dal (গাঠি কচুর ডাল). Here, kochur loti (কচুর লতি) (taro stolon) dry curry is a popular dish. It is usually made with poppy seeds and mustard paste. Leaves and corms of shola kochu (শলা কচু) and maan kochu (মান কচু) are also used to make popular traditional dishes.

In Mithila, Bihar, taro corms are called ədua (अडुआ). Its leaves are called ədikunch ke paat (अड़िकंच के पात). A curry of taro leaves is made with mustard paste and sour sun-dried mango pulp.

In Odisha, taro corms are called saru. Dishes made of taro include saru besara (taro in mustard and garlic paste). It is also a key ingredient in dalma, an Odia cuisine staple (vegetables cooked with dal). Sliced taro corms, deep-fried in oil and mixed with red chili powder and salt, are called saru chips.

Maldives

Ala was widely grown in the southern atolls of Addu Atoll, Fuvahmulah, Huvadhu Atoll, and Laamu Atoll. It is still considered a staple even after rice was brought in. Ala and olhu ala are still widely eaten all over the Maldives. They are cooked or steamed with salt and eaten with grated coconut, chili paste, and fish soup. It is also made into a curry. The corms are sliced and fried to make chips. They are also used to make different sweets.

Nepal

Taro grows in the Terai and hilly regions of Nepal. The root (corm) of taro is called pindalu (पिँडालु). The petioles with leaves are called karkalo (कर्कलो), Gava (गाभा), and also Kaichu (केेेैचु) in Maithili. Almost all parts are eaten in different dishes. Boiled taro corm is commonly served with salt, spices, and chilies. Taro is a popular dish in the hilly region. Chopped leaves and petioles are mixed with Urad bean flour to make dried balls called maseura (मस्यौरा). Large taro leaves are used as a natural umbrella when it rains. Taro has been popular for a long time, and this is shown in songs and textbooks. For example, "Our life is as vulnerable as water stuck in the leaf of taro."

Taro is grown and eaten by the Tharu people in the Inner Terai. Roots are mixed with dried fish and turmeric. Then, they are dried into cakes called sidhara. These are cooked in a curry with radish, chili, garlic, and other spices to eat with rice. The Tharu prepare the leaves in a fried vegetable side-dish, which is also found in Maithili cooking.

Pakistan

In Pakistan, taro or eddoe or arvi is a very common dish. It is served with or without gravy. A popular dish is arvi gosht, which includes beef, lamb, or mutton. The leaves are rolled with gram flour batter and then fried or steamed to make a dish called Pakora. This is finished by adding red chilies and carrom seeds. Taro or arvi is also cooked with chopped spinach. The dish called Arvi Palak is another well-known dish made of Taro.

Sri Lanka

Many types of taro are found in Sri Lanka. Several are edible, but most are not safe for humans to eat. Edible types (like kiri ala, kolakana ala, gahala, and sevel ala) are grown for their corms and leaves. Sri Lankans eat corms after boiling them or making them into a curry with coconut milk. Some types of leaves are also eaten.

Taro in the Middle East and Europe

Ancient Romans ate taro much like we eat potatoes today. They called this root vegetable colocasia. The Roman cookbook Apicius describes ways to prepare taro. These include boiling it, cooking it with sauces, and serving it with meat or fowl. After the Roman Empire fell, taro was used less in Europe. This was because trade with Egypt, which Rome used to control, decreased. When the Spanish and Portuguese sailed to the new world, they brought taro with them. Recently, people have become more interested in unique foods, and taro use is growing.

Cyprus

In Cyprus, taro has been used since the time of the Roman Empire. Today, it is known as kolokas in Turkish or kolokasi (κολοκάσι) in Greek. This name comes from the Ancient Greek name for lotus root. It is usually stir-fried with celery and onion with pork, chicken, or lamb, in a tomato sauce. A version without meat is also made. The small corms are called poulles. They are first stir-fried, then cooked with dry red wine and coriander seeds. Finally, they are served with fresh lemon juice.

Greece

In Greece, taro grows on Icaria. People from Icaria say taro saved them from hunger during World War II. They boil it until soft and serve it as a salad.

Lebanon

In Lebanon, taro is known as kilkass. It is grown mainly along the Mediterranean coast. The leaves and stems are not eaten in Lebanon. The type grown there produces round to slightly oval tubers. They range in size from a tennis ball to a small cantaloupe. Kilkass is a popular winter dish in Lebanon. It is prepared in two ways: kilkass with lentils is a stew flavored with crushed garlic and lemon juice. Another way is ’il’as (Lebanese pronunciation of قلقاس) bi-tahini. Another common way to prepare taro is to boil it, peel it, then slice it into 1 cm (0.39 in) thick pieces. These are then fried and soaked in edible "red" sumac.

In northern Lebanon, it is called a potato with the name borshoushi. It is also prepared as part of a lentil soup with crushed garlic and lemon juice. Also in the north, it is known as bouzmet, mainly around Menieh. There, it is first peeled and left to dry in the sun for a few days. After that, it is stir-fried in a lot of vegetable oil in a pot until golden brown. Then, a lot of cut, melted onions are added, along with water, chickpeas, and some seasoning. These are left to cook slowly for a few hours, making a stew-like dish. It is seen as a difficult dish to make. This is because of the careful preparation and the texture and taste the taro must reach. The smaller type of taro is more popular in the north because it is more tender.

Portugal

In the Azores, taro is known as inhame or inhame-coco. It is commonly steamed with potatoes, vegetables, and meats or fish. The leaves are sometimes cooked into soups and stews. It is also eaten as a dessert. First, it is steamed and peeled. Then, it is fried in vegetable oil or lard, and finally sprinkled with sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Taro grows a lot in the rich land of the Azores and in streams fed by mineral springs. Because people from the Azores have moved to other countries, inhame is also found in those places.

Turkey

Taro (Turkish: gölevez) is grown on the south coast of Turkey, especially in Mersin, Bozyazı, Anamur, and Antalya. It is boiled in a tomato sauce or cooked with meat, beans, and chickpeas. It is often used instead of potatoes.

Taro in Africa

Egypt

In Egypt, taro is known as qolqas (Egyptian Arabic: قلقاس). The corms are larger than those found in North American supermarkets. After being peeled, it is cooked in one of two ways: cut into small cubes and cooked in broth with fresh coriander and chard. This is served with meat stew. Or, it is sliced and cooked with minced meat and tomato sauce.

Canary Islands

Taro has stayed popular in the Canary Islands. There, it is known as ñame. It is often used in thick vegetable stews, like potaje de berros (cress potage). Or, it is simply boiled and seasoned with mojo sauce or honey. In Canarian Spanish, the word Ñame means Taro. In other Spanish dialects, it usually means yams.

East Africa

In Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, taro is commonly known as arrow root, yam, amayuni (plural) or ejjuni (singular), ggobe, or nduma and madhumbe in some local Bantu languages. There are several types, and each has its own local name. It is usually boiled and eaten with tea or other drinks, or as the main starch of a meal. It is also grown in Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe.

South Africa

It is known as amadumbe (plural) or idumbe (singular) in the Zulu language of Southern Africa.

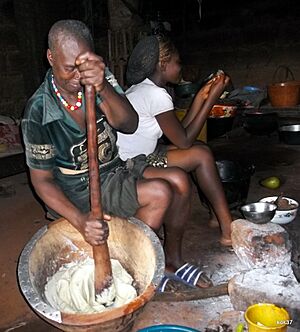

West Africa

Taro is a staple crop in West Africa, especially in Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. It is called cocoyam in Nigeria, Ghana, and English-speaking Cameroon. It is called macabo in French-speaking Cameroon. In Democratic Republic of Congo or Republic of Congo, it is mbálá ya makoko. It is mankani in Hausa language, koko and lambo in Yoruba, and ede in Igbo language. Cocoyam is often boiled, fried, or roasted and eaten with a sauce. In Ghana, it can replace plantain in making fufu when plantains are not in season. It is also cut into small pieces to make a soupy baby food and appetizer called mpotompoto. It is common in Ghana to find cocoyam chips (deep-fried slices). Cocoyam leaves, called kontomire in Ghana, are a popular vegetable for local sauces like palaver sauce and egusi/agushi stew. It is also commonly eaten in Guinea and parts of Senegal, as a leaf sauce or a vegetable side. It is called jaabere in the local Pulaar dialect.

Taro in the Americas

Brazil

In Portuguese-speaking countries, inhame (pronounced or literally "yam") and cará are common names for different plants. These plants have edible parts from the genera Alocasia, Colocasia (family Araceae) and Dioscorea (family Dioscoreaceae). The edible parts are usually tubers. The only exception is Dioscorea bulbifera, called cará-moela (meaning "gizzard yam") in Brazil, which is never called an inhame. What is called an inhame or a cará changes by region. But in Brazil, carás are shaped like potatoes, while inhames are longer.

In the Brazilian Portuguese of the hotter and drier Northeastern region, both inhames and carás are called batata (meaning "potato"). To tell them apart, potatoes are called batata-inglesa (meaning "English potato"). This name is used in other regions to tell it apart from batata-doce, "sweet potato". This is a bit funny because both were first grown by native peoples of South America, their home continent. They were only later brought to Europe by explorers.

Taros are often prepared like potatoes. They are eaten boiled, stewed, or mashed. Usually, they are seasoned with salt and sometimes garlic. They are eaten as part of a meal, most often lunch or dinner.

Central America

In Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama, taro is eaten in soups. It is used instead of potatoes and made into chips. It is known locally as malanga (also malanga coco), a word from the Bantu language. It is called dasheen in Belize and Costa Rica, quiquizque in Nicaragua, and otoe in Panama.

Haiti

In Haiti, it is usually called malanga or taro. The corm is grated into a paste and deep-fried to make a fritter called Acra. Acra is a very popular street food in Haiti.

Jamaica

In Jamaica, taro is known as coco, cocoyam, and dasheen. Corms that are white all the way through are called minty-coco. The leaves are also used to make Pepper Pot Soup, which may include callaloo.

Suriname

In Suriname, it is called tayer, taya, pomtayer, or pongtaya. The taro root is called aroei by the native Surinamese people. It is commonly known as "Chinese tayer." The type known as eddoe is also called Chinese tayer. It is a popular crop among the Maroon people in the interior. This is because it is not harmed by high water levels. The dasheen type, often planted in swamps, is rare, but people like its taste. The closely related Xanthosoma species is the base for the popular Surinamese dish pom. The cooked taro leaf (taya-wiri, or tayerblad) is also a well-known green leafy vegetable.

Trinidad and Tobago

In Trinidad and Tobago, it is called dasheen. The leaves of the taro plant are used to make the Trinidadian version of the Caribbean dish called callaloo. This dish is made with okra, dasheen/taro leaves, coconut milk or cream, and herbs. It is served as a side dish, similar to creamed spinach. Callaloo is sometimes made with crab legs, pumpkin, and okra. It is usually served with rice or made into a soup with other roots. The leaves are also stir-fried with onions, hot pepper, and garlic until they are soft. This dish is called "bhaji." It is popular with Indo-Trinidadian people. The leaves are also fried in a split pea batter to make "saheena," a fritter from India.

United States

Taro has been grown in the United States for hundreds of years. William Bartram saw people on the South Carolina Sea Islands eating roasted taro roots, which they called tanya, in 1791. By the 1800s, it was a common food crop from Charleston to Louisiana.

In the 1920s, dasheen, as it was known, was highly praised by the Secretary of the Florida Department of Agriculture. He said it was a valuable crop to grow in wet fields. Fellsmere, Florida, was seen as a perfect farming area for dasheen. It was used instead of potatoes and dried to make flour. Dasheen flour was said to make great pancakes when mixed with wheat flour.

Poi is a Hawaiian cuisine staple food made from taro. Traditional poi is made by mashing cooked taro on a wooden board with a carved pestle. Modern ways use a machine to make large amounts for stores. Water is added to the paste to make it the right thickness. In Hawaii, this is called "one-finger," "two-finger," or "three-finger" poi. This refers to how many fingers you need to scoop it up (thicker poi needs fewer fingers).

Since the late 1900s, taro chips have been sold in many supermarkets and health food stores. Taro is also often used in American Chinatowns in Chinese cuisine.

Venezuela

In Venezuela, taro is called ocumo chino or chino. It is used in soups and sancochos (stews). Soups have large pieces of different tubers, including ocumo chino. This is especially true in the eastern part of the country, where there is influence from the West Indies. It is also used with meats in parrillas (barbecues) or fried fish when yuca is not available. Ocumo is a native name. Chino means "Chinese," which is an adjective for foods that are seen as exotic. Ocumo without "chino" is a tuber from the same plant family, but it does not have taro's purplish color inside. Ocumo is the Venezuelan name for malanga, so ocumo chino means "Chinese malanga." Taro is always prepared boiled. No porridge form is known in the local cooking.

West Indies

Taro is called dasheen in the English-speaking countries of the West Indies. Smaller types of corms are called eddo or tanya. Taro is grown and eaten as a main crop in the region. There are differences among these roots. Taro or dasheen is mostly blue when cooked. Tanya is white and very dry. Eddoes are small and very slimy.

In the Spanish-speaking countries of the Spanish West Indies, taro is called ñame. The Portuguese version (inhame) is used in former Portuguese colonies where taro is still grown, like the Azores and Brazil. In Puerto Rico and Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, it is sometimes called malanga or yautia. In some countries, like Trinidad and Tobago, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Dominica, the leaves and stem of the dasheen, or taro, are often cooked and blended into a thick liquid called callaloo. This is served as a side dish similar to creamed spinach. Callaloo is sometimes made with crab legs, coconut milk, pumpkin, and okra. It is usually served with rice or made into a soup with other roots.

Taro as an Ornamental Plant

Taro is also sold as a decorative plant. It is often called elephant ears because of its large leaves. It can be grown indoors or outdoors if there is a lot of moisture in the air. In the UK, it has won a special award for garden plants.

Taro in Science

Taro is used in science experiments to study plant colors, especially how much red and purple color is on the top and bottom of its leaves. A recent study found tiny honeycomb-like structures on the taro leaf. These structures make the leaves super water-repellent. Water drops form a high angle on the leaf, around 148 degrees, meaning they roll right off.

In an article by Melissa K. Nelson, it was mentioned that scientists at the University of Hawaii tried to get patents and change taro genetically. But activists and farmers convinced them not to. In 2006, the University of Hawaii gave up its patents on three types of Hawaiian taro. They also agreed to stop genetically changing Hawaiian taro. However, researchers continue to try to change a Chinese type of taro.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Taro para niños

In Spanish: Taro para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |