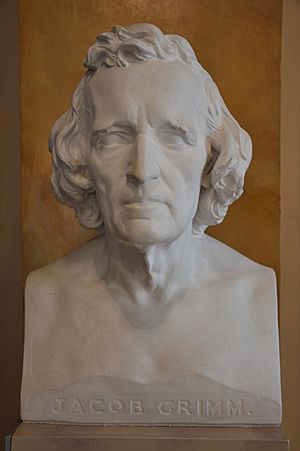

Jacob Grimm facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacob Grimm

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm

4 January 1785 Hanau, Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 20 September 1863 (aged 78) |

| Parent(s) | Philipp Grimm (father) Dorothea Grimm (mother) |

| Relatives | Wilhelm Grimm (brother) Ludwig Emil Grimm (brother) Herman Grimm (nephew) Ludwig Hassenpflug (brother-in-law) |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Marburg |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions | University of Göttingen University of Berlin |

| Notable students | Wilhelm Dilthey |

| Influenced | August Schleicher |

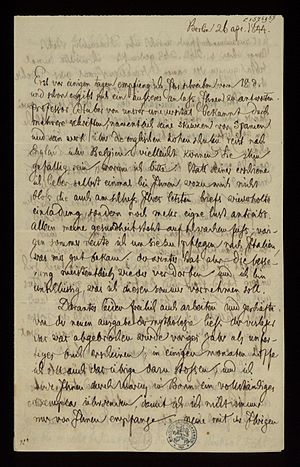

| Signature | |

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (born January 4, 1785 – died September 20, 1863) was a famous German author, linguist, and folklorist. He is best known for discovering Grimm's law in linguistics and for co-writing the huge Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary). Jacob also wrote Deutsche Mythologie (German Mythology) and edited Grimms' Fairy Tales. He was the older brother of Wilhelm Grimm. Together, they were known as the famous Brothers Grimm.

Contents

Jacob Grimm's Life and Work

Jacob Grimm was born in Hanau, Germany, on January 4, 1785. His father, Philipp Grimm, was a lawyer. Sadly, his father died when Jacob was a child. This left his mother, Dorothea, with very little money. Luckily, her sister helped the family. She was a lady-in-waiting to the Landgravine of Hesse, which meant she worked for a noblewoman. This help allowed Jacob and his younger brother, Wilhelm Grimm, to go to school in Kassel in 1798.

In 1802, Jacob went to the University of Marburg to study law. This was the career his father had planned for him. His brother Wilhelm joined him a year later, also studying law after recovering from a serious illness.

How Jacob Grimm Became Interested in History

At the university, Jacob Grimm was greatly inspired by the lectures of Friedrich Carl von Savigny. Savigny was an expert in Roman law. Wilhelm Grimm later said that Savigny helped them understand science better. Savigny's lessons also made Jacob love studying history and old things.

It was in Savigny's library that Jacob first saw old German writings. These texts made him want to learn more about the language they were written in.

In 1805, Savigny invited Jacob to Paris to help him with his writing. There, Jacob became even more interested in literature from the Middle Ages. Later that year, he returned to Kassel, where his mother and brother were living.

The next year, Jacob got a job in the war office. He didn't earn much, but the job gave him plenty of free time for his studies. He joked that he had to trade his fancy Paris suit for a stiff uniform!

Working as a Librarian

In 1808, after his mother passed away, Jacob became the superintendent of the private library for King Jérôme Bonaparte. This king ruled the Kingdom of Westphalia, which included Jacob's home of Hesse-Kassel. Jacob also became an auditor for the state council, but his main job was still at the library. His salary increased, and his official duties were easy.

In 1813, after Napoleon's rule ended, Jacob was appointed Secretary of Legation. This meant he traveled with the Hessian minister to the allied army's headquarters. In 1814, he went to Paris to get back books that the French had taken. He also attended the Congress of Vienna, an important meeting of European leaders.

When he returned, he was sent to Paris again for more book returns. Meanwhile, Wilhelm got a job at the Kassel library. In 1816, Jacob became the second librarian there. In 1828, the head librarian died. Both brothers hoped to be promoted, but the job went to someone else.

Because they were unhappy, Jacob and Wilhelm moved to the University of Göttingen in 1829. Jacob became a professor and librarian, and Wilhelm became an under-librarian. Jacob taught about old legal traditions, how languages change over time, and the history of literature. He also explained old German poems.

Later Years and Important Work

Jacob Grimm joined a group of professors known as the Göttingen Seven. They protested against the King of Hanover because he canceled a fair constitution. As a result, Jacob lost his job and was sent away from Hanover in 1837. His brother Wilhelm, who also signed the protest, returned to Kassel with him.

They stayed in Kassel until 1840. Then, King Frederick William IV of Prussia invited them to the University of Berlin. Both brothers became professors and members of the Academy of Sciences. Jacob didn't have to teach much, so he spent his time working with Wilhelm on their huge dictionary project.

Jacob Grimm continued to work until he died in Berlin at the age of 78.

Jacob Grimm's Work on Language

History of the German Language

Jacob Grimm's book, Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (History of the German Language), looked at German history through its words. It was the first book to study the linguistic history of the early Germanic tribes. He gathered old words and hints from ancient writings. He tried to figure out how German was related to other languages that were only known through Greek and Latin texts.

While some of his ideas were later changed, his book had a huge impact. It helped people understand how languages develop over time.

German Grammar

Grimm's famous Deutsche Grammatik (German Grammar) was a major work in language study. He used many old texts, dictionaries, and grammars to create it. He wanted to compare different Germanic languages.

The first part of his Grammar came out in 1819. It looked at how words change form in many Germanic languages. He also wrote an introduction explaining why studying the history of the German language was important.

In 1822, a second edition of the book was published. This was almost a completely new work. More than half of the second volume focused on how sounds change in languages. Grimm realized that understanding how sounds change was key to studying languages. This idea made his research very strong and consistent.

His progress was greatly influenced by Rasmus Rask, a Danish linguist. Rask's grammar helped Grimm understand Old English better. Rask was also the first to clearly explain how sounds matched up in different languages.

The Grammar continued with three more volumes, covering word formation and sentence structure. Grimm started a third edition, but only one part was finished. He then focused on the dictionary. The Grammar is known for being very detailed and thorough. It became a model for future language researchers.

Grimm's Law: How Sounds Change

Jacob Grimm is famous for explaining Grimm's law. This law describes how certain consonant sounds changed over time in Germanic languages. It was first noticed by Rasmus Rask. Grimm's law was a big step in linguistics because it showed a clear, scientific way to study how languages change.

The law explains how consonants in the ancient Proto-Indo-European language changed into the sounds we hear in Germanic languages like English and German. Grimm fully explained this law in the second edition of his Grammar. While others had noticed some sound changes, Grimm made it a complete and widespread rule. He also extended the law to include High German, which was entirely his own work.

The German Dictionary

Jacob Grimm's massive dictionary of the German Language, called the Deutsches Wörterbuch, began in 1838. The first part was published in 1854. The Brothers Grimm thought it would take 10 years and fill about six or seven volumes. However, it was such a huge project that they couldn't finish it themselves.

The dictionary, as far as Jacob Grimm worked on it, was a collection of valuable essays about old German words. Other scholars finally finished the dictionary in 1961. It was updated in 1971. With 33 volumes and around 330,000 main words, it is still an important reference book today. A project is currently underway to update the dictionary to modern standards.

Jacob Grimm's Literary Work

Jacob Grimm's first published work, Über den altdeutschen Meistergesang (1811), was about literature. In this essay, he showed that two types of old German poetry, Minnesang and Meistergesang, were actually different stages of the same poetic form. He also discovered that old German songs usually had three parts.

Many of Jacob's text editions were done with his brother Wilhelm. In 1812, they published two old fragments: the Hildebrandslied and the Weißenbrunner Gebet. Jacob found that these poems used alliteration, a poetic device where words close together start with the same sound. However, Jacob didn't really enjoy editing texts. He preferred to leave that to others.

Both brothers loved national poetry, including epics, ballads, and folk tales. In 1816–1818, they published Deutsche Sagen (German Legends), a collection of stories from different sources. At the same time, they gathered all the folk tales they could find, some from people telling stories and some from old writings. In 1812–1815, they published the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children's and Household Tales). These fairy tales made the Brothers Grimm famous around the world.

Jacob Grimm was also interested in the funny animal stories from the Middle Ages, called beast epics. He published an edition of Reinhart Fuchs in 1834. His first contribution to mythology was the first volume of an edition of the Eddaic songs, which he worked on with his brother in 1815.

His most famous work on mythology, Deutsche Mythologie (German Mythology), came out in 1835. This book explored the myths and superstitions of the old Germanic people. It traced their beliefs from ancient times to modern-day traditions, tales, and sayings.

Jacob Grimm's Legal Studies

Jacob Grimm's work as a lawyer was very important for understanding the history of law, especially in Northern Europe.

His essay Von der Poesie im Recht (Poetry in Law, 1816) explored a deep, romantic idea of law. His Deutsche Rechtsaltertümer (German Legal Antiquities, 1828) was a huge collection of legal sources from all Germanic languages. This book helped people understand older German legal traditions that were not influenced by Roman law. Grimm's Weisthümer (4 volumes, 1840–63) collected oral legal traditions from rural Germany. This work helps researchers study how written law developed in Northern Europe.

Jacob Grimm and Politics

|

Jacob Grimm

MdFN

|

|

|---|---|

| Member of the Frankfurt Parliament for Kreis Duisburg |

|

| In office 24 May 1848 – 2 October 1848 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Carl Schorn |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Casino |

Jacob Grimm's work was closely connected to his ideas about Germany and its culture. His studies of fairy tales and language origins were about the country's roots. He wanted Germany to be united. Like his brother, he supported the Liberal movement, which wanted a constitutional monarchy (a king or queen with limited power) and civil liberties (freedoms for citizens). Their involvement in the Göttingen Seven protest showed this.

During the German revolution of 1848, Jacob Grimm was elected to the Frankfurt Parliament. This Parliament was formed by elected members from different German states to create a constitution for Germany. Grimm was chosen partly because he stood up to the King of Hanover. In Frankfurt, he gave speeches and insisted that the German-speaking duchy of Holstein, which was ruled by Denmark, should be part of Germany.

However, Grimm soon became disappointed with the National Assembly. He asked to be released from his duties so he could go back to his studies.

Death

Jacob Grimm died on September 20, 1863, in Berlin, Germany. He was 78 years old and worked until the very end of his life.

Works by Jacob Grimm

The following is a list of books and works published by Jacob Grimm. Those he published with his brother Wilhelm are marked with a star (*).

- Über den altdeutschen Meistergesang (Göttingen, 1811)

- *Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Berlin, 1812–1815) (many editions)

- *Das Lied von Hildebrand und des Weissenbrunner Gebet (Kassel, 1812)

- Altdeutsche Wälder (Kassel, Frankfurt, 1813–1816, 3 vols.)

- *Der arme Heinrich von Hartmann von der Aue (Berlin, 1815)

- Irmenstrasse und Irmensäule (Vienna, 1815)

- *Die Lieder der alten Edda (Berlin, 1815)

- Silva de romances viejos (Vienna, 1815)

- *Deutsche Sagen (Berlin, 1816–1818, 2nd ed., Berlin, 1865–1866)

- Deutsche Grammatik (Göttingen, 1819, 2nd ed., Göttingen, 1822–1840) (reprinted 1870 by Wilhelm Scherer, Berlin)

- Wuk Stephanowitsch' Kleine Serbische Grammatik, verdeutscht mit einer Vorrede (Leipzig and Berlin, 1824)

- Zur Recension der deutschen Grammatik (Kassel, 1826)

- *Irische Elfenmärchen, aus dem Englischen (Leipzig, 1826)

- Deutsche Rechtsaltertümer (Göttingen, 1828, 2nd ed., 1854)

- Hymnorum veteris ecclesiae XXVI. interpretatio theodisca (Göttingen, 1830)

- Reinhart Fuchs (Berlin, 1834)

- Deutsche Mythologie (Göttingen, 1835, 3rd ed., 1854, 2 vols.)

- Taciti Germania edidit (Göttingen, 1835)

- Über meine Entlassung (Basel, 1838)

- (together with Schmeller) Lateinische Gedichte des X. und XI. Jahrhunderts (Göttingen, 1838)

- Sendschreiben an Karl Lachmann über Reinhart Fuchs (Berlin, 1840)

- Weistümer, Th. i. (Göttingen, 1840) (continued, partly by others, in 5 parts, 1840–1869)

- Andreas und Elene (Kassel, 1840)

- Frau Aventure (Berlin, 1842)

- Geschichte der deutschen Sprache (Leipzig, 1848, 3rd ed., 1868, 2 vols.)

- Des Wort des Besitzes (Berlin, 1850)

- *Deutsches Wörterbuch, Bd. i. (Leipzig, 1854)

- Rede auf Wilhelm Grimm und Rede über das Alter (Berlin, 1868, 3rd ad., 1865)

- Kleinere Schriften (F. Dümmler, Berlin, 1864–1884, 7 vols.).

- vol. 1 : Reden und Abhandlungen (1864, 2nd ed. 1879)

- vol. 2 : Abhandlungen zur Mythologie und Sittenkunde (1865)

- vol. 3 : Abhandlungen zur Litteratur und Grammatik (1866)

- vol. 4 : Recensionen und vermischte Aufsätze, part I (1869)

- vol. 5 : Recensionen und vermischte Aufsätze, part II (1871)

- vol. 6 : Recensionen und vermischte Aufsätze, part III

- vol. 7 : Recensionen und vermischte Aufsätze, part IV (1884)

See also

In Spanish: Jacob Grimm para niños

In Spanish: Jacob Grimm para niños