Ivory trade facts for kids

The ivory trade is when people buy and sell ivory. Ivory comes from the tusks of animals like hippos, walruses, narwhals, rhinos, and even ancient mammoths. Most often, it comes from African and Asian elephants.

People in Africa and Asia have traded ivory for hundreds of years. This trade has led to rules and bans to protect animals. Ivory used to be popular for making piano keys and decorations because of its white color. However, by the 1980s, piano makers started using other materials like plastic. Today, there is also synthetic ivory, which looks like real ivory but is man-made.

Contents

The Trade of Elephant Ivory

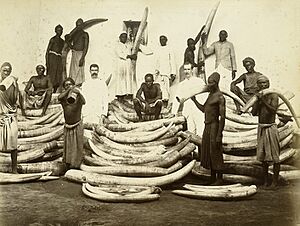

People have traded Elephant ivory from Africa and Asia for thousands of years. Records show this trade happening as far back as 1400 BCE. Moving heavy ivory tusks was always hard. In earlier times, captured people were forced to carry the heavy tusks to ports. Both the tusks and the people were then sold. Ivory was used for things like piano keys, billiard balls, and fancy decorations. Before the 20th century, during the colonization of Africa, about 800 to 1,000 tons of ivory were sent to Europe each year.

World wars and tough economic times slowed down this trade. But in the 1960s and early 1970s, as people became more wealthy, the trade grew again. Japan, after its rules on money were lifted, began buying a lot of raw ivory. This put pressure on the forest elephants in Africa and Asia. Japan preferred hard ivory for making hanko, which are name seals used like signatures. Before this, most seals were made of wood with an ivory tip. But with more money, solid ivory hanko became very popular. Softer ivory from East and Southern Africa was used for souvenirs, jewelry, and small items.

By the 1970s, Japan bought about 40% of the world's ivory. Europe and North America bought another 40%. Much of this ivory was carved in Hong Kong, which was the biggest trading center. The rest of the ivory stayed in Africa. China, which was not as rich then, bought only small amounts to keep its skilled carvers working.

African Elephant Ivory

Poaching and Illegal Trade in the 1980s

In 1979, there were about 1.3 million African elephants in 37 countries. But by 1989, only 600,000 were left. Many ivory traders said that elephants were losing their homes. However, it became clear that the main problem was the international ivory trade. During this decade, about 75,000 African elephants were killed each year for their ivory. This illegal trade was worth about 1 billion dollars. About 80% of this ivory came from elephants killed illegally.

When people discussed how to stop the decline in elephant numbers, they often did not talk about the dangers to people in Africa. They also did not discuss how the ivory trade led to problems like lawlessness. The talks usually focused on elephant numbers and official ivory statistics. People working to stop poaching, like Jim Nyamu, have spoken about the dangers they face from organized poaching groups.

To solve the problem, people focused on controlling international ivory movements. They used rules from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

Even though poaching is still a worry in parts of Africa, it is not the only threat. Fences on farms are becoming more common. These fences can stop elephants from moving freely and can separate herds.

CITES Debates: Attempts to Control and Ban

Some countries in CITES, led by Zimbabwe, believed that wildlife needed to have economic value to survive. They also thought local communities should be involved. Using wildlife without killing it, like for tourism, was widely accepted. But there was a big debate about killing animals for ivory. It was clear that if the ivory trade could not be controlled, the idea of "sustainable use" of wildlife was in danger. In 1986, CITES started a new control system. This system included CITES paper permits, registering large amounts of ivory, and watching legal ivory movements. Most CITES countries and conservation groups like World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) supported these controls.

In 1986 and 1987, CITES registered 89.5 tons of ivory in Burundi and 297 tons in Singapore. Burundi had only one wild elephant, and Singapore had none. It was clear that these large amounts of ivory came mostly from poached elephants. The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a small group, found that international groups behind the illegal trade owned much of this ivory. Well-known traders in Hong Kong benefited from this "amnesty." An elephant expert, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, said the Burundi amnesty "made at least two millionaires." EIA found that these groups not only made a lot of money but also had many CITES permits. They used these permits to smuggle new ivory. This system made ivory more valuable and helped smugglers.

EIA found more problems with this control system. They secretly filmed ivory carving factories run by Hong Kong traders in the United Arab Emirates. They also collected official trade numbers and other proof. The UAE's numbers showed that this country imported over 200 tons of raw ivory in 1987-88. Almost half of this came from Tanzania, where ivory was completely banned. This showed that the traders were easily getting around the system.

Despite these findings and media reports, WWF only supported a ban in mid-1989. This showed how important the "lethal use" idea was to WWF and CITES. Even then, WWF tried to weaken the decisions at the CITES meeting in October 1989.

Tanzania wanted to stop the ivory groups that were causing problems in its society. It suggested putting the African Elephant on Appendix One of CITES. This would mean a ban on international trade. Some southern African countries, like South Africa and Zimbabwe, strongly disagreed. They said their elephant populations were well managed. They wanted to sell ivory to get money for conservation. Both countries were linked to illegal ivory from other African countries. WWF, which had strong ties to these countries, was in a difficult spot. It publicly opposed the trade but privately tried to please these southern African states. However, a proposal from Somalia helped break the deadlock. The ban on elephant ivory trade was then accepted by the CITES delegates.

Finally, at that October CITES meeting, after many debates, the African elephant was placed on Appendix One of CITES. Three months later, in January 1990, the international trade in ivory was banned.

Many people agree that the ivory ban worked. The widespread poaching that affected African elephants was greatly reduced. Ivory prices dropped, and ivory markets around the world closed. Most of these markets were in Europe and the US. It is believed that the ban, along with a lot of public awareness, made people see that the trade was harmful and illegal. Richard Leakey said that ivory piles in Kenya were left unclaimed. It became easier for authorities to stop the killing of elephants.

Southern African Countries Against the Ban

During the discussions that led to the 1990 ivory ban, some southern African countries supported ivory traders from Hong Kong and Japan. They wanted to keep the trade going. These countries, including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and Swaziland, said their elephant populations were well managed. They claimed they needed money from ivory sales for conservation. They voted against the ban and actively tried to reverse it.

South Africa and Zimbabwe led the effort to overturn the ban right after it was agreed upon.

South Africa's claim that its elephants were well managed was not seriously questioned. However, its role in the illegal ivory trade and the killing of elephants in nearby countries was shown in many news reports. This was part of its plan to cause problems for its neighbors. Most of South Africa's elephants were in Kruger National Park. This park was partly run by the South African Defence Force (SADF). The SADF trained and supplied a rebel army in Mozambique called RENAMO. RENAMO was heavily involved in large-scale ivory poaching to fund its army.

Zimbabwe had adopted policies for "sustainable" use of its wildlife. Some governments and WWF saw this as a model for future conservation. People working in conservation praised Zimbabwe's Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE). This program aimed to help local communities with conservation. The failure to stop the ban through CITES was a blow to this movement. Zimbabwe's government said the ivory trade would fund conservation. However, the money instead went to the central government. Its elephant count was accused of counting elephants twice when they crossed the border with Botswana. The ivory trade was also out of control within Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) was involved in poaching in Gonarezhou National Park and other areas.

The debate over the ivory trade involves different national interests. Many different fields of study, like biology, economics, and criminology, make the debate even more complex. The decisions made within CITES are often very political. This can lead to false information and illegal activities.

Southern African countries continue to try to sell ivory through legal systems. In 2002, a group of important elephant scientists wrote an open letter. They explained how the ivory trade affects other countries. They said that the ideas for renewed trade from southern Africa were not like most of Africa. This was because they were based on a South African model where most elephants lived in a fenced national park. They explained South Africa's wealth and its ability to enforce laws within these parks. In contrast, they said most elephants in Africa live in poorly protected, unfenced areas. They ended their appeal by describing the poaching crisis of the 1980s. They stressed that the ban was not to punish southern African countries, but to save elephants everywhere else.

Southern African countries have continued to push for international ivory trade. Led by Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe, they had some success through CITES. Mugabe himself was accused of trading tons of ivory for weapons with China. This broke his country's promise to CITES.

On November 16, 2017, it was announced that US President Donald Trump had lifted a ban on ivory imports from Zimbabwe. This ban had been put in place by Barack Obama.

African Voices in the Ivory Trade Debate

The discussion about the ivory trade has often been seen as Africa versus Western countries.

The novel Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad describes the harsh ivory trade. It shows it as a cruel use of power to get resources for European countries. The book describes the situation in Congo between 1890 and 1910 as "the vilest scramble for loot."

However, southern African countries have always been a small group among the African elephant range states. To show this, 19 African countries signed the "Accra Declaration" in 2006. They called for a complete ban on ivory trade. In 2007, 20 range states met in Kenya and called for a 20-year pause in the trade.

Renewed Ivory Sales

In 1997, CITES countries agreed to allow elephant populations in Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe to be "downlisted." This meant they could trade elephant parts internationally. This decision came with rules to register ivory stockpiles and check trade controls in importing countries. CITES was trying to set up a control system again.

Forty-nine tons of ivory were registered in these three countries. Japan said it had good controls in place, and CITES accepted this. The ivory was sold to Japanese traders in 1997 as an "experiment."

In 2000, South Africa also "downlisted" its elephant population. It wanted to sell its ivory stockpile. In the same year, CITES agreed to create two systems. These systems would inform member states about illegal killing and trade. The two systems, MIKE (Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants) and ETIS (Elephant Trade Information System), have been criticized. Many say they wasted money because they could not prove if ivory sales caused more poaching. They do gather information on poaching and seizures, but not all countries provide full data.

The effect of the ivory sale to Japan in 2000 was highly debated. Traffic, the group that put together the ETIS and MIKE databases, said they could not find any link. However, many people working on the ground said the sale changed how people saw ivory. Many poachers and traders believed they were back in business.

In 2002, over 6 tons of ivory were seized in Singapore. This was a clear warning that poaching in Africa was not just for local markets. Some of the ivory groups from the 1980s were working again. 532 elephant tusks and over 40,000 blank ivory hankos were seized. The EIA found that this case followed 19 other suspected ivory shipments. Four were going to China, and the rest to Singapore, often on their way to Japan. The ivory came from Zambia and was collected in Malawi. It was then shipped from South Africa. Between March 1994 and May 1998, nine suspected shipments were sent by the same company, Sheng Luck, from Malawi to Singapore. After this, they started going to China. Analysis showed company names and directors already known to the EIA from the 1980s. The Hong Kong criminal ivory groups were active again.

In 2002, another 60 tons of ivory from South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia was approved for sale. In 2006, Japan was approved as a place to send the ivory. Japan's ivory controls were seriously questioned. 25% of traders were not even registered. Rules for traders were voluntary, not legal. Illegal shipments were entering Japan. A report by the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society warned that ivory prices jumped. This was due to price fixing by a few manufacturers who controlled most of the ivory. This was similar to how things were controlled when ivory was "amnestied" in the 1980s. Before the sale, China was trying to get approval as an ivory destination country.

In 2014, Uganda said it was looking into the theft of about 3,000 pounds (1,360 kg) of ivory. This ivory was stolen from the vaults of its state wildlife protection agency. Poaching is a big problem in central Africa. This region is said to have lost at least 60% of its elephants in the last ten years.

The Rise of Asia and the Modern Poaching Crisis

Esmond Martin said that when Japan's money rules were lifted in the late 1960s, it started buying huge amounts of raw ivory. Martin also said that in the 1990s, Chinese carvers mainly sold ivory products to people in nearby countries, not to buyers in China. He explained, "These were supplying shops selling small items to tourists and business people from Asian countries like Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Indonesia, where the anti-ivory culture wasn't so strong." He added that they also exported carved ivory to neighboring countries. Chinese people bought some ivory for themselves, but only a small amount.

Will Travers, CEO of Born Free Foundation, said that even if all unregulated markets were closed, there would still be a demand for illegal ivory from countries like China and Japan. To show the lack of ivory controls in China, the EIA shared a Chinese document. It showed that 121 tons of ivory from its official stockpile could not be found. This amount is equal to the tusks from 11,000 elephants. A Chinese official admitted, "this suggests a large amount of illegal sale of the ivory stockpile has taken place." However, a CITES group suggested that CITES approve China's request. WWF and TRAFFIC supported this. China gained its "approved" status on July 15, 2008. China's government has announced that it is banning all ivory trade and carving by the end of 2017. The commercial carving and sale of ivory stopped by March 31, 2017. Conservation group WWF welcomed this news. They called it a "historic announcement... signaling an end to the world's primary legal ivory market."

China and Japan bought 108 tons of ivory in another "one-off" sale in November 2008. This ivory came from Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. At the time, the idea was that these legal sales might lower the price. This would reduce poaching. TRAFFIC and WWF supported this idea. Illegal ivory still enters Japan's ivory market. But since 2012, the demand for ivory has decreased. This is because new awareness campaigns have taught consumers about the link between buying ivory and killing elephants.

China's growing involvement in building projects in Africa and buying natural resources has worried many conservationists. They fear that the removal of animal parts is increasing. Since China was approved as a buyer by CITES, ivory smuggling seems to have increased a lot. WWF and TRAFFIC, who supported the China sale, say the increase in illegal ivory trade might be a "coincidence." But others are less careful. Chinese people working in Africa have been caught smuggling ivory in many African countries. At least ten were arrested at Kenyan airports in 2009. In many African countries, local markets have grown, making ivory easy to get. However, the Asian ivory groups are the most harmful, buying and shipping tons at a time.

CITES had suggested that prices might go down. But the price of ivory in China has greatly increased. Some believe this might be due to price fixing by those who bought the ivory. This echoes warnings from the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society about price-fixing after sales to Japan in 1997. It also reminds people of the monopoly given to traders who bought ivory from Burundi and Singapore in the 1980s. It might also be because more Chinese people can now buy luxury goods. A study funded by Save the Elephants showed that the price of ivory tripled in China in four years after 2011. This was when destruction of ivory stockpiles became more common. The study concluded that this led to more poaching.

A study in 2019 reported that African elephant poaching was decreasing. The highest rate of elephant deaths from poaching was over 10% in 2011. It fell to below 4% by 2017. The study found strong links between poaching rates and ivory demand in Chinese markets. It also found links between poaching rates and corruption and poverty. Based on these findings, the study authors suggested reducing ivory demand in China and other main markets. They also suggested decreasing corruption and poverty in Africa.

In 2012, The New York Times reported a big increase in ivory poaching. About 70% of this ivory went to China. At the 2014 Tokyo Conference on Combating Wildlife Crime, maps were shown that linked illegal ivory seizures to poaching incidents.

The ivory trade has been a continuing problem that has reduced the number of African elephants and white rhinos. In 2013, a single seizure in Guangzhou found 1,913 tusks. This meant nearly 1,000 dead animals. In 2014, Ugandan authorities had 1,355 kg (2,987 lb) of ivory stolen from a safe. This ivory was guarded by police and the army. Valued at over $1.1 million, this was a serious concern. This loss was found during a check of the Uganda Wildlife Authority. This led to an investigation of those who should have protected the ivory. So far, five Wildlife Authority staff members have been suspended.

Major places for ivory trafficking in Vietnam include Mong Cai, Hai Phong, and Da Nang. One of the main traffickers of illegal ivory from Togo is a Vietnamese person, Dao Van Bien. He was sentenced to 22 months. Hong Kong is the largest market for selling elephant ivory. It has been criticized for causing the killing of elephants to meet demand, mainly from mainland China. A 101 East report called Hong Kong "one of the biggest ivory laundering centers in the world." 95 kg (209 lb) of elephant ivory was taken at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris. Two Vietnamese people were arrested by French customs.

The Philippines is a major center for the ivory trade. A priest named Monsignor Cristobal Garcia was linked by National Geographic to a scandal about his involvement in the trade.

African elephant ivory has entered Thailand's Asian elephant ivory market.

Large amounts of ivory are still being imported by Japan.

Vientiane, Laos, is a major place for Chinese tourists looking to get around China's rules on ivory sales. Ivory is sold openly there. This includes at San Jiang Market, in the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, and in Luang Prabang Province.

In 2018, a study by Avaaz, supported by Oxford University, suggested that legal antique ivory trading in the European Union still encourages the poaching of elephants. It is believed that a legal loophole allows the sale of old ivory. This might hide the sale of items made from ivory from recently killed elephants.

Possible Funding for Terrorist Groups

Some officials and media have claimed a link between terrorism and the ivory trade. Reports from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) quoted an unnamed source within the group Al-Shabaab. This source claimed the group was involved in ivory trafficking. The claim that Al-Shabaab received up to 40% of its money from selling elephant ivory gained more attention after the 2013 Westgate shopping mall attack in Nairobi, Kenya.

However, a report by Interpol and the United Nations Environment Programme said these claims were not reliable. The report stated that Al-Shabaab's main income came from informal taxes and the trade in charcoal.

It is possible that some Somali poachers paid money to Al-Shabaab when smuggling ivory through their area. This would be only a small part of the group's total income. Somalia was a popular place for illegal trade. There are still laws against poaching. But like with all illegal materials, people will always find ways to get around them.

Asian Elephant Ivory

International trade in Asian elephant ivory was banned in 1975. This happened when the Asian elephant was placed on Appendix One of CITES. By the late 1980s, it was thought that only about 50,000 Asian elephants remained in the wild.

There has been little disagreement about banning trade in Asian elephant ivory. However, the species is still threatened by the ivory trade. Many conservationists have supported the African ivory trade ban. This is because evidence shows that ivory traders do not care if their ivory comes from Africa or Asia. CITES decisions on ivory trade affect Asian elephants. For detailed carving, Asian ivory is often preferred.

London Conference on Illegal Wildlife Trade

The London Conference on the Illegal Wildlife Trade was held on February 12 and 13, 2014. The goal of this conference was to recognize "the significant scale and harmful economic, social and environmental consequences of the illegal trade in wildlife." The countries aimed to make a political promise and ask the world to work together to end this trade. One main concern was to re-evaluate ways to protect African elephants and stop the illegal trade of their ivory. While 46 countries signed this agreement, The Guardian reported in 2015 that the elephant poaching crisis had not improved. One article quoted William Hague saying the deal would "mark the turning point in the fight to save endangered species." But wildlife experts and the UK government said it was too early to judge if the agreement was effective.

On October 6, 2017, the UK government announced plans to ban the sale and export of ivory in parts of the United Kingdom.

2018 UK Ivory Act

On December 20, 2018, the UK Ivory Act 2018 became law after being passed by the British parliament. This Act might be extended to include hippos, walruses, and narwhals in the future. When the ban takes effect, it will be one of the "world's toughest" ivory bans. It will ban the buying and selling of almost all forms of ivory in the UK, with only a few small exceptions.

Walrus Ivory

People have traded walrus ivory for hundreds of years in many northern parts of the world. Groups like the Norse, Russians, other Europeans, the Inuit, and people of Greenland were involved.

Walrus Ivory in North America

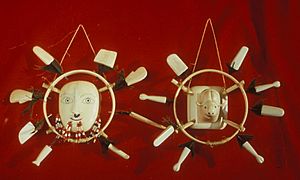

The United States government allows Alaska natives (including first nations, Inuit, and Aleuts) to hunt walrus for food. They must not waste any part of the animal. Natives can sell the ivory from hunted walruses to non-natives. But it must be reported to a United States Fish and Wildlife Service representative, tagged, and made into a handicraft. Natives can also sell ivory found near the ocean (called beach ivory) to non-natives. This ivory also needs to be tagged and worked in some way. Fossilized ivory is not regulated. It can be sold without registering, tagging, or crafting. In Greenland, before 1897, the Royal Greenland Trade Department bought walrus ivory only for sale within the country. After that, walrus ivory was exported. Walrus ivory was used to create art and chess pieces in the Middle Ages.

Bering Strait Fur Trade Network

In the 1800s, Bering Strait Inuit traded walrus ivory, among other things, with the Chinese. In return, they received glass beads and iron goods. Before this, the Bering Strait Inuit used ivory for practical items like harpoon points and tools. Walrus ivory was only used for games during celebrations and for children's toys.

Walrus Ivory in Russia

Moscow is a major center for the trade in walrus ivory. It provides this material for a large foreign market.

Narwhal Ivory

Narwhal Ivory in Greenland

The people of Greenland likely traded narwhal ivory among themselves before they met Europeans. For hundreds of years, narwhal tusks have moved from Greenland to international markets.

In the 1600s, the Dutch traded with the Inuit. They usually exchanged metal goods for narwhal tusks, seal skins, and other items.

Trading continues today between Greenland and other countries. Denmark is by far the main buyer.

Narwhal Ivory in Canada

The Canadian government has banned the international export of narwhal tusks from 17 Nunavut communities. Inuit traders in this region are challenging the ban in Federal Court. The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans limits the export of narwhal tusks and related products from these communities, including Iqaluit.

Tusks in good condition can be worth up to $450 per meter. The ban affects both carved items and raw tusks.

The Canadian government has stated that if it does not limit the export of narwhal tusks, the international community might completely ban exports under CITES.

Tusks are still allowed to be traded within Canada.

Mammoth Ivory

The first known time mammoth ivory reached Western Europe was in 1611. A piece bought from Samoyeds in Siberia arrived in London.

After 1582, when Russia took control of Siberia, mammoth ivory became more regularly available. Siberia's mammoth ivory industry grew a lot from the mid-18th century onwards. For example, in 1821, a collector brought 8,165 kg (18,000 lb) of ivory from about 50 mammoths back from the New Siberian Islands.

It is estimated that 46,750 mammoths have been dug up in the first 250 years since Siberia became part of Russia.

In the early 1800s, mammoth ivory was a major source for products like piano keys, billiard balls, and decorative boxes.

In 1998, over 300 mammoth tusks were found in an underground ice cave in the Taimyr Peninsula in North Siberia. These fossils and tusks were studied until 2003. Then, 24 of them were stolen and taken to Russia. The person suspected was caught and arrested. But too much damage was done to continue studying these mammoth tusks.

Images for kids

See also

- Animal–industrial complex

- African Wildlife Foundation

- Destruction of ivory

- Environmental crime

- Elephants in Thailand

- Synthetic ivory: This material can be used instead of real ivory.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |