Sverre of Norway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sverre Sigurdsson |

|

|---|---|

Contemporary bust of Sverre from the Nidaros Cathedral, dated c. 1200.

|

|

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | 1177 (claimed) /1184 (undisputed) – 9 March 1202 |

| Coronation | 29 June 1194, Bergen |

| Predecessor | Magnus V |

| Successor | Haakon III |

| Born | c. 1145/1151 |

| Died | 9 March 1202 Bergen, Kingdom of Norway |

| Burial | Old Cathedral, Bergen (destroyed in 1531) |

| Spouse | Margaret of Sweden |

| Issue | Christina of Norway Sigurd Lavard Haakon III of Norway |

| House | Sverre |

| Father | Unås Sigurd II of Norway (claimed; dubious) |

| Mother | Gunnhild |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, excommunicated from AD1194, the King's dominions and Kingdom under Interdictum since AD1198, until his death, yet maintaining communion with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (cf. Communion of the cults of Saint Olav and Saint Valdemar). |

Sverre Sigurdsson (Old Norse: Sverrir Sigurðarson) was the king of Norway from 1184 to 1202. He was born around 1145 or 1151 and died on March 9, 1202. Many people think he was one of the most important rulers in Norwegian history.

Sverre became the leader of a rebel group called the Birkebeiners in 1177. They were fighting against King Magnus Erlingsson. After King Magnus died in the Battle of Fimreite in 1184, Sverre became the only king of Norway. But he had problems with the Church, and they removed him from the Church in 1194. This started another civil war against a group called the Baglers, who were supported by the Church. This war continued even after Sverre died in 1202.

The main historical book about Sverre's life is his biography, the Sverris saga. Parts of this book were written while Sverre was still alive. This saga might be a bit biased because the introduction says Sverre helped pay for it. Letters between the pope and Norwegian bishops also tell us about the Church's side of the story. The saga and the letters mostly agree on the main events.

People said King Sverre was short. He often led his troops from horseback during battles. This was different from the usual Norse warrior style, where kings were expected to fight at the front. Sverre was very good at thinking on his feet, both in politics and in war. His new tactics often helped the Birkebeiners win against enemies who used older ways of fighting. In battles, he had his men fight in smaller groups. Before, armies often used a big "shield wall" formation. Sverre's new way made the Birkebeiners faster and more flexible.

Contents

Early Life of Sverre

According to the saga, Sverre was born in 1151. His mother was Gunnhild, and his father was Unås, a comb maker from the Faroes. When Sverre was five, his family moved to the Faroes. He grew up with his uncle, Roe, who was the bishop of the Faroes. Sverre studied to become a priest there and was ordained. The priest school in Kirkjubøur must have been very good, because Sverre was later known for being well educated. There's a legend that he hid in a cave near the village. This cave really exists and gave the mountain Sverrihola its name.

However, Sverre didn't feel like a priest. The saga says he had dreams that he believed meant he was meant for bigger things. In 1175, his mother told him that he was actually the son of King Sigurd Munn. The next year, Sverre traveled to Norway to find his true path.

Who Was His Father?

The story in Sverre's saga is the official version. Historians have wondered if it's completely true, especially about Sverre being King Sigurd's son. Some historians think his claim was false, just like many people at the time did. Others believe he was truly the king's son. Most historians agree that we can't be sure about his father.

It was common for kings to have sons outside of marriage. But other facts suggest Sverre was in his early thirties when he came to Norway. For example, his own sons and nephews were already quite old. Some people argued that if Sverre was 30 when he became a priest, he couldn't have been born after 1145. King Sigurd Munn was born in 1133, so this would make Sverre's claim impossible. However, this rule about age for priests was often ignored in Scandinavia back then.

Still, Sverre always refused to do a "trial by fire" to prove his claim. This was a common way for new people claiming the throne to show they were telling the truth. Most people believed in it, but Sverre said no. If his claim was false, he wouldn't have a strong right to be king. But his goal was clear: he wanted to be king of Norway, whether he had royal blood or not. Other kings, like Harald Gille, had also become king with questionable family ties.

Norway in 1176

In 1176, Norway was slowly getting better after many years of civil wars. These wars happened mostly because there were no clear rules about who should become king next. According to old customs, all the king's sons, whether born in or out of marriage, had an equal right to the throne. Brothers often ruled together, but arguments often led to war.

Sigurd Munn, who Sverre claimed was his father, was killed by his brother Inge Krokrygg in 1155. Sigurd's son Håkon Herdebrei was chosen as king by his father's followers. The fight became a regional one. King Inge had strong support in Viken, while most of Håkon's followers were from Trøndelag. Inge Krokrygg died in 1161. His group then chose five-year-old Magnus Erlingsson as king. Magnus was the son of Erling Skakke and Kristin, who was the daughter of King Sigurd the Crusader. In 1162, at the Battle of Veøy, Håkon Herdebrei died, and his group started to fall apart. In 1164, Archbishop Øystein Erlendsson crowned Magnus. With the Church and most of the important families on his side, Magnus seemed safe as king. Several small rebellions happened, but they were all stopped. Erling Skakke was the main ruler while his son Magnus was young, and he continued to be the real power even after Magnus grew up.

Sverre Meets the Birkebeiners

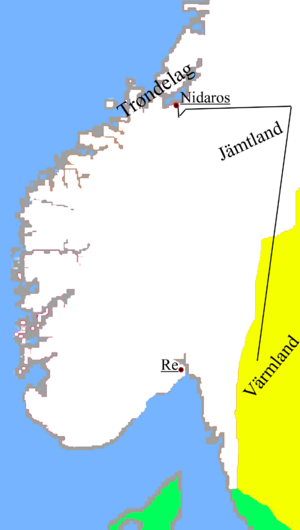

So, when Sverre came to Norway, it seemed unlikely he could start a successful rebellion. Feeling lost, he traveled east to Östergötland in Sweden just before Christmas. There, he met Birger Brosa, a local ruler married to Sigurd Munn's sister. Sverre told Birger Brosa about his claim to the throne. At first, Birger didn't want to help. He was already supporting another group, the Birkebeiners, also known as the Birchlegs. This group had started in 1174, led by Øystein Møyla, who claimed to be King Øystein Haraldsson's son. They were called Birkebeiners because they were so poor that some of them wrapped birch bark around their legs instead of wearing shoes.

But in January 1177, the Birkebeiners lost badly at the Battle of Re, and Øystein died. Sverre met the remaining Birkebeiners in Värmland. After some hesitation, Sverre was convinced to become their new leader.

Sverre's Rise to Power

When Sverre first met them, the Birkebeiners were a small, disorganized group of only about 70 men, according to the saga. Many people see Sverre's ability to turn them into skilled soldiers as proof of his great leadership.

Tough Early Years

In his first years as the Birkebeiner leader, Sverre and his men were almost always moving. Most people saw the Birkebeiners as troublemakers who had little chance of winning. People mostly wanted peace. Even though peasant groups were no match for the experienced Birkebeiners, King Magnus or Erling Skakke often kept the Birkebeiners on the run.

In June 1177, Sverre first led his men to Trøndelag. There, Sverre was declared king at Øretinget. This was the traditional place to choose a king, so it was a very important event. The Birkebeiners then moved south to Hadeland, but they were forced north again. Sverre then decided to go west, hoping to surprise and capture Bergen. However, at Voss, local peasants ambushed the Birkebeiners. The Birkebeiners won, but the surprise attack on Bergen was no longer possible. This forced them to go east again. After almost freezing to death on Sognefjell, they spent the winter in Østerdal.

The next spring, after a short stay in Viken, Sverre and the Birkebeiners went back to Trøndelag. The Birkebeiners now decided to fight more directly. But an attack on Nidaros ended in defeat at the Battle of Hatthammeren. After running south, they met Magnus's army in Ringerike. This fight ended with a small win for the Birkebeiners. Encouraged, they returned to Trøndelag and managed to control the area enough to stay in Nidaros for the winter.

In the spring of 1179, Magnus and Erling Skakke attacked Nidaros, forcing Sverre to seem to retreat again. Magnus and his men thought the Birkebeiners had fled south. But Sverre had turned around at Gauldal and marched back towards the city. The two armies met on June 19 in the Battle of Kalvskinnet. Erling Skakke was killed in this battle, which was a clear victory for Sverre. This win made Sverre's control over Trøndelag secure.

Winning Against the Heklungs

After Sverre's victory at Kalvskinnet, the war changed. The people of Trøndelag accepted Sverre as their king. The two sides were now much more equal in strength. At some point, Magnus's group got the nickname Heklungs. This name probably referred to the traditional clothes worn by monks.

Several battles followed. Magnus Erlingsson attacked Trøndelag again in the spring of 1180. This time, he had more soldiers from western Norway. But in the Battle of Ilevollene, just outside Nidaros, the Heklungs were defeated again, and Magnus fled to Denmark. With Magnus out of the country, Sverre could sail south and take Bergen. However, his control over that region was still weak.

Magnus was determined to win a big victory against the Birkebeiners. He returned with his fleet the next year. The two forces met at sea on May 31, 1181, in the Battle of Nordnes. The Birkebeiners won a small victory; the Heklungs ran away when they mistakenly thought Magnus had been killed. Since his men were in bad shape, Sverre decided to go back to Trøndelag. Some talks were held to make peace, but they quickly failed. Magnus would not accept Sverre as an equal king, and Sverre would not become Magnus's servant.

Magnus controlled western Norway from Bergen. This made it hard for Sverre to get supplies for his men. So, Sverre led his men south to Viken, which was a strong Heklung area. He let his men take supplies there, which didn't hurt his cause much. However, Magnus used Sverre's absence well. In November, he attacked Trøndelag and managed to capture and burn the Birkebeiner fleet. Sverre had to return or risk losing his only safe base.

In the summer of 1182, Magnus tried to capture Nidaros by surrounding it. But he was pushed back with heavy losses when the Birkebeiners launched a surprise night attack. Sverre then started building many new ships. Without a fleet, he couldn't hope to expand his power further south. In the spring of 1183, Sverre attacked Bergen with some of his new fleet. He avoided being seen by enemy scouts and caught the Heklungs by surprise, taking their entire fleet. Magnus fled to Denmark, leaving his crown and sceptre behind.

In sea battles during the Middle Ages in Scandinavia, the side with the largest and tallest ships usually had an advantage. This meant the crew could attack the enemy from above with arrows and other weapons. Sverre built the biggest ship at the time, the Mariasuda. Because it was so big, the Mariasuda was not very good in rough seas. It was only useful inside the narrow fjords. By luck or good planning, a situation where it would be useful soon came up.

In early spring 1184, Magnus returned to Viken from Denmark with new ships. In April, he sailed north towards Bergen. Around the same time, Sverre had gone to Sogn to stop a local uprising and was still there when Magnus arrived in Bergen in June. After chasing away the few Birkebeiners there, Magnus sailed again, having heard where Sverre was. The two fleets met on June 15 at Fimreite in the long and narrow Sognefjord. The Battle of Fimreite was the final fight between the Birkebeiners and the Heklungs. Magnus had several large ships, but none as huge as the Mariasuda. While the Mariasuda held back half of the enemy fleet, the rest of Sverre's ships attacked the other enemy ships. Panic spread as the Heklungs tried to escape onto their larger ships. These ships quickly became too heavy and began to sink. Many wounded and tired men couldn't stay afloat and drowned, including King Magnus. Most of the Heklung leaders died there, along with many men on both sides. Without a leader, the Heklungs were no longer a political group. Sverre could now, after six years of fighting, finally claim to be the only and undisputed king of Norway.

Sverre's Challenging Reign

Now that the determined priest and his group of wanderers had become king and rulers of Norway, Sverre worked to make his power strong. He put his loyal men in important positions (sysselmann) across the kingdom. He also arranged marriages between the old noble families and the new ones. Sverre himself married the Swedish princess Margaret. She was the daughter of Erik the Saint and sister of King Knut Eriksson of Sweden.

Norway had seen many conflicts before, but usually, the winner would make peace with his opponents. However, in Sverre's case, making peace was hard. This war had been long and had caused more deaths than earlier conflicts. Most of the old noble families had lost members and wanted revenge. Also, many people found it hard to accept that common people were now given noble titles. Peace did not last long.

Kuvlungs and Øyskjeggene

In the autumn of 1185, the Kuvlungs started a rebellion in Viken. Their leader, Jon Kuvlung, was a former monk. He claimed to be the son of Inge the Hunchback. This group was like a direct continuation of the Heklungs, with many members coming from former Heklung families. The Kuvlungs quickly took control of eastern and western Norway, which were the old Heklung strongholds.

In the autumn of 1186, the Kuvlungs attacked Nidaros. This attack surprised Sverre. He took shelter in the newly built stone castle Sion. The Kuvlungs couldn't take the castle and had to retreat. In 1188, Sverre sailed south with a large fleet. They first met at Tønsberg, but neither side dared to fight. The Kuvlungs secretly went to Bergen. Sverre attacked Bergen just before Christmas. Jon Kuvlung was killed, which ended the Kuvlung rebellion. Some smaller uprisings followed, but these were just small groups of bandits and were stopped locally.

The next serious threat came in 1193 with the Øyskjeggene (the Isle Beards). This group's claim to the throne was Sigurd, a child said to be the son of Magnus Erlingsson. The real leader was Hallkjell Jonsson, who was Magnus’s brother-in-law. Hallkjell worked with the earl of Orkney, Harald Maddadsson. He gathered most of his men on the Orkney and Shetland Islands, which is where the group got its name. After settling in Viken, the Øyskjeggene sailed to Bergen. They took control of the city and the areas around it, but a group of Birkebeiners held out in Sverresborg castle. In the spring of 1194, Sverre sailed south to fight the Øyskjeggene. The two fleets met on April 3 in the Battle of Florvåg. Here, the battle experience of the Birkebeiner veterans was key to their victory. Hallkjell died along with most of his men.

Sverre and the Church

The Church in Norway had been organized under the Archbishopric of Nidaros in 1152. Øystein Erlendsson, who became archbishop in 1161, was one of Magnus Erlingsson's main supporters. In return, the Church had secured its position as an independent organization and gained many other special rights.

Øystein returned to Nidaros from England in 1183. During his last years, there was a truce between the Church and the king. When Øystein died on January 26, 1188, Eirik Ivarsson, the bishop of Stavanger, was chosen as his replacement. Sverre probably hoped that his relationship with the Church could become normal. He approached Eirik, hoping to be crowned, which would be a clear sign of recognition. However, Eirik saw Sverre as someone who had illegally taken the throne and killed the king.

The situation quickly turned into an open conflict. Sverre began to create new rules that went against the Church's laws, which were based on the rules made by St. Olaf, the traditional founder of the Norwegian Church. Eirik, on his side, spoke out against the king and his men. He also sent letters of complaint to the Pope. But at first, he had few ways to fight back. In 1190, Sverre tried to force the archbishop to obey him. He claimed that Eirik had broken the law by having 90 armed men serving him. By law, the archbishop's guard was limited to 30 men. Instead of obeying the king, Eirik fled to Lund, where the Danish archbishop lived. From there, he sent a group to Rome to ask the pope for advice.

With the archbishop gone, Sverre put more pressure on the bishops, especially Nikolas Arnesson. Nikolas was the half-brother of Inge Krokrygg. He had become bishop of Oslo in 1190, even though Sverre didn't want him to. After the Øyskjeggs were defeated at Florvåg, Sverre met with Nikolas. Sverre claimed to have proof that the bishop had worked with the Øyskjeggs. The king accused Nikolas of betrayal and threatened him with severe punishment. Nikolas gave in. On June 29, he and the other bishops crowned Sverre. Sverre's own priest was chosen as bishop of Bergen.

Meanwhile, Archbishop Eirik finally received a reply from Rome. In a letter dated June 15, 1194, Pope Celestine III explained the basic rights of the Norwegian Church, supporting Eirik on every point. With this letter, Eirik could take the step of excommunicating Sverre. He also ordered the Norwegian bishops to join him in exile in Denmark.

The next spring, Sverre sent Bishop Tore of Hamar, who was still loyal, to Rome to argue his case to the pope. According to the saga, Tore returned in early 1197 with a papal letter that canceled Sverre's excommunication. In Denmark, Tore is said to have become sick and died under strange circumstances. But not before he had used the papal letter as a guarantee for a loan. The people who lent him money then traveled to Norway and gave the letter to Sverre, who used it to his advantage. No other sources confirm this story, and most historians now believe the letter was fake.

When Pope Celestine died in January 1198, the conflict paused briefly until the new pope, Innocent III, caught up on the situation. Then the conflict grew even bigger. In October, Innocent III placed Norway under interdict, which meant many church services were forbidden. In letters to Eirik, he accused Sverre of faking the letter. He also sent letters telling neighboring kings to remove Sverre from power. But they did the opposite: Sweden continued to actively support the Birkebeiners, and John of England sent soldiers to help Sverre. In 1200, Innocent felt it was necessary to warn the Archbishop of Canterbury not to accept any more gifts from Sverre.

Around this time, someone close to Sverre wrote a speech against the bishops. In this work, the unknown author discussed the relationship between the King and the Church. The author tried to prove that Sverre's excommunication was unfair and therefore not valid. The author also tried to defend Sverre's right to appoint bishops. To support this, he had to explain Norwegian law, even though the Church had long seen this as buying church positions. By now, Sverre was very busy with the Bagler rebellion, which was supported by the Church. So, the direct fight with the Church became less important for him personally.

The Bagler War

In the spring of 1196, the Bagler party was formed in Halør, Denmark, to oppose Sverre. Their leaders were Nikolas Arnesson, the nobleman Reidar Sendemann from Viken, and Sigurd Jarlsson, a son of Erling Skakke. Archbishop Eirik also supported them. They chose Inge Magnusson, supposedly the son of Magnus Erlingsson, as their king. Then they sailed back to Norway.

Sverre happened to be in Viken, and the two forces soon met, though no major battles were fought. Sverre gave his oldest son, Sigurd Lavard, the job of guarding a large crossbow (a ballista) he had built. However, the Baglers launched a surprise night attack. The ballista was destroyed, and Sigurd and his men were chased away. Sverre was very angry and never gave his son a command again. After some more fighting that didn't decide anything, Sverre sailed north to Trondheim, where he spent the winter. The Baglers had Inge declared king at Borgarting and soon took strong control over the Viken region, with Oslo as their main base.

In the spring of 1197, Sverre called up the leidang (a type of army draft) from the northern and western parts of the country. In May, he was able to sail south to Viken with more than 7,000 men, a very large force. The Birkebeiners attacked Oslo on July 26. After many deaths on both sides, the Baglers were forced to retreat inland. Sverre then spent some time collecting war taxes from the region. But his leidang troops were close to rebelling, so Sverre went back to Bergen, where he decided to spend the winter. This turned out to be a nearly fatal mistake. The Baglers had traveled north to Trøndelag by land and entered Nidaros with little resistance. The soldiers at Sverresborg castle held out for a while until their commander, Torstein Kugad, switched sides and let the Baglers into the castle. The Baglers completely took apart Sverresborg. Sverre's home region was now in enemy hands.

The year 1198 was the lowest point for Sverre. In May, Sverre tried to take back Trøndelag. This time, Sverre failed to surprise the enemy, and the Birkebeiner fleet was mostly made up of smaller ships. In the sea battle that followed, the Birkebeiners were soundly defeated. After this battle, the Baglers took even stronger control of Trøndelag, and many people joined what they thought was the winning side.

After his defeat, Sverre went back to Bergen. He was soon followed by a larger Bagler army led by Nikolas Arnesson and Hallvard of Såstad. Sverre continued to hold Bergenhus fortress. This castle proved to be impossible to capture, giving the Birkebeiners a safe base. The following summer was called the "Bergen’s summer." It was mostly filled with small, undecided fights in the Bergen area. On August 11, the Baglers set fire to Bergen. The destruction was complete; even the churches were burned down. Facing starvation, Sverre secretly left with most of his men to Trøndelag.

In Trøndelag, most of the people were still loyal to Sverre. Many of those who had joined the Baglers now switched sides again. Sverre was also able to use the Baglers' harsh actions in Bergen against them. The people of Trøndelag promised to give Sverre a new fleet. In total, 8 large ships were built, and several transport ships were changed into warships. The Baglers sailed into the Trondheimsfjord in early June. On June 18, 1199, the two fleets met at the Battle of Strindafjord. Sverre won a huge victory here, and the remaining Baglers fled to Denmark.

Sverre could now take control over Viken and planned to spend the winter in Oslo. But the countryside remained largely against him. Early the next year, a sudden uprising happened as many people started gathering near Oslo to drive out the Birkebeiners. This peasant army was untrained and disorganized. It was no match for the experienced Birkebeiners. In a battle on March 6, 1200, the peasants were defeated piece by piece. However, the Birkebeiners' control over the region was still weak, and Sverre decided to sail back to Bergen.

With Sverre gone, the Baglers could return strongly from Denmark. Soon, they had re-established their control over Eastern Norway. The two sides then spent a year attacking each other's lands, with no lasting gains for either side, although the Birkebeiners were stronger at sea.

In the spring of 1201, Sverre sailed out from Bergen with a large leidang force. This would be his last military campaign. With this army, he could demand war taxes without opposition on both sides of the Oslofjord during the summer. In September, he set up camp at Tønsberg and began to surround Tønsberg Fortress. Reidar Sendemann and his men were defending the fortress. The siege lasted a long time because the other Bagler leaders didn't dare to send help, and the defenders didn't fall for any of Sverre's tricks. Finally, on January 25, Reidar and his men gave up. Sverre decided to sail back to Bergen.

During the journey back, Sverre became ill. By the time they reached Bergen, the king was dying. On his deathbed, Sverre named his only living son, Håkon, as his heir and successor. In a letter, he told Håkon to try to make peace with the Church. Sverre died on March 9, 1202. He was buried in Christ Church, Bergen, which was destroyed in 1591.

|

See also

In Spanish: Sverre I de Noruega para niños

In Spanish: Sverre I de Noruega para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |