History of Malawi facts for kids

The History of Malawi tells the story of the land that is now Malawi. This area was once part of the Maravi Empire in the 1500s, which included parts of modern-day Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia. Later, the British ruled the territory, calling it British Central Africa and then Nyasaland. It also became part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Malawi gained full independence in 1964. After independence, Hastings Banda led Malawi as a one-party state until 1994.

Contents

Ancient Times in Malawi

Scientists found a very old jawbone near Uraha village in 1991. It was about 2.3 to 2.5 million years old! Early humans lived near Lake Malawi a long, long time ago, about 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Human remains from around 8000 BCE look similar to people living today in the Horn of Africa.

At another site, from about 1500 BCE, human remains have features like the San people. These people might have created the rock paintings found south of Lilongwe in Chencherere and Mphunzi. According to Chewa stories, the first people in the area were small archers called Akafula or Akaombwe.

People who spoke Bantu languages arrived in the region between the first and fourth centuries CE. They brought new skills like using iron and slash-and-burn farming. Later groups of Bantu people arrived between the 13th and 15th centuries. They either replaced or mixed with the earlier groups.

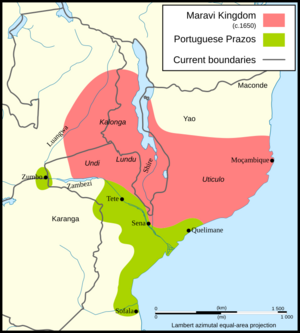

The Maravi Empire

The name Malawi probably comes from the word Maravi. The people of the Maravi Empire were skilled iron workers. "Maravi" might mean "Flames," perhaps from the many kilns lighting up the night sky.

The Maravi Empire was started by the Amaravi people in the late 1400s. The Amaravi later became known as the Chewa. They moved to Malawi from the area of the modern-day Republic of Congo to escape problems and sickness. The Chewa fought against the Akafula, who no longer exist.

The Maravi Empire began on the southwestern shores of Lake Malawi. It eventually covered most of modern Malawi, plus parts of Mozambique and Zambia. The leader of the empire during its growth was called the Kalonga (also spelled Karonga). The Kalonga ruled from his main city, Mankhamba. He appointed sub-chiefs to take over new areas. The empire started to weaken in the early 1700s. This happened because of fighting among the sub-chiefs and the growing slave trade.

Trade and New Groups

Portuguese Traders

At first, the Maravi Empire's economy relied on farming, especially growing millet and sorghum. Europeans first met the people of Malawi during the Maravi Empire, around the 1500s. The Chewa people could reach the coast of modern-day Mozambique. They traded ivory, iron, and people (slaves) with the Portuguese and Arabs. Trade was easier because the Chewa (Nyanja) language was spoken throughout the Maravi Empire.

In 1616, a Portuguese trader named Gaspar Bocarro traveled through what is now Malawi. He wrote the first European description of the country and its people. The Portuguese also brought maize (corn) to the region. Maize eventually became the main food for Malawians. Malawian tribes traded people with the Portuguese. These people were mainly sent to work on Portuguese farms in Mozambique or to Brazil.

The Ngoni People

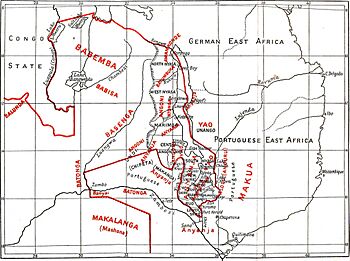

The Maravi Empire declined partly because two strong groups entered the Malawi region. In the 1800s, the Angoni or Ngoni people arrived from the Natal area of South Africa. Their chief was Zwangendaba. The Angoni were part of a big movement of people, called the mfecane. These people were fleeing from Shaka Zulu, the leader of the Zulu Empire.

The Ngoni settled mostly in central Malawi, especially Ntcheu and parts of Dedza district. Some groups went north into Tanzania. Other groups went back south, settling in northern Malawi, like Mzimba district. There, they mixed with another group called the Bawoloka. The Ngoni used Shaka's fighting methods to take over smaller tribes, including the Maravi. They would raid the Chewa, taking food, oxen, and women. Young men joined their fighting forces, while older men became domestic workers or were sold to Arab slave traders.

The Yao People

The second group to become powerful around this time was the Yao. The Yao were richer and more independent than the Makuwa. They came to Malawi from northern Mozambique in the 1800s. They either fled conflict with the Makuwa or wanted to profit from the slave and ivory trades. They traded with Arabs from Zanzibar, the Portuguese, and the French.

When they arrived in Malawi, they soon started buying people from the Chewa and Ngoni. The Yao also attacked these groups to capture people to sell as slaves. When David Livingstone met them, he wrote about their slave trading. The Yao traded far and wide, even with groups in Zimbabwe and the Luangwa river in Zambia.

The Yao were skilled traders and had educated merchants. They built boats for lake travel and set up irrigation for growing rice. Important members of their society started religious schools. The Yao were the first group in Malawi to use firearms, which they bought from Europeans and Arabs. They used these in fights with other tribes.

By the 1860s, the Yao had become Muslims. This conversion likely happened because of their trading trips, especially to the Kilwa Sultanate and Zanzibar. The Yao used Swahili and Arab religious leaders who taught reading and built mosques. Their writings were in Kiswahili, which became a common language in Malawi from 1870 to the 1960s.

Arabs and Swahili Allies

Arab traders, working closely with the Yao, set up trading posts along Lake Malawi. The Yao's journeys to the east taught the Swahili-Arabs about Lake Malawi. A leader named Jumbe (Salim Abdallah) followed the Yao trade route to Nkhotakota. When Jumbe arrived in Nkhotakota in 1840, he found many Yao and Bisa people already living there. Some of these Yao were already Muslims, and he hired them.

At the peak of his power, Jumbe sent between 5,000 and 20,000 people through Nkhotakota each year. From Nkhotakota, these groups of people were taken in large caravans to the island of Kilwa Kisiwani, off the coast of Tanzania. These trading posts shifted the slave trade in Malawi from the Portuguese in Mozambique to the Arabs of Zanzibar.

Even though the Yao and Ngoni often fought, neither side won completely. However, the Ngoni of Dedza decided to work with the Yao of Mpondas. The remaining parts of the Maravi Empire were almost destroyed by attacks from both sides. Some Chewa chiefs saved themselves by making agreements with the Swahili people, who were friends with the Arab slave traders.

The Lomwe People

The Lomwe of Malawi arrived later, around the 1890s. They came from a hill in Mozambique called uLomwe, north of the Zambezi River. They were escaping hunger caused by Portuguese settlers moving into their areas. To escape bad treatment, the Lomwe went north and entered Nyasaland near the southern tip of Lake Chilwa. They settled in the Phalombe and Mulanje areas.

In Mulanje, they found the Yao and Mang'anja people already living there. Yao chiefs welcomed the Lomwe as their relatives from Mozambique. Many Lomwe were given land by the Yao and Mang'anja. Later, the Lomwe found jobs on tea farms that British companies were starting near Mount Mulanje. They gradually spread into Thyolo and Chiradzulu. The Lomwe mixed easily with the local Mang'anja tribes, and there were no reports of tribal conflict.

Early European Visitors

The Portuguese are said to have been the first Europeans to find Malawi. In 1859, following a tip from a Portuguese source, David Livingstone discovered Lake Malawi. The Yao people supposedly told him the large body of water was called Nyasa. Livingstone, who did not know the Chiyao language, might have thought Nyasa was the lake's proper name. However, "Nyasa" in Chiyao simply meant "lake."

On his next journey in 1861, with Bishop Charles Mackenzie from the UMCA, there was conflict. The Muslim Yao were hostile to the non-Muslim Mang'anja, whom the bishop wanted to teach. The Yao who practiced Islam and slavery did not like the Christian missionaries. The fighting stopped after Mackenzie died from malaria.

More missionaries arrived in 1875-76 from the Free Church of Scotland. They set up a base at Cape Maclear at the southern end of Lake Malawi. They also tried to convert the Yao who were Muslims. Some Yao were willing to convert, but progress was slow. Bishop Robert Laws became the leader. Laws became famous for his medical skills. He decided to set up missions further north, at Bandawe among the Tonga and at Kaningina among the Ngoni people.

There, the missionaries found people ready to listen. The missions became safe places for the Tonga, who were often attacked by Ngoni raiders. Some of the Tonga's teachers were Nyanja people who had become Christians at Cape Maclear. In 1878, traders, mostly from Glasgow, formed the African Lakes Company. They supplied goods and services to the missionaries. More people followed: traders, hunters, farmers, and missionaries from other churches. From 1889, the Catholic White Fathers tried to convert the Yao.

In 1894, the mission expanded to the Tumbuka people, who were also being attacked by the powerful Ngoni. Laws opened a mission station near Rumphi that year. The Tumbuka, like the Tonga, sought safety with the missionaries and became Christians. In contrast, the Yao remained mostly separate from Christianity. They continued to write and read in Arabic, which would soon not be recognized in Malawi. This put the Yao at a disadvantage.

The fact that the Yao Muslims did not convert to Christianity led to a negative view of them in older European history books. The Yao's contributions to Malawi's economy and society were not recognized. Instead, history often saw them only as major slave traders. Under H. H. Johnson, the British fought Yao chiefs like Makanjila and Mponda Jalasi for five years before they were defeated. Today, fewer Yao work in jobs requiring literacy. This has led many of them to move to South Africa for work. The Yao believe they have been unfairly treated because of their faith. In Malawi, they mostly work as farmers, tailors, guards, fishermen, or in other manual jobs. At one time, some Yao changed their names to get an education. For example, Mariam became Mary, and Yusufu became Joseph.

British Rule in Nyasaland

In 1883, a British government official was sent to the "Kings and Chiefs of Central Africa." In 1891, the British officially set up the British Central Africa Protectorate.

In 1907, the name changed to Nyasaland or the Nyasaland Protectorate. (Nyasa is the Chiyao word for "lake"). In the 1950s, Nyasaland joined with Northern and Southern Rhodesia in 1953. They formed the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. This Federation ended on December 31, 1963.

In January 1915, John Chilembwe, a Baptist pastor, led a rebellion against British rule. This was called the Chilembwe uprising. Chilembwe did not like that Malawians were forced to be porters in World War I and he opposed the colonial system. Chilembwe's followers attacked local farms. However, government forces quickly defeated the rebels. Chilembwe was killed, and many of his followers were executed.

In 1944, the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) was formed. It was inspired by the African National Congress' Peace Charter. The NAC quickly grew, with strong groups forming among Malawian workers in Salisbury (now Harare) in Southern Rhodesia and Lusaka in Northern Rhodesia.

Thousands of Malawians fought in World War II.

In July 1958, Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda returned to the country after living abroad for a long time. He took over leadership of the NAC, which later became the Malawi Congress Party (MCP). In 1959, Banda was sent to Gwelo Prison for his political actions. But he was released in 1960 to join a meeting in London about the country's future.

In August 1961, the MCP won a huge victory in an election for a new Legislative Council. They also gained an important role in the new Executive Council. A year later, they were basically ruling Nyasaland. In a second meeting in London in November 1962, the British Government agreed to give Nyasaland self-governing status the next year.

Hastings Banda became Prime Minister on February 1, 1963. However, the British still controlled the country's money, security, and legal systems. A new constitution began in May 1963. It gave the country almost complete self-rule.

Malawi Becomes Independent

Quick facts for kids Malawi Independence Act 1964 |

|

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act to make provision for and in connection with the attainment by Nyasaland of fully responsible status within the Commonwealth. |

| Citation | 1964 c. 46 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 10 June 1964 |

|

Status: Amended

|

|

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Text of the Malawi Independence Act 1964 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk | |

Malawi became a fully independent member of the Commonwealth on July 6, 1964.

Soon after, in August and September 1964, Banda faced disagreement from most of his government ministers. This was called the Cabinet Crisis of 1964. The ministers were unhappy with Banda's leadership style. They felt he did not ask for their opinions and kept too much power for himself. They also disagreed with his decisions about relations with South Africa and Portugal, and some money-saving plans.

Three ministers were fired on September 7. Three more resigned in support of them. After more problems and some clashes, most of the former ministers left Malawi in October. One ex-minister, Henry Chipembere, led a small uprising in February 1965, but it failed. Another, Yatuta Chisiza, organized an even smaller attack in 1967, where he was killed. Some of these former ministers died in exile or in jail. But some lived to return to Malawi after Banda was removed from power in 1993.

Two years later, Malawi adopted a new constitution. It became a one-party state with Hastings Banda as its first president.

One-Party Rule in Malawi

In 1970, Hastings Banda was declared President for life of the MCP. In 1971, Banda became president for life of Malawi itself. The Young Pioneers, a group connected to the Malawi Congress Party, helped Banda keep strong control over Malawi until the 1990s.

Banda was a very powerful leader. He was always called "His Excellency the Life President Ngwazi Dr. H. Kamuzu Banda." Everyone had to show loyalty to him. Every business building had to have an official picture of Banda on the wall. No other picture could be placed higher than his. The national anthem played before most events, like movies and school assemblies. At cinemas, a video of him waving to people was shown during the anthem.

When Banda visited a city, a group of women was expected to greet him at the airport and dance for him. They had to wear a special cloth with his picture on it. The country's only radio station played his speeches and government messages. People were sometimes told by police to go inside their homes and lock all windows and doors an hour before President Banda passed by. Everyone was expected to wave.

Banda had strict laws. For women, it was illegal to wear see-through clothes, pants, or skirts that showed any part of the knee. There were exceptions for certain private clubs or hotels. Men were not allowed to have hair below their collar. If men with long hair arrived from other countries, they had to get a haircut at the airport.

Churches had to be approved by the government. Members of some religious groups, like Jehovah's Witnesses, faced difficulties and were sometimes forced to leave the country. All Malawian citizens of Indian heritage were forced to move to special Indian areas in bigger cities. At one point, they were all told to leave the country, then some were allowed to return. It was illegal to send money earned privately out of the country without special permission.

The Malawi Censorship Board watched all movies shown in theaters. They edited out anything they thought was not suitable, especially political content. Mail was also checked. Some mail from other countries was opened, read, and sometimes edited. Videotapes had to be sent to the Board for review. Once edited, a sticker was put on the movie saying it was okay to watch. Phone calls were listened to and cut off if the conversation was critical of the government. Books and magazines were also edited. Pages or parts of pages were cut out or blacked out of magazines like Newsweek and Time.

Dr. Banda was a very rich man. He owned houses, businesses, helicopters, and cars. Speaking against the President was strictly forbidden. Those who did were often sent out of the country or put in prison. Banda's government was criticized by groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International for how it treated people. After he was removed from power, Banda was put on trial for serious charges.

During his rule, Banda was one of the few African leaders after colonial times to keep friendly relations with Apartheid-era South Africa.

Malawi Becomes a Multi-Party Democracy

More and more people in Malawi, including churches, and other countries put pressure on the government. This led to a vote where Malawians decided if they wanted a multi-party democracy or to continue with a one-party state. On June 14, 1993, the people of Malawi voted strongly for a multi-party democracy.

Fair national elections were held on May 17, 1994, under a temporary constitution. This constitution became permanent the next year. Bakili Muluzi, leader of the United Democratic Front (UDF), was elected president. The UDF won 82 out of 177 seats in the National Assembly. They formed a government with the Alliance for Democracy (AFORD). This partnership ended in June 1996, but some AFORD members stayed in the government. President Muluzi received an honorary degree in 1995.

Malawi's new constitution (1995) removed the special powers that the Malawi Congress Party used to have. The country also started to make its economy more open and reformed its systems.

On June 15, 1999, Malawi held its second democratic elections. Bakili Muluzi was re-elected for a second five-year term as president. This happened even though the MCP and AFORD teamed up against the UDF.

After these elections, the country faced some unrest. Some Tumbuka, Ngoni, and Nkhonde Christian groups in the north were unhappy with the election of Bakili Muluzi, a Muslim from the south. There was conflict between Christians and Muslims of the Yao tribe (Muluzi's tribe). Property was damaged or stolen, and 200 mosques were burned.

Malawi in the 21st Century

In 2001, the UDF had 96 seats in the National Assembly, AFORD had 30, and the MCP had 61. Six seats were held by independent members who were part of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) opposition group. The NDA was not an official political party at that time. The National Assembly had 193 members, including 17 women.

Malawi had its first peaceful change between democratically elected presidents in May 2004. The UDF's candidate, Bingu wa Mutharika, won against MCP candidate John Tembo and Gwanda Chakuamba. However, the UDF did not win most of the seats in Parliament this time. They gained a majority by forming a "government of national unity" with several opposition parties.

Bingu wa Mutharika left the UDF party on February 5, 2005. He said he had disagreements with the UDF, especially about his fight against corruption. He won a second term in the 2009 election as the head of a new party, the Democratic Progressive Party. In April 2012, Mutharika died from a heart attack. The vice-president, Joyce Banda (not related to Hastings Banda), became president.

In the 2014 Malawian general election, Joyce Banda lost and was replaced by Peter Mutharika, the brother of the former president. In the 2019 Malawian general election, President Peter Mutharika won by a small margin and was re-elected. However, in February 2020, the Malawi Constitutional Court canceled the result because of problems and widespread fraud. In May 2020, the Malawi Supreme Court agreed with this decision and announced a new election would be held on July 2. This was the first time an election was legally challenged in Malawi. Opposition leader Lazarus Chakwera won the 2020 Malawian presidential election and became the new president of Malawi.

In August 2021, the Constitutional Court looked at an appeal from Peter Mutharika's Democratic Progress Party. He asked for the 2020 presidential election to be canceled because four of his representatives were not allowed to be on the Electoral Commission. However, the court dismissed this challenge in November 2021.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Malaui para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Malaui para niños

- Heads of Government of Malawi

- History of Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- List of heads of state of Malawi

- Politics of Malawi

- Lilongwe history and timeline

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |