Stanley Bruce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Bruce of Melbourne

|

|

|---|---|

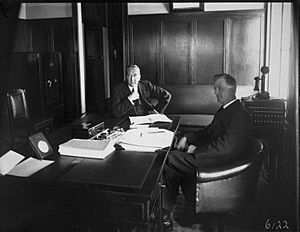

Bruce in 1930

|

|

| 8th Prime Minister of Australia | |

| In office 9 February 1923 – 22 October 1929 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Governor-General |

|

| Deputy | Earle Page |

| Preceded by | Billy Hughes |

| Succeeded by | James Scullin |

| Leader of the Nationalist Party | |

| In office 9 February 1923 – 22 October 1929 |

|

| Preceded by | Billy Hughes |

| Succeeded by | John Latham |

| Treasurer of Australia | |

| In office 21 December 1921 – 8 February 1923 |

|

| Prime Minister | Billy Hughes |

| Preceded by | Sir Joseph Cook |

| Succeeded by | Earle Page |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Flinders |

|

| In office 11 May 1918 – 12 October 1929 |

|

| Preceded by | William Irvine |

| Succeeded by | Jack Holloway |

| In office 19 December 1931 – 6 October 1933 |

|

| Preceded by | Jack Holloway |

| Succeeded by | James Fairbairn |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal |

|

| In office 18 March 1947 – 25 August 1967 Hereditary peerage |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Stanley Melbourne Bruce

15 April 1883 St Kilda, Colony of Victoria |

| Died | 25 August 1967 (aged 84) London, England |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Ethel Anderson

(m. 1913; died 1967) |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Melbourne Grammar School |

| Alma mater | Trinity Hall, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Commercial lawyer (Ashurst, Morris, Crisp & Co.) |

| Profession |

|

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1917 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 2nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards |

|

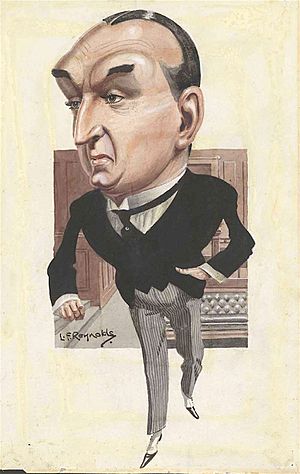

Stanley Melbourne Bruce (born 15 April 1883 – died 25 August 1967) was Australia's eighth Prime Minister. He led the Nationalist Party from 1923 to 1929.

Bruce came from a wealthy family in Melbourne. He studied at the University of Cambridge in England. After his father died, he took a big role in his family's business. During World War I, he fought in the Gallipoli Campaign and was injured. When he returned to Australia, he became a speaker for the government. This caught the eye of Prime Minister Billy Hughes, who encouraged him to enter politics.

In 1918, Bruce was elected to the Australian House of Representatives. He became the Treasurer in 1921. In 1923, he replaced Hughes as Prime Minister. He formed a government with the Country Party. This partnership was a first step towards the modern Liberal–National coalition in Australia.

As Prime Minister, Bruce worked on many different projects. He changed how the federal government was run. He also oversaw the move of the capital city to Canberra. He helped create important groups like the Australian Federal Police and the CSIRO. Bruce's "men, money and markets" plan aimed to grow Australia's population and economy. He wanted to do this through large government investments and stronger ties with Great Britain.

However, his efforts to change Australia's industrial laws often caused problems with workers. In 1929, he tried to get rid of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. This led to members of his own party voting against him. His government lost the election badly. Bruce even lost his own seat, which was very unusual for a sitting Prime Minister.

Bruce returned to parliament in 1931. But he soon chose to work on international issues. In 1933, he became Australia's High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. He became an important person in British government and at the League of Nations. He worked hard to encourage countries to work together on economic and social problems. He was especially keen on improving global nutrition. Bruce helped create the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and was its first chairman. He was also the first Australian to be a member of the House of Lords. He became the first Chancellor of the Australian National University. Bruce always spoke up for Australia's interests, even when living in London. When he died, his ashes were scattered over Canberra.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Military Service in World War I

- Early Political Career

- Prime Minister of Australia (1923–1929)

- Return to Cabinet (1931–1933)

- High Commissioner to the United Kingdom (1933–1945)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (1946–1951)

- Later Life and Legacy

- Death

- See also

- Images for kids

Early Life and Education

Stanley Melbourne Bruce was born on 15 April 1883 in St Kilda, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne. He was the youngest of five children. He didn't like his first name and preferred to be called "S.M." by his friends.

His father, John Munro Bruce, was born in Ireland and moved to Australia in 1858. His mother, Mary Ann Henderson, was also Irish. John Bruce was a very skilled businessman. He became a partner in a company called Paterson, Laing and Bruce. As he became richer, John Bruce became important in Victoria's social and political life. He helped start the Royal Melbourne Golf Club.

Stanley grew up in a wealthy family. They moved to a large house called Wombalano manor in Toorak. Stanley went to Melbourne Grammar School. He was an average student but loved sports. He was captain of the school's Australian football team. In 1901, he became the school captain.

After his father died in 1901, the family's money was not as good. Bruce started working in the family business after high school. He wanted to get a better education. He borrowed money and moved to the United Kingdom with his mother and sister. In 1902, he enrolled at Trinity Hall, Cambridge University. He was popular and very active in sports, especially rowing. He was part of the Cambridge rowing team that won the Boat Race in 1904. Rowing remained a big passion for him.

In 1906, Stanley became the chairman of Paterson, Laing and Bruce. He was only 23. He managed the company's exports and finances from London. His brother Ernest managed the business in Melbourne. The company and the family's money quickly improved. During these years, Bruce also trained and worked as a lawyer in London. His work took him to Mexico and Colombia, which made him interested in international affairs.

In 1912, Bruce met Ethel Dunlop Anderson again. He had known her as a child. Ethel was from a well-known family in Victoria. She shared many of Bruce's interests, including golf and politics. They got married in July 1913. They had a very close relationship. Bruce was deeply affected by the deaths of most of his family members. He and Ethel did not have children.

Military Service in World War I

Bruce returned to Australia briefly in 1914. World War I started in August of that year. Bruce and his brothers decided to join the British Army. It was easier to become an officer in the British Army. Bruce became a lieutenant in February 1915. He was sent to Egypt with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers.

His unit later joined the Gallipoli Campaign in Turkey. Bruce showed great skill in building trenches and leading his soldiers. His battalion suffered many losses. Bruce was wounded on 3 June by a shot to the arm. This injury saved him from a major attack the next day, where many of his friends died. He later felt that he was kept alive for a special purpose.

He returned to the front lines and was involved in heavy fighting. Bruce received the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre for his bravery. He was promoted to captain on 5 August. He was wounded again on 26 September, this time in the knee. This injury made him unable to fight for several years. He had to return to England to recover.

In 1916, Bruce wanted to leave the army and go back to Australia to manage his family's business. The War Office refused at first. But they gave him leave to return to Australia while he recovered. As a decorated soldier who could speak well, he was asked to help with government recruitment efforts in Australia. His success caught the attention of Prime Minister Billy Hughes. Hughes helped Bruce get permission to leave the army in June 1917.

Bruce had served with many Australians and felt a strong connection to his home country. He had seen terrible loss of life in Gallipoli. He was determined to make something of his life.

Early Political Career

Bruce's popularity as a speaker helped him get noticed by a powerful group of Melbourne businessmen. This group helped fund the Nationalist Party. In 1918, a special election was held for the seat of Division of Flinders. Bruce was asked to run. He won the election easily against his opponent.

His first few years in parliament were quiet. He focused mainly on his family's business. But in 1921, he gained attention for his views on the Commonwealth Line. This was a state-owned shipping company created by Prime Minister Billy Hughes. Bruce argued that it was not efficient. Many other politicians who believed in less government spending agreed with him.

Bruce also represented Australia at the League of Nations in Geneva in 1921. He spoke strongly for countries to reduce their weapons and work together.

Becoming Treasurer

In October 1921, Prime Minister Billy Hughes asked Bruce to join his government. Bruce was offered the role of Minister for Trade and Customs. Bruce wasn't interested because his business was in importing, which would be a conflict of interest. He suggested he might accept the job of Treasurer instead. To his surprise, Hughes agreed.

Bruce had only been in parliament for three years. But his business background was very useful to Hughes. Hughes was facing criticism from business leaders in his party. Bruce and Hughes had different styles and ideas. Bruce found Hughes's way of running the government messy. But Bruce was a strong voice against Hughes's more expensive ideas. He helped Hughes make more sensible decisions.

Bruce was Treasurer for a short time, presenting only one budget in 1922. It was a careful budget that cut taxes. The Opposition criticized it for not controlling government spending. But Bruce became popular with many of his colleagues. They liked his friendly style and his conservative views.

Prime Minister of Australia (1923–1929)

In the 1922 election, the Nationalists lost many seats. They no longer had a majority in the Australian House of Representatives. The Labor Party didn't have enough seats to form a government either. The Country Party gained more seats and now held the power to decide who would govern.

Country Party leader Earle Page refused to support a Nationalist government if Billy Hughes was still Prime Minister. After weeks of talks, Hughes decided to resign in February 1923. Hughes then asked Bruce to become the new leader of the party. Bruce agreed.

Bruce quickly worked to get enough support for his government. He made a deal with the Country Party. This deal was called the Coalition. It meant the Nationalists and Country Party would work together in elections and in government. The Country Party received five positions in the Cabinet. Earle Page became Treasurer and was second in command. This was a big step for Australian politics. Page greatly admired Bruce, calling him a leader who impressed his colleagues with his wisdom.

Bruce became Prime Minister on 9 February 1923. He was the first Prime Minister who was not involved in the movement to create Federation. He was also the first Prime Minister to lead a government made up entirely of Australian-born ministers. However, people sometimes joked that Bruce seemed "too English" for Australia. He drove a fancy car and was seen as distant from ordinary people.

"Men, Money, and Markets" Plan

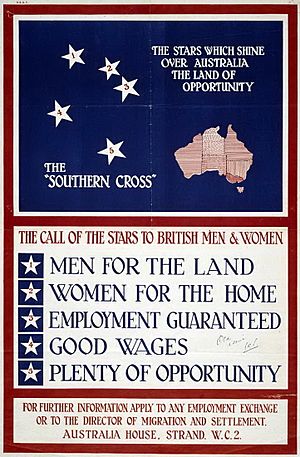

In 1923, Australia was doing well economically after World War I. Unemployment was low, and government income was growing. Australia was a huge country with lots of resources but fewer than six million people. Bruce wanted to develop Australia's economy. He called his plan "men, money and markets."

- Men: Bruce believed Australia needed more people to develop its resources. He thought Australia could support over 100 million people. His government encouraged many British people to move to Australia. They offered loans and help for immigrants to settle, especially in rural areas. Over 200,000 British immigrants came to Australia during this time. However, most settled in cities, not rural areas. The government also kept the White Australia policy, which limited immigration from other countries.

- Money: Australia borrowed a lot of money from Britain to fund its development plans. Over £230 million was borrowed from London in the 1920s. Bruce wanted the federal government to have a stronger role in the economy. He and Page wanted to change how the federal and state governments worked together. The Main Roads Development Act of 1923 was an important law. It allowed the federal government to give money to states for road building. This gave the federal government more power in areas usually controlled by the states.

- Markets: Bruce wanted to improve Australia's trade with the British Empire. He pushed for "trade preference" for products from Empire countries. This meant that goods from Australia would be favored over goods from other nations. However, this idea was not popular in Britain. The British public worried about higher prices for food. This plan did not fully happen.

By 1927, Australia's economy was starting to struggle. Prices for Australian exports were falling. Australia's debt was very high, and investors were worried. Bruce believed that increasing exports was the key to fixing the problems.

He also worked to manage the debt problem. States were borrowing too much money. Bruce suggested creating a National Loan Council. This council would manage all government debts (federal and state) and control new borrowing. This change was approved by a referendum in 1928. These changes meant states lost much of their financial independence.

Modernizing Government

Bruce brought his business skills to his government. He created a formal system for Cabinet meetings. Ministers would share papers to inform others about issues. This made sure everyone was informed and involved in decisions. His colleagues respected him for his hard work and knowledge.

Bruce also greatly improved the government's ability to research and gather information. He wanted decisions to be based on facts. His government set up many Royal Commissions and research projects. He created the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), now known as the CSIRO. This group helped with scientific research for agriculture and the economy. He also hired economists to advise the government. By the time he left office, the Prime Minister's office had much more professional support.

Under Bruce, the Australian government also moved to its new home in Canberra. Plans for a new capital city had been around since Federation. Bruce strongly supported the move. He believed Australia needed a central capital. On 9 May 1927, the Federal Parliament moved to its new building in Canberra. Bruce and his wife had moved into The Lodge a few days earlier. The process of moving government departments to Canberra took time.

Imperial Relations

Bruce believed in strengthening the British Empire. He wanted more economic development, political cooperation, and common policies on defense and trade. In 1923, he went to the Imperial Conference in London. He proposed many ideas for Great Britain and its dominions (like Australia) to work more closely. He wanted the dominions to have a bigger say in Empire affairs.

He was concerned when Britain made foreign policy decisions without consulting Australia. For example, in 1922, Britain almost went to war with Turkey without telling the dominions. Bruce pushed for more consultation. He succeeded in having Richard Casey appointed as a permanent contact in London. This person would keep Australia informed about British government decisions. He also helped create a separate Dominion Office. This showed that dominions were different from colonies.

However, other dominions like Canada and South Africa wanted more independence, not closer ties. The 1926 Imperial Conference showed that Britain and its dominions were growing apart. The Balfour Declaration from this conference stated that dominions were essentially independent countries. They were freely associated as the British Commonwealth of Nations. Bruce had mixed feelings about this. He still believed the Empire was important. But he was disappointed that other nations didn't share his vision for its unity.

Industrial Relations Challenges

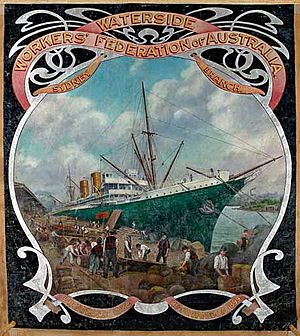

After World War I, there were many strikes and worker protests. This was due to poor working conditions and the rise of groups like the Communist Party of Australia. The problem was made worse by Australia's system of industrial courts. Both state and federal courts could deal with worker disputes. This led to confusion and long arguments. Unions and employers would choose the court they thought would give them the best outcome.

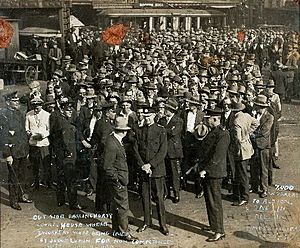

Bruce initially wanted businesses and workers to cooperate. But the situation became serious when waterfront workers went on strike in 1925. This strike badly affected Australia's economy. Bruce passed new laws to deal with it. One law allowed the government to deport foreign-born people who were "disrupting industrial life." Some strike leaders were targeted for deportation. Bruce also created a Commonwealth police force.

These strong actions angered the Labor Party. Bruce called an election in 1925. He campaigned for industrial peace and a stronger federal role in achieving it. He also spoke out against "foreign agitators." His campaign was successful, and his government was re-elected easily.

Bruce then called for a referendum to change the Australian Constitution. He wanted to give the federal government full control over industrial relations. But the proposal did not get enough public support and failed.

Strikes continued, especially on the waterfront. In 1928, Bruce changed the law so that industrial courts had to consider the economic effects of their decisions. This led to worse conditions for waterside workers. New strikes broke out, leading to riots in Melbourne. Bruce passed the Transport Workers Act. This law required all waterfront workers to have federal licenses, nicknamed "dog collars." This law gave the government a lot of power over who could work on the docks. It made the government very unpopular with workers.

In the 1928 election, Bruce's government won again, but with a much smaller majority. The Labor Party, now led by James Scullin, was stronger. Bruce believed that Australia needed to lower production costs and achieve industrial peace to avoid a major economic crisis.

The End of His Prime Ministership

By 1927, signs of an economic slowdown were appearing. By 1929, it was clear that a depression was starting. Prices for Australian exports fell sharply. Australia's debt was huge, and banks were worried. Bruce's big economic plans had increased debt but hadn't brought enough economic growth.

Strikes continued to be a problem, especially in New South Wales. In 1929, there were major disputes between miners and mine owners. Bruce's government tried to intervene but was seen as siding with the mine owners. This hurt Bruce's image as a fair leader.

Bruce became very frustrated with the ongoing industrial problems. He made a bold move. He told the state governments they must either give their power over industrial laws to the federal government, or the federal government would give up its own industrial powers. This surprised everyone, even his own Cabinet. Bruce believed the states wouldn't give up their powers, so this would end federal arbitration.

He introduced the Maritime Industries Bill to parliament. Many people opposed it. Over 700,000 workers were covered by federal awards, and most were happy with them. They feared worse pay and conditions under state laws. Bruce argued his actions were needed to create certainty and end confusion.

The bill passed its second reading by only four votes. Former Prime Minister Billy Hughes and others voted against the government. Hughes then proposed an amendment. He said the bill should only take effect if approved by the people in a referendum or election. Bruce said this amendment was a vote of no confidence in his government. He urged his party to vote it down. But some members of his own party voted with the opposition. This meant the government lost the vote by one vote.

A snap election was called. Bruce argued that strong action on industrial relations was needed. Opposition Leader Scullin strongly attacked the government. He blamed Bruce for creating a difficult environment for workers. Scullin also criticized the government for the growing debt and economic problems.

In the election on 12 October, Bruce's government was soundly defeated. They lost more than half their seats. To make matters worse, Bruce lost his own seat of Flinders to the Labor candidate, Jack Holloway. Bruce was the first sitting Prime Minister to lose his seat. He accepted his defeat, saying, "The people have said they do not want my services."

Return to Cabinet (1931–1933)

After his defeat, Bruce went back to England to holiday and work on his business. Sir John Latham took over as leader of the Nationalists. With the stock market crash in 1929 and the start of the Great Depression in Australia, Bruce felt that his government's defeat was probably a good thing. He defended his time as Prime Minister, saying the economic crisis was unavoidable.

In April 1931, he announced he would return to politics. The Nationalists had reformed as the United Australia Party (UAP) under Joseph Lyons. In November 1931, the Scullin government was defeated. A new election was called. Bruce was in England at the time. The Scullin government lost badly. Bruce won back his old seat of Flinders, even though he wasn't in Australia.

He was appointed Assistant Treasurer in the new Lyons Government. Lyons relied heavily on Bruce. Bruce, however, was now more interested in international affairs than Australia's domestic problems.

Bruce led the Australian team to the 1932 Imperial Economic Conference in Ottawa. He worked hard to improve Australia's economic ties with the Empire. The conference agreed to a limited form of his long-desired imperial trade preference scheme. This gave Australia better access to Empire markets for five years. Bruce received much praise for this achievement. These trade agreements set the pattern for Australian-British trade until Britain joined the European Common Market in 1973.

After this success, Lyons appointed Bruce as Resident Minister in the United Kingdom. London became his and Ethel's home for the rest of their lives. His first job was to renegotiate Australia's large government debts. He successfully negotiated new loan terms that saved Australia millions of pounds. Bruce was asked several times in the 1930s to return to Australia to become Prime Minister again. But he showed little interest.

High Commissioner to the United Kingdom (1933–1945)

In September 1933, Bruce was appointed High Commissioner to the United Kingdom. This gave him the rank of an ambassador. He officially resigned from parliament on 7 October 1933. Bruce was very good at this new job. He became a trusted advisor to British politicians. He was especially close to Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. Bruce was also important in pushing for King Edward VIII's abdication in 1936.

Bruce was seen as Australia's most influential international representative. He often made foreign policy decisions on his own.

Work at the League of Nations

Bruce represented Australia at the League of Nations. He helped Australia become a member of the League Council from 1933 to 1936. He disagreed with taking strong action against Japan after their invasion of Manchuria in 1933. He was worried about Australia's trade with Japan and future peace in the Pacific. He believed the League was not strong enough to enforce sanctions.

During the Abyssinia Crisis, Bruce again advised against sanctions. He thought they would not stop the invasion of Ethiopia and would upset Italy. He argued that Britain and France needed to build up their armies. Bruce became the president of the League of Nations Council in 1936. He tried to stop the invasion, but it failed. He also presided during the Rhineland Crisis, where attempts to stop fascist aggression failed again.

Bruce still believed in the League's potential. But he thought it needed major changes. He chaired the 1936 Montreux Conference. This conference successfully reached an international agreement on passage through the Turkish Straits. This was important to Bruce as a veteran of the Gallipoli campaign.

By 1937, Bruce focused on social and economic cooperation. He believed this had more chance of success. He played a leading role in promoting agriculture, nutrition, and economic cooperation through the League. In 1937, he proposed a plan to ease international tensions. It aimed to revive international trade and improve living standards in Europe. He believed that economic hardship could push nations towards fascism or communism.

His work led to the creation of the Bruce committee in 1939. This committee suggested expanding the League's role to include many economic and social programs. However, their work was stopped by the start of World War II.

World War II Efforts

Before World War II, Bruce supported Britain's policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. He believed that negotiation was better than war. Bruce even took part in the talks for the Munich Agreement. When Prime Minister Lyons died in 1939, Bruce was asked to return to Australia and become Prime Minister again. But he refused.

When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Australia followed within hours. When Winston Churchill became British Prime Minister in May 1940, Bruce often disagreed with him. Churchill saw the dominions as still dependent colonies. Bruce saw the Empire as a partnership. Britain's focus on Europe worried Australian politicians. They were concerned about Japanese invasion in the Far East.

After several defeats in the Far East, especially the Fall of Singapore, Australia succeeded in getting Bruce a place in the British War Cabinet. However, Bruce often found himself left out of meetings. He directly challenged Churchill many times about the lack of consultation with Australia. Churchill often ignored him. Bruce continued in this difficult role until May 1944, when he resigned. Despite his difficult relationship with Churchill, Bruce was highly respected by other Cabinet members. He worked tirelessly to advance Australia's interests during the war.

Food and Agriculture Organization (1946–1951)

By the end of World War II in 1945, Bruce was tired of his High Commissioner job. He had imagined a post-war world with a new international body, like the League of Nations but stronger. Bruce rejoined Frank L. McDougall and John Boyd Orr to work on their ideas for international cooperation on nutrition and agriculture. He became a leading voice for creating a global organization to address social and economic issues.

Their efforts led to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). This organization was formally established in October 1945 and became part of the United Nations. Bruce was considered to be the first Secretary-General of the United Nations. But he felt he was too old. In 1946, he became chairman of the FAO Preparatory Commission. This group aimed to create a "world food board" to coordinate international nutrition policy. He proposed ideas like a world food reserve and special pricing to help distribute food where it was needed.

Bruce's Commission also emphasized modernizing agriculture and international development aid. These proposals were never fully adopted due to their high costs and challenges to national sovereignty.

Despite this, Bruce was elected Chairman of the new FAO Council in November 1947. He worked with John Boyd Orr, who was now the FAO's Secretary-General. There were severe food shortages after the war. Bruce and the council worked to distribute fertilizer and agricultural machinery. They also worked to improve nutrition, especially in developing countries. Bruce felt it was important to show developed nations the stark facts about global hunger.

In November 1949, an important agreement was reached between the FAO and the United Nations. This gave the FAO funding and support to act on the food crisis. Bruce and the FAO helped world agricultural output recover to pre-war levels by 1951. However, this growth was not fast enough to keep up with the post-war population boom. Bruce and Orr resigned from the FAO, disappointed that it couldn't fully solve world food problems.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Bruce held various positions in the United Kingdom and Australia. He was Chairman of the Finance Corporation of Industry from 1946 to 1957. He helped establish a similar program in Australia. In 1952, he became the first Chancellor of the new Australian National University. He was very involved in its development, especially as a research center for Asia and the Pacific. Bruce Hall, a residential college, was named after him.

In 1947, he became the first Australian to be a member of the House of Lords. He was given the title Viscount Bruce of Melbourne. He was active in the House of Lords until his death. He continued to speak about international and national social and economic issues. He also promoted Australia's recognition within the Commonwealth. He kept lobbying the British government to increase its help for developing countries.

Bruce was a keen golfer his whole life. In 1954, he became the first Australian captain of The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews. He also continued to coach rowing at Cambridge University.

Death

Bruce remained active and healthy in his retirement, despite gradually losing his hearing. But the death of his wife Ethel in March 1967 deeply affected him. He died on 25 August 1967, at the age of 84. He was the last surviving member of Billy Hughes's government. His memorial service was held in London and was well attended. His ashes were scattered over Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra. The Canberra suburb of Bruce and the electoral Division of Bruce in Melbourne are named after him.

Despite his many achievements, Bruce's work after being Prime Minister was not well known in Australia. Most Australians remembered his strict laws against unions and his government's big election loss in 1929. He was often seen as a distant man, too English for Australia. However, he never forgot his Australian roots and always worked hard for Australia's interests. He spent much of his later career trying to solve problems for the world's poorest people.

Bruce was ambitious and aimed high. As Prime Minister, he worked on big plans for economic and social development. In his diplomatic career, he pushed for better treatment for the Commonwealth. He also worked through the League of Nations and United Nations to solve global social and economic problems. His most ambitious work was to end world hunger through the Food and Agriculture Organization. The Australian government even nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Bruce himself admitted he was "forever buying into things that aren't really my concern." But despite not being widely recognized in Australia, historians and his peers saw his lasting impact. Sir John Cockcroft, who followed him as Chancellor of the Australian National University, called him "probably the outstanding Australian of our time."

See also

In Spanish: Stanley Bruce para niños

In Spanish: Stanley Bruce para niños

- First Bruce Ministry

- Second Bruce Ministry

- Third Bruce Ministry

Images for kids