Dean Rusk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dean Rusk

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 54th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office January 21, 1961 – January 20, 1969 |

|

| President | John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Christian Herter |

| Succeeded by | William P. Rogers |

| 2nd Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs | |

| In office March 28, 1950 – December 9, 1951 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | William Walton Butterworth |

| Succeeded by | John Moore Allison |

| 1st Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs | |

| In office February 9, 1949 – May 26, 1949 |

|

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Dean Acheson (Congressional Relations and International Conferences) |

| Succeeded by | John D. Hickerson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

David Dean Rusk

February 9, 1909 Cherokee County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | December 20, 1994 (aged 85) Athens, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Virginia Foisie

(m. 1937) |

| Children | 3, including Peggy, David and Richard |

| Education | Davidson College (BA) St John's College, Oxford (BS, MA) University of California, Berkeley (LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Legion of Merit |

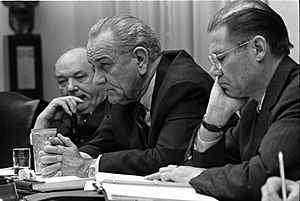

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909 – December 20, 1994) was a very important American leader. He served as the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969. This means he was the main person in charge of America's relationships with other countries. He worked under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He was the second-longest serving Secretary of State ever!

Before this big job, Rusk was a high-ranking government official in the 1940s and early 1950s. He also led a major charity organization. He is known for helping to divide Korea into two countries (North and South Korea) at the 38th parallel north after World War II.

Rusk grew up in a poor farming family in Cherokee County, Georgia. He earned scholarships to go to Davidson College and then to University of Oxford in England. He later taught at Mills College in California. During World War II, he became an army officer and served in Asia. After the war, he worked for the United States Department of State, moving up to important roles. In 1952, he became the president of the Rockefeller Foundation, a large charity group.

When John F. Kennedy became president in 1960, he asked Rusk to be his Secretary of State. Rusk was a quiet advisor to Kennedy. He helped during the Cuban Missile Crisis, a very tense time when the U.S. and the Soviet Union almost went to war. Even though he had some doubts at first, Rusk became a strong supporter of America's involvement in the Vietnam War. After Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, President Lyndon Johnson asked Rusk to stay on, and Rusk became one of Johnson's favorite advisors. After leaving his role in 1969, Rusk taught about international relations at the University of Georgia School of Law.

Contents

- Growing Up and School

- Early Career Before 1961

- Secretary of State

- How He Was Chosen

- Vietnam and Laos

- Military Plans and Cuba

- Overthrow of Vietnam President Diem

- Relationship with President Kennedy

- Defending South Vietnam

- Distrusting Robert Kennedy

- Vietnam in 1964

- Relations with Egypt's Nasser

- Robert Kennedy Undercuts Rusk

- Vietnam in 1965

- Britain Refuses Troops

- Discussing a Bombing Pause

- France Leaves NATO Command

- Fulbright Hearings on Vietnam

- Hawks vs. Doves in 1966

- De-escalation in 1967

- Rusk's Family Life

- Rusk and the Peace Movement

- Vietnam and the 1968 Election

- End of His Term

- Life After Office

- What People Remember About Dean Rusk

- Images for kids

- See also

Growing Up and School

David Dean Rusk was born in a countryside area of Cherokee County, Georgia. His family had moved to America from Northern Ireland around 1795. His father, Robert Hugh Rusk, was a cotton farmer and school teacher. His mother, Elizabeth Frances Clotfelter, was also a teacher. When Dean was four, his family moved to Atlanta, where his father worked for the U.S. Post Office. Rusk learned to value hard work and good behavior from his family.

His family supported the Democratic Party, like most white Southerners at the time. Young Rusk looked up to President Woodrow Wilson. Growing up poor made him understand the struggles of African Americans. When he was nine, Rusk heard President Wilson speak about the League of Nations, an organization to help countries work together for peace. Rusk also grew up hearing stories about the "Lost Cause" from the American Civil War. He believed that young men should be ready to serve their country. At age 12, he joined the ROTC, which trains students for military service. He always respected military leaders and often followed their advice later in life.

Rusk went to public schools in Atlanta and graduated from Boys High School in 1925. He worked for a lawyer for two years before going to Davidson College, a Presbyterian school in North Carolina. He worked hard and was a top student, graduating in 1931. He also joined a military honor society.

Rusk won a Rhodes Scholarship to study at University of Oxford in England. There, he learned about international relations and earned a master's degree. He loved learning about English history and culture and made many friends among important British people. Rusk's journey from poverty to success made him a strong believer in the "American Dream". He felt that anyone, no matter their background, could achieve great things in America.

Rusk married Virginia Foisie on June 9, 1937. They had three children: David, Richard, and Peggy Rusk.

From 1934 to 1949, Rusk taught at Mills College in Oakland, California. He also earned a law degree from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law in 1940.

Early Career Before 1961

While studying in England, Dean Rusk won the Cecil Peace Prize in 1933. His experiences in the 1930s greatly shaped his future ideas.

Military Service in Asia

Rusk was part of the Army reserves in the 1930s. He was called to active duty in December 1940 as a captain. He worked as a staff officer in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. By the end of the war, he was a colonel and received the Legion of Merit award.

Working for the State Department (1945-1953)

After the war, Rusk briefly worked for the United States Department of War. In February 1945, he joined the United States Department of State, which handles foreign policy. He worked on issues related to the United Nations. That same year, he suggested dividing Korea into American and Soviet areas of influence at the 38th parallel.

Rusk supported the Marshall Plan, which helped rebuild Europe after the war, and the United Nations. In 1948, he advised President Truman not to recognize Israel as a new country, fearing it would upset oil-rich Arab nations. However, Truman decided to recognize Israel anyway. Rusk respected this decision, believing that the president makes the final foreign policy choices. In 1949, he became a deputy to Dean Acheson, who was then the Secretary of State.

Assistant Secretary for Asian Affairs

In 1950, Rusk asked to become the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs because he felt he knew Asia best. He played a key role in the U.S. decision to get involved in the Korean War. He also helped with Japan's payments to countries that won the war. Rusk was a careful diplomat who always looked for international support. He believed the U.S. should support Asian countries that wanted to be independent from European rule.

Supporting France in Indochina

When the question came up about whether the U.S. should help France keep control of Indochina (which included Vietnam) against the Communist Viet Minh fighters, Rusk argued for supporting France. He said the Viet Minh were just tools of Soviet expansion in Asia. Under pressure from the U.S., France gave some independence to the State of Vietnam in 1950. However, many knew it was still largely controlled by France. Rusk believed that supporting France was necessary to stop communism.

The Korean War

In April 1951, President Truman removed General Douglas MacArthur from his command in Korea. This happened because MacArthur wanted to expand the war into China, but Truman did not. In May 1951, Rusk gave a speech where he suggested that the U.S. should unite Korea under Syngman Rhee and even try to overthrow Mao Zedong in China. This speech caused a stir and embarrassed Secretary Acheson. Because of this, Rusk had to leave his government job.

Leading the Rockefeller Foundation

After leaving the State Department, Rusk and his family moved to Scarsdale, New York. He became a trustee for the Rockefeller Foundation from 1950 to 1961. In 1952, he became the president of this important foundation.

Secretary of State

How He Was Chosen

On December 12, 1960, the new President-elect, John F. Kennedy, chose Dean Rusk to be his Secretary of State. Rusk wasn't Kennedy's first choice, but Kennedy was interested in an article Rusk had written. In it, Rusk said the president should lead foreign policy, with the Secretary of State as an advisor. Rusk wasn't very keen on the job because it paid less than his role at the Rockefeller Foundation. But he agreed to take it out of a strong sense of duty to his country.

Kennedy often called Rusk "Mr. Rusk" instead of Dean.

Rusk took charge of a department he knew well. He believed in using military action to fight communism. Even though he had private doubts about the Bay of Pigs Invasion (a failed attempt to overthrow Cuba's government), he didn't openly oppose it. Early in his time as Secretary, he had doubts about the U.S. getting more involved in Vietnam. But later, he became a strong public supporter of U.S. actions in the Vietnam War. This made him a target of anti-war protests. Rusk often sided with Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in supporting a strong approach to Vietnam.

Vietnam and Laos

In March 1961, the Communist Pathet Lao group won a big battle in Laos. Rusk was frustrated that neither side in the Lao civil war seemed to fight very hard. He doubted that bombing alone would stop the Pathet Lao, believing that ground troops were also needed.

Military Plans and Cuba

In April 1961, Rusk supported sending more American military advisors to South Vietnam, even though it went against the 1954 Geneva Accords (agreements that limited foreign military presence). Rusk suggested keeping this deployment a secret. He also favored a strong stance on Laos, but Kennedy decided against it due to the risk of Chinese involvement. Rusk also supported helping developing countries and promoting international trade.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Rusk supported using diplomacy to solve the problem. Some historians believe his advice helped prevent a nuclear war.

Overthrow of Vietnam President Diem

In August 1963, there was a lot of confusion in the Kennedy administration. A plan to remove President Diem of South Vietnam was discussed. Rusk cautiously approved it, thinking Kennedy had already agreed. When it turned out Kennedy hadn't, a tense meeting happened. Rusk remained silent, not taking a side. Kennedy was very frustrated. Rusk later said that the U.S. would not leave Vietnam "until the war is won."

Relationship with President Kennedy

In his autobiography, Rusk said he didn't have a great relationship with President Kennedy. Kennedy often found Rusk too quiet and felt the State Department didn't come up with new ideas. Some believed that Kennedy acted as his own Secretary of State. Rusk offered to resign many times, but Kennedy never accepted. Rumors of Rusk being replaced were common. After Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Rusk offered his resignation to the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson. However, Johnson liked Rusk and asked him to stay, which he did for the rest of Johnson's presidency.

Defending South Vietnam

In June 1964, Rusk met with the French ambassador to discuss a plan to make both North and South Vietnam neutral. Rusk was doubtful about this plan. He told the ambassador that defending South Vietnam was as important as defending Berlin. He believed that losing South Vietnam would weaken the fight against communism everywhere.

Distrusting Robert Kennedy

Rusk quickly became one of President Johnson's favorite advisors. Johnson and Rusk both felt that Robert F. Kennedy, who wanted to be Johnson's running mate, was overly ambitious.

Vietnam in 1964

After the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Rusk supported the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave the president more power to act in Vietnam. In August 1964, Rusk asked for support from both political parties for U.S. foreign policy. He criticized Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater for his comments.

In September 1964, Johnson met with his national security team to decide what to do about Vietnam. Rusk advised caution, saying military action should only happen after diplomacy had failed. Rusk was frustrated with the constant fighting among South Vietnam's military leaders. He told the U.S. ambassador to make it clear that the U.S. was tired of their disagreements. Rusk felt that Americans needed to get more involved in South Vietnam's affairs to make things better. He also said the U.S. would not be pushed out of the Gulf of Tonkin.

A peace effort was started by the UN Secretary General U Thant in September 1964. The Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, even pressured North Vietnam to take part. Rusk did not push this idea with Johnson, saying that joining the talks would look like accepting aggression. The peace effort ended when Khrushchev was removed from power.

On November 1, 1964, the Viet Cong attacked an American airbase, killing four Americans. Rusk told the ambassador that Johnson didn't want to act before the election, but after the election, there would be "a more systematic campaign of military pressure on the North."

Relations with Egypt's Nasser

In December 1964, Egypt's President Nasser gave a strong anti-American speech. Johnson was very angry. Rusk later recalled Nasser's defiant words. In January 1965, Johnson stopped all food aid to Egypt, which caused an economic crisis there. Nasser tried to get the aid back but failed. Instead of changing his policies, Nasser turned to the Soviet Union for support.

Robert Kennedy Undercuts Rusk

In April 1965, Senator Robert Kennedy suggested to President Johnson that he should fire Rusk and replace him. Johnson was surprised and refused, saying he liked Rusk.

Vietnam in 1965

In May 1965, Rusk told Johnson that North Vietnam's peace terms were misleading. In June 1965, when General William Westmoreland asked for 180,000 more troops for Vietnam, Rusk argued that the U.S. had to fight to keep its promises around the world. He also wondered if Westmoreland was exaggerating the problems to get more troops. However, Rusk warned the president that if South Vietnam was lost, it would lead to "our ruin and almost certainly to a catastrophic war." He also said the U.S. should have sent more troops in 1961.

Rusk disagreed with his Undersecretary of State, George Ball, about Vietnam. Ball felt the South Vietnamese leaders were not worth supporting, but Rusk believed they would find a way to succeed. Rusk thought Ball's ideas about reducing American involvement should be kept secret.

Britain Refuses Troops

In 1964 and 1965, Rusk asked British Prime Minister Harold Wilson to send British troops to Vietnam, but the requests were refused.

Discussing a Bombing Pause

In December 1965, when Defense Secretary McNamara suggested pausing the bombing of North Vietnam, Rusk said there was only a small chance it would lead to peace talks. However, he still argued for the pause to show the American people that all options were being tried. When Johnson announced the bombing pause, Rusk told the press, "We have put everything into the basket of peace except the surrender of South Vietnam." The North Vietnamese refused to talk peace until the bombing stopped "unconditionally and for good." They saw the bombing as a major attack on their country's independence. In January 1966, Johnson ordered the bombing to restart.

France Leaves NATO Command

President of France Charles de Gaulle pulled France out of NATO's military command in February 1966 and told all American military forces to leave France. President Johnson asked Rusk to clarify if even the bodies of buried American soldiers had to leave. Rusk wrote in his autobiography that de Gaulle never answered.

Fulbright Hearings on Vietnam

In February 1966, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee held hearings on the Vietnam War. They invited experts who criticized the war. Rusk, as Johnson's main spokesperson, testified to defend the war. He said it was a morally right fight to stop the spread of communism. These televised hearings were like a "political theater," with Rusk and Senator Fulbright debating the war.

Hawks vs. Doves in 1966

By 1966, Johnson's administration was split between "hawks" (who wanted to fight harder) and "doves" (who wanted peace talks). Rusk, along with General Earle Wheeler and Walt Whitman Rostow, were the main "hawks." McNamara, Rusk's former ally, became a leading "dove." Rusk saw leaving Vietnam as giving in to the enemy.

De-escalation in 1967

On April 18, 1967, Rusk said the U.S. was ready to reduce the conflict if North Vietnam took similar steps.

In 1967, Rusk opposed a peace plan suggested by Henry Kissinger. When Kissinger reported that North Vietnam would only talk peace if the bombing stopped first, Rusk argued for continuing the bombing.

Rusk's Family Life

Rusk's strong support for the Vietnam War caused pain for his son Richard, who was against the war. This led to a difficult time between father and son.

In 1967, Rusk thought about resigning because his daughter, Peggy, planned to marry a classmate. This marriage caused some controversy, with one newspaper saying it was "offensive." However, after talking to McNamara and the president, Rusk decided not to resign. A year after his daughter's wedding, Rusk was invited to teach at the University of Georgia Law School. Some people tried to block his appointment because of his daughter's marriage, but the university still hired him.

Rusk and the Peace Movement

In October 1967, Rusk believed that the anti-war protests were influenced by "Communists." He asked Johnson to investigate, but the investigation found no strong evidence of Communist control over the U.S. peace movement. Rusk said the report was "naive."

Vietnam and the 1968 Election

When Johnson first considered not running for president in 1968, Rusk opposed it. He said Johnson was the Commander-in-Chief during a war and leaving would hurt the country. When McNamara suggested stopping the bombing to start peace talks, Rusk disagreed, saying it would remove the "incentive for peace."

On January 5, 1968, Rusk sent notes to the Soviet ambassador, asking for help to avoid future bombings of Russian cargo ships in North Vietnam. On February 9, Rusk was asked about reports of U.S. nuclear weapons in South Vietnam.

On April 17, Rusk admitted that the U.S. had faced some challenges in the war but should keep trying to find a neutral place for peace talks. The next day, he suggested more locations, accusing North Vietnam of playing propaganda games.

Before peace talks began in Paris in May 1968, Rusk wanted to bomb North Vietnam more. However, Defense Secretary Clark Clifford strongly opposed this, saying it would ruin the talks. Clifford convinced Johnson not to do it. Rusk still believed bombing gave the U.S. an advantage in the talks. When Richard Nixon asked where the war was lost, Rusk replied, "In the editorial rooms of this country," suggesting the media's negative coverage was to blame.

On June 26, Rusk promised Berlin citizens that the U.S. and its allies would protect their freedom. He criticized East Germany's travel restrictions.

On September 30, Rusk met with Israel's Foreign Minister to discuss peace plans for the Middle East.

In October 1968, Rusk opposed Johnson's idea of a complete bombing halt in North Vietnam. On November 1, Rusk said that North Vietnam's allies should pressure them to speed up peace talks in Paris.

End of His Term

Richard Nixon won the election, and Rusk prepared to leave office on January 20, 1969. On December 1, 1968, Rusk said the Soviet Union needed to help move peace talks forward in Southeast Asia. On December 22, Rusk appeared on TV to confirm that 82 crew members of the USS Pueblo spy ship were safe.

In Johnson's last days as president, he wanted to nominate Rusk to the Supreme Court. Even though Rusk had studied law, he didn't have a law degree or practice law. Johnson said the Constitution didn't require it. However, Senator James Eastland, a powerful senator, said he would not approve Rusk. Eastland was a supporter of segregation and had not forgiven Rusk for his daughter's marriage.

On January 2, 1969, Rusk met with Jewish American leaders to assure them that the U.S. still supported Israel.

Life After Office

January 20, 1969, was Rusk's last day as Secretary of State. He left quietly, saying, "Eight years ago, Mrs. Rusk and I came quietly. We wish now to leave quietly. Thank you very much." After a farewell dinner, Rusk drove away in an old car, which seemed to symbolize the end of the Johnson administration. When he returned to Georgia, Rusk felt very sad and had physical pains that doctors couldn't explain. He couldn't work for a while, and the Rockefeller Foundation paid him a salary.

On July 27, 1969, Rusk supported the Nixon administration's plan for an anti-missile system. That same year, Rusk received two important awards: the Sylvanus Thayer Award and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After retiring, he taught international law at the University of Georgia School of Law from 1970 to 1984. Rusk was very tired after eight years as Secretary of State. Some people tried to block his teaching job because of his daughter's marriage, but they failed. Rusk found teaching very fulfilling. He told his son that his students helped him feel young again and start a new life after his difficult years in Washington.

In the 1970s, Rusk was part of a group that was against reducing tensions with the Soviet Union and didn't trust nuclear arms control treaties.

In 1973, Rusk gave a speech honoring President Johnson after he passed away.

In 1984, Rusk's son Richard, who he hadn't spoken to since 1970 because of their different views on the Vietnam War, came back to Georgia to make up with his father. As part of their reconciliation, Rusk, who was blind by then, dictated his memories to his son. These memories became the book As I Saw It.

Rusk's Memoir

In his book As I Saw It, Rusk didn't show much anger towards other officials he had disagreed with, but he was very critical of Robert Kennedy and the UN Secretary General U Thant. Rusk also expressed anger at how the media covered the Vietnam War, saying that anti-war journalists "faked" stories. He believed that if there was true freedom of the press, newspapers would have shown the war more positively. Despite his strong views against the Soviet Union, Rusk said that during his time as Secretary of State, he never saw any proof that the Soviet Union planned to invade Western Europe. He also said he "seriously doubted" they ever would. Historians noted that Rusk was much warmer and more protective towards President Johnson than he was towards Kennedy.

Historian George C. Herring wrote that Rusk's book was mostly uninteresting when it came to his time as Secretary of State. However, the most interesting parts were about his youth in the South and his conflict and reconciliation with his son Richard.

Dean Rusk passed away from heart failure in Athens, Georgia, on December 20, 1994, at age 85. He and his wife are buried in Athens.

Several places are named in his honor, including Rusk Eating House and the Dean Rusk International Studies Program at Davidson College. Dean Rusk Middle School in Canton, Georgia, and Dean Rusk Hall at the University of Georgia are also named after him.

What People Remember About Dean Rusk

Historians generally agree that Rusk was a very smart man. However, he was also very shy and focused on details, which sometimes made him slow to make decisions or explain government policies clearly to the media. He was deeply involved in major events like the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Vietnam War.

Regarding Vietnam, historians say that President Johnson relied heavily on Rusk's advice. Rusk, along with Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and national security advisor McGeorge Bundy, believed that a Communist takeover of all of Vietnam was unacceptable. They thought the only way to stop it was for America to get more involved. Johnson followed their advice and ignored other opinions.

Rusk's son, Richard, wrote about his father's time as Secretary of State. He felt that his father's quiet and reserved nature made it hard for him to truly rethink the Vietnam policy. He believed that his father, despite being trained for high office, was not ready to admit that thousands of American and Vietnamese lives might have been lost for nothing.

Historian George Herring described Rusk in 1992 as a "thoroughly decent individual, a man of stern countenance and unbending principles." He was also very private and quiet. Herring called him the "perfect number two," meaning he was a loyal helper who might have had private doubts but would always defend the president's decisions.

In summary, many believe Rusk was a good, smart, and experienced man who had a lot going for him. But as Secretary of State, he seemed to hold back from leading and acted more like a loyal follower of the presidents rather than a strong, persuasive advisor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dean Rusk para niños

In Spanish: Dean Rusk para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |