East African campaign (World War I) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids East African campaign |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the African theatre of World War I | |||||||||

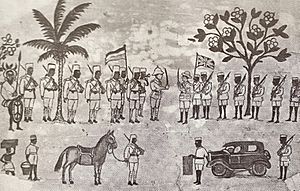

An Askari company ready to march in German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| British Empire Initially: 2 battalions 12,000–20,000 soldiers Total: 250,000 soldiers 600,000 porters |

Regulars (Schutztruppe) Initially: 2,700 Maximum: 18,000 1918: 1,283 Total: 22,000 Irregulars (Ruga-Ruga) 12,000+ |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

365,000 civilians died in war-related famines.

|

|||||||||

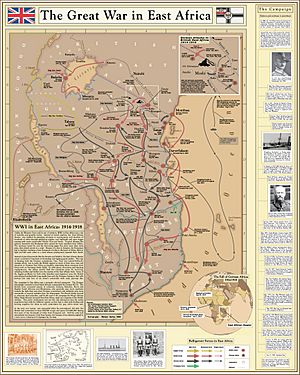

The East African campaign was a series of battles during World War I. It began in German East Africa (GEA). The fighting then spread to parts of Mozambique, Rhodesia, British East Africa, Uganda, and the Belgian Congo.

The main goal for the German forces was to distract the Allied armies. They wanted to pull Allied soldiers and supplies away from the main fighting in Europe. The German commander, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, led his troops in a clever guerrilla style. This meant they used surprise attacks and avoided big battles.

The fighting in East Africa continued for the entire war. The Germans finally surrendered on November 25, 1918. This was two weeks after the war ended in Europe. After the war, German East Africa was divided. It became new territories controlled by Britain and Belgium.

Contents

What was German East Africa?

German East Africa (called Deutsch-Ostafrika in German) was a colony of Germany. It was established in 1885. This large territory is now modern-day Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanzania.

About 7.5 million local people lived there. Only about 5,300 Europeans governed them. The German rule was generally stable. However, a big uprising called the Maji Maji Rebellion happened in 1904–1905.

The German military force in the colony was called the Schutztruppe. It had 260 Europeans and 2,470 African soldiers. There were also 2,700 white settlers who could join as reserve soldiers.

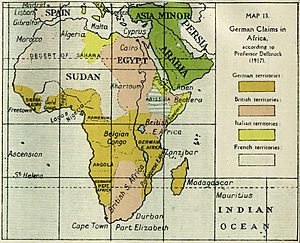

Germany's Big African Dream

When World War I started, Germany had a dream. They wanted to create a huge "German Central Africa" (Deutsch-Mittelafrika). This would involve taking over land, especially from the Belgian Congo. Their goal was to connect all their existing colonies. This would make Germany the most powerful colonial country in Africa.

However, the German military in Africa was not very strong. They had few soldiers and not enough good equipment. Many German soldiers used older weapons. The Allied forces in Africa also faced similar problems. Most colonial armies were meant to be local police. They were not ready to fight other countries. Still, German East Africa had the largest German military presence in Africa.

German War Strategy

The German commander, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, had a clear plan. He wanted to force the Allied powers to send troops and supplies to Africa. This would take away resources from the main war in Europe.

He planned to threaten the important British Uganda Railway. This would make the British invade German East Africa. Once they invaded, he would fight a defensive guerrilla campaign. This meant his smaller forces would use hit-and-run tactics. They would avoid direct, large-scale battles.

The Belgian Congo was neutral at first. But German ships attacked Belgian ports. This made Belgium decide to join the fight. Some Belgian officials saw this as a chance to expand their own territory. They hoped to gain land like Rwanda and Burundi.

Early Fighting (1914–1915)

First Attacks and British Response

At the start of the war, the governors of British and German East Africa wanted to stay neutral. But military leaders and their home governments wanted to fight. This caused some confusion.

On August 5, 1914, British troops from Uganda attacked German outposts. The British War Cabinet then decided to send soldiers from India. Their mission was to remove German bases.

On August 8, a British navy ship shelled the German city of Dar es Salaam. An agreement was made for a ceasefire. But the German commander, Lettow-Vorbeck, ignored it.

In August 1914, both sides prepared for war. The German Schutztruppe had about 260 Germans and 2,472 African soldiers (called Askari). The British had similar numbers. On August 15, German Askari launched their first attack. They captured Taveta from the British. German troops also attacked Portuguese outposts. This caused a diplomatic problem, as Portugal was not yet an Allied country.

In September, the Germans began raiding into British Kenya and Uganda. German ships on Lake Victoria caused some trouble. But the British quickly armed their own lake steamers. They turned them into makeshift gunboats. The British soon gained control of Lake Victoria.

To stop the German raids, the British planned a two-part invasion.

- One force of 8,000 troops would land at Tanga on November 2, 1914. They aimed to capture the city.

- Another force of 4,000 men would advance from British East Africa. They would attack Neu-Moshi on November 3.

The Germans, led by Lettow-Vorbeck, were greatly outnumbered. But they still won both battles. The British official history called these events "one of the most notable failures in British military history."

A German warship, the Königsberg, was in the Indian Ocean. It sank a British ship, the Pegasus, in Zanzibar harbor. The Königsberg then hid in the Rufiji River delta. British warships trapped it there. In July 1915, British ships destroyed the Königsberg. The Germans salvaged its guns. These powerful guns were then used by Lettow-Vorbeck's army on land.

Lake Tanganyika Expedition

The Germans controlled Lake Tanganyika at the start of the war. They had three armed ships. In 1915, the British brought two small motorboats, Mimi and Toutou, by land to the lake. These boats were armed with small guns.

On December 26, they captured a German ship, the Kingani. They renamed it Fifi. With two Belgian ships, they attacked and sank another German ship, the Hedwig von Wissmann. This left only one main German ship, the Graf von Götzen. In February 1916, the Germans removed its gun. They sent it to the main fighting front. The ship was later sunk by the Germans themselves. This was to prevent it from being captured by advancing Belgian troops.

Allied Attacks (1916–1917)

British Empire Reinforcements

In 1916, General Jan Smuts was put in charge of defeating Lettow-Vorbeck. Smuts had a very large army. It included about 13,000 soldiers from South Africa, Britain, and Rhodesia. He also had 7,000 troops from India and other African regions. There was also a Belgian force and Portuguese units.

A huge number of African porters (carriers) helped the British. They carried supplies deep into the country. Even with this large force, Smuts's army struggled. Many soldiers got sick from diseases during their long marches.

The Germans, led by Lettow-Vorbeck, usually retreated from larger British forces. By September 1916, the British controlled the main German railway. This cut off German supplies.

As Lettow-Vorbeck was pushed south, Smuts began to send his South African, Rhodesian, and Indian troops home. He replaced them with African soldiers from the King's African Rifles (KAR). By the end of the war, almost all British forces in East Africa were African. Smuts himself left in January 1917.

Belgian Attacks

The British helped the Belgians by providing many carriers. These carriers moved Belgian supplies and equipment. The Belgian army, called the Force Publique, began its campaign on April 18, 1916. They quickly captured Kigali in Rwanda on May 6.

The German Askari in Burundi were forced to retreat. The Belgian forces occupied Burundi and Rwanda by June 17. The Belgians and British then pushed to capture Tabora. This was an important German administrative base.

At the Battle of Tabora on September 19, the Germans were defeated. The Belgians occupied the town. Many carriers died during these marches, mostly from disease. To prevent Belgium from claiming German territory after the war, the British ordered them to return to the Congo. They were only allowed to occupy Rwanda and Burundi.

British Offensive in 1917

Major-General Arthur Hoskins took command of the British forces. After reorganizing supplies, he was replaced by Major-General Jacob van Deventer. Deventer launched a new attack in July 1917. By autumn, the Germans were pushed 100 miles south.

From October 15–19, 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck fought a costly battle at Mahiwa. The Germans had 519 casualties, but the British lost 2,700 men. After this battle, Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to Major General.

German Attacks (1917–1918)

Into Portuguese Mozambique

British forces pushed the German Schutztruppe further south. On November 23, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed into Portuguese Mozambique. He planned to take supplies from Portuguese army bases.

Lettow-Vorbeck divided his force. One group of 1,000 men ran out of food and ammunition. They were forced to surrender before reaching Mozambique. Lettow-Vorbeck and his main force marched through Mozambique for nine months. They won several important battles, like the Battle of Ngomano. This allowed them to keep fighting. But they also came close to being destroyed in battles like Lioma.

Into Northern Rhodesia

The Germans returned to German East Africa. In August 1918, they crossed into Rhodesia. By early October, news of Germany losing the war began to spread. This caused German morale to drop. More and more African carriers deserted.

On November 9, the German force reached Kasama. The British officer there had already left the town. He took all the ammunition with him. The Germans pursued him. On November 12, the Germans attacked a rubber factory where the British had stored supplies. They captured the factory after a four-hour fight.

A British messenger was captured. He told the Germans about the armistice (the end of the war). This news stopped another attack on the factory. Lettow-Vorbeck met the British officer. He found it hard to believe that Germany had lost the war.

German Surrender

The news of Germany's defeat was a big shock to the Germans. At 11:00 a.m. on November 25, 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered to the British. This happened at Abercorn, two weeks after the armistice in Europe.

The governor of German East Africa, Heinrich Schnee, did not sign the surrender. This was to show that Germans still claimed the colony. The British insisted on an unconditional surrender. Lettow-Vorbeck protested but eventually agreed. The campaign was very expensive for the British.

Aftermath

Impact on Society and Economy

The war in East Africa led to a boom in exports for British East Africa. It also increased the power of white colonists in Kenya. The Kenyan economy grew. Exports like cotton and tea increased greatly. White control over the economy also rose significantly.

The war and the recruitment of soldiers also led to the Chilembwe rebellion in January 1915. This was led by John Chilembwe, an African Baptist minister. He was upset about forced labor and unfair treatment by the colonial system. The rebellion failed, but it is seen as a very important event in the history of Malawi.

Casualties and Human Cost

The East African campaign caused many deaths.

- About 11,189 British soldiers died.

- Around 95,000 African porters (carriers) died.

- Belgian forces lost 2,620 soldiers and 15,650 porters.

- Portuguese forces had 5,533 soldiers killed.

- German forces had over 16,000 military casualties.

The exact number of African civilians who died is not known. Many were forced to work as carriers. They were often not paid. Food and cattle were taken from villages. This led to food shortages and famine. A famine caused by the war and bad rains in 1917 killed about 300,000 civilians in German East Africa.

The war also led to the spread of the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918. This flu killed many people in Africa. In Kenya and Uganda, 160,000–200,000 people died. In German East Africa, 10–20 percent of the population died from famine and disease. Overall, the war in East Africa led to the deaths of at least 350,000 civilians. Many German officers, including Lettow-Vorbeck, never showed regret for these losses.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |