German colonial empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

German colonial empire

|

|

|---|---|

| 1884–1920 | |

German colonies and protectorates in 1914

|

|

| Status | Colonial empire |

| Capital | Berlin |

| Common languages |

|

| History | |

| 1884 | |

|

• Abushiri revolt

|

1888 |

|

• Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty

|

1890 |

|

• Adamawa Wars

|

1899 |

|

• Herero Wars

|

1904 |

| 1905 | |

| 1919 | |

|

• Disestablished

|

1920 |

| Area | |

| 1912 | 2,953,161 km2 (1,140,222 sq mi) |

| Population | |

|

• 1912

|

11,979,000 |

The German colonial empire (German: Deutsches Kolonialreich) was made up of the lands Germany controlled outside of Europe. Germany became a unified country in 1871. At first, its leader, Otto von Bismarck, didn't want colonies. But during the "Scramble for Africa" in 1884, Germany started claiming lands.

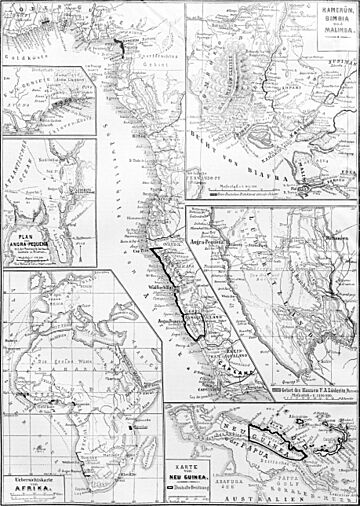

Soon, Germany had the third-largest colonial empire. Only the British and French empires were bigger. German colonies were in parts of Africa, like present-day Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Namibia, Cameroon, and Togo. They also had islands in the Pacific, such as New Guinea and Samoa.

Germany lost control of most colonies when the First World War began in 1914. Some German forces in German East Africa fought until the war ended. After Germany lost the war, its colonies were taken away. This was part of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Each colony became a League of Nations mandate, managed by one of the Allied powers.

Contents

- Germany's Early Steps Towards Colonies (Before 1884)

- Germany's Colonial Empire Begins (1884–1890)

- The Empire Under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1890–1914)

- End of the German Colonial Empire (1914–1918)

- Colonialism After 1918

- Administration and Policies

- Legacy of German Colonialism

- List of German Colonies (as of 1912)

- See also

Germany's Early Steps Towards Colonies (Before 1884)

Germans had a long history of trading by sea, like the Hanseatic League. German traders and missionaries were interested in lands far away. Trading companies from cities like Hamburg and Bremen made deals with local leaders in Africa and the Pacific. These agreements later helped Germany claim these lands.

However, before Germany became one country in 1871, its states didn't have strong navies. A strong navy was needed to protect and supply colonies far away. German leaders, like Otto von Bismarck, focused on uniting Germany in Europe.

Early Attempts at Colonization (1815–1871)

Some private groups in Germany wanted colonies in the 1840s. For example, the Hamburg Colonial Society tried to buy the Chatham Islands near New Zealand. But Great Britain already claimed them. Another group tried to create a "New Germany" in Texas, but it failed badly.

From the 1850s, German businesses started trading in areas that later became German colonies. These included parts of West Africa, East Africa, the Samoan Islands, and New Guinea.

In 1859, Prussia tried to claim Formosa (modern Taiwan). A Prussian naval trip went there to make trade deals and take the island. But their forces were too small, and they didn't want to upset trade talks with Qing China. So, they didn't claim Formosa.

Bismarck's Early Views on Colonies (1862–1871)

Bismarck, Germany's powerful leader, was against having colonies at first. He thought colonies cost too much and didn't offer many benefits. He believed Germany should focus on its own security in Europe.

He once wrote that the benefits of colonies were "mostly imaginary." He also said that the costs of setting up and protecting colonies were often higher than any good they brought. Bismarck famously said, "I am no man for colonies."

Instead of colonies, Germany wanted naval bases to protect its trade ships. In 1869, the navy set up its first permanent overseas base in Yokohama, Japan. This base was useful later when Germany got colonies in the Pacific.

Debates and Small Steps (1871–1878)

After Germany became a unified empire in 1871, people started talking more about colonies. Groups were formed to promote the idea. They argued that colonies would:

- Provide new markets for German goods.

- Give Germans a place to move to, so they wouldn't be "lost" to other countries.

- Allow Germany to spread its culture.

- Help solve social problems at home by giving people a national goal.

However, Bismarck still preferred informal trade. He didn't want to take over lands or build new states. So, Germany's first steps were very careful. They signed a friendship treaty with Tonga in 1876 for a coal station. In 1878, a German ship briefly claimed parts of Samoa, but this was changed to a friendship treaty later.

Germany's Colonial Empire Begins (1884–1890)

Even though Bismarck was still unsure about colonies, he agreed to get some in 1884. He wanted to protect German trade, get raw materials, and find new markets. Germany quickly became the third-largest colonial power. Bismarck put many German trading posts under the protection of the German Empire.

How Germany Gained Colonies (1884–1888)

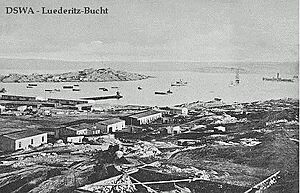

In April 1884, a trading post in Lüderitz Bay and its surrounding area in southwest Africa became German South West Africa. In July, Togoland and parts of Cameroon were claimed. Then came the northeastern part of New Guinea (called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland) and nearby islands (the Bismarck Archipelago).

In January 1885, the German flag was raised in Kapitaï and Koba in West Africa. In February, a German explorer named Carl Peters claimed huge areas in East Africa for his company. These lands became German East Africa. Local rulers often signed treaties without fully understanding them. They traded vast lands for small payments or promises of protection.

German forces often used harsh methods to control these new lands. They fought against local freedom fighters. By 1885, Germany had largely completed its first wave of colonial claims.

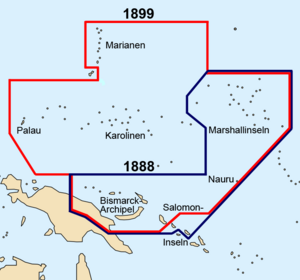

Later, in October 1885, Germany claimed the Marshall Islands and some of the Solomon Islands. In 1888, Germany took over Nauru after helping end a civil war there.

Why Bismarck Changed His Mind

Historians still debate why Bismarck suddenly decided to get colonies. Some say it was due to public pressure in Germany. Others believe it was to improve Germany's standing among other powerful nations. Bismarck also wanted to strengthen his political position at home.

Company Rule and Its Problems

Bismarck preferred that private companies manage the colonies to save government money. He gave these companies official protection and control over trade and administration. Examples include the German East Africa Company and the German New Guinea Company.

However, this plan didn't work well. The companies often struggled financially. Also, local people revolted because of unfair treatment. This forced Bismarck and later German leaders to take direct control of the colonies.

German forces often used brutal methods to put down these revolts. They destroyed villages and crops, forcing people to flee. This caused lasting damage to the land and its people.

Stopping New Acquisitions (1888–1890)

After 1885, Bismarck stopped trying to get more colonies. He wanted to keep good relationships with Britain and France. He even considered giving up some colonies because they were a burden.

Bismarck used colonies as bargaining chips. At the Congo Conference in Berlin (1884–1885), he helped divide Africa among the Great Powers. In 1890, he signed the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty with Britain. Germany gave up some claims in East Africa in exchange for the Caprivi Strip, which connected German South West Africa to the Zambezi River.

The Empire Under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1890–1914)

Kaiser Wilhelm II, who ruled from 1888 to 1918, wanted Germany to expand its colonial lands. He believed Germany, as a "late-comer," needed its "place in the Sun." This meant having colonies and a say in global affairs. This new "Weltpolitik" (Global Policy) was about national pride, unlike Bismarck's more practical approach.

New Colonies After 1890

After 1890, Germany gained only a few smaller territories. In 1897, after two German missionaries were killed, Kaiser Wilhelm sent ships to occupy Jiaozhou Bay in China. This became the Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory, and Germany gained mining and railway rights in the area.

In 1899, Germany bought the Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands, and Palau in Micronesia from Spain. The western part of the Samoan islands also became a German protectorate. Germany also expanded its control inland in existing colonies, adding the kingdoms of Burundi and Rwanda to German East Africa.

In 1911, during the Agadir Crisis, Germany gained parts of French Congo. These were added to German Cameroon and called Neukamerun. This aggressive colonial policy made other powerful nations wary of Germany.

Anticolonial Resistance (1897–1905)

German colonial rulers often forced local people into unfair agreements. This led to tribes losing their land and power, and some were forced into labor. The Germans wanted to create colonies mainly for white settlers.

Local people often used guerrilla tactics against the Germans. The Germans responded harshly, destroying villages and crops. This forced populations to flee into harsh areas, where many died from starvation.

The most serious conflicts were:

- Reprisals against the Chinese after the Boxer Rebellion (1901–1902).

- The Herero and Namaqua genocide (1904–1905) in South West Africa.

- The suppression of the Maji Maji Rebellion (1905–1907) in East Africa.

In South West Africa, the Herero and Nama revolted in 1904. German forces, led by Lieutenant-General Lothar von Trotha, defeated them. Von Trotha ordered the surviving Herero into the desert, leading to thousands of deaths. This event is considered the first genocide of the 20th century.

The Maji-Maji rebellion in German East Africa also led to an estimated 100,000 deaths, many from famine caused by German tactics.

New Colonial Policies (1905–1914)

After the brutal colonial wars, Germany decided to change its approach. In 1907, the Colonial Department became its own ministry, the Imperial Colonial Office. Bernhard Dernburg, a banker, led this new office. He removed incompetent officials and brought in new, more humane ones.

Dernburg visited the colonies to understand their problems. He encouraged banks to invest in them. Large-scale projects like railways were built. Cities like Dar es Salaam and Lomé became modern and well-developed.

Dernburg also focused on improving the lives of local people. Corporal punishment was stopped. Schools and hospitals were built. He said that the local population was "the most important factor in our colonies."

After 1905, there were no more major revolts. The colonies became more economically successful. Trade between Germany and its colonies grew significantly. By 1914, most colonies were becoming financially independent.

-

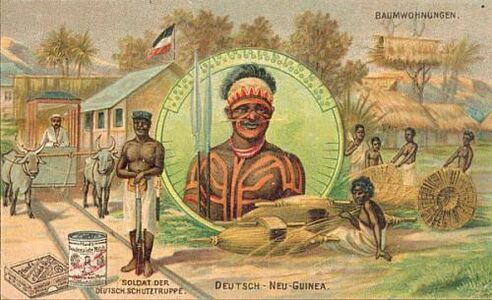

Postcards showed romantic images of natives and exotic places, like this early 20th-century card of the German colonial territory in New Guinea.

End of the German Colonial Empire (1914–1918)

Conquest During World War I

When World War I began in July 1914, Britain and its allies quickly attacked Germany's colonies. The public was told that German colonies were a threat because they had powerful wireless stations.

The German colonies fought hard, but by 1916, Germany had lost most of them. Only German East Africa, led by General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, held out against the Allies until the war's end.

In the Pacific, Japan, Britain's ally, quickly took Germany's island colonies. German Samoa fell to New Zealand without a fight. Australia took over German New Guinea within weeks.

Confiscation of Colonies

After Germany's defeat in World War I, its overseas empire was taken apart. The Treaty of Versailles officially turned German colonies into League of Nations mandates. These were divided among Belgium, the United Kingdom, its Dominions, France, and Japan. The Allies made sure none of these lands would ever be returned to Germany.

In Africa, Britain and France divided German Kamerun and Togoland. Belgium received Ruanda-Urundi from German East Africa. The United Kingdom gained most of German East Africa, connecting its possessions from South Africa to Egypt. Portugal received a small part of German East Africa. German South West Africa was given to the Union of South Africa.

In the Pacific, Japan received Germany's islands north of the equator and Kiautschou in China. German Samoa went to New Zealand. German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Nauru became mandates of Australia.

The Allies believed their rule was better than Germany's. They didn't consider giving these colonies independence.

Colonialism After 1918

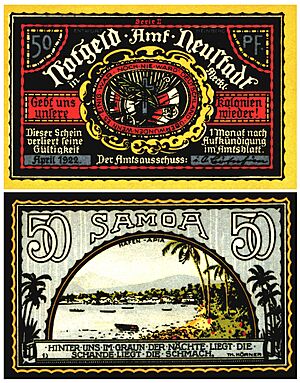

After World War I, many Germans felt it was wrong to take their colonies. They believed Germany had a right to them. In 1919, almost all German political parties voted for a resolution demanding the return of the colonies. However, this protest didn't change anything. Germany had to give up all its colonies. Most Germans had to leave the colonies, except for some descendants of settlers in German Southwest Africa (now Namibia).

Weimar Republic (1919–1933)

Even during the Weimar Republic, some German politicians called for the colonies to be returned. A Colonial Office was set up in the Foreign Office in 1924. In 1925, a group called the "Interparty Colonial Union" was formed, with members from across the political spectrum. Some German settlers even returned to their plantations in Cameroon.

Many Germans didn't accept the idea that Germany was solely to blame for the war. They saw the taking of their colonies as theft.

Nazi Period (1933–1945)

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party sometimes mentioned getting the lost colonies back. But their main goal was to gain land in Eastern Europe. The Nazis created an Office of Colonial Policy in 1934 to promote pro-colonial ideas. However, no new overseas colonies were acquired. By 1943, the organization was disbanded because its activities were "irrelevant to the war." The Nazi government focused on expanding within Europe.

Administration and Policies

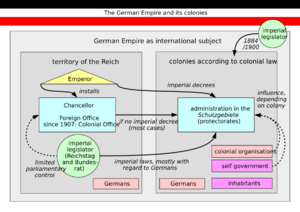

Colonial Administration Structure

From 1890 to 1907, the colonies were managed by the Colonial Division of the Foreign Office. In 1907, this became a separate ministry, the Imperial Colonial Office. The port of Kiautschou was managed by the Imperial Naval Office, not the Colonial Office.

Each colony had a Governor, helped by secretaries and other officials. Colonies were divided into districts, each run by a District Officer. Some areas, called "Residencies," allowed local rulers more power to keep German costs low.

Military forces called Schutztruppen were stationed in Cameroon, Southwest Africa, and East Africa for security. Police forces were also organized like military troops.

German law applied to Europeans in the colonies. For local people, the Kaiser initially held all law-making power. Over time, colonial officials were given authority to manage local laws. This meant there were different laws for Europeans and local people.

Local people in the colonies were not considered German citizens. They were seen as subjects or wards of Germany. They had fewer rights than Europeans. For example, they couldn't appeal court decisions made by colonial authorities.

Education and Healthcare

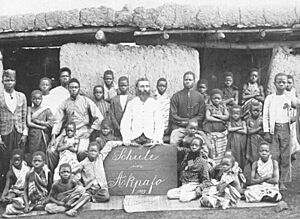

German colonizers often viewed local populations as "children" who needed to be educated and guided. German missionary groups, both Protestant and Catholic, set up schools and taught local people basic education, modern farming, and Christianity.

Missionaries often protested against the abuse of local people by colonial administrators and plantation owners. They also ran their own plantations to support themselves.

German scientists like Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich did important research on tropical diseases, which was shared worldwide. Millions of Africans were vaccinated against smallpox. German medical discoveries helped treat diseases like sleeping sickness.

However, some German scientists, like Eugen Fischer, conducted unethical medical experiments on local people, especially children, in concentration camps during the Herero genocide. These experiments were based on racist ideas about "racial purity."

Social Darwinism and Its Impact

Social Darwinism was a theory that applied "survival of the fittest" to human groups and races. Many German intellectuals believed this theory. It was used to justify Germany's right to acquire colonies and compete with other world powers. German colonial rule often used violence, claiming it was for 'culture' and 'civilization'.

Some German doctors and administrators wanted to increase the native population to have more laborers. But some, like Eugen Fischer, believed that once their usefulness was gone, Europeans should "allow free competition," which he thought meant their end.

The Duala people in Cameroon welcomed German rule. Many converted to Protestantism and learned German. Colonial officials preferred them as clerks in German offices.

Legacy of German Colonialism

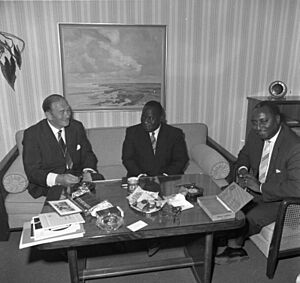

After World War II, regaining former colonies was not a major goal for West Germany. However, some German politicians suggested managing trusts in Tanganyika or Togo.

Today, the German language is not an official language in any country outside Europe. However, in Namibia, it is a recognized national language. There are many German place names and buildings there. A German ethnic minority of about 30,000 people still lives in Namibia.

After World War II, many independence activists in Tanganyika were sons of Schutztruppe soldiers who fought for Germany. They often visited their fathers' former commander, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, for advice.

When West Germany's Goethe Institute was founded to promote German language and culture, its first foreign branches in 1961 were in the former German colonies of Cameroon and Togo. Tanzania also opened a Goethe Institute branch after gaining independence.

In Rwanda, some people looked back at German colonial rule more positively than the later Belgian rule. Close ties with West Germany were re-established after Rwanda's independence. The German language is still popular in these countries, and some German words are used in the Tanzanian dialect of Kiswahili.

List of German Colonies (as of 1912)

| Territory | Capital | Established | Disestablished | Area | Total population | German population | Current countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamerun Kamerun |

Jaunde | 1884 | 1920 | 495,000 km2 | 2,540,000 | 1,359 | |

| Togoland Togo |

Bagida (1884–87) Sebeab (1887–97) Lomé (1897–1916) |

1884 | 1920 | 87,200 km2 | 1,003,000 | 316 | |

| German South West Africa Deutsch-Südwestafrika |

Windhuk (from 1891) | 1884 | 1920 | 835,100 km2 | 86,000 | 12,135 | |

| German East Africa Deutsch-Ostafrika |

Bagamoyo (1885–1890) Dar es Salaam (1890–1916) Tabora (1916, temporary) |

1891 | 1920 | 995,000 km2 | 7,511,000 | 3,579 | |

| German New Guinea Deutsch-Neu-Guinea Including Imperial German Pacific Protectorates:

|

Finschhafen (1884–1891) Madang (1891–1899) Herbertshöhe (1899–1910) Simpsonhafen (1910–1914) |

1884 | 1920 | 242,776 km2 | 601,000 | 665 | |

| German Samoa Deutsch-Samoa |

Apia | 1899 | 1920 | 2,570 km2 | 38,000 | 294 | |

| Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory Pachtgebiet Kiautschou |

Tsingtau | 1897 | 1920 | 515 km2 | 200,000 | 400 | |

| Total (as of 1912) | 2,658,161 km2 | 11,979,000 | 18,748 | 22 |

See also

Colonialism

- Brandenburger Gold Coast

- Cologne in the German colonial empire

- Duala people

- German colonial projects before 1871

- German colonization of the Americas

- German East Africa Company

- German New Guinea Company

- History of German foreign policy

- Imperial Colonial Office

- List of former German colonies

- Reichskolonialbund

- Wilhelminism

Post-Colonialism

- Cameroon–Germany relations

- GDR Children of Namibia

- German Academic Exchange Service

- German language in Namibia

- Germany–Namibia relations

- Germany–Rwanda relations

- Germany–Tanzania relations

- Germany–Togo relations

- Goethe Institute

- Kandt House Museum

- Unserdeutsch

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |