Gulf of Tonkin Resolution facts for kids

|

|

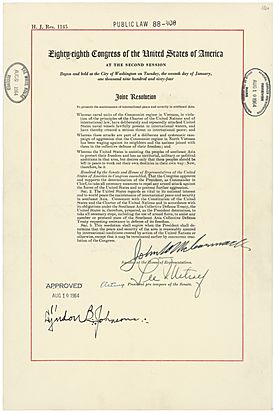

| Long title | A joint resolution "To promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia." |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Southeast Asia Resolution |

| Enacted by | the 88th United States Congress |

| Effective | August 10, 1964 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 88-408 |

| Statutes at Large | 78 Stat. 384 |

| Legislative history | |

|

|

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, also known as the Southeast Asia Resolution, was a special agreement passed by the United States Congress on August 7, 1964. It was a direct response to events that happened in the Gulf of Tonkin.

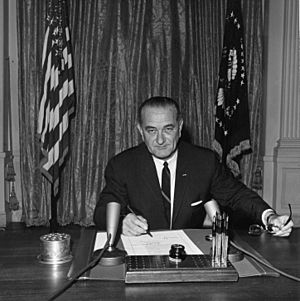

This resolution was very important because it gave U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson the power to use military force in Southeast Asia. He could do this without Congress formally declaring war. The resolution allowed the president to do whatever was needed to help any country that was part of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty. This included sending in armed forces.

Only two senators, Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening, voted against it. Senator Gruening felt that American soldiers should not be sent to fight in a war that was not America's business. The Johnson administration later used this resolution to greatly increase U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam. This led to open warfare between North Vietnam and the United States.

Contents

Why the U.S. Got Involved

In the mid-1950s, a communist uprising began in South Vietnam against its government. North Vietnamese forces also started using the Ho Chi Minh trail through Laos to support rebels in the south. By 1960, a large part of South Vietnam was under communist control. Between 1961 and 1963, about 40,000 communist soldiers moved from North Vietnam into the south.

By 1963, the U.S. government was worried that South Vietnam was losing the war. These worries grew after South Vietnam's leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, was overthrown and killed in November 1963. The U.S. Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, reported that the situation was "very disturbing." He said the Viet Cong (communist fighters) were winning.

American military leaders believed that if South Vietnam fell to communism, it would be a huge blow to the U.S. They thought it would make America look weak. This idea was called the "domino theory." It suggested that if one country fell to communism, others nearby would follow like dominoes.

President Johnson wanted to focus on problems at home, like civil rights. But he was afraid that "losing" South Vietnam would make him seem "soft on Communism." This was a serious accusation for any American politician at the time. Johnson told his military leaders that once he was elected president, they could "have their war."

Secret Operations and the Need for a Resolution

The U.S. had been secretly trying to weaken North Vietnam. Since 1961, the CIA had trained South Vietnamese commandos. These teams were sent into North Vietnam to try and start an anti-communist rebellion. However, these missions were not successful, and many agents were captured.

In January 1964, President Johnson approved a plan to increase these secret operations against North Vietnam. This plan was called Operation 34A. As part of this, South Vietnamese commandos began raiding North Vietnam's coast in February 1964.

By early 1964, many U.S. experts believed that South Vietnam would likely fall without American military help. However, under the U.S. Constitution, only Congress can declare war. President Johnson did not want a full declaration of war. He feared it would lead to a large-scale invasion of North Vietnam. He also worried that invading North Vietnam might cause China to join the war, like they did in the Korean War.

To solve this problem, Johnson's advisors suggested that Congress pass a resolution. This resolution would give the president the power to use military force in Vietnam. This was similar to a resolution passed in 1955 that gave President Eisenhower power to protect Taiwan.

Some senators, like Mike Mansfield and Wayne Morse, were against the U.S. getting more involved in Vietnam. Senator Morse strongly believed that only Congress should have the power to declare war. He worried that such a resolution would weaken Congress's power.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident

In the early 1960s, North Vietnam grew closer to China, which was more aggressive than the Soviet Union. To regain influence, the Soviet Union sold North Vietnam advanced radar systems and missiles. The U.S. Navy needed information about these new radar systems. So, they increased their DESOTO patrols off the coast of North Vietnam. These patrols involved U.S. destroyers collecting electronic information.

The U.S. Navy also used South Vietnamese commandos to attack North Vietnamese radar stations. The idea was to force the North Vietnamese to turn on their radars. This would allow the American ships to learn what frequencies they used.

By July 1964, the North Vietnamese coast was a war zone. South Vietnamese commandos were constantly raiding the area. An American destroyer, the USS Maddox, was sent to the Gulf of Tonkin. Its job was to collect electronic information on the North Vietnamese radar system. The Maddox was ordered to stay at least 8 miles from the North Vietnamese coast. North Vietnam claimed control of waters up to 12 miles from its coast, but the U.S. did not recognize this claim.

On July 30, 1964, South Vietnamese commandos tried to attack a North Vietnamese radar station. They were detected and could not land. The radar on the island was turned on, and the Maddox picked up its frequency. North Vietnam protested this raid.

On August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox reported being attacked by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats. The Maddox fired back, and the torpedo boats launched their torpedoes, but all missed. Four U.S. Navy jet fighters then attacked the torpedo boats, damaging all three.

President Johnson was told about the incident. He called the Soviet Union to say the U.S. did not want war. But he hoped the Soviets would tell North Vietnam not to attack American warships. Johnson did not use this first attack as a reason to ask Congress for a resolution. He wanted an incident where North Vietnam was clearly the aggressor.

To try and provoke such an incident, Johnson ordered the Maddox to continue patrolling. Another destroyer, the USS Turner Joy, joined it. They were ordered to sail 8 miles from North Vietnam, in waters the U.S. considered international.

Two days later, on a stormy night, August 4, 1964, both the Maddox and the Turner Joy reported being attacked again by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Aircraft from the USS Ticonderoga were launched, but the pilots saw no enemy ships. Hanoi later said it had not launched a second attack. The captain of the Maddox soon doubted if a second attack had actually happened. He thought the "torpedo boats" might have been radar signals caused by the storm. He noted that no sailor on either ship had seen a torpedo boat or heard gunfire other than their own.

A later investigation by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee found that the Maddox was on an electronic intelligence mission. It also learned that U.S. Navy communications had questioned whether the second attack occurred. In 2005, a declassified study concluded that the Maddox was attacked on August 2, but there might not have been any North Vietnamese ships present on August 4.

Congress Votes on the Resolution

Early on August 4, 1964, President Johnson told several members of Congress that North Vietnam had attacked an American patrol. He promised to strike back and asked Congress to support a resolution. Johnson felt he was being "tested" by North Vietnam. He worried that if he seemed indecisive, his political opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater, might gain support.

Johnson told his Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, to make sure the naval report confirmed the attack. Admiral Sharp, a military leader, put pressure on the Maddox's captain to confirm the attack. The captain later sent a message saying the "original ambush was bona fide."

The CIA director, John A. McCone, believed North Vietnam did not want war. He thought they were acting out of "pride" because American warships were sailing in waters they claimed. However, McCone still supported bombing raids.

Johnson invited 18 senators and congressmen to the White House. He told them he had ordered bombing raids on North Vietnam and asked for their support for a resolution. The atmosphere made it hard for them to oppose him. Most supported him, though Senator Mansfield still thought the matter should go to the United Nations. Johnson said the UN was not an option.

Within hours, President Johnson ordered air strikes on North Vietnamese torpedo boat bases. He announced on television that U.S. naval forces had been attacked. He asked for approval of a resolution to show that the U.S. was united in protecting peace in Southeast Asia. The media largely supported Johnson's actions.

On August 5, 1964, Johnson sent the resolution to Congress. It would give him the power to "take all necessary steps" and "prevent further aggression." Johnson privately believed the second incident had not happened. He wanted the resolution to pass with strong support to show North Vietnam that Congress was united.

Robert McNamara testified before Congress. He said the Maddox was on a "routine mission" and denied any connection to South Vietnamese raids. Senator Wayne Morse asked about a connection to Operation 34A, but McNamara denied it. However, the administration did not reveal that the island raids were part of a secret program of attacks on North Vietnamese sites.

Despite McNamara's statements, Senator Morse argued that the conflict should be settled through talks, not fighting. He was supported only by Senator Ernest Gruening. Senator Richard Russell Jr., who had doubts about Vietnam, supported the resolution, saying, "Our national honor is at stake."

Senator J. William Fulbright, a respected foreign policy expert, also spoke in favor of the resolution. He called North Vietnam's actions "aggression" and praised Johnson's "great restraint." Fulbright believed the resolution would intimidate North Vietnam and prevent a larger war. He persuaded other senators to support it, telling them it was "harmless" and meant to prevent war.

After less than nine hours of debate, Congress voted on August 10, 1964. The House of Representatives voted 416–0 in favor. The Senate approved it by a vote of 88–2. Senators Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening cast the only "no" votes. Senator Morse warned that it was a "historic mistake" and that those who voted for it would "live to regret it."

Using the Resolution as a Policy Tool

The resolution's passage worried some U.S. allies, like Canada. A Canadian diplomat tried to carry messages between Hanoi and Washington to stop the war from growing. He told North Vietnam's Premier that Johnson was serious about using his new powers. He also said Johnson would offer benefits if North Vietnam stopped trying to overthrow South Vietnam's government. North Vietnam rejected the offer.

Even with the power to wage war, Johnson was slow to use it. He hoped his ambassador could pressure South Vietnam to fight better. Military leaders, however, pushed for immediate bombing campaigns against North Vietnam.

In November 1964, Viet Cong guerrillas attacked an American air field, killing American servicemen. Military leaders again recommended bombing North Vietnam. Johnson hesitated, creating a "working group" to consider options. He eventually approved some bombing raids and more secret operations.

In February 1965, after another Viet Cong attack, Johnson decided it was time for a bombing campaign. Only Senator Mansfield and Vice President Hubert Humphrey opposed the plan.

Johnson ordered Operation Flaming Dart on February 7, 1965. This bombing raid on a North Vietnamese Army base marked the start of more intense bombing. On March 2, 1965, Johnson ordered Operation Rolling Thunder, a major bombing campaign against North Vietnam. On March 8, 1965, two battalions of U.S. Marines landed in Danang to protect the air base. This marked the beginning of a larger U.S. ground presence in Vietnam.

Fulbright, who had supported the resolution, now warned Johnson that a "massive ground and air war" would be a "disaster." But Johnson had the legal power to wage war and ignored the warning. The Joint Chiefs of Staff recommended sending more troops. By April 1965, Johnson approved sending 40,000 U.S. Army troops to South Vietnam. By July, he approved a request for 180,000 more troops.

In a recorded phone call, Johnson admitted that when they asked for the resolution, they had no intention of sending so many ground troops. On July 28, 1965, Johnson announced on TV that the U.S. would meet the military's needs and "will stand in Vietnam."

In February 1966, Senator Morse tried to repeal the resolution. He argued it was unconstitutional and used in ways Johnson had promised it would not be. Most senators, however, felt it was their patriotic duty to support the president during wartime. Only five senators voted for Morse's motion.

Repealing the Resolution

By 1967, the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was very costly. Many people opposed the war, and a movement began to repeal the resolution. Critics called it a "blank check" that gave the president too much power.

The administration of President Richard Nixon, who took office in 1969, at first opposed repealing the resolution. But in 1970, they changed their stance. They said their actions in Southeast Asia were based on the president's power as commander-in-chief, not just the resolution. The U.S. had also begun withdrawing its forces from Vietnam in 1969, a policy called "Vietnamization."

Growing public opposition to the war eventually led to the resolution's repeal. It was added to the Foreign Military Sales Act of 1971, which Nixon signed in January 1971. To limit the president's power to send U.S. forces into conflict without a formal declaration of war, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution in 1973. This was passed over Nixon's veto. The War Powers Resolution is still in effect today. It requires the president to consult with Congress before engaging U.S. forces in hostilities.

See also

In Spanish: Resolución del Golfo de Tonkin para niños

In Spanish: Resolución del Golfo de Tonkin para niños

- Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |