Federation of Australia facts for kids

The Federation of Australia was a big step where six separate British colonies in Australia decided to join together. These colonies were Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also included the Northern Territory back then), and Western Australia. They all agreed to form one country called the Commonwealth of Australia.

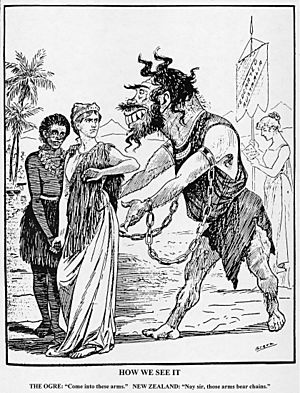

Originally, Fiji and New Zealand were also part of the discussions, but they chose not to join. After Federation, the six colonies became states. They kept their own governments and parliaments, but they also created a new federal government. This federal government would handle matters that affected the whole nation. On 1 January 1901, the Constitution of Australia came into effect, and the colonies officially became states of the Commonwealth of Australia.

In the mid-1800s, there wasn't much public support for joining the colonies. However, during the 1890s, several important meetings were held to create a constitution for the new Commonwealth. Sir Henry Parkes, who was the Premier of New South Wales, played a huge role in this process. Sir Edmund Barton was another key figure. He became the first Prime Minister of Australia after the first national election in March 1901.

One of the main economic changes from Federation was the creation of a single customs and tax system for Australia. This meant that goods moving between the new states would no longer have extra taxes, making trade easier across the country.

The time of Federation also gave its name to a popular building style in Australia called Federation architecture.

Contents

Early Ideas for a United Australia

Even as far back as 1842, people were talking about uniting the Australian colonies. An article in the South Australian Magazine suggested a "Union of the Australasian Colonies." Later, in 1846, Sir Edward Deas Thomson, a government official in New South Wales, also proposed the idea. The Governor of New South Wales, Sir Charles Fitzroy, even wrote to the British government suggesting a "superior functionary" who could oversee laws from all the colonies.

In 1847, the British government's Secretary of State for the Colonies, Earl Grey, even drew up a plan for a "General Assembly" of the colonies. But the idea didn't go anywhere at that time. In 1857, Deas Thomson tried again, suggesting a committee in New South Wales to look into Australian federation. The committee supported the idea, but the government changed, and the plan was put aside.

The Federal Council of Australasia

A more serious push for Federation began in the late 1880s. At this time, many Australians, especially those born in the country, felt a stronger sense of national pride. Songs and poems celebrated being "Australian." Travel and communication also improved, like the telegraph system connecting the colonies in 1872. Australians also looked at other countries that had formed federations, like the United States and Canada.

Sir Henry Parkes first suggested a Federal Council in 1867. After it was rejected, he brought up the idea again in 1880 as the Premier of New South Wales. At a meeting, representatives from Victoria, New South Wales, and South Australia discussed many topics, including federation, communication, and trade rules. Federation could help make trade easier across the continent by removing taxes between colonies and standardising measurements and transport.

The final push for a Federal Council happened at a meeting in Sydney in late 1883. This was partly because the British government didn't approve Queensland's attempt to take over New Guinea on its own. The British wanted to see a more united Australasia. The meeting discussed how to deal with the actions of Germany and France in New Guinea and the New Hebrides. Sir Samuel Griffith, the Premier of Queensland, wrote a bill to create the Federal Council. The meeting successfully asked the British Parliament to pass this bill, which became the Federal Council of Australasia Act 1885.

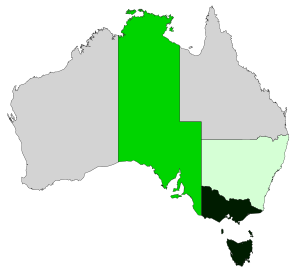

This led to the creation of the Federal Council of Australasia. It was meant to handle matters concerning the colonies' relations with the South Pacific islands. New South Wales and New Zealand did not join. Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and Fiji became members. South Australia was a member for a short time. The Federal Council could make laws on certain topics, like recognising citizens from other colonies or regulating workers from the Pacific Islands. However, it didn't have its own staff, executive powers, or money. Also, New South Wales, a powerful colony, was not a member, which made the Council less effective.

Despite its weaknesses, the Federal Council was the first major step towards cooperation between the colonies. It allowed people who supported Federation from different parts of the country to meet and share ideas. The way the Council was set up also showed that the British Parliament would continue to play a role in Australia's government structure. Many of the powers given to the Federal Council later appeared in the Australian Constitution, especially in Section 51.

Early Concerns About Federation

Most colonies, except Victoria, were a bit worried about Federation. Politicians, especially from the smaller colonies, didn't like the idea of giving power to a national government. They feared that a federal government would be controlled by the larger colonies like New South Wales and Victoria. Queensland was concerned that national laws about immigration might limit the use of Pacific Islander labourers, which could harm its sugar cane industry.

Other concerns included the removal of tariffs (taxes on goods). This would mean smaller colonies would lose a lot of their income. New South Wales, which preferred free trade, wanted to make sure the new federal government's trade policy wouldn't be protectionist (meaning high taxes on imports). Victorian Premier James Service called this financial issue "the lion in the way" of federation.

Another big question was how the federal government would share customs money with the states. Larger colonies worried they might have to support the economies of Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia.

People also debated what kind of government a federation would have. Examples from other federations weren't always encouraging. For instance, the United States had experienced a terrible Civil War.

The growing Australian labour movement had mixed feelings about federation. On one hand, they felt a strong sense of national pride and supported the idea of controlling who could enter the country. On the other hand, labour representatives worried that federation would take attention away from important social and industrial reforms. They also felt the proposed federal constitution was too conservative. They wanted a federal government with more power to make laws about things like wages and prices. They also thought the proposed Senate would be too powerful and could block social reforms, just like the colonial upper houses were doing at the time.

Religious differences also played a small part. Generally, leaders who supported federation were Protestants. Catholics were less enthusiastic, partly because Henry Parkes had been strongly anti-Catholic for many years. However, many Irish Australians felt a connection between the idea of Home Rule in Ireland (which was like a federation for the UK) and the federation of the Australian colonies. Leaders like Edmund Barton made sure to keep good relations with Irish communities.

Early Meetings to Write the Constitution

In the early 1890s, two important meetings helped set the stage for Federation. An informal meeting with representatives from the Australian colonies was held in 1890. This led to the first National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891. New Zealand attended both meetings, but its delegates said they probably wouldn't join at the start, but might later.

Australasian Federal Conference of 1890

The Australasian Federal Conference of 1890 was called by Henry Parkes. The story goes that Lord Carrington, the Governor of New South Wales, challenged Parkes in June 1889. Parkes supposedly boasted he "could confederate these colonies in twelve months." Carrington replied, "Then why don't you do it? It would be a glorious finish to your life." The next day, Parkes wrote to the Premier of Victoria, Duncan Gillies, to push for Federation. Gillies was cautious, as Parkes had been slow to bring New South Wales into the Federal Council. In October, Parkes travelled to Brisbane and met with Griffith. On his way back, he stopped near the border and gave the famous Tenterfield Oration on 24 October 1889, saying it was time for the colonies to consider Australian federation.

Throughout late 1889, the premiers and governors discussed and agreed to hold an informal meeting. Key attendees included: Parkes and William McMillan from New South Wales; Duncan Gillies and Alfred Deakin from Victoria; Sir Samuel Griffith and John Murtagh Macrossan from Queensland; Dr. John Cockburn and Thomas Playford from South Australia; Andrew Inglis Clark and Stafford Bird from Tasmania; Sir James George Lee Steere from Western Australia; and Captain William Russell and Sir John Hall from New Zealand.

When the conference met at the Victorian Parliament in Melbourne on 6 February, it was a very hot day. The delegates discussed whether it was the right time to move forward with federation.

Some delegates agreed, but the smaller states were less keen. Thomas Playford from South Australia pointed out that the issue of tariffs and a lack of public support were obstacles. Similarly, Sir James Lee Steere from Western Australia and the New Zealand delegates said there was little support for federation in their colonies.

A basic question at this early meeting was how to set up the new federal government, following the Westminster system. The British North America Act, 1867, which had united the Canadian provinces, offered a model for how the federation would relate to the British Crown. However, there was less interest in the strong central government of the Canadian Constitution, especially from the smaller states. After the 1890 conference, the Canadian model was no longer seen as suitable for Australia.

Although the Swiss Federal Constitution was another example, the delegates naturally looked to the Constitution of the United States as the other main model for a federation in the English-speaking world. The US Constitution gave only a few powers to the federal government, leaving most matters to the states. It also said that the Senate should have an equal number of members from each state, while the Lower House should represent the population distribution. Andrew Inglis Clark, who admired American federal systems, presented the US Constitution as a way to protect states' rights. He argued that Canada was more like a "merger" than a true "Federation."

Clark's Draft Constitution

Andrew Inglis Clark had thought a lot about a good constitution for Australia. In May 1890, he went to London for a legal case. During this trip, he started writing a draft constitution. He used parts of the British North America Act, 1867, the US Constitution, the Federal Council of Australasia Act, and various Australian colonial constitutions. Clark returned from London via Boston, Massachusetts, where he discussed his draft with important legal figures.

Clark's draft introduced the names and structure that were later adopted:

- The Australian Federation was called the Commonwealth of Australia.

- It had three separate and equal parts: the Parliament, the Executive (government leaders), and the Judicature (courts).

- The Parliament had two houses: a House of Representatives and a Senate.

- It clearly defined the separation of powers and the division of powers between the Federal and State governments.

When he returned to Hobart in late 1890, Clark finished his draft Constitution with help from W. O. Wise, the Tasmanian Parliamentary Draftsman. He printed several copies. In February 1891, Clark shared his draft with Parkes, Barton, and probably Playford. This draft was meant to be a private working document and was never officially published.

The National Australasian Convention of 1891

The Parliament proposed at the 1891 Convention was to use names similar to the United States Congress: a House of Representatives and a Senate. The House of Representatives would be elected based on population in different areas, while the Senate would have equal representation for each "province" (state). This American model was combined with the Westminster system, where the Prime Minister and other ministers would be chosen by the representative of the British Crown from the political party that had the most members in the lower house.

At the Sydney Convention, Griffith clearly pointed out a major challenge: how to structure the relationship between the lower and upper houses in the Federal Parliament. The main disagreement was between Alfred Deakin, who believed the lower house should be supreme, and Barton, John Cockburn, and others, who thought a strong Senate with equal powers was essential. Griffith himself suggested that the idea of responsible government (where the government is accountable to parliament) should be flexible or changed to fit the federal structure.

Over the Easter weekend in 1891, Griffith edited Clark's draft on the Queensland Government's steam yacht, Lucinda. Clark was not there because he was sick in Sydney. Griffith's draft Constitution was then sent to the colonial parliaments. However, it failed to pass in New South Wales, and because of that, the other colonies decided not to continue with it at that time.

Griffith or Clark?

The importance of the 1891 draft Constitution was highlighted by John La Nauze, who said, "The draft of 1891 is the Constitution of 1900, not its father or grandfather." However, in recent years, there has been a debate about whether the main credit for this draft belongs to Queensland's Sir Samuel Griffith or Tasmania's Andrew Inglis Clark. This discussion started with books published in the early 2000s.

The traditional view was that Griffith was almost entirely responsible for the 1891 draft. Quick and Garran, who were active in the federal movement, stated that Griffith "had the chief hand in the actual drafting of the Bill." This suggests that this was the common belief among Australia's "founding fathers."

However, Henry Reynolds, in his 1969 entry on Clark for the Australian Dictionary of Biography, offered a more balanced view. He noted that Clark had circulated his own draft constitution bill before the 1891 Convention. This draft was a collection of relevant parts from other constitutions, but it was very useful to the drafting committee. Clark's draft also suggested a separate federal court system, which would replace the British Privy Council as the highest court. Clark was on the Constitutional Committee and helped Griffith, Barton, and Charles Cameron Kingston revise Griffith's draft on the Lucinda. Even though Clark was too ill to be there for the main work, his own draft had been the basis for much of Griffith's text.

Clark's supporters point out that 86 out of 128 sections of the final Australian Constitution can be found in Clark's draft, and that "only eight of Inglis Clark's ninety-six clauses failed to find their way into the final Australian Constitution." However, Professor John Williams explains that these numbers can be misleading. He says that once the basic structure of a constitution is decided (like having an executive, parliament, and judiciary), there aren't many major changes left to make. He also notes that Clark's Constitution was not as clear or concise as the drafts by Charles Kingston and Sir Samuel Griffith, who were known for being direct and economical with words.

Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–98

The excitement for Federation that was present in 1891 quickly faded. This was partly due to opposition from Henry Parkes' rival, George Reid, and the rise of the Labor Party in New South Wales, which often dismissed federation as just a "fad." The federal movement gained new life thanks to the growth of federal leagues outside the big cities and, in Victoria, the Australian Natives' Association. A conference in Corowa in 1893 was very important. At this conference, John Quick proposed a plan for a convention elected by the people to write a constitution. This constitution would then be put to a vote (a referendum) in each colony. George Reid, who became premier of New South Wales in 1894, supported Quick's plan, and all premiers approved it in 1895.

In March 1897, elections were held for the Australasian Federal Convention Elections. Several weeks later, the delegates met for the Convention's first session in Adelaide. They later met in Sydney and finally in Melbourne in March 1898. After the Adelaide meeting, the colonial parliaments discussed the proposed bill and suggested changes. The main ideas from the 1891 draft constitution were adopted, but with more emphasis on democracy. For example, it was agreed that the Senate should be chosen directly by popular vote, not appointed by state governments.

There were many disagreements on other issues, especially those involving rivers and railways, which led to legal compromises. The delegates had few clear guides for what they were doing. Deakin praised James Bryce's book on American federalism, The American Commonwealth. Barton also mentioned other writers who analysed federation. However, for many delegates, the main example of how different governments could work together was the British Empire, which was not a federation at all.

The Australasian Federal Convention finished on 17 March 1898, after adopting a bill called "To Constitute the Commonwealth of Australia."

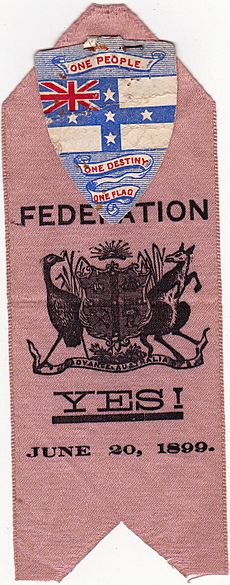

Referendums (public votes) on the proposed constitution were held in four colonies in June 1898. Most people voted "yes" in all four colonies. However, in New South Wales, the law required at least 80,000 "yes" votes, which was about half of all registered voters. This number was not reached. A meeting of the colonial premiers in early 1899 agreed to make some changes to the constitution to make it more acceptable to New South Wales. These changes included: limiting the "Braddon Clause" (which gave states 75% of customs revenue) to just ten years; requiring the new federal capital to be in New South Wales, but at least 160 km from Sydney; and changing the majority needed for a joint meeting of the Senate and House after a "double dissolution" from six-tenths to one-half. In June 1899, referendums on the revised constitution were held again in all colonies except Western Australia, where the vote happened the following year. The majority voted "yes" in all colonies.

1898 Referendums

| State | Date | For | Against | Total | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| Tasmania | 3 June 1898 | 11,797 | 81.29 | 2,716 | 18.71 | 14,513 | 25.0 |

| New South Wales | 3 June 1898 | 71,595 | 51.95 | 66,228 | 48.05 | 137,823 | 43.5 |

| Victoria | 3 June 1898 | 100,520 | 81.98 | 22,099 | 18.02 | 122,619 | 50.3 |

| South Australia | 4 June 1898 | 35,800 | 67.39 | 17,320 | 20.54 | 53,120 | 30.9 |

1899 and 1900 Referendums

| State | Date | For | Against | Total | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| South Australia | 29 April 1899 | 65,990 | 79.46 | 17,053 | 20.54 | 83,043 | 54.4 |

| New South Wales | 20 June 1899 | 107,420 | 56.49 | 82,741 | 43.51 | 190,161 | 63.4 |

| Tasmania | 27 July 1899 | 13,437 | 94.40 | 791 | 5.60 | 14,234 | 41.8 |

| Victoria | 27 July 1899 | 152,653 | 93.96 | 9,805 | 6.04 | 162,458 | 56.3 |

| Queensland | 2 September 1899 | 38,488 | 55.39 | 30,996 | 44.61 | 69,484 | 54.4 |

| Western Australia | 31 July 1900 | 44,800 | 69.47 | 19,691 | 30.53 | 64,491 | 67.1 |

The bill, accepted by most colonies (Western Australia voted after the British Parliament passed the act), was sent to Britain to become law.

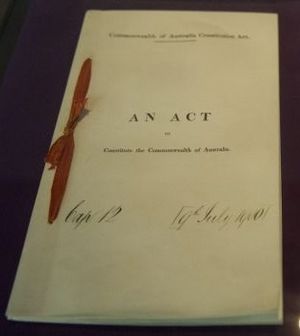

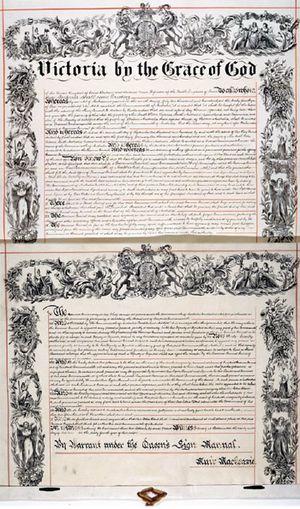

The Federal Constitution

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK) was passed on 5 July 1900. Queen Victoria gave it her official approval on 9 July 1900. It was officially announced on 1 January 1901 in Centennial Park, Sydney. Sir Edmund Barton was sworn in as the first interim Prime Minister, leading a temporary federal government with nine members.

The new constitution created a Parliament with two houses: a Senate and a House of Representatives. The role of Governor-General was also created as the Queen's representative. At first, this person was seen as a representative of the British Government.

The Constitution also set up a High Court. It divided the powers of government between the states and the new Commonwealth government. The states kept their own parliaments and most of their existing powers. However, the federal government became responsible for matters like defence, immigration, quarantine, customs, banking, and currency, among other things.

Places Named After Federation

Federation was such an important event for Australia that many places, both natural and man-made, have been named after it. These include:

- Federal Highway, which connects Goulburn, New South Wales, and Canberra.

- Federation Creek, near Croydon, Queensland.

- Federation Peak, a mountain in Tasmania.

- Federation Range, a mountain range on the Royston River, about 90 km east-northeast of Melbourne, Victoria.

- Federation Square, a public space in Melbourne, Victoria.

- Federation Trail, a walking and cycling path in Melbourne, Victoria.

- Federation University, a university in Ballarat, Victoria.

See also

In Spanish: Federación de Australia para niños

In Spanish: Federación de Australia para niños

Images for kids

-

The Sydney Town Hall lit up with lights and fireworks to celebrate the start of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. The sign says One people, one destiny.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |