Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson

|

|

|---|---|

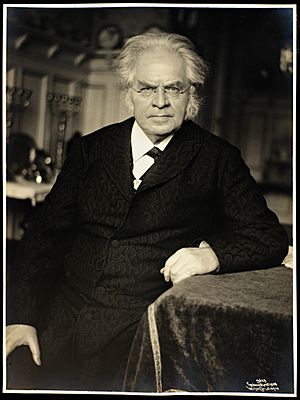

Bjørnson in 1909

|

|

| Born | 8 December 1832 Kvikne, Norway |

| Died | 26 April 1910 (aged 77) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, playwright, lyricist |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1903 |

| Spouse | Karoline Reimers |

| Children | Bjørn Bjørnson, Bergljot Ibsen, Erling Bjørnson |

| Relatives | Peder Bjørnson (father), Elise Nordraak (mother), Maria Björnson (great-granddaughter) |

| Signature | |

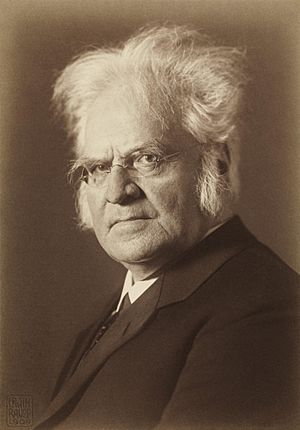

Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson (8 December 1832 – 26 April 1910) was a famous Norwegian writer. He won the 1903 Nobel Prize in Literature for his "noble, magnificent and versatile poetry." He was the first Norwegian to win a Nobel Prize.

Bjørnson wrote many strong opinions and was very important in Norway's public life. He also influenced cultural discussions in Scandinavia. He is seen as one of the four great Norwegian writers, along with Ibsen, Lie, and Kielland. He is also known for writing the words to Norway's national anthem, "Ja, vi elsker dette landet".

Contents

Early Life and School

Bjørnson was born on a farm called Bjørgan in Kvikne. This was a quiet village in the Østerdalen area, about sixty miles south of Trondheim. In 1837, Bjørnson's father, Peder Bjørnson, who was a priest in Kvikne, moved to a new church in Nesset. This was near Molde in Romsdal. Bjørnson spent his childhood in this beautiful area, living at the Nesset Parsonage.

After studying for a few years in the nearby city of Molde, Bjørnson was sent to Heltberg Latin School in Christiania at age 17. He went there to get ready for university. This school also taught other famous writers like Ibsen, Lie, and Vinje.

Bjørnson knew he wanted to be a poet, as he had been writing poems since he was eleven. He started studying at the University of Oslo in 1852. Soon after, he began working as a journalist, mostly writing reviews about plays.

First Works

In 1857, Bjørnson published Synnøve Solbakken. This was the first of his "peasant novels." These stories were about the lives of farmers and people in the countryside. In 1858, he wrote Arne, followed by En glad Gut (A Happy Boy) in 1860, and Fiskerjentene (The Fisher Girls) in 1868. These are some of his most important peasant tales.

Bjørnson wanted to "create a new saga in the light of the peasant." He believed this should be done not just in novels, but also in national plays or folke-stykker. His first play was Mellem Slagene (Between the Battles), written in 1855. It was performed in 1857. He was inspired by writers like Jens Immanuel Baggesen and Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger during a visit to Copenhagen. After Mellem Slagene, he wrote Halte-Hulda (Lame Hulda) in 1858 and Kong Sverre (King Sverre) in 1861. His most important work from this time was the three-part poetic story Sigurd Slembe, published in 1862.

Later Career

At the end of 1857, Bjørnson became the director of the theater in Bergen. He held this job for two years before returning to Christiania. From 1860 to 1863, he traveled a lot around Europe. In early 1865, he took over the management of the Christiania Theatre. There, he put on his popular comedy De Nygifte (The Newly Married) and his romantic tragedy about Mary Stuart. In 1870, he published Poems and Songs and the long poem Arnljot Gelline. This book included the ode Bergliot, which is one of his best lyrical poems.

Between 1864 and 1874, Bjørnson was less focused on writing. He spent most of his time on politics and managing the theater. During this time, he gave many strong speeches as a supporter of big changes. In 1871, he also started giving talks across Scandinavia.

From 1874 to 1876, Bjørnson was away from Norway. In this peaceful time away, he got his creative energy back. He started writing plays again with En fallit (A Bankruptcy) and Redaktøren (The Editor) in 1874. These were realistic plays about society that were very modern for their time.

Working with Edvard Grieg

In the 1870s, Bjørnson became friends with the composer Edvard Grieg. They both cared about Norway governing itself. Grieg put many of Bjørnson's poems to music, like Landkjenning and Sigurd Jorsalfar. They planned to create an opera based on King Olav Trygvason. However, they disagreed about whether the music or the words should be written first. This led Grieg to work on music for Henrik Ibsen's play Peer Gynt instead, which made Bjørnson upset. Later, their friendship became strong again.

The "National Poet"

Bjørnson settled at his home, Aulestad, in Gausdal. In 1877, he published another novel, Magnhild. In this book, his ideas about social issues were developing. He also showed his ideas about a republic (where people elect their leaders) in his play Kongen (The King). In a later version of the play, he added an essay about "Intellectual Freedom" to explain his views more. Kaptejn Mansana (Captain Mansana), a story about the war for Italian independence, was written in 1878.

Bjørnson really wanted his plays to be successful on stage. So, he focused on a play about social life called Leonarda (1879), which caused a lot of discussion. A play that made fun of things, Det nye System (The New System), came out a few weeks later. Even though people talked a lot about these plays, not many of them made much money.

In 1883, Bjørnson wrote a social play called En Handske (A Gauntlet). But he could not find any theater manager to put it on unless he changed it. In the autumn of the same year, Bjørnson published a play with deep, hidden meanings called Over Ævne (Beyond Powers). This play showed strong religious feelings with great power. It was not performed until 1899, when it became very successful.

Political Views

From a young age, Bjørnson looked up to Henrik Wergeland. He became a strong voice for the Norwegian Left-wing movement. He supported Ivar Aasen and joined political fights in the 1860s and 1870s. When a large monument to Henrik Wergeland was to be built in 1881, there was a political disagreement between the left and right sides. The left side won. Bjørnson gave a speech honoring Wergeland, the constitution, and farmers.

Because of his political views, Bjørnson was accused of treason. He found safety for a while in Germany and returned to Norway in 1882. Believing that theaters were mostly closed to his plays, he went back to writing novels. In 1884, he published Det flager i Byen og paa Havnen (Flags are Flying in Town and Port). This book included his ideas about how traits are passed down and about education. In 1889, he published another long and important novel, Paa Guds veje (On God's Path), which dealt with similar topics. The same year, he published a comedy, Geografi og Kærlighed (Geography and Love), which was successful.

A collection of short stories, which taught lessons and dealt with strong emotional experiences, was published in 1894. Later plays included a political tragedy called Paul Lange og Tora Parsberg (1898), a second part of Over Ævne (Beyond Powers II) (1895), Laboremus (1901), På Storhove (At Storhove) (1902), and Daglannet (Dag's Farm) (1904). In 1899, at the opening of the National Theatre in Oslo, Bjørnson received a big cheer. His historical play about King Sigurd the Crusader was performed at the opening.

Bjørnson was one of the writers for the magazine Ringeren, which was against the union with Sweden. Sigurd Ibsen edited this magazine in 1898.

He was very interested in the idea of bondemaal, which was about creating a national language for Norway. This language would be different from the dansk-norsk (Dano-Norwegian) that most Norwegian literature was written in. Early on, before 1860, Bjørnson tried writing at least one short story in landsmål. However, he soon stopped this effort. He later said he regretted not mastering this language. Bjørnson's strong love for his country did not stop him from seeing what he thought was a big mistake in this language idea. His talks and writings against the extreme form of the målstræv (language movement) were very effective.

His view on this must have changed after 1881, as he still spoke for farmers then. Even though he seemed to support Ivar Aasen and was friendly towards farmers in his novels, he later changed his mind. In 1899, he said there were limits to how much a farmer could improve themselves. "I can draw a line on the wall. The farmer can cultivate himself to this level, and no more," he wrote in 1899. It is rumored that a farmer once insulted him, and he said this in anger. In 1881, he spoke about the farmer's clothes worn by Henrik Wergeland. He said then that this clothing, worn by Wergeland, was "one of the most influential things" in starting the national day. Bjørnson's feelings about farmers remained unclear. His own father was a farmer's son.

During the last twenty years of his life, he wrote hundreds of articles in major European newspapers. He spoke out against the French justice system in the Dreyfus Affair. He also fought for the rights of children in Slovakia to learn their own language. Bjørnson wrote in several newspapers about the Černová massacre. He called it "The greatest industry of Hungary – which was supposedly 'to produce Magyars'."

Later Years

From the start of the Dreyfus Affair, Bjørnson strongly supported Alfred Dreyfus. A person from that time said Bjørnson wrote "article after article in the papers and proclaimed in every manner his belief in his innocence."

Bjørnson was one of the first members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. This committee gives out the Nobel Peace Prize. He was a member from 1901 to 1906. In 1903, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 1901, Bjørnson said, "I'm a Pan-Germanist, I'm a Teuton. My biggest dream is for the South Germanic peoples and the North Germanic peoples and their relatives far away to join together in a friendly group."

Bjørnson had done a lot to make Norwegians feel proud of their country. But in 1903, when Norway and Sweden were about to split, he told Norwegians to be calm and find a peaceful solution. However, in 1905, he mostly stayed quiet.

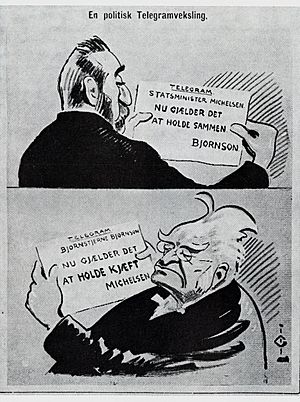

When Norway was trying to end its forced union with Sweden, Bjørnson sent a message to the Norwegian Prime Minister. He said, "Now is the time to unite." The minister supposedly replied, "Now is the time to shut up."

This was actually a funny drawing published in a magazine called Vikingen. But the story became so popular that Bjørnson had to say it wasn't true. He claimed that "Michelsen has never asked me to shut up; it would not help if he did."

Bjørnson died on 26 April 1910 in Paris, where he had spent his winters for some years. He was buried in Norway with great honors. The Norwegian warship HNoMS Norge was sent to bring his body back home.

Bjørnson's Family

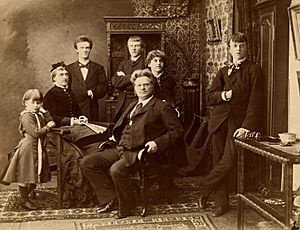

Bjørnson was the son of Reverend Peder Bjørnson and Inger Elise Nordraach. He married Karoline Reimers (1835–1934) in 1858. They had six children, and five of them lived to be adults:

- Bjørn Bjørnson (1859–1942)

- Einar Bjørnson (1864–1942)

- Erling Bjørnson (1868–1959)

- Bergliot Bjørnson (1869–1953)

- Dagny Bjørnson (1871–1872)

- Dagny Bjørnson (1876–1974)

Karoline Bjørnson stayed at Aulestad until she passed away in 1934.

When he was in his early fifties, Bjørnson had a son named Anders Underdal (1880–1973) with Guri Andersdotter (d. 1949). Anders was the father of the Norwegian-Swedish writer Margit Sandemo.

See also

In Spanish: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson para niños

In Spanish: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |