German Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

German Empire

Deutsches Kaiserreich

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871–1918 | |||||||||

|

Motto: Gott mit Uns

(German: "God with us”) |

|||||||||

|

Anthem: Heil dir im Siegerkranz (unofficial)

|

|||||||||

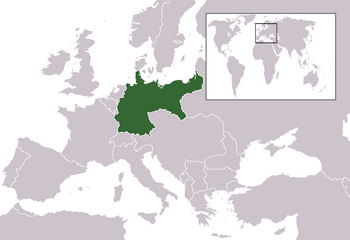

Territory of the German Empire in 1914, prior to World War I

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||||||

| Common languages | German Polish (Posen, Upper Silesia, Masuria) French (Lothringen region of Elsass-Lothringen) |

||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

|

• 1871-1888

|

Wilhelm I | ||||||||

|

• 1888-1888

|

Friedrich | ||||||||

|

• 1888-1918

|

Wilhelm II | ||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||

|

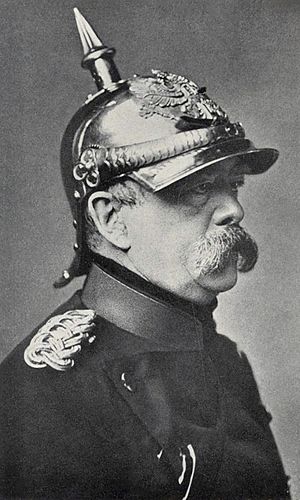

• 1871-1890

|

Otto von Bismarck | ||||||||

|

• 3 Oct-9 Nov 1918

|

Max von Baden | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Victory in the Franco-Prussian War

|

January 18 1871 | ||||||||

|

• Proclamation of the Weimar Republic

|

November 9 1918 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1910 | 540,766 km2 (208,791 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

|

• 1871

|

41058792 | ||||||||

|

• 1890

|

49428470 | ||||||||

|

• 1910

|

64925993 | ||||||||

| Currency | Goldmark | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | DE | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

The German Empire was a powerful country in Europe. It existed from January 18, 1871, to November 9, 1918. This period started when Wilhelm I of Prussia became the first German Emperor, also known as Kaiser. It ended when the third Emperor, Wilhelm II, lost power at the end of World War I.

The German Empire was sometimes called the "Second Reich." The word "Reich" can mean empire, kingdom, or state. Many parts of the Empire had been members of the North German Confederation before.

Some Germans used the term "Reich" to describe three different periods in their history. The first was the Holy Roman Empire. The second was the German Empire. The third was Nazi Germany, also known as the "Third Reich."

The term "Second Reich" was made popular by a writer named Arthur Moeller van den Bruck in the 1920s. He wanted to connect the German Empire to the strong Holy Roman Empire of the past. Germany was facing big problems after losing World War I. He hoped a "Third Reich" could unite the country again. Later, the Nazis used these words to make themselves seem powerful.

Contents

How Germany Became an Empire

The Unification of Germany

After the Napoleonic Wars, a group of German states formed the German Confederation in 1815. This was decided at the Congress of Vienna.

Over time, German people wanted to be united. This feeling, called Pan-Germanism, changed from being about freedom to a more practical way of thinking. This new approach was led by Otto von Bismarck, the prime minister of Prussia.

Bismarck wanted Prussia to be the most powerful state in Germany. To do this, he aimed to unite the German states and keep Austria, Prussia's main rival, out of the new German empire. He imagined a strong Germany led by Prussia.

Three Wars Lead to Unification

Three important wars helped Bismarck achieve his goal. These wars showed the German people that unification was possible:

- The Second war of Schleswig against Denmark in 1864.

- The Austro-Prussian War in 1866.

- The Franco-Prussian War against France in 1870–71.

The German Confederation ended after the Austro-Prussian War in 1866. Prussia and its allies fought against the Austrian Empire. After this war, the North German Confederation was formed in 1867. It included 22 states north of the Main River.

The strong national pride that came from winning the Franco-Prussian War convinced the remaining four states south of the Main River to join. In November 1870, they officially joined the North German Confederation.

The Empire's Beginning

Left, on the podium (in black): Crown Prince Frederick (later Frederick III), his father Emperor Wilhelm I, and Frederick I of Baden, proposing a toast to the new emperor.

Centre (in white): Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, Prussian Chief of Staff.

On December 10, 1870, the parliament of the North German Confederation decided to rename itself the "German Empire." They also gave the title of German Emperor to William I, who was the King of Prussia.

The new constitution and the title of Emperor officially began on January 1, 1871. While the Siege of Paris was still happening, William I was officially declared Emperor. This happened on January 18, 1871, in the famous Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.

How the German Empire Was Governed

The German Empire's government was based on a constitution adopted in April 1871. It was very similar to the earlier North German Constitution.

The empire had a parliament called the Reichstag. Men could vote for its members, but the voting districts were old. This meant that rural areas had more power than growing cities.

Laws also needed approval from the Bundesrat. This was a council with representatives from the 27 states. The Emperor, or Kaiser, held the main power. He was helped by a Chancellor. The Chancellor was only answerable to the Emperor.

The Emperor's Power

The Emperor had many important powers. He could appoint and fire the Chancellor. This meant the Emperor really ran the empire through his Chancellor. He was also the supreme commander of the armed forces. The Emperor made all final decisions about foreign affairs. He could even close the Reichstag and call for new elections.

The Chancellor was officially in charge of all state matters. However, other top officials, called State Secretaries, managed different areas like finance or foreign affairs. The Reichstag could pass, change, or reject laws. But in reality, the Emperor and his Chancellor held the most power.

Prussia's Influence

Even though it was a federal empire with many states, Prussia was the most powerful. Prussia covered two-thirds of the new empire and had three-fifths of its people. The Emperor's title was passed down through Prussia's ruling family, the House of Hohenzollern.

Most of the time, the Chancellor was also the prime minister of Prussia. Prussia had 17 out of 58 votes in the Bundesrat. This meant Berlin (the capital of Prussia) only needed a few more votes from smaller states to control things.

The other states kept their own governments. But their power was limited. For example, postage stamps and money were for the whole empire. While states could issue some coins, the military forces of smaller states were controlled by Prussia. Larger states like Bavaria and Saxony had their armies, but they followed Prussian rules and would be controlled by the federal government during wartime.

Democratic Features and Flaws

The German Empire had some democratic parts, even though it was mostly authoritarian. All adult men could vote, and political parties were allowed to grow. Bismarck wanted to create a system that looked democratic but kept power with the rulers.

However, there was a big problem. The voting system in Prussia was very unfair. The richest people could choose 85% of the lawmakers. This almost always guaranteed that conservatives would win. Since the King of Prussia was also the Emperor, this created a conflict. The same rulers had to deal with parliaments elected in very different ways. Also, as cities grew, rural areas had too much power in the Reichstag from the 1890s onwards.

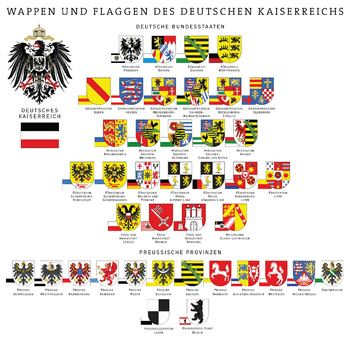

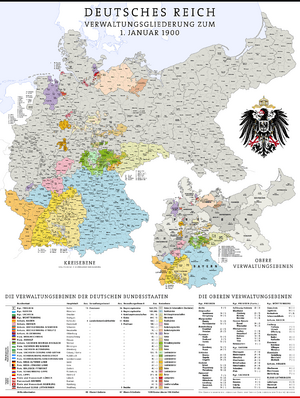

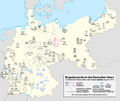

States of the German Empire

Before Germany united, it was made up of 27 different states. These included kingdoms, grand duchies, duchies, principalities, free cities, and one imperial territory. The free cities had a republican government, even though the Empire was a monarchy.

The Kingdom of Prussia was the largest state. It covered two-thirds of the empire's land. Many of these states had been independent for a long time. Some were created after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. States were not always in one piece; some were spread out due to history. Some states, like Hanover, were taken over by Prussia after the 1866 war.

Each state sent representatives to the Federal Council (Bundesrat) and the Imperial Diet (Reichstag). The relationship between the central government and the states changed over time.

| State | Capital | |

|---|---|---|

| Kingdoms (Königreiche) | ||

| Prussia (Preußen) | Berlin | |

| Bavaria (Bayern) | Munich | |

| Saxony (Sachsen) | Dresden | |

| Württemberg | Stuttgart | |

| Grand duchies (Großherzogtümer) | ||

| Baden | Karlsruhe | |

| Hesse (Hessen) | Darmstadt | |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | Schwerin | |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz | Neustrelitz | |

| Oldenburg | Oldenburg | |

| Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) | Weimar | |

| Duchies (Herzogtümer) | ||

| Anhalt | Dessau | |

| Brunswick (Braunschweig) | Braunschweig | |

| Saxe-Altenburg (Sachsen-Altenburg) | Altenburg | |

| Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha) | Coburg | |

| Saxe-Meiningen (Sachsen-Meiningen) | Meiningen | |

| Principalities (Fürstentümer) | ||

| Lippe | Detmold | |

| Reuss, junior line | Gera | |

| Reuss, senior line | Greiz | |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Bückeburg | |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | Rudolstadt | |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | Sondershausen | |

| Waldeck-Pyrmont | Arolsen | |

| Free Hanseatic cities (Freie Hansestädte) | ||

| Bremen | ||

| Hamburg | ||

| Lübeck | ||

| Imperial territory (Reichsland) | ||

| Alsace-Lorraine (Elsaß-Lothringen) | Straßburg | |

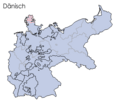

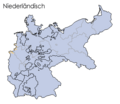

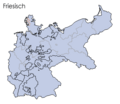

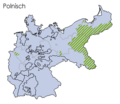

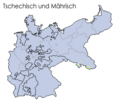

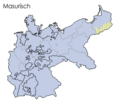

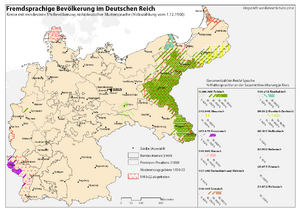

Languages Spoken in the Empire

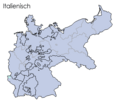

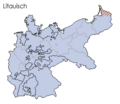

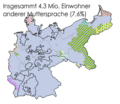

About 92% of the people in the German Empire spoke German as their main language. The largest minority language was Polish, spoken by about 5.4% of the population. This number goes up to over 6% if you include related languages like Kashubian and Masurian.

Other languages like Danish, Dutch, and Frisian were spoken in the north and northwest. These were near the borders with Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Low German was spoken across northern Germany. Even though it's different from High German, it's still considered "German."

Polish and other Slavic languages were mostly spoken in the eastern parts of the empire. A small number of people (0.5%) spoke French, especially in the Alsace-Lorraine region. There, French speakers made up 11.6% of the population.

Language Census Results (1900)

| Language | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| German | 51,883,131 | 92.05 |

| German and a foreign language | 252,918 | 0.45 |

| Polish | 3,086,489 | 5.48 |

| French | 211,679 | 0.38 |

| Masurian | 142,049 | 0.25 |

| Danish | 141,061 | 0.25 |

| Lithuanian | 106,305 | 0.19 |

| Kashubian | 100,213 | 0.18 |

| Wendish (Sorbian) | 93,032 | 0.16 |

| Dutch | 80,361 | 0.14 |

| Italian | 65,930 | 0.12 |

| Moravian (Czech) | 64,382 | 0.11 |

| Czech | 43,016 | 0.08 |

| Frisian | 20,677 | 0.04 |

| English | 20,217 | 0.04 |

| Russian | 9,617 | 0.02 |

| Swedish | 8,998 | 0.02 |

| Hungarian | 8,158 | 0.01 |

| Spanish | 2,059 | 0.00 |

| Portuguese | 479 | 0.00 |

| Other foreign languages | 14,535 | 0.03 |

| Imperial citizens on 1 December 1900 | 56,367,187 | 100 |

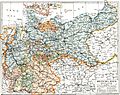

Maps of Languages Spoken

-

Czech (and Moravian)

The Empire's Legacy

The defeat in World War I and the harsh rules of the Treaty of Versailles made many Germans look back fondly on the Empire. They often disliked the new government, the Weimar Republic. People with different political views had their own ideas about the Empire. This led to a lot of political and social disagreements in Germany after the Empire ended.

Under Bismarck, Germany finally became a united country. However, it was still largely controlled by Prussia and did not include German-speaking Austria, which some nationalists wanted. The strong military, efforts to gain colonies, and fast-growing industries made other nations dislike and envy Germany.

The German Empire also brought in some modern changes. It created Europe's first social welfare system, which helped people in need. It also allowed freedom of the press. The system for electing the federal parliament, the Reichstag, was modern, giving every adult man a vote. This allowed groups like the Socialists and the Catholic Centre Party to play important roles, even though Prussian nobles were often against them.

Culture and Economy

The time of the German Empire is remembered for its strong cultural and intellectual growth. Famous writer Thomas Mann published his novel Buddenbrooks in 1901. Theodor Mommsen won the Nobel Prize in Literature a year later for his history of Rome. Artists formed groups like Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke, contributing to modern art. The AEG turbine factory in Berlin, built in 1909, was a key example of modern architecture. This period of growth, called Gründerzeit, is sometimes seen as a golden age.

In economics, the "Kaiserzeit" (Emperor's time) set the stage for Germany to become a leading economic power. Industries like iron and coal in the Ruhr, Saar, and Upper Silesia regions were very important. The first car was built by Karl Benz in 1886. This huge growth in industry led to many people moving to cities. Germany quickly became a nation of city dwellers. More than 5 million Germans moved to the United States during the 19th century.

Related pages

- Germany

- Holy Roman Empire

- Nazi Germany, or "Drittes Reich"

Images for kids

-

A postage stamp from the Caroline Islands

-

The Krupp works in Essen, 1890

-

Frederick III, emperor for only 99 days (9 March – 15 June 1888)

-

Wilhelm II in 1902

-

The Reichstag in the 1890s/early 1900s

-

Bismarck at the Berlin Conference, 1884

-

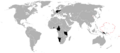

Map of the world showing the participants in World War I. Those fighting on the Entente's side (at one point or another) are depicted in green, the Central Powers in orange, and neutral countries in grey.

See also

In Spanish: Imperio alemán para niños

In Spanish: Imperio alemán para niños