Nigerian Civil War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nigerian Civil War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the decolonisation of Africa | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by:

|

Supported by:

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Foreign mercenaries:

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

45,000–100,000 combatants killed 500,000–2,000,000 Biafran civilians died from famine during the Nigerian naval blockade 2,000,000–4,500,000 displaced, 500,000 of whom fled abroad |

|||||||

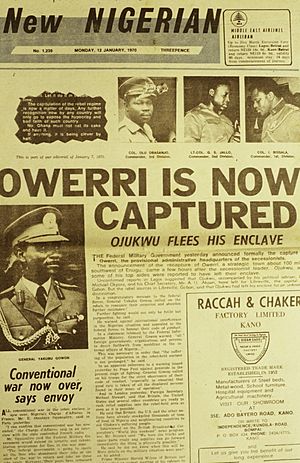

The Nigerian Civil War (July 6, 1967 – January 15, 1970) was also called the Nigerian–Biafran War or the Biafran War. It was a civil war fought between Nigeria and a state called Republic of Biafra. Biafra had declared itself independent from Nigeria in 1967.

General Yakubu Gowon led Nigeria. Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu led Biafra. Biafra wanted to be its own country because the Igbo ethnic group, who lived there, felt they could not live peacefully with the Nigerian government. This government was mostly controlled by the Muslim Hausa-Fulani people from Northern Nigeria.

The war happened because of old problems. These included political, economic, ethnic, cultural, and religious tensions. These problems existed even before Nigeria became independent from the United Kingdom in 1960. In 1966, a military takeover (coup), a counter-takeover, and attacks against Igbo people in Northern Nigeria directly led to the war.

Controlling the valuable oil in the Niger Delta was also very important. This was a big reason why France strongly supported Biafra. Within a year, Nigerian troops surrounded Biafra. They captured oil areas and the city of Port Harcourt.

Nigeria then set up a blockade around Biafra. This stopped food and supplies from getting in. This blockade caused many Biafran civilians to starve. During the two-and-a-half-year war, about 100,000 soldiers died. Between 500,000 and 2 million Biafran civilians died from starvation.

The Nigerian Civil War was one of the first wars shown on TV around the world. In 1968, pictures of starving Biafran children were seen everywhere. People in other countries felt very sad for the Biafrans. This led to a big increase in money and importance for international aid groups, called non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Biafra received help from people around the world through the Biafran airlift. This event later inspired the creation of Doctors Without Borders. The United Kingdom and the Soviet Union supported Nigeria. France, Israel (after 1968), and some other countries supported Biafra. The United States officially stayed neutral.

The war showed problems with pan-Africanism, which is the idea of all African people uniting. It showed that African peoples are too different to always find common ground. It also showed early weaknesses of the Organization of African Unity. After the war, the Igbo people were often left out of politics. Nigeria has not had an Igbo president since the war. This makes some Igbo people feel they are still being punished. This has led to new Igbo groups wanting their own country, like the Indigenous People of Biafra.

Contents

Why the War Started: Background

Nigeria's Diverse Ethnic Groups

The Nigerian Civil War has roots in how Nigeria was formed. In 1914, the British colonial government joined the Northern and Southern parts of Nigeria. This was supposed to make it easier to rule. However, the British did not consider the many different cultures and religions of the people. Competition for power and money made these differences worse.

Nigeria became independent from the United Kingdom on October 1, 1960. It had about 45 million people from over 300 different ethnic groups. The three largest groups were the Igbo in the southeast, the Hausa-Fulani in the north, and the Yoruba in the southwest. Even though these groups had their own homelands, many people lived in cities across Nigeria.

The Hausa-Fulani in the north were mostly Muslim. They had a traditional system of rule by religious leaders called emirs. The Yoruba in the southwest also had monarchs, called Obas. But their system allowed people to move up in society based on what they earned, not just who their family was.

The Igbo people in the southeast were different. They lived in communities where decisions were made by everyone. They were very active in their political system. They believed in achieving success through hard work.

The British colonial government made these differences even bigger. In the north, they ruled through the emirs. This kept the traditional system strong. Christian missionaries were not allowed in the north. So, the area stayed mostly closed to European culture.

In the west, missionaries quickly brought Western education. The Yoruba people were the first to adopt Western ways. They became the first African civil servants, doctors, and lawyers.

The Igbo people in the east also strongly embraced Western education. They became mostly Christian. Because there were so many people in the Igbo homeland, many Igbos moved to other parts of Nigeria to find work. By 1966, the differences between northerners and the Igbo had grown. This was due to new differences in education and economic class.

Politics & Money in Nigeria

The British divided Nigeria into three regions: North, West, and East. This made the economic and political differences among Nigeria's ethnic groups worse. The North had more people than the other two regions combined. There were also many reports of cheating during Nigeria's first population count. Because of its larger population, the Northern Region got more seats in the government.

Each region's main ethnic group formed its own political party. The Northern People's Congress (NPC) was in the North. The Action Group was in the West. The National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) was in the East. These parties were mostly based in one region and one tribe. This was a big reason why Nigeria later fell apart.

When Nigeria was formed in 1914, the British ruled indirectly. This meant they worked with local leaders. This system was used in the North and then extended to the South. This new system was different for the Igbo people. Educated Nigerians started asking for more rights and independence.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Igbo and Yoruba parties pushed for independence from Britain. Northern leaders were worried that independence would mean the more Westernized people in the South would control everything. They wanted British rule to continue. To accept independence, they demanded that the North keep its majority in the government. Igbo and Yoruba leaders agreed to this to get independence.

However, the two Southern regions had big cultural differences. This caused problems between their political parties. The Action Group wanted a loose union of regions. Each region would control its own land. The NCNC wanted a strong, united country. The Action Group even threatened to leave Nigeria if its demands were not met. This idea of regions being able to leave was rejected. If it had been allowed, the civil war might have been avoided.

Tensions between the North and South led to riots. In 1945, 300 Igbo people died in the Jos Riot. In 1953, there was fighting in Kano. Political parties focused on their own regions. This made the federal government weak and disunited.

In 1946, the British divided the Southern Region into West and East. Each government collected money from resources in its area. This changed in 1956 when oil was found in the East. A new rule said that oil money would be shared. 50% went to the region where the oil was found. 20% went to the federal government. 30% went to other regions. The British government encouraged unity in the North and division in the South. After independence, the Nigerian government also created a new Mid-Western Region. This was in an area with oil.

Nigeria's First Government & Military Issues

Early Independence & Political Problems

Nigeria became fully independent on October 1, 1960. Its first government, called the First Republic, began on October 1, 1963. The first prime minister, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, was from the North. He teamed up with the NCNC party. Its leader, Nnamdi Azikiwe, became President. The Action Group, from the West, was the main opposition.

Workers were unhappy with low pay and bad conditions. They saw politicians in Lagos living well. Strikes became common in 1963. A nationwide strike happened in June 1964. Strikers won higher wages. This strike made tensions worse between the army and ordinary people. Many saw the government as corrupt.

The 1964 elections made ethnic and regional divisions clear. People were angry at politicians. Violence spread across the country. Some people fled the North and West. The North seemed to control the political system. This chaos made some military members think about taking strong action.

Britain made a lot of money from Nigeria's mining and trade. A British company controlled 41.3% of Nigeria's foreign trade. Nigeria became the tenth-biggest oil exporter. It produced 516,000 barrels of oil per day.

Army's Role & Changes

Nigeria's army, inherited in 1960, was meant to help the police. It was not trained for war. An Indian historian called it "a glorified police force." The army did not do field training and lacked heavy weapons. Before 1948, Nigerians could not be officers. After 1948, some promising Nigerians could train as officers in England.

At independence in 1960, only 57 of 257 officers were Nigerian. The British believed that people from northern Nigeria, like the Hausa, made better soldiers. They thought southerners, like the Igbo and Yoruba, were too soft. So, northerners made up 62% of the army by 1958.

In 1958, this policy changed. Northerners would make up 50% of soldiers. Southerners would make up 25% each. Northerners felt angry about this change. After independence, more Nigerians could become officers. Southerners were generally better educated. They were more likely to become officers. This made northerners even more resentful.

To make the army more Nigerian, British officers were sent home. More Nigerians were promoted. This meant educational standards for officers were lowered. Many young, ambitious officers joined. A group of Igbo officers started planning to overthrow the government. They believed the northern prime minister was taking oil wealth from the southeast.

Military Takeovers & Igbo Persecution

Military Coups Shake Nigeria

On January 15, 1966, Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, and other junior army officers tried to take over the government. They killed the prime minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, and the northern premier, Sir Ahmadu Bello. Bello's wife and northern officers were also killed. The president, Sir Nnamdi Azikiwe, an Igbo, was away. He did not return until after the coup. Many suspected that Igbo plotters warned him and other Igbo leaders.

The premier of the Western region and Yoruba senior officers were also killed. This coup was called the "Coup of the Five Majors." It was the first coup in Nigeria's new democracy. The plotters said they were fighting election fraud. They wanted to break the North's power. But their attempt to take power failed in the South.

Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, an Igbo and loyal army leader, stopped the coup in the South. He became head of state on January 16. Ironsi stopped the constitution and closed parliament. He changed the government to be more centralized. He appointed a northern colonel to govern the Northern Region. He also released northern politicians from jail.

Ironsi did not put the coup plotters on trial. This was against military law. Many northern and western officers advised him to do so. Instead, the plotters stayed in the military with full pay. Some were even promoted. Many saw the coup as helping the Igbo people. No major Igbo leaders were harmed. Most of the plotters were Igbo. The military and political leaders of the West and North were killed.

This led to suspicion of an "Igbo conspiracy." Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu became military governor of the Eastern Region. On May 24, 1966, the government issued a decree. It would replace the federal system with a more centralized one. The North found this unacceptable.

Northern soldiers mutinied on July 29, 1966. This started a counter-coup. Ironsi was killed. Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon became the new leader. Gowon was chosen as a compromise. He was from the North, a Christian, and from a smaller tribe. He had a good reputation.

Gowon faced threats from the East, North, and West. The counter-coup plotters thought about leaving the country. But ambassadors from the UK and US urged Gowon to keep control. Gowon agreed. He canceled the centralization decree and brought back the federal system.

Attacks on Igbo People

From June to October 1966, terrible attacks happened in the North. These attacks, called pogroms, killed an estimated 8,000 to 30,000 Igbo people. Half of them were children. More than a million Igbo people fled to the Eastern Region. September 29, 1966, was known as 'Black Thursday.' It was the worst day of these killings.

A professor of history, Murray Last, was in Zaria city after the first coup. He said there was relief on campus at first. But later, he saw anger. Igbo traders were mocking Hausa traders about the death of their leader. They were telling Hausa people that rules had changed.

The government also started planning to stop trade with the Eastern Region. This blockade began fully in 1967.

Biafra Declares Independence

Many refugees arrived in Eastern Nigeria. This made the situation very difficult. Ojukwu, representing Eastern Nigeria, and Gowon, representing Nigeria, held talks. They signed the Aburi Accord in Ghana. They agreed to a looser Nigerian union. But Gowon delayed the announcement and later went back on the agreement.

On May 27, 1967, Gowon divided Nigeria into twelve states. This split the Eastern Region into three parts. These were the South Eastern State, Rivers State, and East Central State. The Igbo people, mostly in the East Central State, would lose control of most of the oil. The oil was in the other two areas.

The Nigerian government immediately stopped all shipping to and from Biafra. But they did not stop oil tankers. Biafra quickly tried to collect oil money from companies in its area. When Shell-BP agreed to pay Biafra, the Nigerian government stopped oil shipping too. This blockade put Biafra at a disadvantage from the start of the war.

Biafra was very short on weapons. But it was determined to fight. Only five countries officially recognized Biafra. These were Tanzania, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Zambia, and Haiti. The United Kingdom supplied heavy weapons to Nigeria. They said it was to keep Nigeria united. But it was also to protect their oil supply and Shell-BP's investments. France supplied weapons to Biafra. These weapons often came through neighboring countries. The large supply of weapons from the UK was a big factor in Nigeria winning the war.

Several peace talks were held. The most important was in Aburi, Ghana. Ojukwu said the Nigerian government broke its promises. Gowon's advisers felt he had done all he could. The Eastern Region was not ready for war. It had fewer soldiers and weapons than Nigeria. But Biafra had the advantage of fighting in its homeland. Most Easterners supported them.

The United Kingdom and the Soviet Union supported Nigeria. They provided military supplies. The Nigerian Army in 1967 was not ready for war. It was mostly an internal security force. Most officers cared more about social life than training. The killings during the 1966 coups had removed many experienced officers.

The same problems affected the Biafran Army. They also lacked experienced officers. Ojukwu did not trust many former Nigerian officers who joined Biafra. He had many of them executed. This hurt the morale of Biafran officers. Losing a battle often meant death for a Biafran officer. Ojukwu also created special units outside the normal army command. This was because he feared a coup.

The War Begins

The war started on July 6, 1967. Nigerian troops advanced into Biafra. Biafra's plan worked: Nigeria started the war, and Biafra was defending itself. The Nigerian Army attacked from the north. They faced strong resistance. The town of Nsukka fell on July 14. Garkem was captured on July 12.

Biafra's Attack

Biafra launched its own attack. On August 9, Biafran forces crossed into Nigeria's Mid-Western state. They passed through Benin City. They advanced west until August 21. They were stopped at Ore, about 130 miles east of Lagos. This attack was led by Lt. Col. Banjo. It met little resistance. The Mid-Western state was easily taken. This was because Igbo soldiers had returned to their regions to avoid killings.

General Gowon responded by forming a new division. This division would expel Biafrans from the Mid-Western state. It would also defend the Western state and attack Biafra. Gowon declared "total war." He said Nigeria would mobilize its entire population. The Nigerian Army grew from 7,000 to 200,000 men by 1969. Biafra started with only 230 soldiers. By 1969, Biafra had 90,000 soldiers.

As Nigerian forces retook the Mid-Western state, Biafra declared it the Republic of Benin on September 19. It lasted only one day. Benin City was retaken by Nigerians on September 22. But Biafra had achieved its goal of tying down Nigerian troops. Gowon also launched an attack into Biafra from the south. This was led by Colonel Benjamin Adekunle, known as the Black Scorpion.

Nigeria's Counter-Attack

The Nigerian attack was divided into two brigades. The first brigade advanced on the Ogugu–Ogunga–Nsukka road. The second advanced on the Gakem–Obudu–Ogoja road. By July 10, 1967, the first brigade had taken all its areas. By July 12, the second brigade had captured Gakem, Ogudu, and Ogoja.

Egypt sent six bombers to help Nigeria. These planes were flown by Egyptian pilots. The Egyptians often bombed Red Cross hospitals, schools, and markets. This made the world feel more sympathy for Biafra.

Enugu was the center of the rebellion. Nigeria believed capturing it would end the fight. Plans to capture Enugu began on September 12, 1967. On October 4, the Nigerian 1st Division captured Enugu. Ojukwu escaped by disguising himself. Many Nigerians hoped Enugu's capture would make Igbo leaders end their support for secession. But this did not happen. Ojukwu moved his government to Umuahia.

The fall of Enugu briefly confused Biafran propaganda. But on October 23, Biafra's radio said Ojukwu would keep fighting. He blamed the loss on "saboteurs."

Nigerian soldiers under Murtala Mohammed killed 700 civilians when they captured Asaba. Nigerians tried three times to cross the River Niger in October. They lost thousands of troops and many tanks. The first attempt on October 12 cost Nigeria over 5,000 soldiers.

Operation Tiger Claw happened from October 17–20, 1967. Nigerians invaded Calabar led by Benjamin Adekunle. Biafrans were led by Col. Ogbu Ogi and a foreign mercenary, Lynn Garrison. Biafran positions were bombed by the Nigerian air force. By October 20, Garrison's forces left. Col. Ogi surrendered. On May 19, 1968, Port Harcourt was captured. With these captures, the world saw Nigeria's strength.

Biafran propaganda always blamed defeats on "saboteurs" within their army. Officers were encouraged to report suspected "saboteurs." Biafran officers were often executed by their own side. Ojukwu did not trust many former Nigerian Igbo officers. He saw them as rivals. He needed people to blame for defeats. Death was the usual punishment for officers who lost a battle.

Oil & International Support

Control Over Oil Production

Oil was first found in Nigeria in 1937 by Shell-BP. To control the oil in the Eastern region, Nigeria stopped shipping there. But oil tankers were still allowed. Biafra asked Shell-BP for money from the oil. Shell-BP paid Biafra £250,000. When Nigeria found out, it stopped oil shipping too. Nigeria told Shell-BP to stop working in Biafra. Nigeria then took over from the company.

By late July 1967, Nigerian troops captured Bonny Island. This gave them control of important Shell-BP oil facilities. Oil production started again in May 1968 when Nigeria captured Port Harcourt. The facilities were damaged and needed repair. Oil production continued but at a lower level. By 1969, a new terminal at Forçados was finished. Oil production rose to 540,000 barrels per day. In 1970, it doubled to 1.08 million barrels per day. This oil money helped Nigeria buy more weapons and hire mercenaries. Biafra could not compete with this economic power.

Who Helped Whom: International Involvement

The United Kingdom wanted to keep getting cheap oil from Nigeria. So, they focused on keeping oil production going. The war started just before the Suez Canal was blocked. This made Nigerian oil even more important to the UK. At first, the UK waited to see who would win. Nigeria's military was small. But Biafra was also weak. So, the two sides seemed evenly matched.

The UK supported Nigeria. But they warned Nigeria not to damage British oil facilities in the East. These oilworks controlled 84% of Nigeria's oil. Two-thirds of this oil came from the Eastern region. Two-fifths of all Nigerian oil went to the UK. In 1967, 30% of the UK's oil imports came from Nigeria.

Shell-BP was asked by Nigeria not to pay Biafra. Their lawyers said paying Biafra was fine if Biafra controlled the region. But the British government said paying Biafra would upset Nigeria. Shell-BP paid Biafra. Then Nigeria blocked oil exports. Shell-BP and the British government decided to support Nigeria. They thought Nigeria would win. Shell-BP continued to support Nigeria. They even gave Nigeria £5.5 million to buy more British weapons.

After Nigerian forces captured Bonny on July 25, 1967, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson decided to give military aid to Nigeria. He believed Nigeria would win. The UK secretly gave Nigeria weapons and military information. They may have also helped Nigeria hire mercenaries. The BBC also reported in favor of Nigeria.

In the UK, a humanitarian campaign for Biafra started in June 1968. Charities like Oxfam and Save the Children Fund raised a lot of money.

France's Role

France gave weapons, mercenary fighters, and other help to Biafra. They also spoke up for Biafra internationally. President Charles de Gaulle called it "Biafra's just and noble cause." But France did not officially recognize Biafra as a country. France supplied Biafra with old German and Italian weapons. These were sent through nearby countries like Ivory Coast. France also sold armored vehicles to Nigeria.

France's involvement was part of its strategy in West Africa. Nigeria was a base for British influence. France and Portugal used nearby countries like Ivory Coast to send supplies to Biafra. France had also supported a breakaway province in the Congo before.

Economically, France wanted oil drilling contracts. A French oil company, SAFRAP, had claims to 7% of Nigerian oil. A CIA analyst in 1970 said France's support was for oil. Biafra appreciated France's help. Ojukwu even suggested teaching French in Biafran schools.

France led the way in political support for Biafra. Portugal also sent weapons. These deals were made through a group in Paris. French-aligned Gabon and Ivory Coast recognized Biafra in May 1968. De Gaulle personally gave money for medicine. The French government declared an arms embargo. But they still sent arms to Biafra disguised as humanitarian aid. In July, they tried to get the public more involved in helping. Pictures of starving children and claims of genocide filled French media. On July 31, 1968, De Gaulle officially supported Biafra.

Soviet Union's Support

The Soviet Union strongly supported Nigeria. They saw it as similar to the Congo situation. Nigeria needed more aircraft. The UK and US would not sell them. So, Gowon accepted a Soviet offer in 1967. They sold Nigeria 17 MiG-17 fighter jets. About 200 Soviet technicians came to train Nigerians. The MiG-17s were too complex for Nigerians to fly. So, Egyptian pilots flew them.

This arms deal was a turning point. It opened an arms supply from the Soviet Union to Nigeria. The possibility of Soviet influence in Nigeria made the UK increase its arms supply. This also stopped the US or Britain from recognizing Biafra.

The Soviet Union was interested in Nigeria's mineral resources and trade. The war was a way to build this relationship. The Soviets always said their weapons were "strictly for cash." In 1968, the USSR agreed to fund a dam on the Niger River. Soviet media first accused Britain of supporting Biafra. They changed their story when they saw Britain was helping Nigeria.

One reason for Soviet support was their opposition to breakaway movements. Before the war, the Soviets seemed to like the Igbos. But Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin said in 1967 that the Soviet people understood Nigeria's need to prevent the country from breaking apart.

The war greatly improved Soviet-Nigerian relations. Soviet cars appeared in Lagos. The USSR became a big buyer of Nigerian cocoa.

China's Involvement

The Soviet Union was a main supporter of Nigeria. Because of their rivalry, China supported Biafra. In September 1968, China's Xinhua Press Agency said China supported Biafra's fight for freedom. They said Biafra was fighting against Nigeria, which was supported by "Anglo-American imperialism and Soviet revisionism." China sent arms to Biafra through Tanzania. They sent about $2 million worth of arms in 1968–1969.

Israel's Position

Israel saw Nigeria as an important country in West Africa. They wanted good relations with Lagos. Nigeria and Israel started ties in 1957. In 1960, Israel opened a diplomatic office in Lagos. Israel gave Nigeria a $10 million loan. Israel also developed cultural ties with the Igbos. Some northern leaders in Nigeria did not like contact with Israel.

Israel did not sell arms to Nigeria until Ironsi came to power in 1966. This was seen as a good time to build relations. Thirty tons of mortar rounds were delivered in April.

The Eastern Region asked Israel for help in September 1966. Israel seemed to refuse. But they might have connected Biafran representatives with other arms dealers. In 1968, Israel started supplying Nigeria with arms. This was about $500,000 worth. Meanwhile, the situation in Biafra was called a genocide. The Israeli parliament debated this. Right-wing and left-wing groups supported Biafra.

In August 1968, the Israeli Air Force openly sent twelve tons of food aid to a nearby area outside Biafran airspace. Secretly, Mossad gave Biafra $100,000. They also tried to send weapons. Israel then secretly sent weapons to Biafra using Ivory Coast planes. African nations often supported Arab states against Israel. Israel did not want to upset African nations by openly supporting Biafra.

Egypt's Contribution

President Gamal Abdel Nasser sent pilots from the Egyptian Air Force to fight for Nigeria in August 1967. They flew the new MiG-17s. Egyptian pilots often bombed Biafran civilians without caring. This made Biafra gain more international sympathy. In 1969, Nigeria replaced the Egyptian pilots with more skilled East German pilots.

United States' Neutrality

The civil war began when Lyndon B. Johnson was US president. The US was officially neutral. Secretary of State Dean Rusk said Nigeria was "a responsibility of Britain." The US had interests aligned with Nigeria. But many Americans supported Biafra. The US also wanted to protect its $800 million investments in Nigeria.

The neutrality was not popular with everyone. A group supporting Biafra formed in the US. They wanted the US government to help Biafra more. Biafra became a topic in the 1968 US presidential election. On September 9, 1968, future president Richard Nixon called for action to help Biafra. He said starvation was happening.

Both Biafran officials and their US supporters hoped Nixon's election would change US policy. But when Nixon became president in 1969, he found he could do little. He only called for more peace talks. According to a political theorist, US support for Biafra would have angered Nigeria and other African nations. They saw the war as an internal matter. The Vietnam War also made US intervention in Biafra difficult. Despite this, Nixon personally supported Biafra.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger compared the Igbo people to Jews. He said they were "gifted, aggressive, Westernized; at best envied and resented, but mostly despised."

Gulf Oil Nigeria was the third major oil company. It produced 9% of Nigeria's oil before the war. Its operations were offshore, in federally controlled territory. So, it continued to pay Nigeria. Its operations were mostly undisturbed.

Canada's Observers

At Nigeria's request, Canada sent three observers. They investigated claims of genocide and war crimes. Major General W.A. Milroy and two other Canadian officers were there from 1968 to 1970.

African Union's Stance

Biafra asked for support from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). But OAU members generally did not want to support groups trying to break away. Countries like Ethiopia and Egypt supported Nigeria. They wanted to prevent revolts in their own countries. However, Biafra did get support from Tanzania, Zambia, Gabon, and Ivory Coast.

Foreign Fighters (Mercenaries)

Biafra hired foreign fighters, called mercenaries, for extra help. These mercenaries had fought in the Congo Crisis. German mercenary Rolf Steiner led Biafra's 4th Commando Brigade. He commanded 3,000 men. Welsh mercenary Taffy Williams led 100 Biafran fighters. Other mercenaries included an Italian, a Rhodesian, a Scotsman, an Irishman, and a Jamaican.

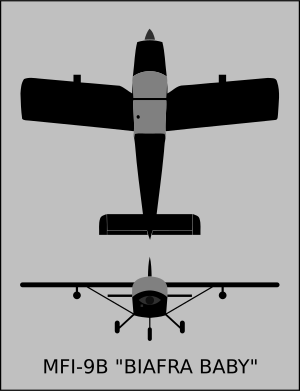

Polish-Swiss pilot Jan Zumbach created Biafra's air force. Canadian pilot Lynn Garrison, Swedish pilot Carl Gustaf von Rosen, and Rhodesian pilot Jack Malloch led Biafran air operations. They attacked Nigerian forces and delivered weapons and food. Portuguese pilots also flew for Biafra. Steiner also created a small navy using converted boats. These boats launched surprise raids for weapons and supplies.

People hoped mercenaries would help Biafra like they did in the Congo. But they were not very effective. The Nigerian military was much better trained. Some early successes happened, but over half of Steiner's brigade was destroyed in November 1968. Steiner became depressed and was replaced by Taffy Williams.

Even though Nigeria was a tough opponent, some mercenaries seemed to care about Biafra's cause. This is rare for mercenaries. Belgian mercenary Marc Goosens was killed fighting for Biafra. He reportedly hated the British government. Steiner claimed he fought for Biafra for idealistic reasons. He said the Igbo people were victims of genocide. But a journalist called him a militarist who just loved war.

After the war, Biafran chief of staff Philip Effiong was asked about the mercenaries. He said, "They had not helped. It would had made no difference if not a single one of them came to work for the secessionist forces."

The War's End & Its Impact

Biafra Surrounded

From 1968 on, the war became a stalemate. Nigerian forces could not advance much into Biafran areas. They faced strong resistance and defeats in places like Abagana and Umuahia. But a Nigerian attack from April to June 1968 began to close in on Biafra. They captured Port Harcourt on May 19, 1968. The blockade around Biafra led to a terrible humanitarian crisis. There was widespread hunger and starvation.

The Biafran government said Nigeria was using hunger and genocide to win. They asked for outside help. Private groups in the US, led by Senator Ted Kennedy, responded. No one was ever held responsible for the killings.

In September 1968, the Nigerian army planned a "final offensive." Biafran troops stopped it by the end of the year. In 1969, Biafra launched several attacks. In March, they recaptured Owerri. In May, they recaptured oil wells in Kwale. In July, Biafran forces launched a big land attack. Foreign pilots continued to fly in food, medicine, and weapons.

Swedish Count Carl Gustaf von Rosen was a notable mercenary. He led air attacks with small planes. His Biafran Air Force had three Swedes and two Biafrans. From May 22 to July 8, 1969, von Rosen's small force attacked Nigerian military airfields. They destroyed or damaged Nigerian Air Force jets. These jets were used to bomb Biafran villages daily. Biafran air attacks disrupted Nigerian air operations for a few months.

Nigeria used foreign aircraft, like Soviet MiG-17 and Il-28 bombers. Biafra also hired mercenaries. German-born Rolf Steiner and Welshman Taffy Williams stayed for the whole war.

Humanitarian Crisis & Aid

The attacks in September 1966 and the Igbo leaving northern Nigeria led to calls for the UN to end genocide. Awareness of the crisis grew in 1968. Information spread through religious groups, especially missionaries. Christian organizations noticed that Biafrans were Christian and the Nigerian government was Muslim. Groups like Joint Church Aid and Caritas helped.

The famine was caused by Nigeria's blockade of the Eastern region. A journalist, Frederick Forsyth, noted the main problem was lack of protein. Before the war, people ate dried fish from Norway. They also had local hogs, chicken, and eggs. The blockade stopped imports. Local protein ran out quickly. The diet became almost 100% starch.

Many volunteer groups organized the Biafran airlift. They flew food, medicine, and sometimes weapons into Biafra. Some claimed that planes carrying arms flew close to aid planes. This made it hard to tell them apart.

The American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive was formed in July 1968. It was started by former Peace Corps volunteers and college students. The Peace Corps volunteers had strong friendships with Igbo people. They wanted to help the Eastern Region.

Lynn Garrison helped Count Carl Gustav von Rosen. He showed how to drop bagged supplies without losing them. One sack of food was placed inside a larger sack. When it hit the ground, the inner sack broke, but the outer one kept the food safe. This method saved many Biafrans from starvation.

Bernard Kouchner was a French doctor who volunteered with the French Red Cross in Biafra. The Red Cross made volunteers sign an agreement to stay neutral. Kouchner and other doctors signed it.

The volunteers saw Nigerian army attacks on hospitals and civilians. They saw civilians being murdered and starved. Kouchner saw many starving children. When he returned to France, he criticized the Nigerian government and the Red Cross. He and other French doctors formed a new aid organization. They believed it should ignore politics and focus on victims. This group became Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in 1971.

The crisis made non-governmental organisations (NGOs) much more important and funded.

Media & Public Opinion

Media and public relations were very important in the war. Both sides needed outside support. Biafra hired a public relations firm in New York. But they gained more international sympathy when they hired Markpress in January 1968. Markpress was led by William Bernhardt. He was paid a lot and expected a share of Biafra's oil money.

Markpress showed the war as a fight for freedom by Catholic Igbos against Muslim northerners. This gained support from Catholics worldwide. They also accused Nigeria of genocide. Pictures of starving Igbos gained global sympathy.

Media campaigns about the Biafrans grew in summer 1968. The killings and famine were called genocide. They were compared to The Holocaust. Igbo refugee camps were compared to Nazi camps.

In the UK, aid appeals talked about imperial responsibility. In Ireland, appeals used shared Catholicism and civil war experiences. These appeals used old cultural values to support new international NGOs. Irish public opinion strongly supported Biafra. Most Catholic priests in Biafra were Irish. They sympathized with Biafrans. The threat of famine and the fight for independence deeply affected Irish people. They saw parallels with their own history.

In Israel, the Holocaust comparison was used. The idea of a threat from hostile Muslim neighbors was also promoted.

The Biafran war showed Westerners images of starving African children. It was one of the first African disasters widely covered by TV. The televised disaster and the growing NGOs helped each other. NGOs had their own communication networks. They played a big role in shaping news coverage.

Biafran leaders studied Western propaganda. They released carefully planned public messages. They wanted to appeal to international opinion. They also wanted to keep morale high at home. Cartoons were used to show simple interpretations of the war. Novelist Chinua Achebe became a strong supporter of Biafra.

On May 29, 1969, Bruce Mayrock, a student, set himself on fire at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. He was protesting what he saw as genocide against Biafra. He died the next day. On November 25, 1969, musician John Lennon returned his MBE award. He protested British support for Nigeria.

Kwale Oilfield Incident

In May 1969, Biafran commandos attacked an oil field in Kwale. They killed 11 workers and technicians. They captured three Europeans unharmed. At a nearby field, they captured 15 more foreign workers. These included 14 Italians, 3 West Germans, and one Lebanese. It was claimed these foreigners were fighting with Nigerians. They were tried by a Biafran court and sentenced to death.

This caused an international outcry. The Pope, and the governments of Italy, the UK, and the US pressured Biafra. On June 4, 1969, Ojukwu pardoned the foreigners. They were released to special envoys from Ivory Coast and Gabon.

The War Ends

With more British support, Nigerian forces launched their final attack on Biafra on December 23, 1969. The 3rd Marine Commando Division led this attack. It was commanded by Col. Olusegun Obasanjo, who later became president. This attack split Biafra into two by the end of the year.

The final Nigerian attack, "Operation Tail-Wind," began on January 7, 1970. The 3rd Marine Commando Division attacked. The 1st Infantry division attacked from the north. The 2nd Infantry division attacked from the south. The Biafran towns of Owerri fell on January 9. Uli fell on January 11.

A few days earlier, Ojukwu fled by plane to the Ivory Coast. He left his deputy, Philip Effiong, to surrender. Effiong surrendered to General Yakubu Gowon of the Nigerian Army on January 13, 1970. The surrender paper was signed on January 14, 1970, in Lagos. This ended the civil war and Biafra's attempt to break away. Fighting stopped a few days later. Nigerian forces advanced into the remaining Biafran areas with little resistance.

After the war, Gowon said, "The tragic chapter of violence is just ended. We are at the dawn of national reconciliation. Once again we have an opportunity to build a new nation."

After the War: Legacy

Impact on the Igbo People

The war greatly harmed the Igbo people. Many lives were lost. Money and buildings were destroyed. It is estimated that up to one million people died. Most died from hunger and disease caused by Nigerian forces. More than half a million people died from the deliberate blockade. Thousands died every day as the war went on. The Red Cross estimated 8,000 to 10,000 deaths from starvation each day in September 1968.

A Nigerian peace conference delegate said in 1968 that "starvation is a legitimate weapon of war." This generally reflects the Nigerian government's policy. The Nigerian army is also accused of other terrible acts. These include bombing civilians and mass killings.

The first feelings of Igbo nationalism began right after the war.

Minority Groups in Biafra

Ethnic minorities like the Ibibio, Ijaw, and Ogoni made up about 40% of Biafra's population. At first, their feelings about the war were mixed. They had suffered like the Igbos in the North. But Biafran authorities seemed to favor the Igbo majority. This made minorities feel negative. People suspected of not supporting Biafra were called 'sabo.' This was a feared label. It often led to death by Biafran forces or angry mobs.

Minorities in Biafra suffered from both sides. The attacks in the North in 1966 targeted all people from Eastern Nigeria. But tensions grew as minorities were suspected of helping Nigerian troops. Nigerian troops also committed terrible acts. In the Rivers area, hundreds of minorities who supported Biafra were killed by Nigerian troops. In Calabar, about 2,000 Efiks were also killed by Nigerian troops.

Was it Genocide?

Some experts, like legal scholar Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe, argue the Biafran war was a genocide. They say no one has been held responsible. Others agree that starvation was used on purpose. But they say it was not genocide because the Igbo were not wiped out after the war. They also say Nigeria was fighting to keep control, not to destroy the Igbo.

Biafra complained of genocide to an international group of lawyers. This group concluded that Nigeria's actions against the Igbo were genocide. A jurist called the Asaba Massacre "the first black-on-black genocide." Ekwe-Ekwe blames the British government for supporting Nigeria. He says this allowed the harm against the Igbo to continue.

Rebuilding Nigeria

Rebuilding after the war was fast, thanks to oil money. But the old ethnic and religious tensions remained. Some accused Nigerian officials of taking money meant for rebuilding Biafran areas. Military rule continued in Nigeria for many years. People in oil-producing areas said they were not getting a fair share of oil money.

Laws were made to stop political parties from being based on ethnicity. But this has been hard to do. Igbos who fled the war found their jobs taken. The government did not give them back. They said the Igbos had "resigned." This also happened with Igbo-owned properties. People from other regions took over Igbo houses. The government called these properties "abandoned." This made Igbos feel unfairly treated.

Nigeria also changed its currency. Old Nigerian money held by Biafrans was no longer valid. After the war, people from the East only received £20, no matter how much money they had. This was seen as a way to keep the Igbo middle class from getting rich again.

Biafra's Return Attempts

On May 29, 2000, The Guardian reported that President Olusegun Obasanjo changed the dismissal of all military people who fought for Biafra. He said it was based on the idea that "justice must at all times be tempered with mercy."

Biafra was mostly forgotten until new groups tried to bring it back. The Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra is one such group. Chinua Achebe's last book, There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra, also restarted discussions about the war. In 2012, the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) separatist movement was founded. It is led by Nnamdi Kanu. In 2021, tensions between IPOB and Nigeria grew into the violent Orlu Crisis. IPOB declared that the "second Nigeria/Biafra war" had begun. They vowed that this time, Biafra would win.

Long-Term Effects on Generations

A 2021 study looked at the effects of the war. It found that women who experienced the war were shorter as adults. They were also more likely to be overweight. They had their first child earlier and had less education. If mothers experienced the war, their children were less likely to survive. They also had poorer growth and less education. The effects varied based on how old someone was during the war.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra civil de Nigeria para niños

In Spanish: Guerra civil de Nigeria para niños

- List of civil wars

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |