Nyasaland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nyasaland Protectorate

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1907–1964 | |||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | British protectorate | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Lilongwe | ||||||||||||

| Languages |

|

||||||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

|

• 1907–1910

|

Edward VII | ||||||||||||

|

• 1910–1936

|

George V | ||||||||||||

|

• 1936

|

Edward VIII | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

|

• 1907–1908

|

Sir William Manning | ||||||||||||

|

• 1961–1964

|

Sir Glyn Smallwood Jones | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative council | ||||||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||||||

|

• Establishment

|

6 July 1907 | ||||||||||||

|

• Federation

|

1 August 1953 | ||||||||||||

|

• Dissolution

|

31 December 1963 | ||||||||||||

| 6 July 1964 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

|

• Total

|

102,564 km2 (39,600 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

|

• 1924 census

|

6,930,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Malawi | ||||||||||||

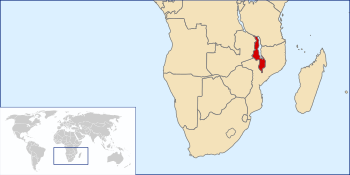

Nyasaland was a British protectorate in Africa. It was created in 1907 when the British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. From 1953 to 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After this group broke up, Nyasaland became independent from Britain on July 6, 1964. It was then renamed Malawi.

Nyasaland's history included a big problem with African communities losing their land early on. In January 1915, a reverend named John Chilembwe led a small uprising. This was to protest unfair treatment against Africans. After this, British leaders looked at some of their rules again.

From the 1930s, more educated Africans became active in politics. Many had studied in the United Kingdom. They wanted independence. They formed groups, and in 1944, they created the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC).

In 1953, Nyasaland was forced to join a Federation with Southern and Northern Rhodesia. This was very unpopular and caused unrest. The NAC failed to stop this, which led to its decline. But soon, younger, more determined members brought the NAC back to life. They asked Hastings Banda to come back and lead the country to independence. This happened in 1964, when Nyasaland became Malawi.

People of Nyasaland

The first census after Nyasaland was renamed was in 1911. It showed about 969,183 Africans, 766 Europeans, and 481 Asians. By 1920, there were 1,015 Europeans and 515 Asians. The number of Africans was estimated at 1,226,000. Blantyre, the main town, had about 300 European residents.

The number of Europeans living there was always small. It was only 1,948 in 1945. By 1960, it grew to about 9,500. But it dropped after the fight for independence began. The number of Asian residents, many of whom were traders, was also small.

Africans in Nyasaland did not have full British citizenship. They had a lesser status called "British protected person." This term was used in all official counts until 1945.

The population grew quite fast. It doubled between 1901 and 1931. However, many babies died, and tropical diseases were common. This meant the population only grew by 1% to 2% each year naturally. The rest of the growth came from people moving in, mostly from Mozambique.

From 1931 to 1945, natural population growth doubled. This was likely due to better medical care. People continued to move in, but it became less important for population growth.

Many people from Mozambique, called "Anguru" (Lomwe-speaking), moved into Nyasaland. In 1921, over 108,000 Anguru were counted. Their numbers grew by more than 60% between 1931 and 1945. By 1966, about 70% of foreign-born Africans in Malawi were from Mozambique.

At the same time, many men left Nyasaland to work in other countries. They went mainly to Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. This loss of workers likely slowed down Nyasaland's development. In 1935, about 58,000 adult men were working outside Nyasaland. By 1937, this number was over 90,000. Many of these workers lost touch with their families.

By 1945, almost 124,000 adult men and 9,500 adult women were working abroad. Most of these migrant workers came from the northern and central parts of the country. This trend continued even after independence. In 1963, about 170,000 men were working abroad.

How Nyasaland Was Governed

From 1907 to 1953, the British government directly controlled Nyasaland. A Governor, chosen by Britain, led the administration. The Governor reported to the Colonial Office in London. Nyasaland also needed money from Britain, so Governors reported to the Treasury on money matters.

From 1953 to 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. This Federation was not fully independent. It was still under the British government. Nyasaland remained a protectorate. Its Governors still managed local affairs, education for Africans, farming, and policing.

Most of the Governor's powers went to the Federal government. This government handled foreign affairs, defense, and higher education. The Colonial Office kept control over African affairs and land ownership. The Federation officially ended on December 31, 1963. Nyasaland became independent on July 6, 1964.

Governors were helped by heads of departments. These officials also served on two councils that advised the Governors. The Legislative Council was set up in 1907. It advised on laws. From 1909, some non-official members were added. The Governor could stop any law passed by this council until 1961. The Executive Council was a smaller group that advised on policy.

The Legislative Council slowly became more representative. In 1930, white planters and business owners chose their six non-official members. Until 1949, only one white missionary represented African interests. That year, the Governor appointed three Africans and one Asian to the council.

From 1955, the six white non-official members were elected. Five Africans were nominated, but no Asians. In 1961, all Legislative Council seats were filled by election. The Malawi Congress Party won 22 out of 28 seats. This party also got seven of the 10 Executive Council seats.

Local Government

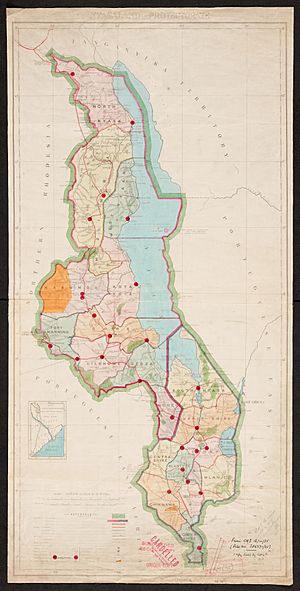

The protectorate was divided into districts starting in 1892. A Collector of Revenue, later called a District Commissioner, was in charge of each. There were about a dozen districts at first, growing to about two dozen by independence. These officials collected taxes and had judicial duties as magistrates.

From 1920, District Commissioners reported to three Provincial Commissioners. These were for the Northern, Central, and Southern provinces. They, in turn, reported to the Chief Secretary in Zomba. The number of District Commissioners slowly grew to 120 by 1961.

In many areas, there were not many strong traditional chiefs. At first, the British tried to reduce the chiefs' power. They preferred direct rule by the Collectors. From 1912, Collectors could appoint headmen. These headmen acted as links between the British and local people. This was an early form of Indirect rule.

In 1933, another form of indirect rule began. The government recognized chiefs and their councils as Native Authorities. But they had little real power or money. Native Authorities could set up Native Courts. These courts decided cases using local customary law. However, they were watched over by District Commissioners. They were often used to enforce unpopular farming rules. Still, they handled most civil disputes.

From 1902, English law became the official legal system. A High Court was set up like in England. Appeals went to the East African Appeals Court in Zanzibar. Customary law could be used in cases involving Africans. But only if it did not go against English legal principles.

Order was first kept by soldiers from the King's African Rifles. Some helped the District Commissioners. Others were poorly trained police. A better police force was set up in 1922. But in 1945, it still had only 500 constables.

After World War II, the government spent more on police. They expanded forces into rural areas. A Police Training School opened in 1952. Police numbers grew to 750 by 1959. New units were created for riot control. But these changes were not enough during major unrest in 1959. The government declared a state of emergency. Military forces came from Rhodesia and Tanganyika. Police numbers quickly grew to about 3,000.

Land Ownership Issues

European ownership of large areas of land caused a big problem. Africans increasingly felt their land was being taken. Between 1892 and 1894, Europeans gained control of about 3.7 million acres. This was about 15% of the protectorate's total land. Most of this was in the north and was not used for farming.

But much of the remaining land, about 867,000 acres, was in the Shire Highlands. This was the most crowded part of the country. It had the best farming land. Africans there relied on growing their own food. The first British Commissioner, Sir Harry Johnston, hoped Europeans would settle there. But he later realized it was unhealthy and had many Africans who needed the land.

Later, around 250,000 acres of Crown Lands were sold or leased. Another 400,000 acres were sold or leased in smaller farms. Many of these were for Europeans who came after World War I to grow tobacco. In 1920, a Land Commission suggested selling even more land to Europeans. But the Colonial Office rejected this idea.

Much of the best land in the Shire Highlands was given to Europeans. Two large areas, from Zomba to Blantyre-Limbe and from Limbe to Thyolo, became almost entirely European estates. In these areas, land for Africans was rare and very crowded.

In the early years, little of the estate land was farmed. Settlers wanted workers. They encouraged Africans already living there to stay. New workers, often migrants from Mozambique, were also encouraged to move onto estates. They grew their own crops but had to pay rent. At first, this was usually two months of work each year. This system was called thangata. Later, owners often demanded more work.

In 1911, about 9% of Africans lived on estates. By 1945, it was about 10%. These estates made up 5% of the country's area. But they had about 15% of the best farming land.

Three big estate companies owned land in the Shire Highlands. The British Central Africa Company once owned 350,000 acres. A L Bruce Estates Ltd owned 160,000 acres. Blantyre and East Africa Ltd owned 157,000 acres. These companies later started charging cash rents from their African tenants.

The 1920 Land Commission looked at the situation of Africans on private estates. It suggested giving tenants more secure rights to their land. Rents would be regulated. These ideas became law in 1928. Before 1928, the rent was usually 6 shillings (30 pence) a year. After 1928, the maximum cash rent was £1 for an 8-acre plot. Estate owners could remove up to 10% of their tenants every five years. They could also refuse to let male children of residents stay after age 16. This was to prevent overcrowding. But there was little land for those who were forced to leave. From 1943, people started to resist these evictions.

Land for Africans

British law in 1902 said that all land not already given to Europeans was Crown Land. This land could be sold without asking the residents. In 1904, the Governor gained power to set aside Crown Land for African communities. This was called Native Trust Land. It was not until 1936 that converting Native Trust Land to private ownership was stopped. This law aimed to make Africans feel safer about their land rights.

Most people in Nyasaland lived in rural areas. Over 90% of rural Africans lived on Crown Lands (including the reserves). Their access to land for farming was based on traditional laws. These laws usually gave a person the right to use land for farming for a long time. They could pass it to their children. Community leaders were expected to give land to community members. But they would limit land for outsiders.

It has been said that Malawi had enough farming land for its people. This would be true if the land was shared equally and used for food. However, as early as 1920, some areas were already crowded. Families had only 1 to 2 acres to farm. By 1946, these crowded areas were even worse.

Land Changes

From 1938, the government started buying small amounts of unused estate land. This was for people who had been evicted. But these purchases were not enough. In 1942, hundreds of Africans in Blantyre District refused to leave their homes. They had no other land to go to. Two years later, the same problem happened in Cholo District. Two-thirds of its land was private estates.

In 1946, the Nyasaland government set up a commission. It was called the Abrahams Commission. It looked into land problems after riots by tenants on European estates. Sir Sidney Abrahams, the only member, suggested that the government buy all unused private land. This land would become Crown land for African farmers. Africans on estates could choose to stay as workers or tenants, or move to Crown land. These ideas were not fully put into action until 1952.

The Abrahams report caused different opinions. Africans generally liked the ideas. So did the governors from 1942 to 1956. But estate owners and many European settlers strongly opposed it.

Because of the Abrahams report, the government set up a Land Planning Committee in 1947. This committee advised on buying land for resettlement. It recommended buying only land that was undeveloped or had many African residents. Land that could be developed into estates in the future was to be protected. From 1948, more land was bought. Estate owners became more willing to sell. In 1948, about 1.2 million acres of private estates remained. They had an African population of 200,000. By independence in 1964, only about 422,000 acres of European-owned estates were left. These were mainly tea estates or small farms.

Nyasaland's Economy

Nyasaland had some minerals, like coal. But these were not used much during colonial times. Without valuable minerals, the economy had to rely on farming. In 1907, most people were subsistence farmers. This means they grew food mainly for their families.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, people grew cassava, rice, beans, and millet. They also grew maize, sweet potatoes, sorghum, and groundnuts. These crops remained staple foods. Tobacco and a local type of cotton were also widely grown.

The colonial Department of Agriculture favored European farmers. It did not support African farming enough. This stopped a strong local farming economy from growing. The department criticized "shifting cultivation." This is where trees are cut and burned. Their ashes fertilize the soil. The land is used for a few years, then a new area is cleared. This method works well when there is enough land.

Many soils in Africa are not very fertile. They lack nutrients and are easily eroded. Shifting cultivation with long fallow periods (leaving land unplanted) was good for these soils. But as more land was used, fallow times became shorter. This put pressure on soil fertility. However, recent studies show that most soils in Malawi are good enough for small farmers to grow maize.

In the early 1900s, European estates produced most of the crops for export. But by the 1930s, Africans grew a large part of these crops. They were either small farmers on Crown land or tenants on estates. The first main estate crop was coffee. But competition from Brazil and droughts led to its decline. Farmers then turned to tobacco and cotton.

Tea was first planted for business in 1905. It was grown in the Shire Highlands. Tobacco and tea growing increased after the Shire Highlands Railway opened in 1908. For 56 years, tobacco, tea, and cotton were the main export crops. Tea was the only one that remained an estate crop throughout. The main problems for exports were high transport costs and low quality of produce. Also, European farmers did not want Africans growing cotton or tobacco.

Main Crops for Export

The area of flue-cured tobacco grown by European farmers grew from 4,500 acres in 1911 to 14,200 acres in 1920. This produced 2,500 tons of tobacco. Before 1920, about 5% of the tobacco sold was dark-fired tobacco grown by African farmers. This rose to 14% by 1924. World War I increased tobacco production. But after the war, competition from the United States made it harder for Nyasaland growers.

Much of the tobacco from European estates was low quality. In 1921, only 1,500 tons out of a 3,500-ton crop could be sold. Many smaller European growers went out of business. Their numbers fell from 229 in 1919 to 82 in 1935. European tobacco production continued to drop. In 1924, Europeans produced 86% of Malawi's tobacco. By 1936, it was only 16%. Despite this, tobacco made up 65–80% of exports from 1921 to 1932.

A Native Tobacco Board was formed in 1926. This helped increase the production of fire-cured tobacco. By 1935, 70% of the country's tobacco was grown in the Central Province. The Board had about 30,000 registered growers there. Most were small farmers. The number of growers changed over time. By 1950, there were over 104,500 growers. They planted 132,000 acres and grew 10,000 tons of tobacco. The value of tobacco exports kept rising. But its share of total exports dropped after 1935 because tea became more important.

Egyptian cotton was first grown by African small farmers in 1903. It spread to other areas. By 1905, American Upland cotton was grown on estates. African-grown cotton was bought by companies until 1912. Then, government cotton markets were set up. These gave a fairer price.

Cotton production peaked in 1917, reaching 1,750 tons. This was because World War I increased demand. But a lack of workers and floods caused production to drop in 1918. The industry recovered by 1924. It reached 2,700 tons in 1932 and a record 4,000 tons in 1935. This was mainly African production. The importance of cotton exports dropped from 16% in 1922 to 5% in 1932. It then rose to 10% in 1941. By independence, cotton was the fourth most valuable export crop.

Tea was first exported from Nyasaland in 1904. Tea plantations were set up in areas with high rainfall. Exports steadily increased. The importance of tea grew a lot after 1934. It went from 6% of exports in 1932 to over 20% in 1935. It never fell below that level. In some years, tea exports were even more valuable than tobacco. Nyasaland had the largest area of tea farms in Africa until the mid-1960s. However, the main problem was its low quality on the international market.

Groundnut exports were small before 1951. But a government plan to promote them led to a rapid increase. By independence, annual exports were 25,000 tons. Groundnuts became Nyasaland's third most valuable export. They are also widely grown for food. In the 1930s and 1940s, Nyasaland became a major producer of Tung oil. But after 1953, world prices dropped. Tung oil was replaced by cheaper alternatives. Until the 1949 famine, maize was not exported. But a government plan then promoted it as a cash crop. By independence, local demand meant almost no maize was exported.

Hunger and Famine

Hunger during certain seasons was common before and during early colonial times. Farmers grew just enough food for their families. They had little extra to store or trade. Famines often happened during wars.

One idea is that colonialism led to poverty and hunger. This happened by taking land for cash crops. Or by forcing farmers to grow them. This reduced their ability to grow food. Also, farmers were paid too little for their crops. They were charged rents for land and taxed unfairly. This made it hard for them to buy food. The new market economy also weakened old ways of surviving. These included growing backup crops or getting help from family. This created a group of people who were always hungry.

Nyasaland had local famines in 1918. It also had food shortages at different times between 1920 and 1924. The government did little until the situation was very bad. Relief supplies were expensive and slow to arrive. The government was also slow to give free food to those who could work. However, it did import about 2,000 tons of maize for relief in 1922 and 1923. It also bought grain from less affected areas. Even though these famines were smaller than in 1949, the authorities did not prepare well for future ones.

In November and December 1949, the rains stopped early. Food shortages quickly grew in the Shire Highlands. Government workers, city workers, and some estate tenants received free or cheaper food. Those who struggled most were widows, abandoned wives, the elderly, and very young children. Families did not always help distant relatives. In 1949 and 1950, 25,000 tons of food were imported. But initial deliveries were slow. The official death count was 100 to 200. But the real number may have been higher. There were severe food shortages and hunger in 1949 and 1950.

Transportation in Nyasaland

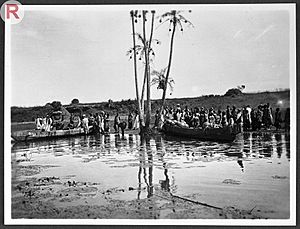

From the time of Livingstone's trip in 1859, the Zambesi, Shire River, and Lake Nyasa waterways were seen as the best way to transport goods. However, the Zambezi-Lower Shire and Upper Shire-Lake Nyasa systems were separated. There were 50 miles (80 km) of waterfalls and rapids in the Middle Shire. This stopped boats from traveling continuously.

The main economic centers in Blantyre and the Shire Highlands were 25 miles (40 km) from the Shire River. Moving goods from the river was slow and costly. People carried goods on their heads or used ox-carts. Until 1914, small river steamers carried goods between Chinde (at the mouth of the Zambezi) and the Lower Shire. This was about 180 miles (290 km). The British government had a 99-year lease for a port at Chinde. Passengers transferred there from ocean ships to river steamers. This service stopped in 1914.

Before the railway opened in 1907, passengers and goods transferred to smaller boats at Chiromo. They went 50 miles (80 km) upstream to Chikwawa. From there, porters carried goods up the hills. Passengers continued on foot. Low water levels in Lake Nyasa made the Shire River flow less from 1896 to 1934. This made navigation difficult in the dry season. The main port moved from Chiromo to Port Herald in 1908. But by 1912, Port Herald was often unusable. So, a Zambezi port was needed. The railway extension to the Zambezi in 1914 ended most water transport on the Lower Shire. Low water ended it on the Upper Shire. But water transport has continued on Lake Nyasa.

Several lake steamers served communities along Lake Nyasa. They were first based at Fort Johnston. Their value increased in 1935. A northern railway extension from Blantyre reached Lake Nyasa. A terminal for Lake Services was built at Salima. However, port facilities at many lake ports were poor. Few good roads led to most ports. Some in the north had no road connection at all.

Railways could help water transport. Nyasaland was over 200 miles (320 km) from a good ocean port. So, a short rail link to river ports was more practical at first. The Shire Highlands Railway opened a line from Blantyre to Chiromo in 1907. It extended to Port Herald in 1908. After Port Herald became difficult to use, the British South Africa Company built the Central African Railway. This 61-mile (98 km) line ran from Port Herald to Chindio on the Zambezi in 1914. From there, goods went by river steamers to Chinde, then by sea to Beira. This involved three transfers and delays.

Chinde was badly damaged by a cyclone in 1922. It was not suitable for larger ships. The other ports were Beira and Quelimane. Beira was busy, but it was improved in the 1920s. The route to Quelimane was shorter, but the port was not well developed. The Trans-Zambezia Railway was built between 1919 and 1922. It ran 167 miles (269 km) from the south bank of the Zambezi. It joined the main line from Beira to Rhodesia.

The Zambezi crossing used ferries with steamers towing barges. This had limited capacity and caused delays. In 1935, a bridge was built over the Zambezi. The Dona Ana Bridge was over 2 miles (3.2 km) long. It created a continuous rail link to the sea. In the same year, a northern extension from Blantyre to Lake Nyasa was finished.

The Zambezi Bridge and northern extension brought less traffic than expected. The rail link was not good for heavy loads. It was a single, narrow-gauge track with sharp curves and steep slopes. Maintenance costs were high, and freight volumes were low. So, transport rates were very high. Despite its problems, the rail link to Beira remained Nyasaland's main transport link. A second rail link to the Mozambique port of Nacala was suggested in 1964. It is now the main route for imports and exports.

Roads in early Nyasaland were just trails. They were barely usable in the wet season. Roads for motor vehicles were developed in the south in the 1920s. They replaced people carrying goods on their heads. But few all-weather roads existed in the north until the late 1930s. So, motor transport was mostly in the south. Road travel was becoming an alternative to rail. But government rules favored railways, which slowed road development. At independence, there were few paved roads.

Air transport started small in 1934. Rhodesian and Nyasaland Airways had a weekly service from Chileka to Salisbury. This increased to twice weekly in 1937. Blantyre (Chileka) was also linked to Beira from 1935. All flights stopped in 1940. But in 1946, Central African Airways restarted services. Its Salisbury to Blantyre service was extended to Nairobi. A Blantyre-Lilongwe-Lusaka service was added. Internal flights ran to Salima and Karonga. The Nyasaland part of the airline became Air Malawi in 1964.

Road to Independence

The first protests against British rule came from two groups. First, independent African churches rejected European control. They promoted ideas that the authorities saw as dangerous. Second, educated Africans wanted social, economic, and political progress. They formed voluntary "Native Associations." Both groups were usually peaceful. But a violent uprising in 1915 by John Chilembwe showed deep frustration. It was also angry about African deaths in World War I.

After Chilembwe's uprising, protests were quiet until the early 1930s. They focused on improving African education and farming. Political representation seemed far away. However, in 1930, the British government said that white settlers north of the Zambezi could not form governments that controlled Africans. This made Africans more aware of politics.

The government of Southern Rhodesia wanted to join with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. A Royal Commission looked into this. Africans were almost all against joining with Southern Rhodesia. The Bledisloe Commission report in 1939 did not completely rule out some form of joining. But it said that Southern Rhodesia's racial discrimination should not be used north of the Zambezi.

The risk of Southern Rhodesian rule made Africans demand political rights more urgently. In 1944, various local groups joined to form the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC). One of its first demands was to have African representatives on the Legislative Council. This was granted in 1949. From 1946, the NAC received help from Hastings Banda, who was living in Britain. Congress lost its drive until new plans for joining the Federation came up in 1948. This gave it new energy.

After the war, British governments thought joining Central African countries would save money. They agreed to a federation, not a full merger. The main African objections were clear. Hastings Banda for Nyasaland and Harry Nkumbula for Northern Rhodesia wrote a joint paper in 1951. They said that white minority rule in Southern Rhodesia would stop Africans from gaining more political power. They also feared more racial discrimination.

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was created in 1953. This happened despite very strong African opposition. There were riots and deaths in Cholo District. In 1953, the NAC opposed the federation and demanded independence. Its supporters protested against taxes and pass laws. In early 1954, Congress stopped its campaign and lost much support. Soon after the Federation was formed, its government tried to take control of African affairs from the British. It also reduced British development plans.

In 1955, the Colonial Office agreed to increase African representation on the Legislative Council. It went from three to five members. African members would no longer be chosen by the governor. Instead, Provincial Councils would nominate them. These councils listened to the people. This allowed them to nominate Congress members to the Legislative Council. This happened in 1956. Henry Chipembere and Kanyama Chiume, two young, strong Congress members, were nominated. This success led to a quick growth in Congress membership in 1956 and 1957.

Some younger members of the Nyasaland African Congress did not trust their leader, T D T Banda. They wanted to replace him with Dr. Hastings Banda. Dr. Banda was living in the Gold Coast. He said he would only return if he became president of Congress. After this was agreed, he returned to Nyasaland in July 1958. T D T Banda was removed from power.

Movement for Independence

Banda and Congress Party leaders started a campaign against the federation. They wanted immediate changes to the government and eventual independence. This included resisting Federal rules on farming. Protests were widespread and sometimes violent. In January 1958, Banda presented Congress's ideas for reform to the governor, Sir Robert Armitage. They wanted Africans to be the majority in the Legislative Council. They also wanted equal power with non-Africans in the Executive Council.

The governor rejected these ideas. This led to demands within Congress for stronger protests and more violent actions. As Congress supporters became more violent, Governor Armitage decided not to make concessions. Instead, he prepared for mass arrests. On February 21, European troops were flown into Nyasaland. In the following days, police or troops shot at rioters in several places. Four people died.

On March 3, 1959, Governor Armitage declared a State of Emergency. This covered the whole protectorate. In an operation called Operation Sunrise, police and military arrested Dr. Hastings Banda. They also arrested other leaders of his party and over a hundred local officials. The Nyasaland African Congress was banned the next day. Those arrested were held without trial. The total number of people held reached over 1,300. Over 2,000 more were jailed for crimes related to the emergency. The government said these actions were to restore order. But instead of calming things, 51 Africans were killed and many more were hurt.

Twenty people were killed at Nkhata Bay. This is where those arrested in the Northern Region were being held. A local Congress leader encouraged a large crowd to gather. They wanted to free the prisoners. Troops arrived late. The District Commissioner felt the situation was out of control and ordered them to shoot. Twelve more deaths happened by March 19. Most were when soldiers shot at rioters. The remaining deaths were in military operations in the Northern Region. The NAC, which was banned, was re-formed as the Malawi Congress Party in 1959.

After the emergency, a commission led by Lord Devlin looked into the problems. The Commission found that declaring a State of Emergency was needed to restore order. But it criticized illegal force used by police and troops. This included burning houses and beatings.

The report concluded that the Nyasaland government had lost the support of its African people. It noted their strong rejection of the Federation. Finally, it suggested that the British government should talk with African leaders about the country's future. The Devlin Commission's report was the only time a British judge examined if a colonial government's actions were right. Devlin's findings that too much force was used and that Nyasaland was a "police state" caused a big stir. His report was mostly rejected. The state of emergency lasted until June 1960.

At first, the British government tried to calm things. They nominated more African members to the Legislative Council. These were not Malawi Congress Party supporters. But soon, they decided the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland could not continue. It officially ended on December 31, 1963. It had already become unimportant to Nyasaland before then. Britain also decided that Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia should have self-government with African majority rule. Banda was released in April 1960. He was invited to London to discuss plans for self-government.

The Malawi Congress Party won a huge victory in the August 1961 elections. Banda and four other party members joined the Executive Council as elected ministers. After a meeting in London in 1962, Nyasaland gained internal self-government. Banda became Prime Minister in February 1963. Full independence came on July 6, 1964. Banda remained Prime Minister. The country became the Republic of Malawi on July 6, 1966, with Banda as president.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nyasalandia para niños

In Spanish: Nyasalandia para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |