Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck

|

|

|---|---|

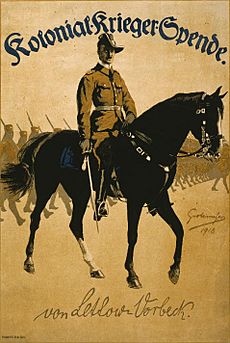

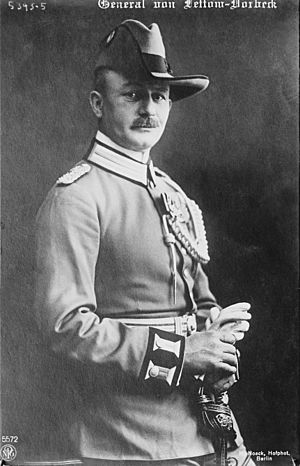

Lettow-Vorbeck in 1914

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Der Löwe von Afrika The Lion of Africa |

| Born | 20 March 1870 Saarlouis, Rhine Province, Prussia |

| Died | 9 March 1964 (aged 93) Hamburg, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1890–1920 |

| Rank | General der Infanterie |

| Unit | 4th Foot Guards Schutztruppe of German South-West Africa XI Corps |

| Commands held | 2nd Sea Battalion Schutztruppe of German East Africa |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Pour le Mérite with Oak Leaves |

| Other work | Public speaker, writer |

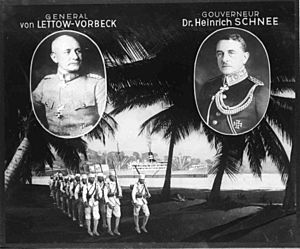

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck (born March 20, 1870 – died March 9, 1964) was a German general. He was known as the Lion of Africa (Löwe von Afrika). He commanded the German forces in German East Africa during World War I.

For four years, he led a small force of about 14,000 soldiers (3,000 Germans and 11,000 Africans). They fought against a much larger force of 300,000 British, Indian, Belgian, and Portuguese troops. Lettow-Vorbeck was never truly defeated in battle. He was the only German commander to successfully invade a part of the British Empire during the war. His actions are often called one of the most successful guerrilla operations in history.

Contents

Early Life and Military Start

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck was born in Saarlouis, a town in Prussia. His father was an army officer. Paul went to boarding schools in Berlin and joined the cadet corps, which is like a military school for young people. In 1890, he became a Lieutenant in the Imperial German Army.

He spent about ten years as a junior officer. He remembered early morning inspections, army training, and seeing important leaders like the Kaiser (German Emperor). He also enjoyed card games and dances in Berlin.

Lettow-Vorbeck was later assigned to the Great German General Staff, a group of high-ranking military planners.

Military Career in Africa and China

In 1900, Lettow-Vorbeck went to China. He was part of an international force that helped stop the Boxer Rebellion. He found Chinese culture interesting, but he did not like fighting against guerrillas. He felt it was bad for army discipline. He returned to Germany in 1901.

Starting in 1904, Lettow-Vorbeck, now a captain, was sent to German Southwest Africa (which is now Namibia). He fought in the Herero Wars against the Herero people. He took part in the Battle of Waterberg.

Later, the Nama people also rebelled. Lettow-Vorbeck stayed to fight them. He was injured in 1906 during a gunfight, losing sight in his left eye and getting hurt in his chest. He had to go to South Africa for treatment.

During his time in Southwest Africa, he learned important skills from the local people. He learned how to survive in the wilderness, how to live off the land, and how to keep going without much food or water. These skills would be very useful to him later.

In 1907, he was promoted to Major. From 1909 to 1913, he commanded a marine battalion. In October 1913, he became a Lieutenant Colonel. He was supposed to command German colonial forces in German Kamerun (now Cameroon). But his orders changed, and in April 1914, he was sent to German East Africa (now Tanzania).

On his way there, he became good friends with the Danish writer Karen Blixen. She later said he reminded her of what Imperial Germany stood for.

World War I in East Africa

When World War I began, Lettow-Vorbeck had a clear plan. He knew that East Africa was not the main battleground. His goal was to keep as many British troops busy in Africa as possible. This would stop them from fighting on the main battlefields in Europe.

In August 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck commanded about 2,600 German soldiers and 2,472 African soldiers, called Askari. He decided to act first, even though the colony's governor wanted to stay neutral. On November 2, 1914, the British attacked the city of Tanga. For four days, German forces fought the Battle of Tanga and won.

Lettow-Vorbeck then attacked British railways. On January 19, 1915, he won another victory at Jassin. These wins helped the Germans get needed weapons and supplies. They also boosted the soldiers' spirits. However, they lost many experienced men, which was hard to replace.

Lettow-Vorbeck kept fighting British forces, even with high casualties. He led raids into British East Africa (now Kenya, Uganda, and Zanzibar). He targeted forts, railways, and communication lines. He hoped to force the Allies to send more soldiers away from Europe. He used everything he had to keep his troops supplied.

The Schutztruppe (protectorate force) grew to about 14,000 soldiers, mostly Askaris. Lettow-Vorbeck spoke Swahili, which earned him the respect of his African soldiers. He even appointed black officers and said, "we are all Africans here."

In 1915, he got more men and artillery from the German cruiser SMS Königsberg. The ship had been sunk, but its guns were moved to land. These became the largest guns used in the East African campaign.

In March 1916, British and Belgian forces launched a large attack with 45,000 men. Lettow-Vorbeck used the local climate and land to his advantage. He fought the British on his own terms. Even though he had to give up some land, he continued to resist. In October 1917, he fought a key battle at Mahiwa. He caused 2,700 casualties to the British, but he also lost 519 of his own men and ran low on ammunition. This forced him to retreat. After this battle, he was promoted to major-general.

Lettow-Vorbeck moved his troops south. They were on half rations, with the British following close behind. On November 25, 1917, his troops crossed the Ruvuma River into Portuguese Mozambique. This meant they were cut off from their old supply lines. They became a completely independent unit. On their first day in Mozambique, they attacked the Portuguese garrison at Ngomano and captured many supplies. They also captured a river boat with medical supplies, including medicine for malaria. For nearly a year, Lettow-Vorbeck's men lived off what they could capture from the British and Portuguese. They got new rifles, machine guns, and mortars.

The war in East Africa caused many problems for the local people. The fighting disrupted life and led to food shortages. Lettow-Vorbeck focused on his army's needs. He set up food storage areas along his march route, even if it meant nearby villages faced famine.

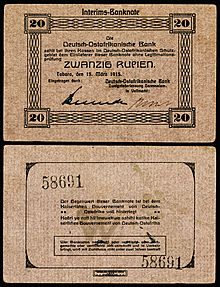

It was hard for Germany to send supplies to Lettow-Vorbeck because of the British naval blockade. Only two ships managed to get through. An attempt to resupply them by Zeppelin airship in November 1917 also failed. The airship turned back after getting a message that its landing area was no longer safe.

By late 1916, most of coastal German East Africa was under British control. The west was taken by Belgian forces. In December 1917, the German colony was officially declared an Allied protectorate.

Lettow-Vorbeck and his group, which included Europeans, Askaris, porters, women, and children, kept marching. They avoided the home areas of the African soldiers to prevent them from leaving. They traveled through very difficult land. The Allied commander, General Jan Smuts, decided to stop fighting the Schutztruppe directly. Instead, he went after their food supply.

Lettow-Vorbeck's tactics, while effective for his army, led to a severe famine that killed thousands of Africans. This also made the population weaker and more vulnerable to the Spanish flu epidemic that spread in 1918–1919.

Lettow-Vorbeck was highly respected by his officers, soldiers, and even by the Allied forces.

There is a story that Lettow-Vorbeck once lost his glass eye in the bush. When an Askari found it and asked why he took it out, Lettow-Vorbeck joked that he had put it there to watch them do their duty.

On September 28, 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed the Ruvuma River again and returned to German East Africa, with the British still following. He then went west into Northern Rhodesia. On November 13, 1918, two days after the war ended in Europe, he took the town of Kasama.

When he reached the Chambeshi River on November 14, a British officer told him about the Armistice (the end of the war). Lettow-Vorbeck agreed to stop fighting. This spot is now marked by the Chambeshi Monument in Zambia. He was told to march north to Abercorn to surrender his army, which he did on November 25. His army then consisted of 30 German officers, 125 German non-commissioned officers, 1,168 Askaris, and about 3,500 porters.

After the war, the German prisoners were sent to Dar es Salaam. Lettow-Vorbeck tried to get his Askaris released early from their prisoner-of-war camp.

Life After the War

Lettow-Vorbeck returned to Germany in March 1919 and was welcomed as a hero. He led his soldiers in a victory parade through the Brandenburg Gate. He was the only German commander to successfully invade the British Empire during World War I.

He stayed in the German army for a while. In 1920, he commanded troops that helped end the Spartacist Uprising in Hamburg. However, he lost his army position later that year because he was involved in the Kapp Putsch, a failed attempt to overthrow the government. After that, he worked in Bremen as an import-export manager.

In 1926, Lettow-Vorbeck met Richard Meinertzhagen, a British intelligence officer he had fought against. Three years later, he visited London and met Jan Smuts, a British general he had also fought. They became good friends.

Political Career

From 1928 to 1930, Lettow-Vorbeck served as a member of the Reichstag, which was the German parliament. He was part of a monarchist party (people who wanted a king or emperor). He left the party in 1930 when it moved further to the far right.

Lettow-Vorbeck did not trust Adolf Hitler or the Nazi movement. He even tried to form a group to oppose the Nazis.

During Nazi Germany

In 1935, Hitler offered him the job of ambassador to Great Britain. Lettow-Vorbeck refused this offer very coldly. Because of his refusal, he was watched closely, and his home office was searched. However, he was very popular with the German people. In 1938, at age 68, he was promoted to General for Special Purposes, but he was never called back to active duty.

One of his former officers, Theodor von Hippel, used his experiences from East Africa to create the Brandenburgers. This was a special commando unit during World War II.

After World War II

By the end of World War II, Lettow-Vorbeck had lost everything. His house was destroyed by bombs. For a time, he depended on food packages from his friends, Meinertzhagen and Smuts. After Germany's economy recovered, he became comfortable again. In 1953, he visited Dar-es-Salaam in Africa. Surviving Askaris welcomed him with their old marching song, Heia Safari!. British officials also greeted him with full military honors.

As African countries gained independence, some activists from Tanganyika (sons of his former Askaris) came to him for advice. Lettow-Vorbeck was happy to help them.

Personal Life and Death

After returning from Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck married Martha Wallroth in 1919. They had two sons and two daughters. Sadly, both of his sons and his stepson were killed fighting in the German army during World War II.

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck died in Hamburg in 1964, just before his 94th birthday. The West German government and army flew two former Askaris to attend his funeral as special guests.

Several army officers served as an honor guard. West Germany's Minister of Defence gave a speech, saying that Lettow-Vorbeck "was truly undefeated in the field." He was buried in Pronstorf, Germany.

Legacy and Recognition

In 1964, the West German parliament voted to give back-dated pay to all surviving Askaris who had served in the German forces during World War I. A special office was set up in Mwanza, Africa. Many former soldiers came, but only a few had the certificates Lettow-Vorbeck had given them in 1918. Others showed pieces of their old uniforms as proof. The German banker in charge had an idea: he asked each man to step forward, gave them a broom, and ordered them in German to perform military drills. Every man passed the test.

Four army barracks in Germany were once named after Lettow-Vorbeck. Today, only one remains, the Lettow-Vorbeck-Kaserne in Leer. The former Hamburg-Jenfeld barracks now has a "Tanzania Park" with large sculptures of Lettow-Vorbeck and his Askari soldiers.

In 2010, the city of Saarlouis renamed Von Lettow-Vorbeck-Straße (Lettow-Vorbeck Street) because of his involvement in the 1920 Kapp Putsch. In Hanover, "Lettow-Vorbeck Straße" was renamed "Namibia Straße." However, some streets in other German and Austrian cities are still named after him.

A type of dinosaur, Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki, was named after him.

Honors and Awards

He received many awards for his military service, including:

- Pour le Mérite (a very high military honor) with Oak Leaves

- Iron Cross, 1st and 2nd class

- Knight of the Military Order of Max Joseph

Works Written by Him

- Heia Safari! Deutschlands Kampf in Ostafrika (Heia Safari! Germany's Campaign in East Africa). 1920.

- Meine Erinnerungen aus Ostafrika (My Reminiscences of East Africa). 1920.

- Mein Leben (My Life). 1957.

See also

In Spanish: Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck para niños

In Spanish: Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck para niños

- German colonial empire

- Hermann Detzner

- Lettow

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |