Pan-Germanism facts for kids

Pan-Germanism (which in German is called Pangermanismus or Alldeutsche Bewegung) is a political idea. People who believed in Pan-Germanism wanted to unite all German-speaking people into one big country. This dream country was sometimes called the Greater Germanic Reich.

This idea was very important in German politics during the 1800s, especially when Germany became a united country in 1871. However, Austria was not included in this new Germany. In the late 1800s, many Pan-German thinkers started to believe that their own group was better than others. This led to racist ideas. Later, this thinking influenced Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany to try and bring German-speaking people "home to the Reich" (Heim ins Reich). This was one of the main reasons for World War II.

After World War II, Pan-Germanism was seen as a bad idea in both West and East Germany because of its link to the war. Today, only a few nationalist groups in Germany and Austria still support it.

Contents

What Does "Pan-Germanism" Mean?

The word "pan" comes from ancient Greek and means "all," "every," or "whole." So, "Pan-Germanism" means "all Germans." The word "German" comes from the Latin word "Germani," which Julius Caesar used to describe tribes in northeastern Gaul.

Later, in the Middle Ages, "German" came to mean people who spoke Germanic languages, which are the ancestors of modern German. The term "Pan-German" was first used in English in 1892. In German, a similar idea is called alldeutsch, which means "all German." This term refers to the political goal of uniting all German-speaking people in one country.

How Pan-Germanism Started (Before 1860)

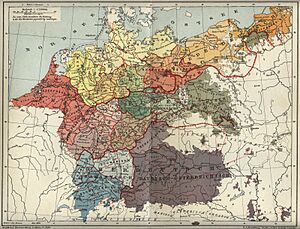

The idea of Pan-Germanism began during the Napoleonic Wars in the early 1800s. People like Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Ernst Moritz Arndt were early supporters. For a long time, Germans were not united. After the Thirty Years' War (a big war in the 1600s), the Holy Roman Empire broke into many small states.

People who supported the "Greater Germany" (Großdeutschland) idea wanted to unite all German-speaking people in Europe. They hoped the Austrian Empire would lead this new country. This idea was popular among revolutionaries in 1848, including famous people like Richard Wagner. Some writers also believed that Germans should lead Central and Eastern Europe. They saw this as a "push to the East" (Drang nach Osten), where Germans would naturally move eastward to live and reunite with German minorities there. They called this "living space" (Lebensraum).

The German national anthem, "Deutschlandlied," written in 1841, talks about Germany stretching from the Meuse River to the Memel River, and from the Adige River to the Belt. This shows how big some people imagined Germany could be.

The German Question: Uniting Germany

By the 1860s, Prussia and Austria were the two most powerful states with German-speaking leaders. Both wanted to expand their power. Austria was a country with many different ethnic groups, not just Germans.

Under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, Prussia united most of the northern German lands. In 1866, Bismarck excluded Austria from this new Germany after a war. Then, in 1871, the German Empire was formed with the Prussian king, Wilhelm I, as its leader. This new Germany did not include Austria or its German-speaking people.

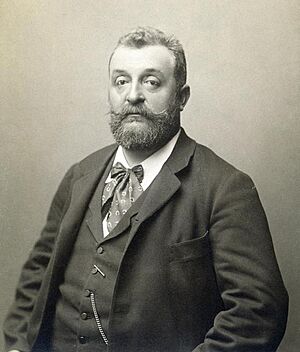

Even though Austria was left out, many people in both Austria and Germany still wanted to unite German Austrians with Germany. In Austria-Hungary, radical Pan-Germanists like Georg Schönerer wanted all German-speaking parts of the Habsburg monarchy to join the German Empire. Schönerer's ideas, which included strong German nationalism and racism, later influenced Adolf Hitler and his Nazi ideology.

In 1891, the Pan-German League was formed. This group was very nationalistic and supported expanding German power. It also promoted antisemitism, which is hatred towards Jewish people. This group was popular among educated middle and upper-class people. They wanted to make Germans living outside Germany feel more connected to their homeland.

During World War I, some German leaders, like Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, had plans for Germany to take over more land, similar to what Pan-German nationalists wanted.

Pan-Germanism in Austria

After the revolutions of 1848, when many people wanted a "Greater Germany," Austria lost a war against Prussia in 1866. This meant Austria was left out of the new German state. Because of this, and growing conflicts between different ethnic groups in Austria, a German nationalist movement grew in Austria.

This movement was led by Georg Ritter von Schönerer. His groups wanted all German-speaking parts of the Habsburg monarchy to join the German Empire. They did not want Austrians to have their own separate identity. Schönerer's strong German nationalism and racist ideas were a big influence on Adolf Hitler and his Nazi beliefs.

In 1933, Austrian Nazis and other nationalist groups worked together against the Austrian government. They wanted Austria to join Germany. In 1938, Austria was indeed joined with Nazi Germany in an event called the "Anschluss." This was the historical goal of Austrian German nationalists.

After World War II ended in 1945, the ideas of Pan-Germanism and the "Anschluss" became very unpopular because they were so closely linked to Nazism. This allowed Austrians to develop their own national identity.

Some people also thought about including German-speaking Scandinavians (like Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes) in a Pan-German state. For example, Jacob Grimm believed that the Jutland peninsula (part of Denmark) had been settled by Germans before the Danes arrived, and so Germany could claim it. He also thought the rest of Denmark should join Sweden.

However, this idea was strongly opposed by people like Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, an archaeologist. He argued that there was no way to know the language of the earliest people in Denmark. He also pointed out that if Germany could claim land based on old history, then Slavs could claim parts of Eastern Germany.

Despite these arguments, Pan-Germanism encouraged German nationalists in Schleswig and Holstein, leading to a war in 1848. This also meant that Pan-Germanism never became very popular in Denmark, but it did gain some support in Norway, especially among those who wanted Norway to be independent. Some famous Norwegian supporters included Knut Hamsun and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. Bjørnson, who wrote the Norwegian national anthem, said in 1901 that he dreamed of all Germanic peoples uniting in a confederation.

In the 1900s, the German Nazi Party wanted to create a "Greater Germanic Reich" that would include most Germanic peoples in Europe, like Danes, Dutch, Swedes, Norwegians, and Flemish people. However, anti-German feelings grew in Denmark in the 1930s and 1940s because of Nazi Germany's Pan-German ambitions.

Pan-Germanism from 1918 to 1945

World War I was the first time people tried to put Pan-German ideas into practice. After Germany lost World War I, its power in Central and Eastern Europe was greatly reduced. The Treaty of Versailles made Germany much smaller. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up. A smaller Austria, mostly German-speaking, wanted to unite with Germany and even called itself "German Austria." However, the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1919 forbade this union, and Austria had to change its name back.

It was in the Weimar Republic (Germany after WWI) that Adolf Hitler, who was born in Austria, first developed his German nationalist ideas. He wrote about them in his book Mein Kampf. Hitler and his followers shared many of the Pan-German goals, but they had different political styles. Hitler's party, the Nazi Party, eventually became very powerful.

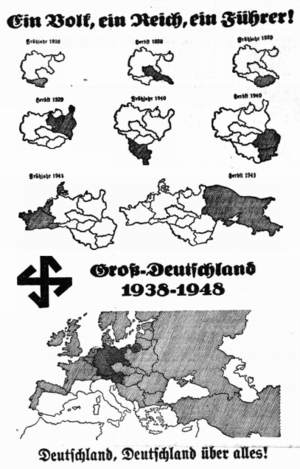

Nazi propaganda used the slogan "Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer" ("One people, one Reich, one leader") to encourage Pan-German feelings in Austria and support the "Anschluss" (union with Germany).

The Nazis wanted their new empire to be like the old Holy Roman Empire from the Middle Ages, which they called the "First Reich." Hitler admired the old emperors but criticized them for not focusing enough on expanding eastward. After the "Anschluss," Hitler moved the old imperial jewels from Vienna to Nuremberg. This was to show that Nazi Germany was the true successor to the old empire and to weaken Vienna's importance.

After Germany took over parts of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Hitler said the Holy Roman Empire had been "resurrected." However, he wanted his empire to be different: racist and nationalist, not like the "internationalist Catholic empire" of the past. He saw it as a step forward to a "new golden age."

The Nazis also used the historical borders of the Holy Roman Empire to claim modern territories. They wanted to undo the Peace of Westphalia from 1648, which had given many small states independence.

The "Heim ins Reich" ("Back Home to the Reich") policy was how the Nazis tried to convince ethnic Germans living outside Germany to join the "Greater Germany." This idea led to an even bigger vision: the "Greater Germanic Reich." This huge empire was meant to include almost all of Germanic Europe, such as the Netherlands, Belgium, parts of France, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and German-speaking parts of Switzerland. The main exception was the United Kingdom, which the Nazis hoped would become an ally.

The Nazis also planned to take over vast areas of Ukraine and Russia, seeing them as vital for "living space" (Lebensraum). They called this a "pull towards the East" (Drang nach Osten). They openly copied the American idea of "Manifest Destiny" and expanding into new lands.

As World War II continued, some leaders in the Waffen-SS (a Nazi military group) started to think about a European union of self-governing states, led by Germany, to fight against communism. However, Heinrich Himmler, a top Nazi leader, still held onto his Pan-German vision. He told his officers that they should put the idea of a "greater racial and historical ideal" – the Germanic Reich – above their own national ideals.

Pan-Germanism After 1945

The defeat of Germany in World War II led to the decline of Pan-Germanism. Germany itself was badly damaged and divided into West and East Germany. Austria was separated from Germany, and the idea of a German identity in Austria also weakened. Germany lost even more land in the east after World War II.

Pan-Germanism became a forbidden topic because it was so strongly linked to the Nazis' racist ideas of a "master race." However, when Germany was reunited in 1990, some old discussions about German identity came up again.

See also

In Spanish: Pangermanismo para niños

In Spanish: Pangermanismo para niños

|

History and Ideas |

1800s and 1900s

|

World War II Era

|

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |