Native cuisine of Hawaii facts for kids

Native Hawaiian cuisine is all about the traditional foods eaten in Hawaiʻi long before people from Europe and Asia arrived. This food culture used plants and animals found on the islands, plus others brought by the first Polynesian travelers. These travelers became the Native Hawaiians.

Contents

History of Hawaiian Food

Early Travelers and Their "Canoe Foods"

The first Polynesian sailors likely arrived in the Hawaiian Islands between 300 and 500 AD. When they got there, Hawaiʻi didn't have many edible plants. But there was plenty of fish, shellfish, and seaweed. They also found birds that couldn't fly, which were easy to catch, and their eggs.

These brave voyagers brought many important food plants with them. Experts believe they introduced about 27 to 30 different plants. The most important was taro. For hundreds of years, taro—and the poi made from it—was the main food for Hawaiians. It's still very popular today!

They also planted ʻuala (sweet potatoes) and yams. Later settlers brought ʻulu (breadfruit) and baking bananas. Coconuts and sugarcane also came with these early travelers.

The ancient Polynesians also brought pigs, chickens, and dogs on their long canoe trips. These animals became important food sources. Pigs were sometimes used in religious ceremonies, with some meat eaten by priests and the rest shared in big celebrations. The early Hawaiian diet was very varied, including many types of seafood and sweet potatoes. Sadly, some bird species were eaten so much that they became extinct.

Ahupua'a: Land for Everyone

In ancient Hawaiʻi, communities divided their land into sections called Ahupuaʻa. These sections usually stretched from the top of a mountain all the way to the ocean. This smart way of dividing land meant that each community had access to all the natural resources they needed. They could be mostly self-sufficient.

Importantly, these land divisions gave communities access to streams. These streams flowed from the valleys down to the ocean. This allowed them to build loʻi, which were irrigated mud patches used for growing kalo (taro). Where the streams met the ocean, people also created fish ponds to raise seafood.

Food Traditions and Culture

ʻAwa (Piper methysticum, also known as kava) was a traditional drink for Hawaiians. Certain foods like breadfruit, sweet potato, kava, and heʻe (octopus) were connected to the four main Hawaiian gods: Kāne, Kū, Lono, and Kanaloa.

Popular seasonings included paʻakai (salt), ground kukui nut, limu (seaweed), and ko (sugarcane). Sugarcane was used for sweetness and as medicine.

In ancient times, there were strict rules about food. Men did all the cooking, and food for women was cooked in a separate imu (underground oven). Men and women also ate their meals separately. This rule, called kapu, ended in 1819. The old way of cooking with an imu is still used today for special events and is popular with visitors.

The wood from the Thespesia populnea tree was used to make food bowls.

Hawaiians feel a strong connection to kalo (taro). The Hawaiian word for family, ʻohana, comes from ʻohā, which means the shoot that grows from the taro plant. Just as new shoots grow from the taro, people grow from their family. This is why sharing a bowl of poi means no fighting.

Main Ingredients

Everyday Foods

- Kalo (Taro): This was the most important food in the Native Hawaiian diet. Taro plants were grown in loʻi kalo, which are terraced mud patches often watered by springs or streams. Taro tubers were usually steamed and eaten in chunks, or pounded into paʻiai or poi. The leaves were also used to wrap other foods for steaming.

- `Uala (Sweet potato): This was another common crop brought by the first Polynesians. Sweet potatoes needed less water than taro, so they were important in drier areas. Sweet potatoes could be cooked like taro, by steaming, boiling, or baking in an imu.

- `Ulu (Breadfruit): This was the third main crop brought by Polynesians. Breadfruit grows on trees, unlike taro and sweet potatoes which grow in the ground. Having different types of crops helped Hawaiians have food even when seasons changed. Breadfruit is starchy and can be prepared like sweet potatoes and taro.

- Iʻa (fish) and other seafood: Foods like Opihi (limpets) and Wana (sea urchin) were a big part of the Hawaiian diet. The reefs around the islands provided lots of food. Seafood was often eaten raw, seasoned with sea salt and limu (seaweed). This way of preparing fish led to the popular dish called poke.

- Hāpuʻu ʻiʻi (Hawaiian tree fern): This plant is native to Hawaiʻi and was not brought by the Polynesians. Its young, coiled fronds (called fiddles) were eaten boiled. The starchy center of the fern trunk was sometimes eaten during times of food shortage or used as pig feed.

Special Foods for Celebrations

Some foods were mainly eaten by royalty and important people, but sometimes common people enjoyed them too. These included Puaʻa (pig), Moa (chicken), and `Ilio (dog). These animals were brought to Hawaiʻi by the Polynesians, as there were no large mammals before them. Pigs were hunted, while chickens and dogs were raised at home. These animals were usually slow-cooked in an imu, an underground oven. They were also cooked by stuffing them with hot rocks and wrapping them in leaves.

Dishes and How They Were Made

Most cooked foods in Native Hawaiian cuisine were steamed, boiled, or slow-cooked in underground ovens called imu. Since they didn't have fireproof pots, they heated rocks in fires and put the hot rocks into bowls of water to boil or steam food. Many other foods, like fruits and most seafood, were eaten raw.

Here are some traditional Hawaiian dishes:

- Kalua: This is pig cooked underground in an imu.

- Poi: Made from cooked, mashed, and sometimes slightly fermented taro. It's the main starchy food in the Hawaiian diet.

- Laulau: Made with beef, pork, or chicken and salted butterfish. These are wrapped in taro leaves and then ti leaves. Traditionally, it was cooked in an imu.

- Poke: This is a raw, marinated fish or seafood salad (like ahi poke or octopus poke). It's made with sea salt, seaweed, kukui nut oil, and sometimes soy sauce and sesame oil today.

- Lūʻau: This dish is made by cooking coconut milk with taro leaves in a pot. It has a creamy texture. Squid is often cooked with it, but chicken can be used instead.

- Haupia: A dessert similar to flan, made with coconut milk and ground arrowroot. Today, cornstarch is often used instead of arrowroot.

- Koʻele palau: A dessert made from cooked sweet potato mashed and mixed with coconut milk.

- Inamona: A traditional relish or condiment often eaten with meals. It's made from roasted and mashed kukui nutmeats and sea salt. Sometimes, it's mixed with edible seaweed.

- Kulolo: A pudding dessert made from grated taro corm and coconut milk. It's baked in an imu and has a fudge-like texture.

- Piele: Another Hawaiian pudding, similar to Kulolo, but made with grated sweet potato or breadfruit mixed with coconut cream and baked.

Festivals and Special Occasions

For important events, a traditional feast called an ʻahaʻaina was held. For example, when a woman was going to have her first child, her husband would start raising a pig for the ʻahaʻaina mawaewae feast. This feast celebrated the birth of a child. Besides pig, other foods like mullet, shrimp, crab, seaweed, and taro leaves were needed for the feast.

The word lūʻau, which is used today for such feasts, didn't become common until 1856. It replaced the older Hawaiian words ʻahaʻaina and pāʻina. The name lūʻau came from a dish always served at these feasts: young taro tops baked with coconut milk and chicken or octopus.

Meat was often cooked by flattening the whole animal and grilling it over hot coals, or by putting it on sticks over a fire. Larger meats like fowl, pigs, and dogs were usually cooked in earth ovens, or roasted over a fire during special feasts.

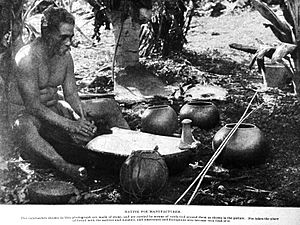

Hawaiian earth ovens, called an imu, cook food by both roasting and steaming. This method is called kālua. A pit is dug in the ground and lined with volcanic rocks or other rocks that won't break when heated. A fire is built with embers. When the rocks are glowing hot, the embers are removed. Foods wrapped in ti, ginger, or banana leaves are placed in the pit. Then, they are covered with wet leaves, mats, and a layer of earth. Sometimes, water is added through a bamboo tube to create steam.

The strong heat from the hot rocks cooked food thoroughly. People could cook enough food for several days at once. They would take out what they needed and put the cover back to keep the rest warm. Sweet potatoes, taro, breadfruit, and other vegetables were cooked in the imu, as well as fish. Saltwater eel was salted and dried before being put into the imu. Chickens, pigs, and dogs were cooked in the imu with hot rocks placed inside their bodies.

Paʻina is the Hawaiian word for a meal, and it can also mean a party or feast. One tradition that includes paʻina is the four-month-long Makahiki festival. This ancient Hawaiian New Year festival honors the god Lono, who was known as the sweet potato god in the Hawaiian religion. Makahiki begins with spiritual cleansing and giving hoʻokupu (offerings) to the gods.

During this time, a class of royalty called Konohiki collected agricultural and seafood products as taxes. These included pigs, taro, sweet potatoes, dried fish, kapa (cloth), and mats. Some offerings were forest products like feathers.

The Hawaiian people did not use money. Goods were offered on altars to Lono at heiau (temples) in each district. Offerings were also made at ahu, which were stone altars at the boundaries of each community. All fighting was stopped during this time to allow the image of Lono to travel freely.

The festival moved clockwise around the island. Priests carried the image of Lono (a long pole with a strip of tapa and decorations). At each ahupuaʻa (community), the caretakers presented hoʻokupu to the Lono image. Lono was a god of fertility who brought growth, plenty, and wealth to the islands.

The second part of the celebration included hula dancing, sports (like boxing, wrestling, Hawaiian lava sledding, javelin throwing, bowling, surfing, canoe races, relays, and swimming), singing, and feasting. In the third part, the waʻa ʻauhau (tax canoe) was filled with hoʻokupu and taken out to sea. It was then set adrift as a gift to Lono.

At the end of the Makahiki festival, the chief would go offshore in a canoe. When he returned to shore, a group of warriors would throw spears at him. He had to block or dodge the spears to prove he was still worthy to rule.

Hawaiian Food Today

Native Hawaiian dishes have changed over time and are now part of modern fusion cuisine. While big lūʻau events are popular for tourists, traditional Hawaiian food is less common than other types of food in Hawaiʻi. However, some restaurants, like Helena's Hawaiian Food and Ono Hawaiian Foods, specialize in serving these traditional dishes.

See also

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |