Chilembwe uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chilembwe Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of African theatre of World War I | |||||||

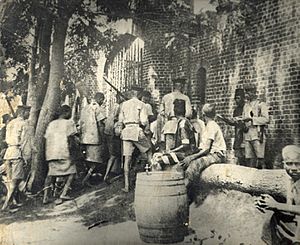

Chilembwe supporters being led to be executed. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Chilembwe Rebels Supported by: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

John Chilembwe † David Kaduya |

||||||

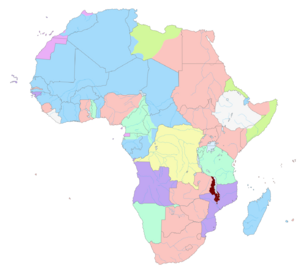

The Chilembwe uprising was a brave fight against British colonial rule in Nyasaland. This country is known today as Malawi. The uprising happened in January 1915. It was led by John Chilembwe, a Baptist minister who studied in America.

The rebellion started from his church in Mbombwe village. The leaders were mostly educated black people. They were upset about many things under colonial rule. These included forced labor, unfair treatment because of their race, and new rules after World War I began.

The revolt began on January 23, 1915. Rebels, encouraged by Chilembwe, attacked a large farm called the A. L. Bruce Plantation. They killed three white people there. Later that night, they tried to get weapons from a store in Blantyre, but this attack was not very successful.

By January 24, the British authorities had gathered their local soldiers and police. They also brought in regular army units called the King's African Rifles (KAR). Government troops attacked Mbombwe on January 25, but they failed to capture it. The rebels then attacked a Christian mission at Nguludi and burned it down.

The KAR and local soldiers took Mbombwe without a fight on January 26. Many rebels, including Chilembwe, ran away towards Portuguese Mozambique (modern Mozambique). They hoped to find safety there. However, many were caught. About 40 rebels were executed, and 300 were put in prison. Chilembwe himself was shot and killed by police on February 3 near the border.

Even though the rebellion did not succeed right away, it is a very important event in Malawian history. It changed how the British ruled Nyasaland, and some improvements were made. After World War II, people in Malawi who wanted independence remembered the Chilembwe revolt. After Malawi became independent in 1964, the uprising became a celebrated moment. John Chilembwe is still seen as a national hero today. His memory is often used by Malawian leaders in their speeches and symbols. The uprising is celebrated every year.

Contents

Why Did the Chilembwe Uprising Happen?

British rule in the area of modern-day Malawi began around 1899-1900. The British wanted to control the land to stop other European countries like Germany or Portugal from taking it. The area became a British protectorate in 1891, called "British Central Africa." In 1907, it was renamed Nyasaland.

Unlike some other parts of Africa, the British controlled Nyasaland mainly because they had a stronger army. In the 1890s, the British put down many rebellions by local groups like the Yao, Ngoni, and Cewa peoples.

British rule completely changed the way local power worked. White settlers came and bought large areas of land from local chiefs. They often paid very little, like beads or guns. Most of this land, especially in the Shire Highlands, became large farms called plantations. Here, they grew crops like tea, coffee, cotton, and tobacco.

The British also introduced new rules, like the Hut Tax. This tax made many local people need to find paid work. The farms needed many workers, so they became major employers. But black workers on these farms were often beaten and treated unfairly because of their race. The farms also used a system called thangata. This system forced people to work for the farm owner to pay their rent. It was a form of forced labor.

John Chilembwe and His Church Mission

John Chilembwe was born around 1871 in the local area. He first went to a Church of Scotland mission school. Later, he met Joseph Booth, a Baptist missionary. Booth believed that all people should be equal, and Chilembwe liked this idea.

Booth helped Chilembwe travel to the United States. There, Chilembwe studied at a religious college in Virginia. He spent time with African-American communities. He was inspired by stories of John Brown, who fought against slavery, and Booker T. Washington, who promoted education and self-help for black people.

Booth was critical of the colonial government and the rich lifestyle of some Protestant churches in Nyasaland. He believed Africans should manage their own businesses and economy. He wanted to "restore Africa to the African." Booth's ideas deeply influenced Chilembwe.

Chilembwe returned to Nyasaland in 1900. With help from an American Baptist group, he started his own independent church. It was called the Providence Industrial Mission in Mbombwe village. At first, the British saw him as someone who promoted peaceful progress for Africans.

He opened many independent black African schools, teaching over 900 students. He also started a group called the Natives' Industrial Union. This group helped African businesses work together. However, Chilembwe's activities caused problems with the managers of the local Alexander Livingstone Bruce Plantation. They worried about Chilembwe's influence over their workers. In November 1913, workers from the Bruce Estates burned down churches built by Chilembwe or his followers on the estate's land.

Chilembwe's ideas became very popular, and he gained many followers. For many years, he taught that Africans should respect themselves and improve through education and hard work. He encouraged his followers to dress and act like Europeans. Many of his main followers were from the local middle class. They had also adopted European customs. Chilembwe's acceptance of European culture led to a unique anti-colonial idea. It was about African self-rule, not just going back to old ways.

Chilembwe also started his own farm, growing coffee, rubber, and cotton. He earned respect from both Africans and Europeans until 1914. He became a leader for African farmers and business owners. He understood the problems faced by both poor African workers and new African business owners. Both groups hated the thangata system. This system forced tenants to work for the estate owner to pay rent and "hut tax." This labor was often demanded during the rainy season, when Africans needed to work on their own farms.

African farmers also faced unfair rules. They could not own land or get loans. They were also treated badly by white landowners and even some Christian ministers. White settlers often used harsh words towards educated Africans. This unfair treatment was a major reason for the rebellion.

After 1912, Chilembwe's ideas became more radical. He began to talk about the liberation of Africans and the end of colonial rule. He connected with other independent African churches. From 1914, he preached more forceful sermons. He often used stories from the Old Testament, like the Israelites' escape from slavery in Egypt. Some of his followers were influenced by the Watch Tower movement, which believed the world would end soon.

World War I and Its Impact

World War I started in July 1914. By September 1914, the war had reached Africa. The British and Belgians began a long fight against the German army in German East Africa. In Nyasaland, the war meant that many Africans were forced to become porters. Porters carried supplies for the Allied armies. They lived in terrible conditions and many died from disease.

At the same time, taking so many porters caused a shortage of workers. This made life even harder for Africans in Nyasaland. Some people believed World War I was a sign of the end of the world. They thought it would destroy the colonial powers and lead to independent African nations.

Chilembwe did not want the people of Nyasaland to fight in a war that he felt had nothing to do with them. He believed in Christian pacifism, which means not fighting. He argued that since Africans had no civil rights under colonial rule, they should not have to serve in the military.

Planning the Uprising

Plans for the uprising began by the end of 1914. It's not fully clear what Chilembwe wanted to achieve. Some people thought he wanted to become "King of Nyasaland." He got a military textbook and started organizing his followers. He also made strong connections with Filipo Chinyama, who lived about 110 miles north-west. Chinyama promised to help the rebellion when it started.

The colonial authorities received two warnings about the revolt. A former follower of Chilembwe told a British official about Chilembwe's plans in August 1914. A Catholic mission was also warned. But no one took any action. This was because the colonial government could not confirm the rumors, as the uprising was planned very secretly.

The Rebellion Begins

The Start of the Revolt

"This is the only way to show the whitemen, [sic] that the treatment they are treating our men and women was most bad and we have determined to strike a first and a last blow and then we will all die by the heavy storm of the whiteman's army. The whitemen will then think, after we are dead, that the treatment they are treating [sic] our people is bad, and they might change to the better for our people."

On the night of Saturday, January 23–24, the rebels met at Chilembwe's church in Mbombwe. Chilembwe gave a speech. He told them that they should not expect to survive the British response. But he said the uprising would make people pay attention to their unfair conditions. He believed this was the only way to bring about change.

A group of rebels went to Blantyre and Limbe, about 15 miles south. Most white colonists lived there. The rebels hoped to capture weapons from the African Lakes Company's store. Another group headed to the Alexander Livingstone Bruce Plantation's main office at Magomero. Chilembwe sent a message to Chinyama in Ncheu to tell him the rebellion was starting.

Chilembwe also tried to get help from German forces in German East Africa. He hoped that a German attack from the north, combined with his rebellion in the south, would force the British out of Nyasaland. On January 24, he sent a letter to the German Governor. But the messenger was caught, and the letter never arrived.

Attack on the Bruce Plantation

The main event of the Chilembwe uprising was the attack on the Bruce plantation at Magomero. This farm was about 5,000 acres and grew cotton and tobacco. Around 5,000 local people worked there because of their thangata duties. The plantation was known for treating its workers badly and for its cruel managers. They closed local schools, beat workers, and paid them less than promised. The burning of Chilembwe's church in November 1913 made the rebel leaders especially angry.

The rebels launched two attacks at the same time. One group went to Magomero, where the main manager, William Jervis Livingstone, and other white staff lived. A second group attacked Mwanje, a village owned by the plantation, where two white families lived.

The rebels entered Magomero in the early evening. Livingstone and his wife were having dinner guests. Another official, Duncan MacCormick, was in a nearby house. A third building held Emily Stanton, Alyce Roach, five children, and a small amount of weapons.

The rebels quietly broke into Livingstone's house. They hurt him during a struggle. He went to his bedroom, where his wife tried to help his wounds. The rebels forced their way in, captured his wife, and then cut off Livingstone's head. MacCormick, who had been alerted, was killed by a rebel spear. The attackers took the women and children prisoner but soon released them unharmed. They reportedly treated them well. It is thought that Chilembwe might have wanted to use them as hostages. The attack on Magomero, especially killing Livingstone, was very important to Chilembwe's men. The two Mauser rifles taken from the plantation became the rebels' main weapons for the rest of the uprising.

Mwanje had little military value. But the rebels might have hoped to find weapons there. Led by Jonathan Chigwinya, the rebels stormed one house. They killed Robert Ferguson, the plantation's stock manager, with a spear as he lay in bed. Two colonists, John Robertson and his wife Charlotte, escaped into the cotton fields. They walked 6 miles to a nearby farm to warn others. One of the Robertsons' African servants, who stayed loyal, was killed by the attackers.

Later Actions of the Rebels

The rebels cut the telephone lines, which slowed down the news. About 100 rebels raided the African Lakes' Company weapons store in Blantyre around 2:00 AM on January 24. This was before the news of the Magomero and Mwanje attacks had spread. The defenders fought back after an African watchman was shot dead by the rebels. The rebels were pushed back, but they did get five rifles and some ammunition. These were taken back to Mbombwe. Some rebels were captured during the retreat from Magomero.

After the first attacks on the Bruce plantation, the rebels went home. Livingstone's head was taken back and shown at the Providence Industrial Mission. This happened on the second day of the uprising, as Chilembwe gave a sermon. During much of the rebellion, Chilembwe stayed in Mbombwe praying. The rebel leadership was taken over by David Kaduya, a former soldier in the King's African Rifles (KAR). Under Kaduya's command, the rebels ambushed a small group of government soldiers near Mbombwe on January 24. This was the only time the government suffered a defeat during the uprising.

By the morning of January 24, the government had gathered its local volunteer soldiers. They also moved the 1st Battalion, KAR, from the north of the colony. The rebels did not attack any other farms in the area. They also did not take over the boma (fort) at Chiradzulu, which was only 5 miles from Mbombwe and had no soldiers. Rumors of rebel attacks spread. But despite earlier promises of help, no other uprisings happened in Nyasaland. The promised help from Ncheu did not arrive. The Mlanje or Zomba regions also refused to join the uprising.

The End of the Rebellion

KAR troops launched an attack on Mbombwe on January 25. But the fight was not decisive. Chilembwe's forces held a strong defensive position along the Mbombwe river. They could not be pushed back. Two African government soldiers were killed, and three were wounded. Chilembwe's side lost about 20 people.

On January 26, a group of rebels attacked a Catholic mission at Nguludi. It belonged to Father Swelsen. The mission was defended by four armed African guards. One guard was killed. Father Swelsen was also wounded, and the church was burned down. A young girl inside died. The military and local soldiers attacked Mbombwe again the same day. But they found no resistance. Many rebels, including Chilembwe, had fled the village dressed as regular people.

Mbombwe's fall and the government troops destroying Chilembwe's church with dynamite ended the rebellion. Kaduya was captured and taken back to Magomero. He was publicly executed there. This was the last attack of the rebellion.

After the defeat, Chilembwe went to Chilimankhanje hill to think. He was later convinced to escape to Mozambique, a place he knew from hunting trips. Chilembwe also wrote a letter to the German colonial government asking for help. He never got a reply.

Most of the remaining rebels tried to escape east towards Portuguese East Africa. They hoped to go north to German territory from there. Chilembwe was seen by a police patrol and shot dead on February 3 near Mlanje. Many other rebels were captured. 300 were put in prison, and 40 were executed. About 30 rebels escaped capture and settled in Portuguese territory near the Nyasaland border.

What Happened After the Uprising?

The British authorities quickly responded to the uprising. They used many soldiers, police, and volunteers to find and kill suspected rebels. There is no official number, but perhaps 50 of Chilembwe's followers were killed in fighting, while escaping, or were quickly executed. The authorities were worried the rebellion might start again. They punished the local African population harshly. This included burning many huts. All weapons were taken away. Fines of 4 shillings per person were charged in the areas affected by the revolt, even if people were not involved.

A series of quick trials were held. Forty-six men were sentenced to death for murder and treason. 300 others were sent to prison. Thirty-six were executed. To scare others, some of the leaders were hanged in public on a main road near the Magomero Estate, where Europeans had been killed.

The colonial government also started to limit the rights of missionaries in Nyasaland. They banned many smaller churches, especially those from America, like the Churches of Christ and Watchtower Society. They also put limits on other African-run churches. Public gatherings, especially religious ones, were banned until 1919. Fear of similar uprisings in other colonies led to similar actions against independent churches there.

Even though the rebellion failed, it forced the British to make some changes. The colonial government wanted to reduce the power of independent churches like Chilembwe's. They tried to promote secular education, but they didn't have enough money. The government also started to promote loyalty to different tribes. This was done through a system called indirect rule, which was expanded after the revolt. The Muslim Yao people, who tried to stay away from Chilembwe, were given more power. The Nyasaland Police, which was mostly African soldiers led by white officials, was changed into a professional force of white colonists. Forced labor continued, and it remained a source of anger for many years.

While many ordinary Yao people felt sympathy for the uprising, none of the Yao chiefs in the Shire Highlands supported it. Most of them were Muslim and saw the African farmers as a threat to their power. A special investigation committee said the uprising was a local problem caused by bad treatment on the Magomero estate. However, the problems Chilembwe spoke about were common across Nyasaland. Africans had no rights as tenants under the thangata system. They had to pay rent with labor and were not allowed to gather wood or hunt animals on land around European farms. Many Africans saw the thangata system as a new form of slavery.

The rebels came from different backgrounds, including Yao people, Lomwe immigrants, farmers, and African business owners. The colonial government ignored African requests and did not translate their laws into local languages. This meant many locals did not understand the laws. Historians note that Africans in Nyasaland were increasingly angry about the physical abuse and mistreatment they faced. If the rebellion had gotten support from German East Africa and captured more weapons, it could have become a much bigger fight. The rebellion was a response to colonial oppression, especially racial injustice. It was a "struggle for freedom" with ideas of Christian hope.

The Commission of Enquiry

After the revolt, the colonial government formed a Commission of Enquiry. This group was to investigate why the rebellion happened and how it was handled. The Commission finished its report in early 1916. It found that the main cause of the revolt was the bad management of the Bruce plantation. The Commission also blamed Livingstone himself for treating local people "often unduly harsh." It also said he managed the estate poorly. The Commission found that unfair treatment and a lack of freedom and respect were key reasons for the anger among the local people. It also highlighted the effect of Booth's ideas on Chilembwe.

The Commission's changes were not very big. Even though it criticized the thangata system, it only made small changes to stop "casual brutality." The government passed laws in 1917 to stop plantation owners from using their tenants' services as rent. This was supposed to end thangata, but it was "uniformly ignored." Another Commission in 1920 said that thangata could not be truly ended. It remained a problem until the 1950s.

Chilembwe's Legacy in Malawi

Even though it failed, the Chilembwe rebellion has become very important in modern Malawian culture. Chilembwe himself is seen as a hero. The uprising was well-known locally in the years after it happened. Former rebels were watched by the police. Over the next thirty years, people who fought against colonial rule saw Chilembwe as a legendary figure.

The Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) in the 1940s and 1950s used him as a symbol. This was partly because its president, James Chinyama, was related to Filipo Chinyama, who was thought to be Chilembwe's ally. When the NAC said it would celebrate Chilembwe Day every year on February 15, colonial officials were shocked. One wrote that honoring "the fanatic and blood thirsty Chilembwe seems to us to be nothing less than a confession of violent intention."

D. D. Phiri, a Malawian historian, said Chilembwe's uprising was an early sign of Malawian nationalism. George Shepperson and Thomas Price also wrote about this in their 1958 book Independent African. This book was a detailed study of Chilembwe and his rebellion. It was banned during colonial times but was still widely read by educated people. Many people in Malawi began to see Chilembwe as a clear hero.

The Malawi Congress Party (MCP) led the country to independence in 1964. They made a clear effort to connect their leader, Hastings Banda, with Chilembwe. They did this through speeches and radio broadcasts. Bakili Muluzi, who became president after Banda in 1994, also used Chilembwe's memory to gain support. He started a new national holiday, Chilembwe Day, on January 16, 1995. Chilembwe's picture was soon put on the national money, the kwacha, and on Malawian stamps. It has been said that for Malawian politicians, Chilembwe has become a "symbol, legitimising myth, instrument and propaganda."

See also

- Bussa rebellion—a 1915 uprising against British rule in northern Nigeria

- Chimurenga—a rebellion against the British South Africa Company administration in nearby Southern Rhodesia in 1896–97.

- Maji Maji Rebellion—a war against German colonial rule in East Africa, 1905–08

- History of Malawi

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |