Ken Saro-Wiwa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

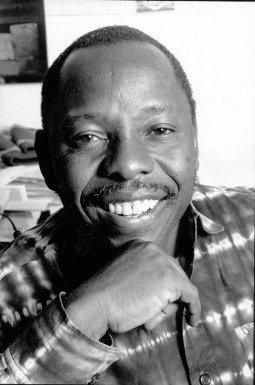

Ken Saro-Wiwa

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Kenule Beeson Saro-Wiwa

10 October 1941 Bori, Colonial Nigeria

|

| Died | 10 November 1995 (aged 54) Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

|

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Occupation |

|

| Movement | Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People |

| Children | 5, including Ken Wiwa, Zina and Noo |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Owens Wiwa (brother) |

| Awards |

|

Kenule Beeson "Ken" Saro-Wiwa (10 October 1941 – 10 November 1995) was a brave Nigerian writer, TV producer, and environmental activist. He was a member of the Ogoni people, a small group in Nigeria. Their homeland, Ogoniland, in the Niger Delta, has been a target for oil drilling since the 1950s. This has caused serious environmental damage from oil waste.

Ken Saro-Wiwa became a leader of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). He led a peaceful campaign against the pollution of Ogoni land and water. This pollution was caused by big oil companies, especially Royal Dutch Shell. He also spoke out against the Nigerian government for not making these companies follow environmental rules.

At the height of his peaceful efforts, he was arrested and put on trial by a special military court. He was accused of being involved in the deaths of some Ogoni chiefs. In 1995, the military government of General Sani Abacha executed him. His execution shocked the world and led to Nigeria being suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations for over three years.

Ken Saro-Wiwa: A Champion for the Environment

Who Was Ken Saro-Wiwa?

Ken Saro-Wiwa was a powerful voice for his people and the environment. He used his writing and his activism to fight for justice. He believed that the Ogoni people should have a fair share of the oil money from their land. He also wanted their land to be cleaned up from years of pollution. His story shows how one person can stand up against powerful forces for what is right.

Early Life and Education

Kenule Saro-Wiwa was born in Bori, Nigeria, on 10 October 1941. His father was Chief Jim Wiwa. Ken was a very bright student from a young age. He went to primary school in Bori and then to Government College Umuahia. He was excellent in subjects like History and English.

He later earned a scholarship to study English at the University of Ibadan. There, he explored his love for academics and culture. He even worked with a drama group that performed in different cities. After university, he briefly taught at the University of Lagos.

During the Nigerian Civil War, he supported the Nigerian government. He became a Civilian Administrator for the city of Bonny. Later, he served as a commissioner in Rivers State. His famous novel, Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English (1985), tells the story of a young village boy joining the army during the war. He also wrote On a Darkling Plain (1989), which shares his experiences during the war. Ken Saro-Wiwa was also a successful businessman and TV producer. His funny TV show, Basi & Company, was very popular, with millions of viewers.

In the early 1970s, he was a Commissioner for Education. But he was removed in 1973 because he supported the Ogoni people's right to govern themselves. In the 1980s, he focused on his writing and TV work. He tried to enter politics in 1977 but did not win.

In 1987, he returned to politics. He was asked to help Nigeria become a democracy. However, he soon realized that the plans were not real. He resigned because he felt the government was not serious about democracy.

His Fight for the Ogoni People

In 1990, Ken Saro-Wiwa started focusing on human rights and environmental issues. He especially cared about the land of the Ogoni people. He was a key member of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). This group fought for the rights of the Ogoni people.

The Ogoni Bill of Rights

MOSOP wrote the Ogoni Bill of Rights. This document listed their demands. They wanted more control over their own affairs. They also asked for a fair share of the money from oil extraction. Most importantly, they demanded that the oil companies clean up the environmental damage. MOSOP strongly opposed the pollution caused by Royal Dutch Shell.

Standing Up to Power

In 1992, the Nigerian military government arrested Ken Saro-Wiwa. He was held for several months without a trial. From 1993 to 1995, he was a leader in the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO). This group helps indigenous peoples and minorities protect their rights.

In January 1993, MOSOP organized peaceful marches. About 300,000 Ogoni people marched, which was more than half of their population. These marches brought international attention to their struggles. Later that year, the Nigerian government sent its military to occupy the region.

Arrest and Legacy

Ken Saro-Wiwa was arrested again in June 1993 but released after a month. On May 21, 1994, four Ogoni chiefs were killed. Ken Saro-Wiwa was arrested and accused of causing these deaths. He denied the charges. He was held for over a year before being found guilty by a special court. He was sentenced to death. Eight other MOSOP leaders, known as the Ogoni Nine, were also sentenced to death.

Many human rights groups criticized the trial. They said it was unfair and rigged by the government. Some witnesses later admitted they were bribed to give false testimony. Despite this, the sentences were upheld.

Just before his execution, Ken Saro-Wiwa received the Right Livelihood Award and the Goldman Environmental Prize. These awards recognized his bravery and his work. On November 10, 1995, Ken Saro-Wiwa and the other Ogoni Nine were executed by hanging.

His death caused a huge international outcry. The United Nations General Assembly condemned the executions. Many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, criticized Nigeria. Nigeria was suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations. Ken Saro-Wiwa's execution helped start the global movement for business and human rights.

Remembering Ken Saro-Wiwa

Many people and organizations have honored Ken Saro-Wiwa's memory.

Art and Memorials

- A special memorial was unveiled in London on November 10, 2006. It is a sculpture shaped like a bus. It was created by Nigerian artist Sokari Douglas Camp.

Awards and Recognition

- The Association of Nigerian Authors has a Ken Saro-Wiwa Prize for Prose.

- He is listed as a "Writer hero" by The My Hero Project.

- The magazine Foreign Policy named him as someone who deserved the Nobel Peace Prize.

Books and Music

- His execution inspired the novel The Other Side of Truth (2000) by Beverley Naidoo.

- Richard North Patterson wrote a novel, Eclipse (2009), based on Saro-Wiwa's life.

- Many musicians have dedicated songs to him, including Il Teatro degli Orrori, Ultra Bra, King Cobb Steelie, and Nneka.

Places Named After Him

- The city of Amsterdam named a street after him: the Ken Saro-Wiwastraat.

- A room at the Liverpool Guild of Students is named in his honor.

- An ant species, Zasphinctus sarowiwai, was named after him in 2017.

- The Governor of Rivers State, Ezenwo Nyesom Wike, renamed the Rivers State Polytechnic after Saro-Wiwa.

Ken Saro-Wiwa Foundation

The Ken Saro-Wiwa Foundation was started in 2017. It works to help entrepreneurs in Port Harcourt get basic resources like electricity and internet. The foundation also gives out the Ken Junior Award. This award is named after Saro-Wiwa's son, Ken Wiwa, who passed away in 2016. It celebrates new technology companies in Port Harcourt.

Personal Life

Ken Saro-Wiwa and his wife Maria had five children. They grew up in the United Kingdom. His children include Ken Wiwa and Noo Saro-Wiwa, who are both writers. His twin daughter, Zina Saro-Wiwa, is a journalist and filmmaker. He also had two other daughters, Singto and Adele, and another son, Kwame.

See also

In Spanish: Ken Saro-Wiwa para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |