Aleut facts for kids

| унаӈан (unangan) унаӈас (unangas) |

|

|---|---|

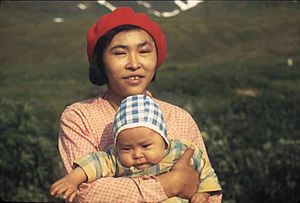

Attu Aleut mother and child, 1941

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

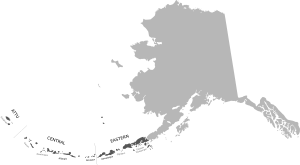

| United States Alaska |

6,752 |

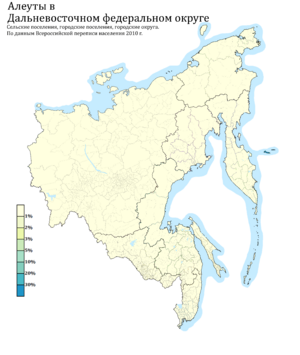

| Russia Kamchatka Krai |

482 |

| Languages | |

| English, Russian, Aleut | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodoxy (Russian Orthodox Church), Animism |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Inuit, Yupik, Sirenik, Sadlermiut | |

The Aleuts (pronounced A-lee-OOT) are the native people of the Aleutian Islands. These islands are found between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. The Aleut people and their islands are split between the US state of Alaska and the Russian area of Kamchatka Krai.

Contents

What does "Aleut" mean?

In their own language, the Aleut people call themselves Unangan (eastern dialect) or Unangas (western dialect). Both names mean "people." The Russian word "Aleut" was a general term. It was used for the people of the Aleutian Islands and their neighbors.

How do Aleuts communicate?

Aleut people speak Unangam Tunuu, which is the Aleut language. They also speak English in the United States and Russian in Russia. About 150 people in the US and five in Russia speak Aleut today.

The Aleut language is part of the Eskimo-Aleut language family. It has three main dialects:

- Eastern Aleut: Spoken on the Eastern Aleutian, Shumagin, Fox, and Pribilof Islands.

- Atkan: Spoken on Atka and Bering islands.

- Attuan: This dialect is now extinct.

The Pribilof Islands have the most people who actively speak Unangam Tunuu. Many older Aleut people speak the language. However, it is rare for younger people to speak it fluently.

Aleut was first written using the Cyrillic script in 1829. Since 1870, it has been written using the Latin script. An Aleut dictionary and grammar have been created. Parts of the Bible have also been translated into Aleut.

Aleut Groups and Where They Live

The Aleut people have different groups based on their dialects:

- Attuan dialect groups:

- Sasignan (Near Islanders): Found in the Near Islands (Attu, Agattu, Semichi).

- Kasakam Unangangis (Russian Aleut): Found in the Commander Islands of Russia (Bering, Medny).

- Qax̂un (Rat Islanders): Found in Buldir Island and the Rat Islands (Kiska, Amchitka, Semisopochnoi).

- Atkan dialect (Western Aleut) groups:

- Naahmiĝus (Delarof Islanders): Found in the Delarof Islands (Amatignak) and Andreanof Islands (Tanaga).

- Niiĝuĝis (Andreanof Islanders): Found in the Andreanof Islands (Kanaga, Adak, Atka, Amlia, Seguam).

- Eastern Aleut dialect groups:

- Akuuĝun or Uniiĝun (Islanders of the Four Mountains): Found in the Islands of Four Mountains (Amukta, Kagamil).

- Qawalangin (Fox Islanders): Found in the Fox Islands (Umnak, Samalga, western Unalaska).

- Qigiiĝun (Krenitzen Islanders): Found in the Krenitzin Islands (eastern Unalaska, Akutan, Akun, Tigalda).

- Qagaan Tayaĝungin (Sanak Islanders): Found in the Sanak Islands (Unimak, Sanak).

- Taxtamam Tunuu dialect of Belkofski.

- Qaĝiiĝun (Shumigan Islanders): Found in the Shumagin Islands.

Where Aleuts Live Today

Historically, Aleut people lived across the Aleutian Islands, the Shumagin Islands, and the western Alaska Peninsula. Before Europeans arrived, their population was about 25,000.

In the 1820s, the Russian-American Company moved many Aleut families. They went to the Commander Islands in Russia and the Pribilof Islands in Alaska. These areas still have many Aleut communities today.

In 2000, about 11,941 people identified as Aleut. Nearly 17,000 people said they had some Aleut ancestors. The Aleut population faced challenges in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Many people became sick from new diseases they had not been exposed to before. Their traditional ways of life also changed.

Aleut History

After Russian Contact

When Russian Orthodox missionaries arrived in the late 1700s, many Aleuts became Christian. Today, most Russian Orthodox churches in Alaska have a majority of Alaska Native members. One of the first Christian martyrs in North America was Saint Peter the Aleut.

Conflict with Russian Traders

In the 1700s, Russian traders set up posts on the islands. They wanted furs that the Aleuts hunted. In May 1784, Aleuts on Amchitka Island protested against the Russian traders. The Aleuts said that otters were becoming fewer. The Russians were also paying less for the furs. The Aleut leaders tried to negotiate for more supplies. This led to a serious conflict.

Conflict with the Nicoleño Tribe in California

In 1811, Aleut hunters traveled to San Nicolas Island in California to hunt otters. The local Nicoleño people asked for payment because so many otters were being hunted. A disagreement turned into a battle. The Aleut hunters killed almost all the Nicoleño men. This, along with diseases, greatly reduced the Nicoleño population. By 1853, only one Nicoleño person was left alive. This person was Juana Maria, known as The Lone Woman of San Nicolas.

Internment During World War II

In June 1942, during World War II, Japanese forces took over Kiska and Attu Islands. They took the people from Attu Island as prisoners to Hokkaidō, Japan. They lived in very difficult conditions.

The U.S. government worried about more Japanese attacks. They moved hundreds of Aleuts from the western islands and the Pribilofs. These Aleuts were placed in internment camps in southeast Alaska. Many people got sick and died from diseases like measles and influenza. These diseases spread quickly in the crowded camps.

In total, about 75 Aleuts died in American internment camps. Another 19 died because of the Japanese occupation. The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 was passed by the U.S. Congress. It aimed to pay back the survivors for what they went through. On June 17, 2017, the U.S. government officially apologized for the internment and treatment of the Unangan people.

Population Changes

Before outside influences, there were about 25,000 Aleuts. New diseases and changes to their society greatly reduced their numbers. By 1910, only 1,491 Aleuts were counted. In 2000, 11,941 people identified as Aleut. Nearly 17,000 said they had Aleut ancestors.

Aleut Culture

Homes

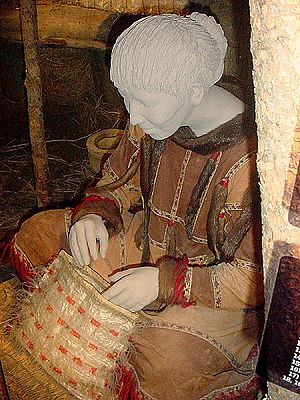

The Aleut people built houses called barabaras. These homes were partly underground. They kept people dry from rain and warm from the cold winds. Aleuts dug an oblong pit in the ground. It was usually about 50 by 20 feet (15 by 6 meters). They covered the pit with a roof made of driftwood. This was thatched with grass and then covered with earth for insulation. Inside, trenches were dug along the sides. Mats were placed on top to keep them clean. Bedrooms were at the back. Several families would live in one house, each with their own area. Instead of fires, they used lanterns for light.

Food and Hunting

The Aleut people got their food by hunting and gathering. They fished for salmon, crabs, shellfish, and cod. They also hunted sea mammals like seals, walrus, and whales. They prepared fish and sea mammals in different ways: dried, smoked, or roasted. They also ate caribou, muskoxen, deer, and moose. Berries were dried or mixed with fat and fish to make a dish called alutiqqutigaq. The boiled skin and blubber of whales and walruses were special foods.

Today, many Aleut people still eat traditional foods. They also buy processed foods from outside Alaska, which can be expensive.

Art and Craftsmanship

Aleut art includes making weapons, building special hunting boats called baidarkas, weaving, carving, and making masks. Both men and women carved ivory and wood. In the 1800s, craftsmen were famous for their beautiful wooden hunting hats. These hats had colorful designs and were decorated with sea lion whiskers, feathers, and walrus ivory.

Aleut women sewed waterproof parkas from seal gut. They also wove fine baskets from sea-lyme grass. Some Aleut women still weave ryegrass baskets today. Aleut arts are taught and practiced across Alaska. As Aleuts have moved, they have shared their traditional knowledge. They also use new materials and methods in their art, like screen printing and video art.

Aleut carving was unique in each area. It attracted traders for hundreds of years. Historically, carving was mainly done by men. Today, both men and women carve. They often carved walrus ivory and driftwood for hunting weapons. Their carvings showed local animals like seals and whales. They also carved human figures.

Aleuts also carved walrus ivory for jewelry and sewing needles. Jewelry designs were specific to each region. Each family group had a special style. They made ornaments for piercing lips, noses, and ears, and for necklaces. Women made their own sewing needles, often with animal heads carved on the ends.

Basket weaving was an art for women. Early Aleut women made baskets and mats of amazing quality. They used only their long, sharpened thumbnails as tools. Today, Aleut weavers still make woven grass items that feel like cloth. These are modern art pieces with ancient roots. Birch bark, puffin feathers, and baleen are also used in basketry. The Aleut word for a grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii. Anfesia Shapsnikoff was an Aleut leader known for teaching and bringing back Aleut basketry.

Masks were made to show figures from their myths and stories. The Atka people believed that other people lived in their land before them. They showed these ancient beings in their masks. These masks often looked like human-animal creatures. Masks were usually carved from wood and painted with colors from berries or other natural things. Feathers were added for decoration. These masks were used in ceremonies like dances, each with its own meaning.

Tattoos and Piercings

Tattoos and piercings showed what Aleut people had achieved. They also showed their religious beliefs. They thought body art would please animal spirits and keep evil away. They believed evil spirits could enter through body openings. By piercing their nose, mouth, and ears, they hoped to stop evil spirits, called khoughkh, from entering. Body art also made them feel more beautiful and showed their social status.

Before the 1800s, piercings and tattoos were very common, especially for women. Nose pins were common for both men and women. They were usually done a few days after birth. The pins were made of bark, bone, or eagle feathers. Adult women sometimes decorated their nose pins with amber and coral.

Ear piercing was also common. Aleuts pierced holes around their ears with shells, bone, feathers, or amber. Materials from birds were important because birds were thought to protect animals in the spirit world. Men wore sea lion whiskers in their ears to show they were skilled hunters. Aleuts also pierced their lower lips with walrus ivory, beads, or bones. This was for decoration and to show social standing or age. The person with the most piercings was highly respected.

Women started getting tattoos when they reached physical maturity, around age 20. Historically, men got their first tattoo after killing their first animal. This was an important step in their lives. Sometimes tattoos showed social class. For example, a daughter of a wealthy father would get many tattoos to show her father's achievements. They would sew or prick designs on the chin, side of the face, or under the nose.

Aleut Clothing

The Aleut people lived in a very harsh climate. They learned to make clothes that kept them warm. Both men and women wore parkas that went below their knees. Women wore parkas made of seal or sea-otter skin. Men wore bird skin parkas, with feathers facing in or out depending on the weather.

When men hunted on the water, they wore waterproof parkas. These were made from the guts of seals, sea-lions, bears, walruses, or whales. Parkas had hoods and wrist openings that could be tightened to keep water out. Men wore breeches made from seal esophagus skin. Children wore parkas made of soft eagle skin with bird skin caps. They called these parkas kameikas, meaning 'rain gear'.

Sea-lions, harbor seals, and sea otters were common marine mammals. Men brought home the skins and prepared them. Women did the sewing. Preparing animal guts for clothing involved many steps. The guts were turned inside out. A bone knife was used to remove muscle and fat. The gut was then cut, stretched, and dried. It was then cut and sewn to make waterproof parkas, bags, and other containers.

It took 40 tufted puffin skins and 60 horned puffin skins to make one parka. A woman would need a year to make one parka. Each parka lasted two years if cared for properly. All parkas were decorated with bird feathers, seal whiskers, bird beaks, claws, sea otter fur, dyed leather, and caribou hair sewn into the seams.

Women made needles from the wing bones of seabirds. They made thread from animal sinews and fish guts. A thin strip of seal intestine could also be twisted into thread. Women grew their thumbnail long and sharpened it. They could split threads to make them as fine as hair. They used natural paints from berries, hematite, octopus ink, and plant roots to color the threads.

Hunting Tools

Boats

The Aleutian Islands are rough and mountainous. They did not have many natural resources for the Aleut people. They collected stones for weapons, tools, stoves, or lamps. They dried grasses for their woven baskets. For everything else, the Aleuts used the fish and mammals they caught.

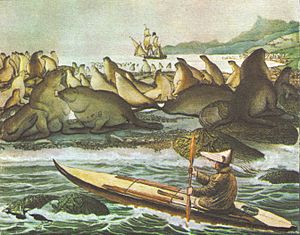

To hunt sea mammals and travel between islands, the Aleuts became expert sailors. For hunting, they used small boats called baidarkas. For regular travel, they used larger boats called baidaras.

The baidara was a large, open boat covered in walrus skin. Aleut families used it to travel among the islands. It was also used to carry goods for trade. Warriors also used them for battle.

The baidarka was a small boat covered in sea lion skin. It was made for hunting because it was strong and easy to steer. The Aleut baidarka looks like a Yup'ik kayak. However, it is designed to be faster and glide better through the water. They made baidarkas for one or two people only. The deck was strong, the sides were almost straight, and the bottom was rounded. Most one-person baidarkas were about 16 feet (5 meters) long and 20 inches (50 cm) wide. Two-person baidarkas were about 20 feet (6 meters) long and 24 inches (60 cm) wide. Aleut men would hunt from these baidarkas on the water.

Weapons

The Aleuts hunted small sea mammals with barbed darts and harpoons. They used throwing boards to launch these weapons. The boards helped them throw with more accuracy and distance.

Harpoons were also called throwing-arrows. The pointed head would fit loosely into the harpoon's shaft. When it hit an animal, the head would detach and stay in the wound. There were three main types of harpoons:

- A simple harpoon: The head stayed in its original position after hitting the animal.

- A compound (toggle-head) harpoon: The head turned sideways inside the animal after hitting it.

- A throwing-lance: Used to kill large animals.

The simple Aleut harpoon had four main parts: a wooden shaft, a bone foreshaft, and a bonehead (tip) with backward-pointing barbs. The barbed head was loosely fitted. When the animal was stabbed, it pulled the head away from the rest of the harpoon. The sharp barbs went in easily but could not be pulled out. The bone tip was tied to a braided string, which the hunter held.

The compound harpoon was the most common Aleut weapon. It was also called a toggle-head spear. It was about the same size as the simple harpoon and used for the same animals. However, it was more effective and deadly. This harpoon separated into four parts. The longest part was the shaft. The shaft fit into the foreshaft, and a bone ring held them together. This ring also protected the wooden shaft from splitting. The toggle head spear tip was connected to the foreshaft. This tip had two parts that broke apart when they hit an animal. The upper part held a sharp stone head. It was attached to the lower part with a small braided loop. Once the tip entered the animal, the upper part broke off. But because it was still connected by the loop, it turned sideways inside the animal's body. This made it harder for the animal to escape.

The throwing lance was different from a harpoon because all its parts were fixed. A lance was used in war. It was also used to kill large marine animals after they had already been harpooned. The throwing lance usually had three parts: a wooden shaft, a bone ring or belt, and a compound head with a barbed bonehead and a stone tip. The length of the compound head was about the distance from a man's chest to his back. The lance would go through the chest and out the back. The bone ring was designed to break after impact. This way, the shaft could be used again.

Burial Customs

The Aleuts buried their dead near their villages. Archaeologists have found many different types of burials in the Aleutian Islands. The Aleut people developed burial styles that fit their local environment and honored the dead. They had four main types of burials: umqan, cave, above-ground sarcophagi, and burials near communal houses.

Umqan burials are the most well-known. People created burial mounds, often on the edge of a cliff. They placed stones and earth over the mound to protect and mark it. These mounds have been found on Unmak Island and date back to early contact periods.

Cave burials have been found throughout the eastern Aleutian Islands. Human remains were buried in shallow graves at the back of caves. These caves were usually near middens (old trash heaps) and villages. Some items have been found with these burials. For example, a disassembled boat was found in a burial cave on Kanaga Island.

Some gravesites found in the Aleutian Islands are above-ground sarcophagi. These are left exposed, not buried in the ground. These burials are often isolated and contain only adult males. This might mean they were part of a special ritual. In the Near Islands, isolated graves have also been found with remains left on the surface.

Another type of burial was near the communal houses of a settlement. Many human remains have been found in these areas. This shows a pattern of burying the dead within the main living areas. These burials were small pits next to and around the houses. Mass graves for women and children were common in these cases. This type of burial has mainly been found in the Near Islands.

Other types of burials have also been found, like mummification or private burial houses. However, these are not considered part of a larger cultural practice.

Unlike some other cultures, the Aleuts usually did not include many items with the dead. Objects to "accompany" the dead are rare. Archaeologists are still trying to understand why there are so few grave goods.

Not much is known about the specific rituals for burying the dead. Archaeologists have not found much evidence about burial ceremonies. This might mean there were no complex ceremonies, or that they have not been discovered yet. Because of this, archaeologists cannot fully understand why certain types of burials were used in specific cases.

Notable Aleuts

- John Hoover (1919–2011), a sculptor.

- Carl E. Moses (1929–2014), a businessman and state representative in Alaska.

- Jacob Netsvetov (1802–1864), a Russian Orthodox saint and priest.

- Sergie Sovoroff (1901–1989), an educator and builder of model sea kayaks (iqya-x).

- Eve Tuck, an academic in indigenous studies.

- Peter the Aleut (1800 - 1815), a Russian Orthodox saint and martyr.

In Popular Culture

- In Snow Crash, a science fiction novel, a main character named Raven is an Aleut. He is shown as incredibly tough and skilled at hunting. The story involves revenge related to how the Aleut people were treated.

- Alaska by James A. Michener.

See Also

In Spanish: Aleutas para niños

In Spanish: Aleutas para niños

- Adamagan

- Aleutian Islands

- Aleutian tradition

- Alutiiq

- Indigenous Amerindian genetics

- Maritime Fur Trade

- Sadlermiut

- Shamanism among Alaska Natives

- Unangan Aleut

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |