Amnesty International facts for kids

|

|

| Founded | July 1961 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Founders |

|

| Type |

|

| Headquarters | London, WC1 United Kingdom |

| Location |

|

| Services | Protecting human rights |

| Fields | Media attention, direct-appeal campaigns, research, lobbying |

|

Members

|

More than ten million members and supporters |

| Agnès Callamard | |

|

Employees

|

3,600 |

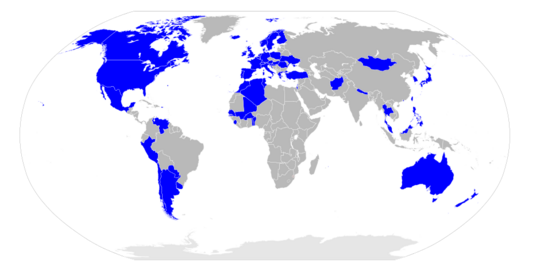

Amnesty International, often called Amnesty or AI, is a global group that works to protect human rights. It is a non-governmental organization, which means it is not part of any government. Its main office is in the United Kingdom, and it has over ten million members and supporters all over the world.

The group's goal is to create a world where everyone enjoys the rights listed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This important document says that all people have basic rights and freedoms. Amnesty International is often mentioned in the news and by world leaders for its work on human rights.

AI was started in London in 1961 by a lawyer named Peter Benenson. He was inspired to act after reading about two students in Portugal who were jailed for making a toast to freedom. He wrote an article called "The Forgotten Prisoners" to bring attention to people jailed for their beliefs. These people are called "prisoners of conscience."

At first, AI focused on helping these prisoners. Later, it also began working to stop unfair trials and torture. In 1977, the group won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work. Today, Amnesty International continues to speak out against human rights abuses and pushes governments to follow international laws.

Contents

History of Amnesty International

How It All Started in the 1960s

Amnesty International was founded in July 1961 by Peter Benenson, an English lawyer. He got the idea while riding the London Underground in 1960. He read a story about two students in Portugal who were sent to prison for seven years just for "toasting to liberty." At the time, Portugal had a strict government that punished people who disagreed with it.

Benenson felt that it was wrong for people to be jailed for their opinions. He wrote an article called "The Forgotten Prisoners" that was published in The Observer newspaper on May 28, 1961. The article asked people to take action to help those who were "imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government."

This article launched the "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961." The goal was to get the public to support these individuals, who Benenson called "Prisoners of Conscience." The appeal was a huge success and was printed in newspapers around the world. By 1962, the organization was officially named Amnesty International.

In the mid-1960s, AI grew quickly. It set up offices, called "Sections," in many countries. The group decided it would not support prisoners who had used violence to achieve their goals, like Nelson Mandela. Instead, it focused on peaceful activists. AI also started helping prisoners' families and sending people to watch trials to make sure they were fair.

Growing in the 1970s and 1980s

By 1979, Amnesty International's membership had grown from 15,000 to 200,000. The group worked with the United Nations to create better rules for how prisoners should be treated. In 1977, AI won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work against torture.

To raise money and awareness, AI's British Section started a series of comedy shows called The Secret Policeman's Balls. These shows featured famous comedians, including members of Monty Python. Later, famous musicians also performed at these events.

In the 1980s, AI organized two big music tours to spread its message about human rights. The 1986 Conspiracy of Hope tour in the U.S. and the 1988 Human Rights Now! world tour featured some of the biggest music stars of the time. These concerts helped bring the cause of human rights to a huge audience.

Working for Justice in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Amnesty continued to grow, reaching over seven million members in more than 150 countries. The organization pushed for the creation of a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and an International Criminal Court. Both were later established.

AI brought attention to human rights problems in specific places and for certain groups. For example, it urged the government in South Africa to investigate police abuse during apartheid. It also focused on the rights of refugees, women, and minorities.

In 1995, AI tried to run ads about the Shell Oil Company's connection to the execution of activist Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria. However, many newspapers and ad companies refused to run the ads because Shell was a major customer. This showed how difficult it can be to challenge powerful companies.

Facing New Challenges in the 2000s

After the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, AI's work became even more challenging. The group argued that protecting human rights was essential for security, not a barrier to it.

The new Secretary General, Irene Khan, spoke out against the U.S. government's detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. She compared it to a Soviet-era prison camp, which caused a lot of debate.

During this decade, AI also focused on ending violence against women and controlling the global weapons trade. In 2007, the group decided to support a woman's right to make decisions about her health in certain difficult situations.

In 2009, AI released a report on the conflict in Gaza. It accused both Israeli forces and the Palestinian group Hamas of committing war crimes. The report said that Israeli soldiers had killed many civilians and used Palestinians as human shields.

Recent Work in the 2010s

In 2014, Amnesty International sent a team of human rights activists to Ferguson, Missouri, in the U.S. This was the first time AI had sent such a team to the United States. They were there to observe protests following the police shooting of Michael Brown and to train local activists in non-violent protest.

In 2016, AI called for Saudi Arabia to be suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council. The group said that Saudi Arabia's human rights record was getting worse and that it had unlawfully killed civilians in the conflict in Yemen.

In 2018, the Indian government raided AI's office in Bengaluru. The government claimed the group had broken laws about receiving money from other countries. AI said this was an attempt to silence organizations that question the government.

In 2019, a report found serious problems with the work environment at Amnesty International, including bullying. This came after two staff members died. The organization's leadership team offered to resign in response to the report.

Amnesty International in the 2020s

In 2020, Amnesty International closed its offices in India after the government froze its bank accounts. The group also reported on human rights abuses in Belarus, Nigeria, and Angola.

In February 2022, AI released a report accusing Israel of committing apartheid against Palestinians. The report said Israel had a system of "oppression and domination" against the Palestinian people. The Israeli government called the report false, while Palestinian leaders said it described the "cruel reality" they faced.

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia closed Amnesty International's office in Moscow, along with those of other international organizations.

In December 2024, Amnesty stated that Israel was committing genocide in Gaza during its war there. In January 2025, AI suspended its own Israeli branch for two years. The group said there was evidence of racism against Palestinians within the branch and that it had failed to accept AI's reports on apartheid and genocide.

How Amnesty International is Organized

Amnesty International is mostly made up of volunteers, with a small number of paid staff. In countries where AI has a strong presence, it has offices called "sections."

The organization has three main parts:

- The Global Assembly: This is the highest decision-making body. Representatives from all the national sections meet every year to vote on important issues.

- The International Board: This is a group of eight members who oversee the organization. They are elected by the Global Assembly.

- The International Secretariat: This is the main office that manages the day-to-day work. It does most of the research, plans campaigns, and is led by the Secretary General.

Secretaries General

The Secretary General is the leader of Amnesty International's International Secretariat.

| Secretary General | Office | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Peter Benenson | 1961–1966 | Britain |

| Eric Baker | 1966–1968 | Britain |

| Martin Ennals | 1968–1980 | Britain |

| Thomas Hammarberg | 1980–1986 | Sweden |

| Ian Martin | 1986–1992 | Britain |

| Pierre Sané | 1992–2001 | Senegal |

| Irene Khan | 2001–2010 | Bangladesh |

| Salil Shetty | 2010–2018 | India |

| Kumi Naidoo | 2018–2020 | South Africa |

| Julie Verhaar | 2020–2021 (Acting) | |

| Agnès Callamard | 2021–present | France |

Main Goals and Principles

Amnesty International's main principle is to help prisoners of conscience. These are people who are jailed for peacefully expressing their beliefs. The group also believes in gathering facts carefully and staying neutral in political debates.

Amnesty International believes the death penalty is the ultimate denial of human rights and is against it in all cases.

The organization focuses on six key areas:

- Rights of women, children, minorities, and indigenous peoples

- Ending torture

- Abolishing the death penalty

- Rights of refugees

- Rights of prisoners of conscience

- Protecting human dignity

Cultural Impact

Human Rights Concerts

Amnesty International has staged many famous concerts to raise awareness about human rights. The first major tour was A Conspiracy of Hope in 1986. It featured artists like U2, Sting, and Peter Gabriel.

In 1988, the Human Rights Now! tour celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This world tour included stars like Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Tracy Chapman, and Youssou N'Dour. These concerts helped bring Amnesty's message to millions of people.

The Amnesty Candle

The logo of Amnesty International is a candle surrounded by barbed wire. It was inspired by the proverb, "Better to light a candle than curse the darkness."

The candle represents hope and the group's work to shine a light on injustice. The barbed wire symbolizes the suffering of people who are unfairly put in jail. The logo was designed in 1963 by Diana Redhouse.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Amnistía Internacional para niños

In Spanish: Amnistía Internacional para niños

- Ambassador of Conscience Award

- Amnesty International UK Media Awards

- List of Amnesty International UK Media Awards winners

- List of peace activists

- Scholars at Risk

- World Coalition Against the Death Penalty

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |