Ballista facts for kids

The ballista was an ancient missile weapon. It was like a giant crossbow. It could launch either large bolts (like huge arrows) or heavy stones. These weapons were used to hit targets far away.

The ballista was developed from older Greek weapons. It worked differently from a regular bow. Instead of a simple bowstring, it used two levers with special springs. These springs were made of many loops of twisted rope. Early ballistas shot heavy darts or round stones. They were used in siege warfare to attack enemy cities. Later, smaller, more accurate versions were made, like the scorpio.

Contents

Greek Weapon

The first ballistas in Ancient Greece came from two earlier weapons. These were called the oxybeles and the gastraphetes. The gastraphetes was a handheld crossbow. It was powered by a strong bow. To load it, a soldier would push the weapon against their stomach. This allowed a person of average strength to use it. It was powerful enough to hurt armored soldiers.

The oxybeles was much bigger and heavier. It used a winch to pull back the string. It was placed on a tripod and fired slower. It was used as a siege engine to break down walls.

A big step forward was the invention of the torsion spring. This spring was made of tightly twisted ropes. This new technology allowed ballistas to shoot lighter objects much faster. They could also shoot them over longer distances. Regular bows were slower. They could not transfer as much power to light objects. This limited their range.

The very first ballista is thought to have been made around 400 BC. It was built for Dionysius of Syracuse.

The Greek ballista was mainly a siege weapon. Its parts were carried by the army. If needed, the wooden parts could be made from local trees. Some ballistas were placed inside large, armored siege towers. Others were used on the edge of a battlefield.

Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander made the ballista famous. They used it as both a siege engine and battlefield artillery. Philip II had engineers in his army to design these weapons. Some say he even invented the ballista by improving Dionysius's device. Alexander's engineers made it even better. They used springs made of tightly twisted rope coils. This gave the weapons more energy and power.

Polybius wrote about smaller, portable ballistas. These were called scorpions. They were used during the Second Punic War.

Ballistas could be changed easily. They could shoot both round stones and long darts. This helped soldiers adapt quickly during battles.

Later, a special joint was added to the ballista's stand. This was called a universal joint. It allowed operators to change where the ballista aimed. They could also change how far it shot. This meant they didn't have to take the machine apart to adjust it.

Roman Weaponry

When the Roman Republic took over the Greek city-states in 146 BC, Roman soldiers learned about Greek technology. This included the amazing military machines the Greeks had built. The Romans adopted the torsion-powered ballista. This weapon had spread to many cities around the Mediterranean Sea. Many of these cities became Roman property after wars.

The Romans improved Alexander's torsion ballista even more. They made much smaller versions. These could be carried easily by soldiers.

Early Roman Ballistae

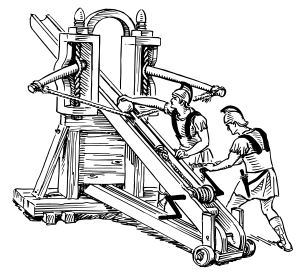

Early Roman ballistas were made of wood. Iron plates and nails held the wooden parts together. The main part had a sliding groove on top. This is where the bolts or stones were loaded. At the back, there were two winches and a claw. These were used to pull the bowstring back into the firing position.

The sliding part went through the weapon's frame. Inside the frame were the torsion springs. These were ropes made of animal sinew. They were twisted around the bow arms. The bow arms were connected to the bowstring.

Pulling the bowstring back with the winches twisted the already tight springs. This stored energy to fire the projectiles. Bronze or iron caps held the twisted rope bundles. These caps could be adjusted with pins. This allowed the weapon to be tuned for power. It also helped with changing weather conditions.

The ballista was a very accurate weapon. There are many stories of Roman archers (called ballistarii) picking off single enemy soldiers. Its maximum range was over 500 yards (457 meters). But its effective combat range was much shorter for most targets.

The Romans kept improving the ballista. It became a very important weapon in the army of the Roman Empire.

Julius Caesar used it during his conquest of Gaul. He also used it in both of his campaigns to conquer Britain.

First Invasion of Britain

Caesar's first invasion of Britain happened in 55 BC. He had quickly conquered Gaul. He wanted to stop the Britons from sending help to fight the Romans in Gaul.

Eighty ships carrying two legions tried to land on the British shore. But many British warriors were waiting there. The ships had to unload their troops on the beach. It was the only suitable beach for miles. But the British chariots and javelin throwers made it very hard.

Caesar ordered his warships to move closer to the shore. These ships were faster and easier to handle. They also looked strange to the natives. From the ships, soldiers used slings, bows, and ballistas to push the Britons back. This plan worked very well. The Britons were scared by the warships' strange shape. They were also afraid of the moving oars and the unfamiliar machines. They stopped and retreated. (Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul, p.99)

Siege of Alesia

In Gaul, the city of Alesia was under a Roman siege in 52 BC. The Romans completely surrounded it with fortifications. These included a wooden palisade and towers. Small ballistas were placed in these towers. Other soldiers with bows or slings were also there. The Romans also used ballistas in the Siege of Masada.

Ballistas in the Roman Empire

During the Roman Empire's conquests, the ballista proved very useful. It helped in many sieges and battles, both on land and at sea. Many ballista parts found by archaeologists today are from this time. Old technical manuals and journals help archaeologists rebuild these weapons.

After Julius Caesar, the ballista was always part of the Roman army. Engineers kept making changes and improvements. They replaced more wooden parts with metal. This made the machines smaller, lighter, and more powerful. They also needed less care. However, the important torsion springs could still wear out.

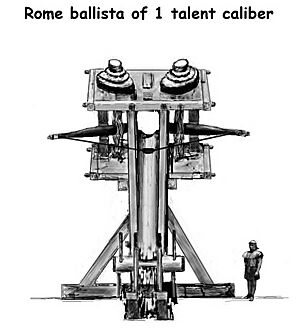

The largest ballistas in the 4th century could throw a dart over 1,200 yards (1,100 meters). One weapon was called ballista fulminalis. It could shoot many large darts over long distances, like across the Danube River. Ballistas were not just for attacking. After 350 AD, at least 22 round towers were built around the walls of Londinium (London). These towers held defensive ballistas.

Eastern Roman Empire

In the 6th century, a writer named Procopius described how the ballista worked. He said it looked like a bow. It had a grooved wooden shaft that moved. When soldiers wanted to shoot, they bent the bow parts with a rope. They put an arrow in the groove. This arrow was half the length of a normal arrow but four times wider.

Procopius wrote that the missile shot out with great force. It could travel at least two bow-shots away. When it hit a tree or rock, it easily pierced it. He said the weapon was called a ballista because it shot with very great force. The missiles could even go through body armor.

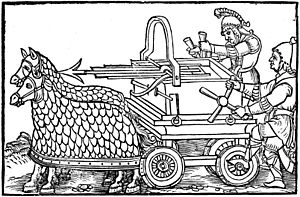

Carroballista

The carroballista was a ballista mounted on a cart. There were probably different types of these cart-mounted ballistas. Some had two wheels, and some had four. They were about 1.47 meters (5 Roman feet) wide. Being on a cart made them very flexible in battle. They could be moved easily as the fight changed. This weapon is shown many times on Trajan's Column.

Polybolos

Some people think the Roman army might have had a "repeating" ballista. This was also known as a polybolos. A BBC documentary rebuilt one of these weapons. They found it could shoot eleven bolts a minute. This is almost four times faster than a regular ballista. However, archaeologists have not found any real examples of such a weapon.

Cheiroballistra and Manuballista

Many archaeologists believe the cheiroballistra and the manuballista were the same weapon. The different names might come from the different languages spoken in the Empire. Latin was the official language in the Western Roman Empire. But the Eastern Empire mostly used Greek. Greek added an extra 'r' to the word ballista.

The manuballista was a handheld version of the traditional ballista. This new version was made entirely of iron. This made the weapon more powerful because it was smaller. Less iron was used, which was good because iron was expensive before the 1800s. It was not the ancient gastraphetes, but a Roman weapon. However, it had similar physical limits to the gastraphetes.

Archaeology and the Roman Ballista

Archaeology, especially experimental archaeology, has taught us a lot about ballistas. Some ancient writers, like Vegetius, wrote very detailed technical books. These books gave all the information needed to rebuild the weapons. But all their measurements were in their own language, which made them hard to translate.

People started trying to rebuild these ancient weapons in the late 1800s. They used rough translations of old writings. But it was only in the 1900s that many of the reconstructions started to make sense as weapons. Modern engineers helped understand the ancient measurement systems. With this new information, archaeologists could recognize parts found at Roman military sites. They could then identify them as ballista parts. Information from these digs helped improve the next generation of reconstructions.

Sites across the Roman Empire have given us information about ballistas. These include Spain (the Ampurias Catapult) and Italy (the Cremona Battleshield). The Cremona find showed that the weapons had decorative metal plates to protect the operators. Other sites are in Iraq (the Hatra Machine) and even Scotland (Burnswark siege tactics training camp).

The most important archaeologists in this area are Peter Connolly and Eric Marsden. They have written a lot about ballistas. They have also made many reconstructions themselves. They have improved the designs over many years.

Middle Ages

As the Roman Empire declined, it became harder to build and keep up these complex machines. So, the ballista was likely replaced by simpler and cheaper weapons. These included the onager and the more efficient springald.

The ballista became less popular as new siege engines spread. Weapons like the trebuchet and the mangonel were more efficient. But the ballista was still used sometimes in Medieval Siege Warfare. City and castle defenders especially used them. It finally became rare when medieval cannons became common in European cities by the early 1300s.

Records from Littere Wallie show that four ballistas were at Dolwyddelan Castle in 1280. One was at Rhuddlan Castle and one large ballista at Castell y Bere in 1286. All these were held by the English Crown.

In places like Ireland, cannons were rare. Personal firearms were almost non-existent. So, ballistas were still used there even in the late 1400s.

The word "ballista" also lives on in the name of the arbalest crossbow. The word "arbalest" comes from arcus (meaning 'bow') and ballista.

See also

In Spanish: Balista para niños

In Spanish: Balista para niños

- Harpax

- Roman infantry tactics

- Roman military personal equipment

- Roman siege engines