Slavery in Africa facts for kids

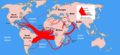

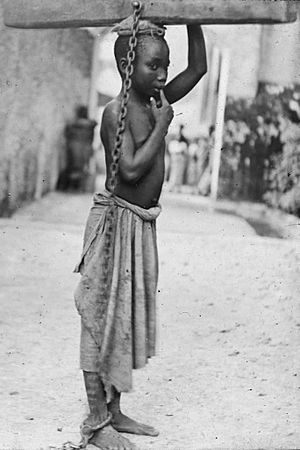

Slavery has been a part of Africa's history for a very long time. Just like in other ancient parts of the world, different forms of servitude and slavery were common. When big slave trades began – like the trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, and Atlantic trades (which started in the 1500s) – many existing African slave systems started providing people for markets outside Africa. Even though it's against the law today, slavery still happens in some parts of Africa.

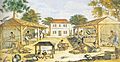

Experts often divide African slavery into two types: indigenous slavery (within Africa) and export slavery (when people were traded outside the continent). Historically, slavery in Africa took many forms. These included debt slavery, making war captives slaves, military slavery, and enslaving criminals. Slavery for household work and court duties was common across Africa. There was also plantation slavery, especially on the east coast and in parts of West Africa. This type of slavery grew in the 1800s after the Atlantic slave trade was stopped. Many African states that relied on the international slave trade then focused on using enslaved labor for other types of business.

Contents

Understanding Slavery in Africa

Many different kinds of slavery and forced labor have existed throughout African history. These were shaped by local African customs, as well as by the Roman, Islamic, and later, the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery was part of the economy in African societies for many centuries, though how much it was used varied.

For example, Ibn Battuta, who visited the ancient kingdom of Mali in the mid-1300s, noted that people there competed to see who had the most enslaved people. He even received an enslaved boy as a gift. In sub-Saharan Africa, the relationships with enslaved people were often complex. Enslaved individuals sometimes had certain rights and freedoms. There were also rules about selling or treating them. Many communities had different levels of enslaved people. For instance, they might treat those born into slavery differently from those captured in war.

The types of slavery in Africa were often connected to family structures. In many African communities, where land could not be owned, enslaving people was a way to gain influence and expand family connections. This meant enslaved people could become a permanent part of a master's family line. Children of enslaved people could even become closely connected to the larger family and rise to important positions, sometimes even becoming a chief. However, a stigma often remained, and there could be clear differences between enslaved family members and those related to the master by birth.

What is Chattel Slavery?

Chattel slavery is a type of slavery where an enslaved person is treated as the owner's property. This means the owner could sell, trade, or treat the enslaved person like any other possession. Often, the children of the enslaved person also became the property of the master. There is evidence of this type of slavery existing for a long time in the Nile River valley, much of the Sahel, and North Africa. Before written records by Arab or European traders, we have less information about how widespread chattel slavery was in other parts of Africa.

Domestic Service Slavery

Many slave relationships in Africa involved domestic slavery. In this system, enslaved people worked mainly in the master's house but kept some freedoms. Domestic slaves were often seen as part of the master's household. They usually would not be sold to others unless there was a very serious reason. In many cases, these enslaved people could keep the money or goods they earned from their work. They could also marry and pass on land to their children.

Pawnship: Debt Bondage

Pawnship, also known as debt bondage, is when people are used as security to make sure a debt is paid back. The debtor, or a family member (often a child), would work as an enslaved person. Pawnship was common in West Africa. It involved giving a person or a family member to serve someone who provided money. Pawnship was similar to slavery but also different. It could include specific, limited terms of service. Also, family ties would often protect the person from being sold into full slavery. This practice was common in West Africa before Europeans arrived, including among the Akan people, Ewe people, Ga people, Yoruba people, and Edo people.

Military Slavery

Military slavery involved taking and training people to be soldiers. These soldiers would keep their identity as military slaves even after their service. Groups of enslaved soldiers were led by a Patron, who could be a government leader or a warlord. These patrons would use their troops for money and their own political goals.

This was most common in the Nile valley (especially in Sudan and Uganda) with slave military units organized by Islamic leaders. It also happened with war chiefs in Western Africa. The military units in Sudan were formed in the 1800s by large-scale military raids in the area that is now Sudan and South Sudan.

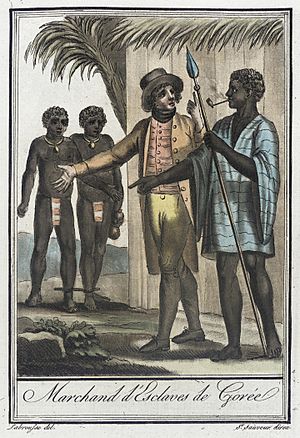

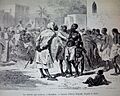

Local Slave Trade in Africa

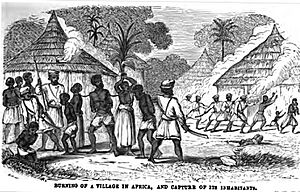

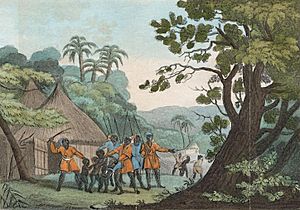

Many nations, like the Bono State, Ashanti (in modern Ghana), and the Yoruba (in modern Nigeria), were involved in trading enslaved people. Groups such as the Imbangala of Angola and the Nyamwezi of Tanzania acted as middlemen or traveling groups. They would wage war on African states to capture people for export as slaves.

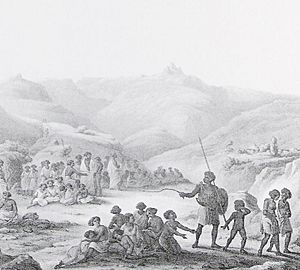

Historians John Thornton and Linda Heywood from Boston University estimate that about 90% of Africans captured and sold to the New World in the Atlantic slave trade were enslaved by other Africans. These Africans then sold them to European traders. Henry Louis Gates, a Harvard professor, has said that the slave trade to the New World would not have been possible on such a large scale without partnerships between African leaders and European traders.

The entire Bubi ethnic group comes from intertribal enslaved people who escaped from various ancient West-central African groups.

Slavery Across Africa

Like most other parts of the world, slavery and forced labor existed in many African kingdoms and societies for hundreds of years. Early European reports from the 1600s about slavery in Africa might not be completely accurate. Some experts say these reports mixed up different kinds of servitude with chattel slavery.

The best information about slave practices in Africa comes from the major kingdoms, especially along the coast. There is less evidence of widespread slavery in societies without a central government. Slave trading was usually a smaller part of other trade relationships. However, there is evidence of a trans-Saharan slave trade route from Roman times that continued after the Roman Empire fell. But family structures and rights given to enslaved people (except those captured in war) seem to have limited the amount of slave trading before the start of the trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, and Atlantic slave trades.

Slavery in North Africa

Slavery in North Africa goes back to ancient Egypt. The New Kingdom (1558–1080 BC) brought many enslaved people as war prisoners up the Nile valley. They were used for household work and supervised labor. Ptolemaic Egypt (305 BC–30 BC) used both land and sea routes to bring in enslaved people.

Chattel slavery was legal and common across North Africa. This was true under Ancient Carthage (around 814 BC – 146 BC) and later when the Roman Empire (145 BC – around 430 AD) and Eastern Romans (533 to 695 CE) controlled the region. A slave trade that brought people from the Sahara across the desert to North Africa, which existed in Roman times, continued. Records from the Nile Valley show this trade was regulated by agreements. As the Roman republic grew, it enslaved defeated enemies, and Roman conquests in Africa were no different. For example, records show Rome enslaved 27,000 people from North Africa in 256 BC. Piracy became a major way to get enslaved people for the Roman Empire. In the 400s AD, pirates would raid coastal North African villages and enslave those they captured. Chattel slavery continued after the Roman Empire fell in the mostly Christian communities of the region.

After the spread of Islamic trade across the Sahara, these practices continued. Eventually, a type of slavery where enslaved people became part of the community spread to major societies at the southern edge of the Sahara, like Mali, Songhai, and Ghana. The medieval slave trade in Europe mainly went to the East and South. The Christian Byzantine Empire and the Muslim World were the destinations, and Central and Eastern Europe were important sources of enslaved people.

The Mamluks were enslaved soldiers who became Muslims. They served the Muslim caliphs and Ayyubid Sultans during the Middle Ages. The first Mamluks served the Abbasid caliphs in 800s Baghdad. Over time, they became a powerful military group. Sometimes, they even took power for themselves, like ruling Egypt from 1250 to 1517. From 1250 on, Egypt was ruled by the Bahri dynasty of Kipchak Turk origin. White enslaved people from the Caucasus served in the army and formed an elite group of troops. They eventually revolted in Egypt to form the Burgi dynasty.

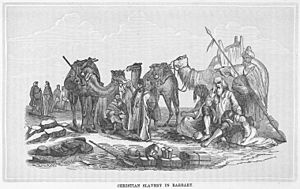

According to Robert Davis, between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire from the 1500s to the 1800s. However, Davis's numbers have been questioned by other historians. They point out that the pirates also captured non-Christian white people from Eastern Europe and black people from West Africa.

Observers in the late 1500s and early 1600s estimated that about 35,000 European Christian slaves were held on the Barbary Coast during this time, mostly in Algiers. Most were sailors taken with their ships, but others were fishermen and coastal villagers. Overall, most captives were from lands close to Africa, especially Spain and Italy.

Coastal villages and towns in Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Mediterranean islands were often attacked by pirates. Long parts of the Italian and Spanish coasts were almost completely abandoned. After 1600, Barbary pirates sometimes went into the Atlantic Ocean and raided as far north as Iceland.

As late as 1798, an islet near Sardinia was attacked by people from Tunisia. Over 900 inhabitants were taken away as slaves.

Sahrawi-Moorish society in Northwest Africa was traditionally divided into several groups. The Hassane warrior tribes ruled and collected payments from the Berber-descended znaga tribes. Below them were enslaved groups known as Haratin, who were a black population.

Enslaved Sub-Saharan Africans were also taken across North Africa into Arabia. They were used for farm work because they were more resistant to malaria, a disease common in Arabia and North Africa at that time. Sub-Saharan Africans could survive in these malaria-ridden lands, which is why North Africans were not transported despite being closer.

Slavery in the Horn of Africa

In the Horn of Africa, the Christian kings of the Ethiopian Empire mainly captured enslaved people from the pagan Nilotic Shanqella and Oromo peoples from their western border areas. They also took people from newly conquered or re-conquered lowland territories. The Somali and Afar Muslim sultanates, like the medieval Adal Sultanate, also traded Zanj (Bantu) slaves. These were captured from the inland areas and sold through their ports.

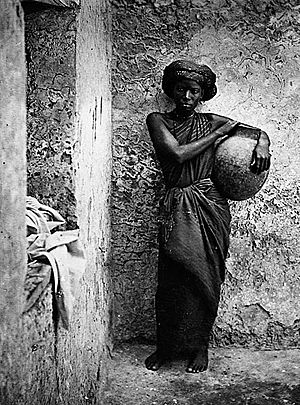

Slavery in Ethiopia was mostly for domestic use and involved more women. This was a common trend in most of Africa. More enslaved women than men were transported across the Sahara, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean trade routes. Enslaved people worked in the homes of their masters or mistresses. They were not used much for making goods. Enslaved people were seen as second-class members of their owners' families.

The first attempt to end slavery in Ethiopia was made by Emperor Tewodros II (ruled 1855–68). However, the slave trade was not officially stopped until 1923 when Ethiopia joined the League of Nations. The Anti-Slavery Society estimated there were 2 million enslaved people in the early 1930s. Slavery continued in Ethiopia until the Italian invasion in October 1935, when the Italian forces abolished it. Due to pressure from Western Allies of World War II, Ethiopia officially ended slavery and forced labor after it regained its independence in 1942. On August 26, 1942, Haile Selassie announced a law outlawing slavery.

In Somali territories, enslaved people were bought in the slave market only to work on plantations. The rules for treating Bantu slaves were set by the decrees of Sultans and local leaders. These plantation slaves often gained their freedom by being set free, escaping, or being bought out of slavery.

Slavery in Central Africa

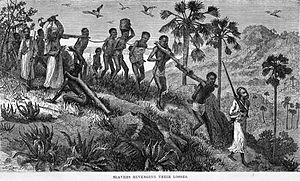

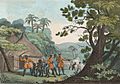

Enslaved people were transported along trade routes crossing the Sahara since ancient times.

Oral stories say slavery existed in the Kingdom of Kongo from its very beginning. Early Portuguese writings show that the Kingdom did have slavery before they arrived. These enslaved people were mainly war captives from the Kingdom of Ndongo.

Slavery was common along the Upper Congo River. In the late 1700s, this area became a major source of enslaved people for the Atlantic slave trade. High slave prices on the coast made long-distance slave trading very profitable. When the Atlantic trade ended, the price of enslaved people dropped sharply. The local slave trade then grew, led by Bobangi traders. The Bobangi also bought many enslaved people with money from selling ivory. They used these people to populate their villages.

Enslaved people who had been sold by their own family group, usually because of bad behavior, were unlikely to try to escape. Selling children was also common during times of hunger. However, captured enslaved people were likely to try to escape. They had to be moved hundreds of kilometers from their homes to prevent this.

The slave trade greatly changed this part of Central Africa. It completely reshaped different parts of society. For example, the slave trade helped create a strong local trade network for food and handmade goods from small producers along the river. Since just a few enslaved people in a canoe could cover the cost of a trip and still make a profit, traders could fill any empty space in their canoes with other goods. They could transport these goods long distances without a big price increase. While the large profits from the Congo River slave trade only went to a few traders, this part of the trade did benefit local producers and consumers.

Slavery in West Africa

Different forms of slavery were practiced in various ways in West African communities before European trade. According to Ghanaian historian Akosua Perbi, local slavery in places like Ghana started by the 1st century AD. However, it was not as common in most non-Islamic West African societies before the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Most West African societies were based on family units, so slavery was a small part of their production. Enslaved people in these societies often had similar roles to free members.

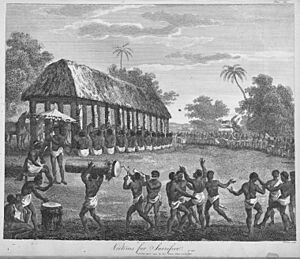

However, Nigerian historian Professor Philip Igbafe says that until the late 1800s, slavery in the Kingdom of Benin and other West African kingdoms had its own place in the state's structure. It was rooted in the "economic, military, social, and political needs of the Benin kingdom." Enslaved people were owned by the Oba (king) and by regular citizens. In pre-colonial Benin, they were acquired in several ways: through wars, as gifts to the Oba, inherited from those who died without a will, and as payments from dependent territories to the Oba and important chiefs. Also, serious criminals were either executed or sold into slavery. Owning many enslaved people showed a person's high status. Enslaved people served in the army and were the main workforce for chiefs. They also served the local need for human sacrifices. Ending slavery later caused many economic, political, and social problems.

Martin Klein has said that before the Atlantic trade, enslaved people in Western Sudan "made up a small part of the population, lived within the household, worked alongside free members of the household, and participated in a network of face-to-face links." With the growth of the trans-Saharan slave trade and gold economies in the western Sahel, some major states became organized around the slave trade. These included the Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire, the Bono State, and Songhai Empire. However, other communities in West Africa largely resisted the slave trade. The Jola refused to join the slave trade until the late 1600s. They did not use enslaved labor in their own communities until the 1800s. The Kru and Baga also fought against the slave trade. The Mossi Kingdoms tried to take over key sites in the trans-Saharan trade. When this failed, they defended themselves against slave raids by powerful states in the western Sahel. The Mossi eventually entered the slave trade in the 1800s, mainly for the Atlantic slave trade.

Senegal was a key place for the slave trade. The map shows it as a starting point for movement and a major trade port. The culture of the Gold Coast was largely based on the power individuals held, rather than land owned by families. Western Africa developed slavery by looking at the benefits for the wealthy and what would best suit the region. This type of rule used slavery as a "political tool" to show status and access. Household and farm labor became more important in Western Africa because enslaved people were seen as "political tools" for power and status. Enslaved people often had more wives than their owners, which increased their owners' status. Enslaved people were not all used for the same purpose. European colonizing countries took part in the trade to meet their own economic needs.

With the start of the Atlantic slave trade, the demand for enslaved people in West Africa grew. Many states became focused on the slave trade, and domestic slavery increased greatly. Hugh Clapperton in 1824 believed that half the population of Kano were enslaved people. Near the Gold Coast, many enslaved people came from deep inside the continent. They were defeated people from many wars and were sold as part of a practice called "eating the country." This aimed to scatter defeated enemies and prevent them from regrouping. According to Ghanaian historian Akosua Perbi, from the 1400s to 1800s in Ghana, major sources of enslaved people were warfare, slave markets, pawning, raids, kidnapping, and tributes. Minor sources were gifts, convictions, and private deals.

In the Senegambia region between 1300 and 1900, almost one-third of the population was enslaved. In early Islamic states of the western Sahel, including Ghana (750–1076), Mali (1235–1645), Segou (1712–1861), and Songhai (1275–1591), about a third of the population was enslaved. In Sierra Leone in the 1800s, about half the population was enslaved. Among the Vai people during the 1800s, three-quarters of the people were enslaved. In the 1800s, at least half the population was enslaved among the Duala of Cameroon and other peoples of the lower Niger, the Kongo, and the Kasanje kingdom and Chokwe of Angola. Among the Ashanti and Yoruba, a third of the population was enslaved. The population of the Kanem (1600–1800) was about one-third enslaved. It was perhaps 40% in Bornu (1580–1890). Between 1750 and 1900, from one- to two-thirds of the entire population of the Fulani jihad states consisted of enslaved people. The population of the largest Fulani state, Sokoto, was at least half-enslaved in the 1800s. Among the Adrar, 15% of people were enslaved, and 75% of the Gurma were enslaved. Slavery was very common among the Tuareg peoples, and some still hold enslaved people today.

When British rule began in the Sokoto Caliphate and nearby areas in northern Nigeria around 1900, about 2 million to 2.5 million people there were enslaved. Slavery in northern Nigeria was finally outlawed in 1936.

Slavery in the African Great Lakes Region

With sea trade from the eastern African Great Lakes region to Persia, China, and India during the first thousand years AD, enslaved people are mentioned as a secondary trade item after gold and ivory. When mentioned, the slave trade seems to have been small-scale. It mostly involved raiding for women and children on the islands of Kilwa Kisiwani, Madagascar, and Pemba. In places like Uganda, the experience for enslaved women was different from common slavery practices at the time. Their roles depended on their gender and position in society.

In the Great Lakes region of Africa (around modern-day Uganda), language evidence shows slavery existed through war capture, trade, and pawning for hundreds of years. However, these forms, especially pawning, seem to have increased significantly in the 1700s and 1800s. These enslaved people were thought to be more trustworthy than those from the Gold Coast. They were seen with more respect because of the training they received.

The words used for enslaved people in the Great Lakes region varied. This region, with its many bodies of water, made it easy to capture and transport enslaved people. Words like captive, refugee, slave, and peasant were all used to describe those in the trade. The difference was made by where and for what purpose they would be used. Methods like pillage, plunder, and capture were all common terms in this region to describe the trade.

Historians Campbell and Alpers argue that there were many different types of labor in Southeast Africa. They say the difference between enslaved and free individuals was not very important in most societies. However, with more international trade in the 1700s and 1800s, Southeast Africa became heavily involved in the Atlantic slave trade. For example, the king of Kilwa island signed a treaty with a French merchant in 1776 to deliver 1,000 enslaved people per year.

Around the same time, merchants from Oman, India, and Southeast Africa started plantations along the coasts and on the islands. To get workers for these plantations, slave raiding and owning enslaved people became very important in the region. Slave traders (especially Tippu Tip) became powerful in the politics of the region. The Southeast African trade reached its highest point in the early 1800s, with up to 30,000 enslaved people sold each year. However, slavery never became a major part of the local economies except in Sultanate of Zanzibar, where plantations and agricultural slavery continued. Author and historian Timothy Insoll wrote that "Figures record the exporting of 718,000 slaves from the Swahili coast during the 19th century, and the retention of 769,000 on the coast." At different times, between 65% and 90% of Zanzibar's population was enslaved. Along the Kenya coast, 90% of the population was enslaved, while half of Madagascar's population was enslaved.

Changes in Slavery in Africa

Slavery in Africa changed due to four major processes: the trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Atlantic slave trade, and efforts to end slavery in the 1800s and 1900s. Each of these greatly changed the types, amount, and economics of slavery in Africa.

Slavery practices in Africa were sometimes used to justify how Europeans interacted with African peoples. Writers in the 1700s in Europe claimed that slavery in Africa was very harsh to make the Atlantic slave trade seem acceptable. Later writers used similar arguments to justify European intervention and eventual colonization to end slavery in Africa.

Africans knew what awaited enslaved people in the New World. Many African leaders visited Europe on slave ships that followed the winds through the New World. For example, Antonio Manuel, the Kongo’s ambassador to the Vatican, went to Europe in 1604. He stopped in Bahia, Brazil, where he arranged to free a countryman who had been wrongly enslaved. African monarchs also sent their children along these same slave routes to be educated in Europe. Thousands of former enslaved people eventually returned to settle Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean Slave Trades

Early records of the trans-Saharan slave trade come from the ancient Greek historian Herodotus in the 400s BC. The Garamentes were recorded by Herodotus as taking part in the trans-Saharan slave trade. They enslaved "Ethiopians" (a Greek term for Black people) who lived in caves. The Berber Garamentes relied heavily on the labor of enslaved people from sub-Saharan Africa. They used enslaved people in their own communities to build and maintain underground irrigation systems called foggara.

In the early Roman Empire, the city of Lepcis set up a slave market to buy and sell enslaved people from inside Africa. The empire placed a tax on the trade of enslaved people. In the 400s AD, Roman Carthage was trading in black enslaved people brought across the Sahara. Black enslaved people seemed to be valued in the Mediterranean as household slaves because of their unique appearance. Some historians argue that the scale of the slave trade during this time might have been larger than in medieval times due to high demand in the Roman Empire.

Slave trading in the Indian Ocean dates back to 2500 BC. Ancient Assyrians and Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Indians, and Persians all traded enslaved people on a small scale across the Indian Ocean (and sometimes the Red Sea). Slave trading in the Red Sea around the time of Alexander the Great is described by Agatharchides. Strabo's Geographica (finished after 23 AD) mentions Greeks from Egypt trading enslaved people at the port of Adulis and other ports on the Somali coast. Pliny the Elder's Natural History (published in 77 AD) also described Indian Ocean slave trading. In the 1st century AD, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentioned opportunities for slave trading in the region. It specifically noted trading "beautiful girls for concubinage." According to this guide, enslaved people were exported from Omana (likely near modern-day Oman) and Kanê to the west coast of India. The ancient Indian Ocean slave trade was possible because of boats that could carry many people across the Persian Gulf. These boats were built with wood imported from India. This shipbuilding goes back to Assyrian, Babylonian, and Achaemenid times.

After the Byzantine Empire and Sassanian Empire became involved in slave trading in the 1st century, it became a major business. Cosmas Indicopleustes wrote in his Christian Topography (550 AD) that enslaved people captured in Ethiopia would be brought into Byzantine Egypt via the Red Sea. He also mentioned the import of non-African eunuchs by the Byzantines from Mesopotamia and India. After the 1st century, exporting black Africans became a "constant factor." Under the Sassanians, the Indian Ocean trade transported not just enslaved people, but also scholars and merchants.

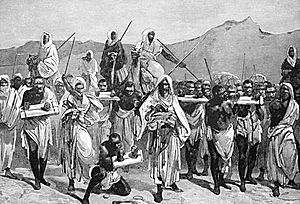

The enslavement of Africans for eastern markets started before the 600s but remained low until 1750. The amount of trade reached its highest point around 1850 but mostly ended around 1900. Muslim involvement in the slave trade began in the 700s and 800s AD. It started with small movements of people, mostly from the eastern Great Lakes region and the Sahel. Islamic law allowed slavery but banned enslaving other existing Muslims. Because of this, the main targets for enslavement were people living in the frontier areas of Islam in Africa. The trade of enslaved people across the Sahara and the Indian Ocean also has a long history. It began when Arab traders gained control of sea routes in the 800s. It is estimated that, at that time, a few thousand enslaved people were taken each year from the Red Sea and Indian Ocean coast. They were sold throughout the Middle East. This trade grew faster as better ships led to more trade and a greater need for labor on plantations. Eventually, tens of thousands per year were being taken. On the Swahili Coast, Afro-Arab slavers captured Bantu peoples from the interior and brought them to the coast. There, the enslaved people slowly became part of the rural areas, especially on the Unguja and Pemba islands.

This changed slave relationships by creating new jobs for enslaved people (like eunuchs to guard harems and in military units). It also created ways for them to gain freedom, such as converting to Islam (though this only freed a slave's children). Although the trade remained relatively small, the total number of enslaved people grew over many centuries. Because it was small and gradual, the impact on slavery practices in communities that did not become Muslim was relatively minor. However, in the 1800s, the slave trade from Africa to Islamic countries increased significantly. When the European slave trade ended around the 1850s, the slave trade to the east grew greatly. It only ended with European colonization of Africa around 1900. Between 1500 and 1900, up to 17 million African slaves were transported by Muslim traders to the Indian Ocean coast, the Middle East, and North Africa.

David Livingstone wrote about the slave trade in East Africa in his journals:

To overdraw its evil is a simple impossibility.

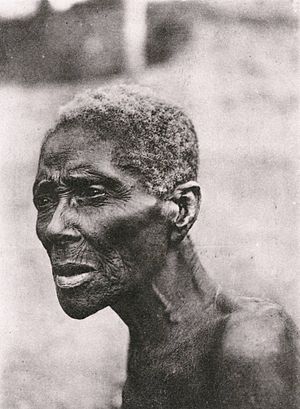

The trans-Saharan routes were as deadly as the trans-Atlantic ones. Deaths of enslaved people in Egypt and North Africa were very high, even if they were fed and treated well. Medieval guides for slave buyers, written in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, explained that Africans from Sudanic and Ethiopian areas were likely to get sick and die in new environments.

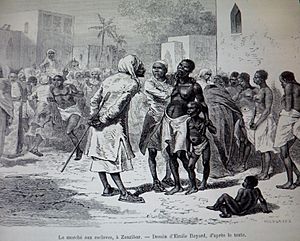

Zanzibar was once East Africa's main slave-trading port. Under Omani Arabs in the 1800s, as many as 50,000 enslaved people passed through the city each year.

European slave trade in the Indian Ocean began when Portugal established Estado da Índia in the early 1500s. Until the 1830s, about 200 enslaved people were exported from Mozambique annually. Similar numbers are estimated for enslaved people brought from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580–1640).

The creation of the Dutch East India Company in the early 1600s led to a quick increase in the slave trade volume in the region. There were perhaps up to 500,000 enslaved people in various Dutch colonies in the 1600s and 1700s in the Indian Ocean. For example, about 4,000 African slaves were used to build the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali and nearby islands supplied regional networks with about 100,000–150,000 enslaved people from 1620–1830. Indian and Chinese slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with perhaps 250,000 enslaved people during the 1600s and 1700s.

The East India Company (EIC) was formed during this period. In 1622, one of its ships carried enslaved people from the Coromandel Coast to the Dutch East Indies. The EIC mostly traded in African slaves but also some Asian slaves bought from Indian, Indonesian, and Chinese slave traders. The French set up colonies on the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in 1721. By 1735, about 7,200 enslaved people lived on the Mascarene Islands, a number that reached 133,000 in 1807. The British captured the islands in 1810. However, because the British had banned the slave trade in 1807, a system of secret slave trade developed to bring enslaved people to French planters on the islands. In total, 336,000–388,000 enslaved people were exported to the Mascarane Islands from 1670 to 1848.

In total, European traders exported 567,900–733,200 enslaved people within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850. Almost as many were taken from the Indian Ocean to the Americas during the same time. However, the slave trade in the Indian Ocean was very small compared to the approximately 12,000,000 enslaved people exported across the Atlantic.

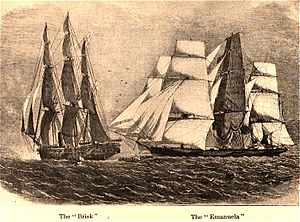

Atlantic Slave Trade: A Major Shift

The Atlantic slave trade, or transatlantic slave trade, happened across the Atlantic Ocean from the 1400s to the 1800s. According to Patrick Manning, this trade greatly changed things. Africans went from being a small group of the world's enslaved population in 1600 to the vast majority by 1800. By 1850, the number of African enslaved people within Africa was more than those in the Americas.

The slave trade quickly grew from a minor part of economies to the largest sector. Also, agricultural plantations grew significantly and became very important in many societies. Economic cities that were the start of main trade routes moved towards the West coast. At the same time, many African communities moved far away from slave trade routes. This often protected them from the Atlantic slave trade but also slowed down their economic and technological growth.

In many African societies, traditional family-based slavery became more like chattel slavery. This was due to an increased demand for work. This led to a general decrease in the quality of life, working conditions, and status of enslaved people in West African societies. Slavery where people were absorbed into families was increasingly replaced with chattel slavery. Family-based slavery in Africa often allowed eventual freedom and also significant cultural, social, and/or economic influence. Enslaved people were often treated as part of their owner's family, not just as property.

In traditional family-based slavery, women were more desired as slaves because of the need for household labor. Male slaves were used for more physical farm work. But as more enslaved men were taken to the West Coast and across the Atlantic to the New World, enslaved women were increasingly used for physical and farm labor. Chattel slavery in America was very demanding because of the physical nature of plantation work. This was the most common destination for male slaves in the New World.

Some argue that the Atlantic slave trade reduced the number of able-bodied people. This limited many societies' ability to farm land and develop. Many scholars believe that the transatlantic slave trade left Africa underdeveloped, with an unbalanced population, and open to future European colonization.

The first Europeans to arrive on the coast of Guinea were the Portuguese. The first European to actually buy enslaved Africans in Guinea was Antão Gonçalves, a Portuguese explorer, in 1441 AD. They were originally interested in trading for gold and spices. They set up colonies on the uninhabited islands of São Tomé. In the 1500s, Portuguese settlers found that these volcanic islands were perfect for growing sugar. Growing sugar needs a lot of labor. Portuguese settlers were hard to attract because of the heat, lack of infrastructure, and hard life. To grow sugar, the Portuguese turned to large numbers of enslaved Africans. Elmina Castle on the Gold Coast, originally built by African labor for the Portuguese in 1482 to control the gold trade, became an important place for enslaved people to be transported to the New World.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to use enslaved Africans in America. They used them on islands like Cuba and Hispaniola. There, the high death rate among the native population led to the first royal laws protecting native people (Laws of Burgos, 1512–13). The first enslaved Africans arrived in Hispaniola in 1501, soon after the Papal Bull of 1493 gave almost all of the New World to Spain.

In Igboland, for example, the Aro oracle (the Igbo religious authority) began condemning more people to slavery for small offenses. These offenses probably would not have been punishable by slavery before. This increased the number of enslaved men available for purchase.

The Atlantic slave trade reached its peak in the late 1700s. This is when the largest number of people were bought or captured from West Africa and taken to the Americas. The increased demand for enslaved people, due to European colonial powers expanding to the New World, made the slave trade much more profitable for West African powers. This led to the creation of several West African empires that thrived on the slave trade. These included the Bono State, Oyo empire (Yoruba), Kong Empire, Imamate of Futa Jallon, Imamate of Futa Toro, Kingdom of Koya, Kingdom of Khasso, Kingdom of Kaabu, Fante Confederacy, Ashanti Confederacy, and the kingdom of Dahomey. These kingdoms relied on constant warfare to get the large numbers of human captives needed for trade with Europeans. It is recorded in the Slave Trade Debates of England in the early 1800s: "All the old writers agree that wars are started only to make slaves, and that Europeans encourage them for that purpose." The gradual end of slavery in European colonial empires during the 1800s again led to the decline and fall of these African empires. When European powers began to stop the Atlantic slave trade, this caused another change. Large slave owners in Africa began to use enslaved people on plantations and for other farm products.

Ending Slavery in Africa

The final major change in slave relationships came with the inconsistent emancipation efforts starting in the mid-1800s. As European authorities began to take over large parts of inland Africa starting in the 1870s, their colonial policies were often confusing about slavery. For example, even when slavery was declared illegal, colonial authorities would sometimes return escaped slaves to their masters. Slavery continued in some countries under colonial rule. In some cases, slavery practices were not significantly changed until independence. Anti-colonial struggles in Africa often brought enslaved people and former slaves together with masters and former masters to fight for independence. However, this cooperation was short-lived. After independence, political parties would often form based on the divisions between enslaved people and masters.

In some parts of Africa, slavery and slavery-like practices continue today. This problem has been difficult for governments and groups to solve.

European efforts against slavery and the slave trade began in the late 1700s. These efforts had a big impact on slavery in Africa. Portugal was the first country in the continent to abolish slavery in mainland Portugal and Portuguese India with a law on February 12, 1761. But this did not affect their colonies in Brazil and Africa. France abolished slavery in 1794. However, slavery was allowed again by Napoleon in 1802 and not abolished for good until 1848. In 1803, Denmark-Norway became the first European country to ban the slave trade. Slavery itself was not banned until 1848. Britain followed in 1807 with the passage of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act by Parliament. This law set high fines, which increased with the number of slaves transported, for captains of slave ships. Britain then passed the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which freed all slaves in the British Empire. British pressure on other countries led them to agree to end the slave trade from Africa. For example, the 1820 U.S. Law on Slave Trade made slave trading piracy, punishable by death. Also, the Ottoman Empire abolished the slave trade from Africa in 1847 under British pressure.

By 1850, when the last major Atlantic slave trade participant (Brazil) passed the Eusébio de Queirós Law banning the slave trade, the slave trades had slowed significantly. Generally, only illegal trade continued. Brazil continued the practice of slavery and was a major source for illegal trade until about 1870. The abolition of slavery became permanent in 1888 when Princess Isabel of Brazil and Minister Rodrigo Silva banned the practice. The British actively worked to stop the illegal Atlantic slave trade during this time. The West Africa Squadron is credited with capturing 1,600 slave ships between 1808 and 1860, freeing 150,000 Africans on board. Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, such as against ‘the usurping King of Lagos’, who was removed from power in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.

According to Patrick Manning, internal slavery was most important to Africa in the second half of the the 1800s. He states that "if there is any time when one can speak of African societies being organized around a slave mode of production, [1850–1900] was it." The end of the Atlantic slave trade caused the economies of African states that depended on the trade to change. They focused on domestic plantation slavery and legal businesses worked by enslaved labor. Before this period, slavery was generally for household purposes.

The ongoing anti-slavery movement in Europe became an excuse and a reason for European countries to conquer and colonize much of Africa. It was the main topic of the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889-90. In the late 1800s, the Scramble for Africa saw the continent quickly divided among European powers. An early, but secondary, goal of all colonial regimes was to stop slavery and the slave trade. Seymour Drescher argues that European interest in abolition was mainly driven by economic and imperial goals. Even though slavery was often used to justify conquest, colonial governments often ignored slavery or allowed it to continue. This was because the colonial state relied on the cooperation of local political and economic structures that were heavily involved in slavery. As a result, early colonial policies usually aimed to end slave trading while regulating existing slave practices and weakening the power of slave masters. Also, early colonial states had weak control over their territories, which prevented widespread abolition efforts. Attempts to abolish slavery became more serious later during the colonial period.

Many things led to the decline and end of slavery in Africa during the colonial period. These included colonial abolition policies, various economic changes, and resistance from enslaved people. Economic changes during the colonial period, such as the rise of paid labor and cash crops, sped up the end of slavery. They offered new economic chances to enslaved people. The end of slave raiding and wars between African states greatly reduced the supply of enslaved people. Enslaved people would use early colonial laws that supposedly abolished slavery. They would move away from their masters, even though these laws often aimed to regulate slavery more than actually end it. This movement led to more serious abolition efforts by colonial governments.

After being conquered and slavery abolished by the French, over a million enslaved people in French West Africa fled from their masters to their old homes between 1906 and 1911. In Madagascar, over 500,000 enslaved people were freed after French abolition in 1896. Because of this pressure, Ethiopia officially abolished slavery in 1932, the Sokoto Caliphate abolished slavery in 1900, and the rest of the Sahel in 1911. Colonial nations were mostly successful in this goal, though slavery is still very active in Africa. It has gradually moved towards a wage economy. Independent nations trying to become more like Western countries or impress Europe sometimes pretended to suppress slavery. This happened even as they, like Egypt, hired European soldiers for expeditions up the Nile. Slavery has never been completely removed in Africa. It commonly appears in African states like Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, and Sudan, in places where law and order have broken down.

Although outlawed in all countries today, slavery is practiced in secret in many parts of the world. There are an estimated 30 million victims of slavery worldwide. In Mauritania alone, up to 600,000 men, women, and children, or 20% of the population, are enslaved. Many are used as bonded labour. Slavery in Mauritania was finally made a crime in August 2007. During the Second Sudanese Civil War, people were taken into slavery. Estimates of abductions range from 14,000 to 200,000. In Niger, where slavery was outlawed in 2003, a study found that almost 8% of the population are still slaves.

Impact of Slavery in Africa

Population Changes and Gender Balance

Slavery and the slave trades greatly affected the size of the population and the balance of genders across much of Africa. The exact impact of these population shifts has been much debated. The Atlantic slave trade took 70,000 people per year, mostly from the west coast of Africa, at its peak in the mid-1700s. The trans-Saharan slave trade involved capturing people from inside the continent. They were then shipped overseas through ports on the Red Sea and elsewhere. This trade reached its highest point at 10,000 people traded per year in the 1600s. According to Patrick Manning, there was a steady population decrease in large parts of Sub-Saharan Africa because of these slave trades. This population decline in West Africa from 1650 until 1850 was made worse because slave traders preferred male slaves. It is important to note that this preference only existed in the transatlantic slave trade. More enslaved women than men were traded within the continent of Africa. In eastern Africa, the slave trade went in many directions and changed over time. To meet the demand for manual labor, Zanj slaves captured from the southern interior were sold through ports on the northern coast. This happened in large numbers over centuries to buyers in the Nile Valley, Horn of Africa, Arabian Peninsula, Persian Gulf, India, Far East, and the Indian Ocean islands.

How Widespread Was Slavery?

The exact extent of slavery within Africa and the trade of enslaved people to other regions is not precisely known. Although the Atlantic slave trade has been studied the most, estimates range from 8 million to 20 million people. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database estimates that the Atlantic slave trade took about 12.8 million people between 1450 and 1900. The slave trade across the Sahara and Red Sea from the Sahara, the Horn of Africa, and East Africa, is estimated at 6.2 million people between 600 and 1600. Although the rate decreased from East Africa in the 1700s, it increased in the 1800s and is estimated at 1.65 million for that century.

Estimates by Patrick Manning suggest that about 12 million enslaved people entered the Atlantic trade between the 1500s and 1800s. However, about 1.5 million died on board ships. About 10.5 million enslaved people arrived in the Americas. Besides those who died on the Middle Passage, more Africans likely died during the wars and slave raids within Africa and forced marches to ports. Manning estimates that 4 million died inside Africa after capture, and many more died young. Manning's estimate includes the 12 million who were originally meant for the Atlantic trade, as well as the 6 million meant for Asian slave markets and the 8 million meant for African markets.

According to David Stannard, 50% of deaths in Africa happened because of wars between native kingdoms. These wars produced most of the enslaved people. This includes those who died in battles and those who died from forced marches to slave ports on the coast. The practice of enslaving enemy fighters and their villages was common throughout Western and West Central Africa. However, wars were rarely started just to get enslaved people. The slave trade was largely a side effect of tribal and state warfare. It was a way to remove potential opponents after victory or to pay for future wars.

Debate on Population Effects

The effects of the slave trade on population are some of the most debated topics. Walter Rodney argued that exporting so many people was a disaster for the population. He believed it left Africa permanently behind compared to other parts of the world. He thought this largely explains Africa's continued poverty. He presented numbers showing that Africa's population stayed the same during this period, while Europe's and Asia's grew greatly. According to Rodney, all other areas of the economy were harmed by the slave trade. Top merchants left traditional industries to pursue slaving, and the general population was disrupted by the slaving itself.

Others have disagreed with this view. J. D. Fage compared the number effect on the continent as a whole. David Eltis has compared the numbers to the rate of emigration from Europe during this period. In the 1800s alone, over 50 million people left Europe for the Americas. This was a much higher rate than were ever taken from Africa.

Others, in turn, challenged that view. Joseph E. Inikori argues that the history of the region shows that the effects were still very harmful. He argues that the African economic model of the period was very different from the European one. It could not handle such population losses. Population reductions in certain areas also led to widespread problems. Inikori also notes that after the slave trade was stopped, Africa's population almost immediately began to grow rapidly, even before modern medicines were introduced.

Impact on Africa's Economy

There is a long-running debate among experts about the harmful effects of the slave trades. It is often claimed that the slave trade weakened local economies and political stability. This happened as villages' important workers were shipped overseas, and slave raids and civil wars became common. With the rise of a large commercial slave trade, driven by European needs, enslaving your enemy became less a result of war and more a reason to go to war. The slave trade is said to have prevented the formation of larger ethnic groups. It caused ethnic divisions and weakened the creation of stable political structures in many places. It is also claimed to have reduced the mental health and social development of African people.

In contrast, J. D. Fage argues that slavery did not have a completely disastrous effect on African societies. Enslaved people were expensive goods, and traders received a lot in exchange for each person. At the peak of the slave trade, hundreds of thousands of muskets, large amounts of cloth, gunpowder, and metals were being shipped to Guinea. African trade with Europe at the peak of the Atlantic slave trade—which also included significant exports of gold and ivory—was about 3.5 million British pounds per year. In comparison, the total trade of the Kingdom of Great Britain, a major economic power at the time, was about 14 million pounds per year during the same period in the late 1700s. As Patrick Manning has pointed out, most items traded for enslaved people were common goods, not luxury items. Textiles, iron ore, currency, and salt were some of the most important goods imported because of the slave trade. These goods spread throughout society, raising the general standard of living.

Although debated, it is argued that the Atlantic slave trade severely damaged the African economy. In 19th-century Yoruba Land, economic activity was described as being at its lowest point ever. Life and property were being taken daily, and normal living was at risk because of the fear of being kidnapped.

The slave trade in Africa also disrupted political systems. The capture and sale of millions of Africans to the Americas and elsewhere meant the loss of many skilled and talented individuals. These people played important roles in African societies. Without them, African societies became unstable, and their political systems grew weaker. This led to instability and civil conflicts, with some societies collapsing entirely. Additionally, the slave trade encouraged warfare and raiding, as people were captured and sold by rival African tribes.

The impact of the slave trade on African political systems was far-reaching and long-lasting. Today, many African countries still face political instability and weak governance. Some scholars point to the legacy of slavery as a contributing factor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Esclavitud en África para niños

In Spanish: Esclavitud en África para niños

- Slavery in contemporary Africa

- Cudjoe Lewis

- Atlantic slave trade

- Blockade of Africa

- Slavery in modern Africa

- Anti-Slavery operations of the United States Navy

- Barbary pirates

- Christianity and slavery

- Islamic views on slavery

- Slavery in Mauritania

- Slavery in Sudan

- Unfree labour

- Maafa

- Tippu Tip

- Abolitionism

- History of slavery

- History of slavery in the United States

- James Riley (Captain)

- Slave ship

- African Diaspora

- Slavery

- Asiento de Negros

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |