Henrik Wergeland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henrik Wergeland

|

|

|---|---|

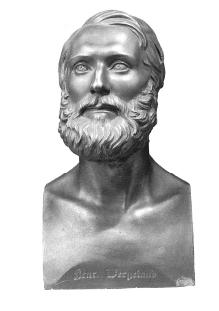

Henrik Wergeland

|

|

| Born | Henrik Arnold Thaulow Wergeland 17 June 1808 Kristiansand, Denmark-Norway |

| Died | 12 July 1845 (aged 37) Christiania (now Oslo), Norway |

| Pen name | Siful Sifadda (farces) |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright and non-fiction writer |

| Period | 1829–1845 |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

Henrik Arnold Thaulow Wergeland (born June 17, 1808 – died July 12, 1845) was a famous Norwegian writer. He is best known for his amazing poems. He was also a playwright, a debater, a historian, and a language expert. Many people see him as a key person who helped create a special Norwegian literature and modern Norwegian culture.

Even though Wergeland only lived to be 37, he explored many different areas. These included literature, religion, history, politics, social issues, and science. His ideas were often debated during his time. Some people even called his writing style rebellious.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Henrik Wergeland was the oldest son of Nicolai Wergeland. His father was part of the group that wrote Norway's constitution in 1814. Henrik grew up in Eidsvoll, a very important place for Norwegian patriotism. His younger sister was Camilla Collett, who also became a famous writer. His younger brother was Major General Joseph Frantz Oscar Wergeland.

In 1825, Henrik started studying at The Royal Frederick University. He planned to become a priest and finished his studies in 1829.

Fighting for Norway's National Day

In 1829, Wergeland became a symbol for celebrating Norway's constitution on May 17th. This day later became Norway's National Day. He became a public hero after an event called the "battle of the Square" in Christiania. This happened because the king had forbidden any celebration of the national day.

Wergeland was there and became known for standing up against the local leaders. He was later the first person to give a public speech for the day. Because of this, he is often given credit for starting the tradition. Every year, students and schoolchildren decorate his grave and statues on May 17th. The Jewish community in Oslo also honors him on this day. They do this to thank him for his successful efforts to allow Jewish people into Norway.

Early Poetry and Ideas

In 1829, Wergeland published a book of poems called Digte, første Ring (Poems, First Circle). This book made him very well-known. In it, he wrote about his ideal love, a character named Stella. Stella was inspired by four real girls Wergeland had feelings for.

The character of Stella also inspired his long epic poem, Skabelsen, Mennesket og Messias (Creation, Man and the Messiah). He later rewrote it in 1845 as Mennesket (Man). In these works, Wergeland explored the story of humans and God's plan for them. His writings showed ideas from the Age of Enlightenment and the French revolution. He often criticized people who misused their power.

Wergeland believed in freedom and truth for everyone. He wrote:

- Heaven shall no more be split

- after the quadrants of altars,

- the earth no more be sundered and plundered

- by tyrant's sceptres.

- Through the gloom of priests, through the thunder of kings,

- the dawn of freedom,

- bright day of truth

- shines over the sky, now the roof of a temple,

- and descends on earth,

- who now turns into an altar

- for brotherly love.

By the age of 21, he was a powerful voice in literature. His strong support for the ideas of the French July revolution of 1830 also made him important in politics. He worked hard to help Norway as a nation. He started public libraries and tried to help poor farmers. He encouraged a simple life and wore Norwegian clothes. He wanted people to be educated and understand their rights. This made him very popular among ordinary people.

In his essay Hvi skrider Menneskeheden saa langsomt frem? (Why does humanity progress so slowly?), Wergeland shared his belief that God would guide humanity toward progress and better times.

Challenges and Debates

Some critics, especially Johan Sebastian Welhaven, said Wergeland's early writing was wild and lacked structure. They felt he had a lot of imagination but not enough taste or knowledge. From 1830 to 1835, Welhaven and others strongly criticized Wergeland. Welhaven preferred a more traditional style and did not like Wergeland's energetic writing.

Welhaven even wrote an essay criticizing Wergeland's style. In response, Wergeland published several funny poems using the pen name "Siful Sifadda." The disagreement started as a small argument among students. But it grew into a long public debate in newspapers for almost two years. Welhaven's criticism and the negative talk from his friends created a lasting bias against Wergeland's early works.

Modern View of His Poetry

Recently, Wergeland's early poems have been looked at again and are now more appreciated. His poetry can be seen as surprisingly modernistic. It also has parts that remind us of old Norwegian Eddic poems. Like ancient Norse poets, his writing is vivid and sometimes uses complex kennings (poetic descriptions).

From early on, he wrote poems in a free style, without rhymes or a strict rhythm. He used strong and complex metaphors. Many of his poems were quite long. He wanted readers to think deeply about his poems, just like poets such as Byron, Shelley, or even Shakespeare did. This free form and the many ways his poems could be understood especially bothered Welhaven. Welhaven believed poetry should focus on one topic at a time.

Wergeland had been writing in Danish, but he supported the idea of Norway having its own independent language. He thought about this 15 years before Ivar Aasen started working on a new Norwegian language. Later, the historian Halvdan Koht said that "there is not one political cause in Norway which has not been seen and anticipated by Henrik Wergeland."

Wergeland's Personality

Wergeland had a strong personality and was always ready to fight for fairness. At that time, many people in rural areas were poor, and a system called serfdom was common. He often did not trust lawyers because of how they treated farmers, especially poor ones. He frequently argued against lawyers in court, who could legally take over small farms. This made him many enemies. One legal problem lasted for years and almost made him lose all his money.

Wergeland was tall for his time, about 1 meter and 80 centimeters (about 5 feet 11 inches). He often looked up, especially when riding his horse through town. His horse, Veslebrunen (little brown), was a small Norwegian breed. So, when Wergeland rode, his feet sometimes dragged on the ground!

A Playwright's Competition

In the autumn of 1837, Wergeland entered a playwriting competition for the theater in Christiania. He came in second place, just behind Andreas Munch. Wergeland had written a musical play called Campbellerne (The Campbells). This play used songs and poems by Robert Burns. The story talked about British rule in India and serfdom in Scotland. It also criticized social problems in Norway, like poverty and greedy lawyers. The play was an instant hit with the audience. Many later thought it was his biggest success in theater.

The "Battle of the Campbells"

However, trouble started on the second night of the play, January 28, 1838. Twenty-six important gentlemen from the university, court, and government came to the performance. They wanted to stop Wergeland once and for all. They bought the best seats and brought small toy-trumpets and pipes. They started interrupting the play from the very beginning. The noise grew, and the police chief could only shout for order.

It was said that these important gentlemen acted like schoolboys. One of them even shouted loudly in Nicolai Wergeland's ear. The poet's father was shocked. This attacker was supposedly Frederik Stang, who later became Norway's prime minister. An actor finally calmed the audience, and the play continued. After the play, ladies in the front rows threw rotten tomatoes at the troublemakers. Fights then broke out inside and outside the theater. Some of the gentlemen tried to escape but were pulled back for more fighting. The troublemakers were ashamed for weeks and did not show themselves for a while. A member of the Norwegian Parliament saw and wrote down the story of this event, called "the battle of the Campbells."

Wergeland's supporters seemed to win that day. But the powerful men might have gotten revenge by spreading bad rumors about Wergeland after he died. In February, a special performance was held to benefit Wergeland. This gave him enough money to buy a small house outside town, in Grønlia.

Marriage and Family Life

From his new home in Grønlia, Wergeland often rowed across the fjord to an inn in Christiania. There, he met Amalie Sofie Bekkevold, who was 19 years old and the inn owner's daughter. Wergeland quickly fell in love and proposed that same autumn. They got married on April 27, 1839, in the church of Eidsvoll. Wergeland's father was the priest who married them.

Amalie came from a working-class family, but she was charming, funny, and smart. She quickly won over her husband's family. Camilla Collett, Wergeland's sister, became her close friend for life. Henrik and Amalie did not have children together. However, they adopted Olaf, a son Wergeland had in 1835. Wergeland made sure Olaf received an education. Olaf Knutsen, as he was called, later became important in Norwegian school-gardening and was a well-known teacher.

Amalie inspired Wergeland to write a new book of love poems. This book was full of images of flowers, while his earlier love poems had used images of stars. After Wergeland's death, Amalie married Nils Andreas Biørn, a priest who was an old college friend of Wergeland's. She had eight children with him. But when she died many years later, her eulogy (a speech praising her) said: "The widow of Wergeland has died at last, and she has inspired poems like no-one else in Norwegian literature."

Work and Career

For many years, Wergeland tried to get a job as a chaplain or priest. He was always turned down. This was mostly because employers thought his way of living was "irresponsible" and "unpredictable." His legal problems with Praëm also made it difficult. The department said he could not get a church job while that case was still ongoing.

Meanwhile, Wergeland worked as a librarian at the University Library starting in January 1836. He also edited a magazine called Statsborgeren from 1835 to 1837. In late autumn 1838, King Carl Johan offered him a small "royal pension." This nearly doubled his salary. Wergeland accepted it as payment for his work as a "public teacher." This pension gave him enough money to get married and settle down.

His marriage made him calmer. He applied again, this time for the new job as head of the national archive. He applied in January 1840 and eventually got the job. He worked there from January 4, 1841, until he had to retire in the autumn of 1844. On April 17, 1841, he and Amalie moved to his new home, Grotten. It was located near the new Norwegian royal palace. He lived there for the next few years.

Later Challenges

After he got his job, some of Wergeland's old friends in the republican movement suspected him of betraying their cause. They felt that as a left-wing supporter, he should not have accepted anything from the King. Wergeland had mixed feelings about Carl Johan. On one hand, the King represented ideas from the French Revolution, which Wergeland admired. On the other hand, he was the Swedish king who had prevented Norway's full independence. The radicals called Wergeland a traitor, and he defended himself in many ways. But it was clear he felt lonely and betrayed.

He was not allowed to write in some of the bigger newspapers. So, he could not defend himself. The newspaper Morgenbladet would not print his replies, not even his poems. One of his most famous poems was written at this time. It was a response to the paper saying Wergeland was "irritable and in a bad mood." Wergeland wrote:

I in a bad mood, Morgenblad? I, who need nothing more than a glimpse of sun to burst out in loud laughter, from a joy I cannot explain?

The poem was printed in another newspaper. Morgenbladet later printed the poem with an apology to Wergeland in the spring of 1846.

In January 1844, the court decided on a compromise in the Praëm case. Wergeland had to pay 800 speciedaler, which was more than he could afford. He felt humiliated. He had to sell his house, Grotten. A good friend of his bought it the following winter, understanding Wergeland's difficult situation. The stress from these problems may have contributed to his illness.

Final Illness and Death

In the spring of 1844, Wergeland got pneumonia and had to stay home for two weeks. While recovering, he insisted on joining the national celebrations that year. His sister Camilla saw him, "pale as death, but in the spirit of 17 May," on his way to the festivities. Soon after, his illness returned, and he also showed signs of tuberculosis. He had to stay inside, and his illness turned out to be fatal. There have been many ideas about what caused his sickness. Some believe he developed lung cancer after a lifetime of smoking. At that time, most people did not know the dangers of smoking.

During this last year, he wrote very quickly from his sickbed. He wrote letters, poems, political statements, and plays.

Because of his money problems, Wergeland moved to a smaller house, Hjerterum, in April 1845. Grotten was then sold. But his new home was not ready, so he had to spend ten days at the national hospital Rikshospitalet. There, he wrote some of his most famous sickbed poems. He wrote almost until the very end. His last known poem is dated July 9, just three days before he died.

Henrik Wergeland passed away at his home early on July 12, 1845. His funeral was held on July 17. Thousands of people attended, many traveling from areas around Christiania. The priest expected a few hundred, but the crowd was ten times larger. Norwegian students carried his coffin, while the planned wagon went empty in front of them. It is said that the students insisted on carrying the coffin themselves. Wergeland's grave was left open that afternoon. All day, people honored him by placing flowers on his coffin until evening. His father wrote his thanks in Morgenbladet three days later, saying his son had finally received the honor he deserved.

Grave Site Change

Wergeland was first buried in a simple part of the churchyard. Soon, his friends started writing in newspapers, asking for a better burial site for him. He was eventually moved to his current grave in 1848. At this time, people debated what kind of monument his grave should have. The monument on his grave was paid for by Swedish Jews. It was officially unveiled on June 17, 1849, after a six-month delay.

Legacy and Influence

Wergeland's statue stands between the Royal Palace and the Storting (Norway's parliament) on Oslo's main street. On Norwegian Constitution Day, students from the University of Oslo place a wreath of flowers on it every year. This monument was put up on May 17, 1881. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, another famous Norwegian writer, gave a speech at the event.

During the Second World War, the Nazi occupiers banned any celebration of Wergeland.

Wergeland became a symbol for the Norwegian Left-wing movement. Many later Norwegian poets, even today, have been inspired by him. The Norwegian poet Ingeborg Refling Hagen said, "When in our footprints something sprouts,/ it's a new growth of Wergeland's thoughts." She helped start an annual celebration on his birthday. She began the traditional "flower-parade" and celebrated his memory with readings and songs, often performing his plays.

Wergeland's most important poetic symbols are the flower and the star. They represent heavenly and earthly love, nature, and beauty. His poems have been translated into English by several people, including Illit Gröndal and Anne Born.

Works

The complete writings of Henrik Wergeland (Samlede Skrifter : trykt og utrykt) were published in 23 volumes between 1918 and 1940. An earlier collection, also called Samlede Skrifter (9 volumes, Christiania, 1852–1857), was edited by H. Lassen.

Wergeland's narrative poems are very important in Norwegian literature. These include Jan van Huysums Blomsterstykke (Flower-piece by Jan van Huysum, 1840), Svalen (The Swallow, 1841), Jøden (The Jew 1842), Jødinden (The Jewess 1844), and Den Engelske Lods (The English Pilot 1844). He was less successful with his plays. His historical work, Norges Constitutions Historie (The History of the Norwegian Constitution) 1841–1843, is still seen as an important source. Many of the poems from his later years are beautiful and are considered lasting treasures of Norwegian poetry.

Family Background

Wergeland's father was the son of a bellringer. His family on his father's side were mostly farmers from different parts of Norway. On his mother's side, he had both Danish and Scottish ancestors. His great-grandfather, Andrew Chrystie (1697–1760), was born in Scotland. Andrew moved to Norway in 1717. His daughter, Jacobine Chrystie (1746–1818), married Henrik Arnold Thaulow (1722–1799). He was the father of Wergeland's mother, Alette Thaulow (1780–1843). Wergeland got his first name from the elder Henrik Arnold.

His ancestors with the Wergeland name lived on a farm called Verkland in Norway. The name "Wergeland" is a Danish way of writing "Verkland."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Henrik Arnold Wergeland para niños

In Spanish: Henrik Arnold Wergeland para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |