Chinua Achebe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Chinua Achebe

|

|

|---|---|

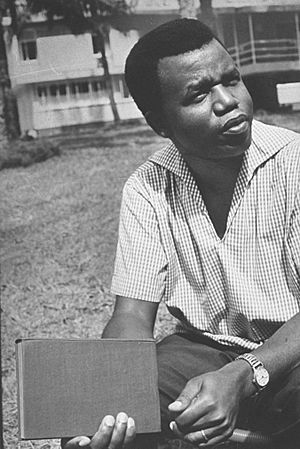

Achebe in Lagos, 1966

|

|

| Born | Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe 16 November 1930 Ogidi, British Nigeria |

| Died | 21 March 2013 (aged 82) Boston, Massachusetts, US |

| Resting place | Ogidi, Anambra, Nigeria |

| Notable works |

|

| Children | 4, including Chidi and Nwando |

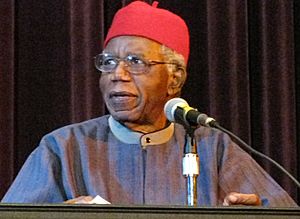

Chinua Achebe (![]() i/ˈtʃɪnwɑː əˈtʃɛbeɪ/; 16 November 1930 – 21 March 2013) was a famous Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic. Many people see him as the most important writer in modern African literature. His first and most famous novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), is a very important book in African literature. It is the most studied, translated, and read African novel ever.

i/ˈtʃɪnwɑː əˈtʃɛbeɪ/; 16 November 1930 – 21 March 2013) was a famous Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic. Many people see him as the most important writer in modern African literature. His first and most famous novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), is a very important book in African literature. It is the most studied, translated, and read African novel ever.

Along with Things Fall Apart, his books No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964) are known as the "African Trilogy." Later novels include A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987). People often call him the "father of African literature," but he didn't like that title.

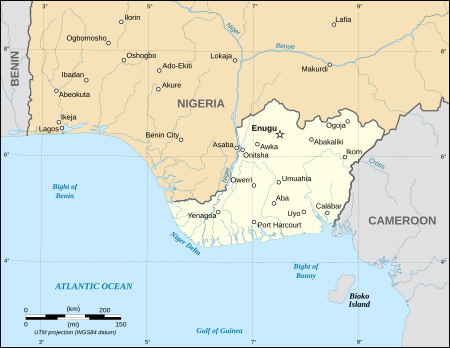

Chinua Achebe was born in Ogidi, British Nigeria. His childhood was shaped by both traditional Igbo culture and Christian beliefs. He was a great student and went to what is now the University of Ibadan. There, he became very critical of how European literature showed Africa. After graduating, he moved to Lagos and worked for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS). His 1958 novel Things Fall Apart made him famous around the world.

In less than 10 years, he published four more novels with Heinemann. He also started the Heinemann African Writers Series, which helped many African writers, like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o and Flora Nwapa, become known.

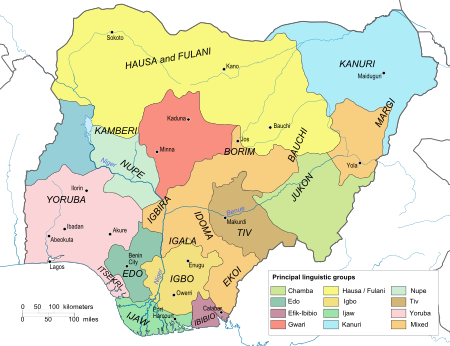

Achebe wanted to change the way African literature was seen. At the time, it was often written from a colonial (European) point of view. He used traditions from the Igbo people, Christian ideas, and the clash between Western and African values to create a unique African voice. He wrote in English and believed it was important to use English to reach many readers, especially in countries that had been colonizers. In 1975, he gave a famous lecture called "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." In this talk, he criticized Joseph Conrad, calling him "a thoroughgoing racist."

When the region of Biafra tried to become independent from Nigeria in 1967, Achebe supported them. He became an ambassador for the Biafran people. The Nigerian Civil War that followed caused a lot of suffering. Achebe asked people in Europe and the Americas for help. After the Nigerian government took back the region in 1970, he joined political parties. However, he soon became disappointed by the corruption and unfairness he saw.

He lived in the United States for several years in the 1970s. In 1990, he moved back to the US after a car crash left him partially disabled. He stayed in the US for 19 years, teaching languages and literature at Bard College. In 2007, he won the Man Booker International Prize. From 2009 until his death, he was a professor of African Studies at Brown University.

Many scholars have studied Achebe's work. Besides his important novels, he also wrote many short stories, poems, essays, and children's books. His writing style uses a lot of the Igbo oral tradition. He combines simple storytelling with folk stories, proverbs (wise sayings), and speeches. His works explore themes like culture and colonialism, gender roles, politics, and history. The Chinua Achebe Literary Festival celebrates his legacy every year.

Contents

- Chinua Achebe's Early Life and Education

- Chinua Achebe's Career as a Writer

- Teaching and Early Writing (1953–1956)

- Things Fall Apart (1957–1960)

- No Longer at Ease and Travels (1960–1961)

- Voice of Nigeria and African Writers Series (1961–1964)

- Arrow of God (1964–1966)

- A Man of the People (1966–1967)

- Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970)

- After the War and Academia (1971–1975)

- Retirement and Politics (1976–1986)

- Anthills of the Savannah and Injury (1987–1999)

- Later Years and Death (2000–2013)

- Chinua Achebe's Writing Style and Themes

- Themes in His Work

- Chinua Achebe's Impact and Legacy

- Writings

- See also

Chinua Achebe's Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Nigeria (1930–1947)

Chinua Achebe was born on November 16, 1930. He was named Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe. His father, Isaiah Okafo Achebe, was a teacher and a Christian preacher. His mother, Janet Anaenechi Iloegbunam, was a leader among church women and a farmer. She was also the daughter of a blacksmith.

He was born near the Igbo village of Ogidi, which was part of British Colonial Nigeria. Both of Achebe's parents were Christian converts. However, they still respected the traditions of their ancestors. This mix of traditional culture and Christian influence greatly affected Chinua and his siblings.

Storytelling was a very important part of Igbo tradition. Achebe's mother and sister, Zinobia, told him many stories when he was a child. His father also had collages, almanacs, and books in their home, which helped his education. Achebe loved traditional village events, like the masquerade ceremonies. He later wrote about these events in his novels and stories.

In 1936, Achebe started primary school at St Philips' Central School in Ogidi. He was very smart and quickly moved to a higher class. One teacher said he had the best handwriting and reading skills. He then went to the famous Government College Umuahia for his secondary education. He was a very dedicated student.

University Years (1948–1953)

In 1948, Nigeria's first university opened. It was called University College (now the University of Ibadan). Achebe was one of the first students admitted. He received a scholarship to study medicine.

During his studies, Achebe became critical of European literature that wrote about Africa. He especially disliked Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. He decided to become a writer after reading Mister Johnson by Joyce Cary. He felt the book showed Nigerian characters in a bad way. Achebe realized the author didn't understand African culture.

He stopped studying medicine and switched to English, history, and theology. This change meant he lost his scholarship and had to pay more for tuition. His family helped him, and his older brother even gave up money for a trip home so Achebe could continue his studies.

Achebe first became a published writer in 1950. He wrote a piece for the University Herald, the university's magazine. He also wrote other essays and letters about philosophy. He was the editor of the Herald in 1951–52. He wrote his first short story, "In a Village Church" (1951), which looked at how Igbo life mixed with Christian ideas. Other short stories he wrote, like "The Old Order in Conflict with the New" (1952) and "Dead Men's Path" (1953), explored the conflicts between old traditions and new ways of life.

After his final exams in 1953, Achebe earned a second-class degree. He was unsure what to do next and went back to his hometown of Ogidi. A friend from university convinced him to apply for an English teaching job at the Merchants of Light school in Oba.

Chinua Achebe's Career as a Writer

Teaching and Early Writing (1953–1956)

As a teacher, Achebe encouraged his students to read a lot and be creative. He taught in Oba for four months. In 1954, he moved to Lagos to work for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS). He wrote scripts for radio talks, which helped him learn how to write realistic conversations.

Lagos was a big city with many people moving from villages. Achebe enjoyed the busy social and political life. He started working on a novel. This was hard because not many African novels had been written in English yet. In 1956, Achebe went to a training school for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in London. This was his first trip outside Nigeria. He used this chance to improve his writing skills and get feedback on his novel.

Things Fall Apart (1957–1960)

Back in Nigeria, Achebe worked on his novel. He named it Things Fall Apart, inspired by a line from a poem by W. B. Yeats. He focused the story on a yam farmer named Okonkwo. The story shows Okonkwo's struggles during the time Nigeria was being colonized.

In 1957, he sent his handwritten manuscript to a typing service in London. When he didn't hear back, his boss, Angela Beattie, visited the company in London. She found the manuscript ignored and demanded it be typed. This was very important for Achebe's writing career. He later said if the novel had been lost, he might have given up writing.

The next year, Achebe sent his novel to a literary agent. Some publishers rejected it, saying there was no market for fiction by African writers. However, Heinemann decided to publish it. An adviser at Heinemann called it "the best novel I have read since the war." Heinemann published 2,000 copies of Things Fall Apart on June 17, 1958.

The book was well-received by the British press. The Times Literary Supplement said it "genuinely succeeds in presenting tribal life from the inside." In Nigeria, opinions were mixed at first. But many soon saw it as an important book. After Things Fall Apart was published, Achebe was promoted at the NBS. He also started dating Christiana Chinwe (Christie) Okoli, who worked at NBS. They later married.

No Longer at Ease and Travels (1960–1961)

In 1960, Achebe published No Longer at Ease. This novel is about Obi, the grandson of Things Fall Apart's main character. Obi is a civil servant in Lagos who gets caught up in corruption. The story shows the conflict between traditional culture and modern society for young Nigerians.

Later that year, Achebe received a Rockefeller Fellowship. This allowed him to travel for six months. He called it "the first important perk of my writing career." He traveled to East Africa, visiting Kenya, Tanganyika, and Zanzibar. He was surprised by how he was treated as "Other" on an immigration form. He also noticed a lack of interest in literature written in the local language, Swahili.

Two years later, Achebe traveled to the United States and Brazil. He met American writers like Ralph Ellison. In Brazil, he discussed the challenges of writing in Portuguese. He worried that important literature might be lost if not translated into more widely spoken languages.

Voice of Nigeria and African Writers Series (1961–1964)

When Achebe returned to Nigeria in 1961, he was promoted to Director of External Broadcasting at the NBS. He helped create the Voice of Nigeria (VON) network, which started broadcasting in 1962. He became concerned about corruption and the silencing of political opponents in Nigeria.

That same year, he attended a conference of African writers in Uganda. He met famous writers like Wole Soyinka. They discussed whether "African literature" should include works from Africans living outside the continent. Achebe felt it was not "a very significant question" at that time. He wrote that the conference was a big step for African literature.

At the conference, Achebe read a novel by a student named James Ngugi (later Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o) called Weep Not, Child. He was impressed and sent it to Heinemann, who published it. Achebe also recommended works by Flora Nwapa. He became the General Editor of the African Writers Series. This collection made books by African writers more available worldwide.

In 1962, Achebe published an essay called "Where Angels Fear to Tread." He criticized how some international authors reviewed African work. He said that "no man can understand another whose language he does not speak." In 1964, he gave a speech called "The Novelist as Teacher."

Family Life

Achebe and Christie married on September 10, 1961. Their first child, Chinelo, was born in 1962. They had two sons, Ikechukwu (1964) and Chidi (1967). When their children started school in Lagos, Achebe and Christie worried about the biased views of Africa in the books and from some teachers. In 1966, Achebe wrote his first children's book, Chike and the River, to help with these concerns.

Arrow of God (1964–1966)

Achebe's third novel, Arrow of God, came out in 1964. He got the idea for the book in 1959 after hearing a story about a Chief Priest being jailed by a British officer. He also found inspiration from Igbo artifacts and old papers from colonial officers.

Like his earlier books, Arrow of God was highly praised by critics. It explores how Igbo tradition and European Christianity mix. The story is set in the village of Umuaro in the early 1900s. It follows Ezeulu, a Chief Priest, who is shocked by the power of British rule. He sends his son to learn the foreigners' ways, which leads to tragedy.

A Man of the People (1966–1967)

Achebe's fourth novel, A Man of the People, was published in 1966. It is a dark satire about a newly independent African country. The story follows a teacher named Odili Samalu who opposes a corrupt Minister of Culture.

When Achebe's friend, John Pepper Clark, read an early copy, he said: "Chinua, I know you are a prophet. Everything in this book has happened except a military coup!" Soon after, a military coup attempt happened in Nigeria. This led to violence and attacks on Igbo Nigerians.

Because of the ending of his novel, military personnel suspected Achebe knew about the coup. He sent his pregnant wife and children to a safe area in the east. They arrived safely, but Christie had a miscarriage. Chinua joined them later.

Once his family was safe, Achebe and his friend Christopher Okigbo started a publishing house called Citadel Press. They wanted to publish more and better books for young readers. One of their first books was How the Leopard Got His Claws.

Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970)

In May 1967, the southeastern part of Nigeria formed the Republic of Biafra. In July, the Nigerian military attacked to stop this rebellion. The Achebe family barely escaped danger many times, including a bombing of their house. In August 1967, Achebe's friend Okigbo was killed fighting in the war. Achebe was deeply affected by this loss.

As the war got worse, the Achebe family had to move. He continued to write, mostly poetry, because it was easier to write shorter pieces during wartime. Many of these poems were in his 1971 book Beware, Soul Brother. One famous poem, "Refugee Mother and Child," showed the suffering around him.

Achebe supported Biafra and became a foreign ambassador for the movement. He traveled to cities in Europe and North America to raise awareness about the situation in Biafra. Meanwhile, his fellow writer Wole Soyinka was jailed for meeting with Biafran officials. Achebe said in 1968 that he felt the Nigerian situation was "untenable."

Conditions in Biafra grew worse. In 1969, Achebe joined other writers on a tour of the United States to highlight the terrible situation. He was shocked by the harsh racist attitudes toward Africa he saw in the US.

In early 1970, the state of Biafra ended. Achebe returned with his family to Ogidi, where their home had been destroyed. He took a job at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka. However, the Nigerian government took away his passport because he supported Biafra, so he couldn't travel. His youngest daughter, Nwando, was born in March 1970.

After the War and Academia (1971–1975)

After the war, Achebe helped start two magazines in 1971: Okike, a literary journal for African art, and Nsukkascope, a university publication. He also helped create Uwa Ndi Igbo to share Igbo stories. In 1972, he released Girls at War, a collection of short stories.

The University of Massachusetts Amherst offered Achebe a professorship in 1972, and his family moved to the United States. His youngest daughter struggled in nursery school because of the language difference. Achebe helped her by telling her stories. He also studied how Africa was seen in Western education. He noted that many Westerners saw Africa as a place without "real people," only "forces."

More Criticism (1975)

Achebe shared more of his criticism in a lecture on February 18, 1975, called "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness." He called Joseph Conrad "a bloody racist." Achebe argued that Conrad's novel Heart of Darkness made Africans seem less human. It showed Africa as a "battlefield" without real people. This lecture was very controversial.

Retirement and Politics (1976–1986)

After teaching in the US, Achebe returned to the University of Nigeria in 1976. He taught English until he retired in 1981. He wanted to finish his novel, restart Okike magazine, and study Igbo culture more. In 1979, he received the first-ever Nigerian National Merit Award.

After retiring in 1981, he spent more time editing Okike. He also became active in the People's Redemption Party (PRP), a left-leaning political party. In 1983, he became the party's deputy national vice-president. He published a book called The Trouble with Nigeria before the elections. In it, he wrote that Nigeria's problem was its leaders' inability to be good examples.

The elections that followed were full of violence and claims of cheating. Achebe felt that Nigerian politicians had gotten worse. He left the PRP and stayed away from political parties. He was sad about the dishonesty he saw. In 1986, he was elected president-general of the Ogidi Town Union and stepped down as editor of Okike.

Anthills of the Savannah and Injury (1987–1999)

In 1987, Achebe released his fifth novel, Anthills of the Savannah. This book is about a military coup in a fictional West African country. It was a finalist for the Booker Prize. Critics praised it as a wise and important book.

On March 22, 1990, Achebe was in a car accident. The car flipped, and his spine was badly damaged. He was flown to a hospital in England. Doctors said he would be paralyzed from the waist down and would need a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Soon after, Achebe became a professor at Bard College in New York. He stayed there for over fifteen years. During the 1990s, he spent little time in Nigeria. However, he remained involved in the country's politics, speaking out against the military leader General Sani Abacha.

Later Years and Death (2000–2013)

In 2000, Achebe published Home and Exile. This book was a collection of his thoughts on living away from Nigeria. In 2007, Achebe won the Man Booker International Prize. The judges praised him for showing writers around the world new ways to tell stories about new realities. Many felt this award corrected a past unfairness to African literature.

Later that year, he published The Education of A British-Protected Child, a collection of essays. He also joined Brown University as a professor. In 2010, Achebe won The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, one of the richest art prizes.

In 2012, Achebe published There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra. This book restarted discussions about the Nigerian Civil War. It was his last book published during his lifetime. Chinua Achebe died after a short illness on March 21, 2013, in Boston, United States. He was buried in his hometown of Ogidi.

Chinua Achebe's Writing Style and Themes

Oral Tradition in His Writing

Achebe's writing style is greatly influenced by the oral tradition of the Igbo people. He includes folk tales in his stories. These tales show the values of the community. For example, a tale in Things Fall Apart about the Earth and Sky shows how men and women depend on each other.

Achebe also used proverbs (wise sayings) to describe the values of the Igbo tradition. He puts them throughout his stories, often repeating points made in conversations. This helps show the community's judgment on individual actions.

Achebe's short stories are not as well known as his novels. He himself didn't think they were a major part of his work. Like his novels, his short stories are influenced by oral tradition. They often have morals that stress the importance of cultural traditions.

Using English Language

During the 1950s, when many countries were becoming independent, there was a big debate about which language writers should use. Achebe's work is known for its topics, its non-colonial viewpoint, and its use of English.

In his essay "English and the African Writer," Achebe explained that colonialism, despite its problems, gave colonized people a common language. This language allowed people from different backgrounds to talk to each other. He used English to reach readers across Nigeria and in colonial countries.

Achebe knew that using English had its challenges. He believed writers needed to take control of the language and make it their own. Achebe's novels did this by changing sentence structure and common phrases. This made the English language sound distinctly African.

Themes in His Work

Tradition and Colonialism

A common theme in Achebe's novels is the meeting of African tradition (especially Igbo traditions) and modern ways. This is often shown through European colonialism. For example, in Things Fall Apart, the village of Umuofia is greatly changed when white Christian missionaries arrive.

The impact of colonialism on the Igbo people in Achebe's novels often comes from European individuals. But institutions and city offices also play a similar role. The character of Obi in No Longer at Ease falls into corruption in the city. The temptations of his job overpower his identity.

Achebe's stories often end with a main character's downfall, which then affects the whole community. For example, Odili's fall into corruption in A Man of the People symbolizes the problems in Nigeria after it gained independence.

Achebe did not try to show things as entirely good or entirely bad. He said in 1972: "I never will take the stand that the Old must win or that the New must win. The point is that no single truth satisfied me." He believed that no one person or idea could be completely right all the time.

Masculinity and Femininity

The roles of men and women, and society's ideas about them, are also frequent themes in Achebe's writing.

Chinua Achebe's Impact and Legacy

Overview of His Influence

Achebe is seen as the most important and influential writer of modern African literature. He has been called the "father of African literature" and the "father of the African novel in English." However, Achebe himself did not like these titles.

Things Fall Apart is described as the most important book in modern African literature. It has sold over 20 million copies worldwide and has been translated into 57 languages. This makes Achebe the most translated, studied, and read African author. His legacy is special because of its huge impact on both African and European literature.

Younger African writers look up to Achebe for advice and inspiration. Scholar Simon Gikandi said that Things Fall Apart "changed the lives of many of us" in Kenya. Outside of Africa, Achebe's influence is also strong. Novelist Margaret Atwood called him "a magical writer—one of the greatest of the twentieth century." Poet Maya Angelou said Things Fall Apart helps readers connect with people from Nigeria. Nobel laureate Toni Morrison said Achebe's work inspired her to become a writer.

Awards and Honors

Achebe received over 30 honorary degrees from universities around the world. These include Dartmouth College, Harvard, and Brown. He also won many other awards, such as the first Commonwealth Poetry Prize (1972) and the Man Booker International Prize (2007). In 1992, he became the first living writer to have his work included in the Everyman's Library collection of classic literature. He was also named a Goodwill Ambassador to the United Nations Population Fund in 1999.

Achebe accepted many awards from the Nigerian government. However, he refused the Nigerian Commander of the Federal Republic award twice, in 2004 and 2011. He said the reasons he rejected it the first time had not been fixed.

Despite his international fame, Achebe never won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Some people, especially Nigerians, felt this was unfair. When asked about it in 1988, Achebe said: "My position is that the Nobel Prize is important. But it is a European prize. It's not an African prize." He believed literature was not a competition.

Memorials and Recognition

Bard College started the Chinua Achebe Center in 2005. It aims to support talented new writers and artists of African origin. Bard also created a Chinua Achebe Fellowship in Global African Studies. In 2013, Achebe was given the title "Ugonabo" of Ogidi by his hometown. This is the highest honor a man can receive in Igbo culture.

In 2016, on Achebe's 86th birthday, young writers in Anambra State began the Chinua Achebe Literary Festival. In 2019, a memorial bust and the Chinua Achebe Literary Court were unveiled at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Achebe was also honored with the Grand Prix de la Mémoire (Grand Prize for Memory) in 2019.

Writings

Novels

- Achebe, Chinua (1958). Things Fall Apart. London: Heinemann.

- —— (1960). No Longer at Ease. London: Heinemann.

- —— (1964). Arrow of God. London: Heinemann.

- —— (1966). A Man of the People. London: Heinemann.

- —— (1987). Anthills of the Savannah. London: Heinemann.

Short stories

- Achebe, Chinua (1951). "In a Village Church".

- —— (1952a). "The Old Order in Conflict with the New". University Herald.

- —— (1953). "Dead Men's Path".

- —— (1960). "Chike's School Days". Rotarian 96 (4): 19–20.

- —— (1962a). The Sacrificial Egg and Other Stories. Onitsha: Etudo Ltd..

- —— (1965). The Voter.

- —— (1971). "Civil Peace". Okike 2.

- —— (1972). "Sugar Baby". Okike 3: 8–16.

- —— (1972a). Girls at War and Other Stories. London: Heinemann.

- African Short Stories: Twenty Stories from Across the Continent. Portsmouth: Heinemann. 1985.

- The Heineman Book of Contemporary African Short Stories. Portsmouth: Heinemann. 1992.

Poetry

- Achebe, Chinua (1951–1952). "There was a Young Man in Our Hall". University Herald 4 (3): 19.

- —— (1971). Beware Soul Brother and Other Poems. Enugu: Nwankwo-Ifejika.

- —— (1973). Christmas in Biafra and Other Poems. Garden City: Doubleday.

- —— (1973). "Flying". Okike 4: 47–48.

- —— (1974). "The Old Man and the Census". Okike 6: 41–42.

- Don't Let Him Die: An Anthology of Memorial Poems for Christopher Okigbo. Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers. 1978.

- ——; Lyons, Robert (1998). Another Africa. New York: Anchor Books.

- —— (2004). Collected Poems. London: Penguin Books.

Essays, criticism and articles

- Achebe, Chinua (21 February 1951). "Philosophy". The Bug: 5.

- —— (1951). "An Argument Against the Existence of Faculties". University Herald 4 (1): 12–13.

- —— (1951–1952). "Editorial". University Herald 4 (3): 5.

- —— (1952). "Editorial". University Herald 5 (1): 5.

- —— (29 November 1952). "Mr. Okafor Versus Arts Students". The Bug: 3.

- —— (29 November 1952). "Hiawatha". The Bug: 3.

- —— (January 1958). "Eminent Nigerians of the 19th Century". Radio Times: p. 3.

- —— (January 1959). "Listening in the East". Radio Times: p. 17.

- —— (6 May 1961). "Two West African Library Journals". The Service: p. 15.

- —— (23–29 July 1961). "Amos Tutuola". Radio Times: p. 2.

- —— (7 July 1962). "Writers' Conference: A Milestone in Africa's Profress". Daily Times: p. 7.

- —— (15 July 1962). "Conference of African Writers". Radio Times: p. 6.

- —— (December 1962). "Review of Christopher Okigbo's Heavensgate". Spear: 41.

- —— (January 1963). "Review of Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo's Twenty-Four Poems". Spear: 41.

- —— (June 1963). "A Look at West African Writing". Spear: 26.

- —— (1963). "Voice of Nigeria–How it Began". Voice of Nigeria 1 (1): 5–6.

- —— (December 1963). "Are We Men of Two Worlds?". Spear: 13.

- —— (1963). "On Janheinz Jahn and Ezekiel Mphahlele". Transition 8: 9. doi:10.2307/2934524.

- —— (1964). "The Role of the Writer in a New Nation". Nigerian Libraries 1 (3): 113–119.

- —— (1965). "English and the African Writer". Transition (Indiana University Press) (18): 27–30. doi:10.2307/2934835. ISSN 0041-1191.

- —— (1966). "The Black Writer's Burden". Présence Africaine 31 (59): 135–140.

- —— (1971). "Editorial". Nsukkascope 1: 1–4.

- —— (1971). "Editorial". Nsukkascope 2: 1–5.

- —— (1971). "Editorial". Nsukkascope 3: 4–5.

- —— (1975). "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness". The Chancellor's Lecture Series (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst): 31–43.

- —— (1975). Morning Yet on Creation Day: Essays. London: Heinemann.

- —— (1983). The Trouble With Nigeria. Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers.

- —— (1988). Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays. London: Heinemann.

- —— (2000). Home and Exile. New York: Oxford University Press.

- —— (2009). The Education of a British-Protected Child. London: Penguin Classics.

- —— (2012). There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra. London: Penguin Classics.

- —— (2018). Africa's Tarnished Name. London: Penguin Classics.

Children's books

- Achebe, Chinua (1966). Chike and the River. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ——; Iroaganachi, John (1972). How the Leopard Got His Claws. Enugu: Nwamife.

- —— (1977). The Drum. Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers.

- —— (1977). The Flute. Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishers.

See also

In Spanish: Chinua Achebe para niños

In Spanish: Chinua Achebe para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |