Paul Ehrlich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Ehrlich

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 14 March 1854 |

| Died | August 20, 1915 (aged 61) Bad Homburg, Hesse, German Empire

|

| Citizenship | German |

| Known for | Chemotherapy Immunology Basophil Magic bullet Mast cell Receptor theory Side-chain theory Ehrlich's reagent |

| Spouse(s) | Hedwig Pinkus (1864–1948) (m. 1883; 2 children) |

| Children | Stephanie and Marianne |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine (1908) Cameron Prize of the University of Edinburgh (1914) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Immunology |

| Thesis | Beiträge zur Theorie und Praxis der histologischen Färbung (1878) |

| Notable students | Hans Schlossberger |

| Signature | |

|

|

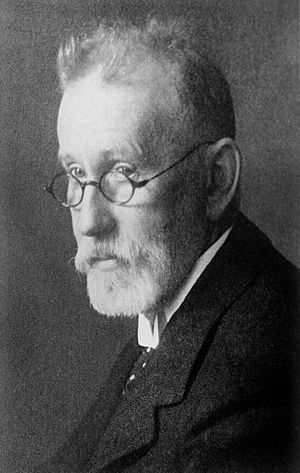

Paul Ehrlich (14 March 1854 – 20 August 1915) was a German doctor and scientist. He won a Nobel Prize for his important work. He studied blood diseases (called hematology), how the body fights sickness (called immunology), and how to use chemicals to treat infections (called antimicrobial chemotherapy).

One of his big achievements was creating a way to stain bacteria. This method helped doctors see different types of blood cells. This led to better ways to find and treat many blood diseases.

His lab found a medicine called arsphenamine (also known as Salvarsan). This discovery started the idea of "chemotherapy," which means using chemicals to treat diseases. Ehrlich also made popular the idea of a "magic bullet." This was a medicine that would only attack the germs causing a disease, without harming the patient. He also helped create a medicine to fight diphtheria and found a way to make sure medicines were always the same strength.

In 1908, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This was for his amazing work in immunology. He also started and was the first director of the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Germany. This institute still works on vaccines and medicines today. A type of bacteria, Ehrlichia, is named after him.

Contents

Paul Ehrlich's Life Story

Paul Ehrlich was born on March 14, 1854. This was in a town called Strehlen, which was part of Prussia. Today, this town is called Strzelin and is in Poland. He was the second child in his family. His father was a leader in the local Jewish community.

Paul went to a good school in Breslau (now Wrocław). There, he met Albert Neisser, who also became a famous doctor. Even as a schoolboy, Paul loved staining tiny things to look at them under a microscope. This interest stayed with him through his medical studies. He studied at universities in Wroclaw, Strasbourg, Freiburg, and Leipzig.

After becoming a doctor in 1882, he worked in Berlin. He focused on studying tissues, blood, and how colors (dyes) worked.

In 1883, he married Hedwig Pinkus in Prudnik, Poland. They had two daughters, Stephanie and Marianne. Hedwig's brother, Max Pinkus, owned a textile factory. Paul lived in the Fränkel family's villa in Neustadt (now Prudnik).

After finishing his medical training in Berlin in 1886, Ehrlich traveled. He went to Egypt and other countries in 1888 and 1889. He did this partly to get better from tuberculosis he caught in his lab. When he came back, he opened his own small lab and medical practice in Berlin.

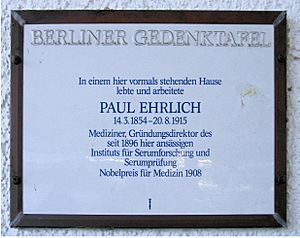

In 1891, Robert Koch invited Ehrlich to work at his Institute of Infectious Diseases in Berlin. In 1896, a new part of the institute was created just for Ehrlich's work. It was called the Institute for Serum Research and Testing. Ehrlich became its first director.

In 1899, his institute moved to Frankfurt am Main. It was renamed the Institute of Experimental Therapy. Here, in 1909, he made a huge discovery: Salvarsan. This was the first medicine designed to target a specific germ. In 1914, he received an award from the University of Edinburgh. Two other Nobel Prize winners, Henry Hallett Dale and Paul Karrer, worked with him. The institute was renamed the Paul Ehrlich Institute in his honor in 1947.

Paul Ehrlich died on August 20, 1915, after a heart attack. The German emperor, Wilhelm II, sent a message saying how much he admired Ehrlich's work. Paul Ehrlich was buried in the Old Jewish Cemetery in Frankfurt.

Ehrlich's Amazing Discoveries

Staining Blood Cells

In the 1870s, Ehrlich's cousin, Karl Weigert, was the first to use dyes to stain bacteria. He also used special colors to study tissues and find bacteria. Ehrlich continued this work while studying in Strassburg. He was very interested in how dyes could make tiny parts of cells visible.

In 1878, he earned his doctorate degree. His research was about how to stain tissues for microscopic study.

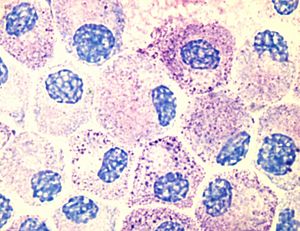

One of his most important discoveries was a new type of cell. Ehrlich found tiny grains inside certain cells. He could see these grains using a special dye. He thought these cells were well-fed, so he called them mast cells. This name comes from the German word for fattening animals. His focus on chemistry was unusual for a medical student at that time.

At the Charité hospital, Ehrlich improved how white blood cells were identified. He found a way to dry blood samples on glass slides and then heat them. This made the cells stick so they could be stained. He used different types of dyes. For the first time, he could tell apart different kinds of white blood cells. He could see lymphocytes, mono- and poly-nuclear cells, eosinophils, and mast cells.

From 1880, Ehrlich also studied red blood cells. He found red blood cells that had a nucleus. He also found the cells that grow into red blood cells. His work helped doctors understand different types of anemia (when you don't have enough healthy red blood cells). He also helped classify different types of leukemia (cancers of the white blood cells).

In 1881, he published a new urine test. This test could tell the difference between typhoid fever and simple diarrhea. The color of the stain helped predict how serious the disease was. The dye solution he used is still known as Ehrlich's reagent today.

Ehrlich's big achievement was connecting chemistry, biology, and medicine. This was new, and some doctors didn't understand his work. This made it hard for him to find a suitable job as a professor.

Understanding Immunity

Working with Robert Koch

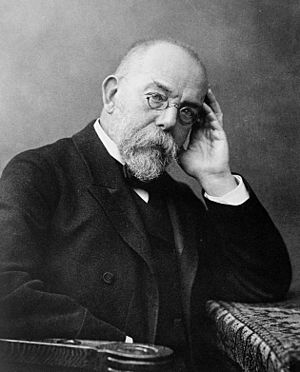

When Ehrlich was a student, he met Robert Koch. Koch was a doctor who discovered the germ that causes anthrax. In 1882, Ehrlich was there when Koch announced he had found the germ that causes tuberculosis. Ehrlich called this his "greatest experience in science." The very next day, Ehrlich improved Koch's staining method, and Koch liked it. From then on, they were good friends.

In 1891, Koch invited Ehrlich to work at his new Institute of Infectious Diseases in Berlin. Koch couldn't pay him, but he gave Ehrlich full access to his lab, patients, and supplies. Ehrlich was always thankful for this.

Early Immunity Research

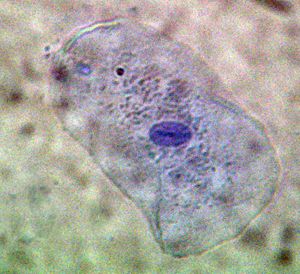

Ehrlich started his first experiments on how the body becomes immune to sickness in his own lab. He gave mice small, increasing amounts of poisons like ricin. He found that the mice became "ricin-proof." This meant they were immune. He noticed this immunity started quickly and lasted for months. But mice immune to ricin were still sensitive to other poisons.

He also studied how immunity might be passed down. He found that baby mice got antibodies from their mothers through milk. This showed how mothers could protect their babies from poisons.

Ehrlich also looked into autoimmunity. This is when the body's immune system attacks its own healthy tissues. He believed the body had ways to stop this from happening. He called it "horror autotoxicus," meaning "fear of self-poisoning."

Working with Behring on Diphtheria Medicine

Emil von Behring was working on a medicine to treat diphtheria and tetanus. Koch suggested that Behring and Ehrlich work together. Ehrlich helped make the animals much more immune. In 1894, tests with the diphtheria medicine worked well. A company called Hoechst started selling it.

Ehrlich felt he didn't get enough credit for his part in developing the diphtheria medicine. He and Behring had problems, and Ehrlich refused to work with him after 1900. Behring alone received the first Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1901 for his work on diphtheria.

Standardizing Medicines

Medicines like antiserums were new, and their quality varied a lot. So, Germany started a system to make sure they were safe and worked well. From 1895, only government-approved serums could be sold. Ehrlich became the director of the Institute for Serum Research and Testing in Berlin in 1896.

To check how well diphtheria antiserum worked, Ehrlich needed a stable amount of diphtheria toxin. He found that the toxin spoiled. So, he used a special serum powder from Behring as a standard. He mixed the toxin and serum so they would cancel each other out. He made sure the test animal would die after four days if the serum was too weak. This made testing very accurate, like a chemical titration. This showed his desire to measure things precisely in biology.

In 1899, Ehrlich's institute moved to Frankfurt and was renamed the Royal Prussian Institute of Experimental Therapy. Other countries copied Germany's quality control methods. They also got their standard serum from Frankfurt. After diphtheria antiserum, other medicines for tetanus and animal diseases were developed and tested there. Ehrlich's important colleague was Julius Morgenroth.

Ehrlich's Side-Chain Theory

Ehrlich believed that cells had special parts called "side chains." These side chains could grab onto toxins (poisons). If the body survived the toxin, new side chains would grow. If the cell made too many side chains, they could be released into the blood as antibodies.

He expanded this theory, using terms like "receptors." He thought there was another immune molecule between the germ and the antibody.

For his theories on immunity and his work on standardizing serums, Ehrlich won the Nobel Prize in 1908. He shared it with Élie Metchnikoff, who studied how cells eat germs (phagocytosis).

Fighting Cancer

In 1901, Ehrlich faced budget cuts. A kind person named Georg Speyer helped him. Speyer's widow, Franziska Speyer, funded the Georg-Speyer House for cancer research next to Ehrlich's institute. The German Emperor Wilhelm II also asked Ehrlich to focus on cancer. Ehrlich told his sponsors that finding a cure would take a long time.

Ehrlich and his team found that when tumor cells were grown and moved, they became more harmful over time. If the main tumor was removed, the cancer spread much faster. Ehrlich used methods from studying bacteria to research cancer. He tried to make the body immune to cancer by injecting weakened cancer cells. He also brought in the idea of "Big Science," where many people work together on a large research project.

Chemotherapy: Chemical Cures

Staining Living Tissues

In 1885, Ehrlich wrote about how living things use oxygen. He introduced a new way to stain living tissues. He found that dyes could be easily taken in by living things if they were in tiny grains. He injected dyes into animals. After they died, he saw that different organs were colored differently. This work showed his belief that all life processes are based on chemical changes in cells.

Methylene Blue

Ehrlich found methylene blue, a dye he thought was great for staining bacteria. Robert Koch also used it to study tuberculosis germs. Ehrlich also noticed that methylene blue stained nerve cells. He thought this was a big discovery for studying the brain and nerves.

When Ehrlich was unemployed, he kept working on methylene blue. He thought if it stained germs, maybe it could kill them. Since the germs that cause malaria could be stained with methylene blue, he thought it might treat malaria. He treated two patients, and their fever went down, and the malaria germs disappeared from their blood. This started his long work with a chemical company called Hoechst.

The Search for a "Magic Bullet"

Ehrlich moved his research on chemical treatments to the Georg-Speyer House. He wanted to find a medicine that worked as well as methylene blue but without side effects. He believed there should be chemical medicines that could specifically target diseases, just like serums did. His goal was to find a "Therapia sterilisans magna"—a treatment that could kill all disease-causing germs.

Ehrlich used guinea pigs with a disease called trypanosoma as a model. He tested many chemicals. He found that a dye called trypan red could kill the trypanosomes. From 1906, he studied a chemical called atoxyl. He had Robert Koch test it during a trip to Africa. Atoxyl could cause harm, especially to the eyes. Ehrlich developed a way to systematically test many chemicals, like how drug companies do today. He found a chemical called Compound 418 that worked very well.

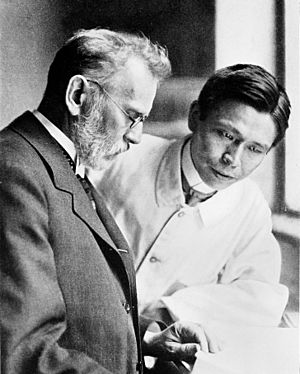

With his assistant Sahachiro Hata, Ehrlich discovered in 1909 that Compound 606, called Arsphenamine, fought against spiral-shaped bacteria called spirochaetes.

After many tests, the Hoechst company started selling it in 1910 as Salvarsan. This was the first medicine created based on scientific ideas to have a specific effect. Salvarsan worked amazingly well, especially compared to older treatments. It became a very popular medicine. Salvarsan was later improved and replaced by Neosalvarsan in 1911. Ehrlich's work also hinted at the existence of the blood-brain barrier, which protects the brain.

The medicine caused some controversy. Ehrlich was accused of getting too rich. Also, another scientist claimed he discovered the drug first. Some people died during the tests, and Ehrlich was blamed. In 1914, the person who accused him was found guilty of lying. Even though Ehrlich was cleared, the stress made him very sad.

The Magic Bullet Idea

Ehrlich believed that if a chemical could be made to target only the germ causing a disease, then a poison for that germ could be delivered right to it. This would create a "magic bullet" (he called it Zauberkugel). This "magic bullet" would kill only the target germ and not harm the patient. Today, this idea has come true with medicines that link antibodies (which target specific cells) to powerful drugs. These new medicines can deliver drugs directly to cancer cells, for example.

Ehrlich's Lasting Impact

In 1910, a street in Frankfurt was named after Ehrlich. During Nazi Germany, Ehrlich's achievements were ignored because he was Jewish. The street was renamed. But after the war, it was changed back to Paul-Ehrlich-Strasse. Many German cities now have streets named after him.

West Germany released a postage stamp in 1954 to celebrate 100 years since Paul Ehrlich and Emil von Behring were born.

The 200 Deutsche Mark banknote, used until 2001, featured Paul Ehrlich's picture.

The German Paul Ehrlich Institute, which is the successor to his earlier institutes, was named after him in 1947.

Many schools and pharmacies are named after him. There is also a Paul Ehrlich Society for Chemotherapy and a Paul Ehrlich Clinic. The Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize is a very important German award for medical research.

A crater on the moon was named after Paul Ehrlich in 1970.

Ehrlich's life was shown in the 1940 American movie Dr. Ehrlich's Magic Bullet. Edward G. Robinson played Paul Ehrlich. The movie focused on his discovery of Salvarsan.

Awards and Titles

- 1882: Given the title of Professor.

- 1890: Appointed a special Professor at Humboldt University.

- 1896: Given the title of Medical Councillor.

- 1903: Received Prussia's highest science award, the Great Golden Medal of Science.

- 1904: Became an honorary professor at the University of Göttingen. Also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Chicago.

- 1907: Given the title Senior Medical Councillor. Also received an honorary doctorate from Oxford University.

- 1908: Won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his "work on immunity."

- 1911: Given Prussia's highest civilian award, Privy Councillor.

- 1912: Made an honorary citizen of Frankfurt and his hometown, Strehlen.

- 1914: Awarded the Cameron Prize from the University of Edinburgh.

- 1914: Appointed full Professor of Pharmacology at the new Frankfurt University.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Paul Ehrlich para niños

In Spanish: Paul Ehrlich para niños

- Ehrlich's reagent

- German inventors and discoverers

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |