Dahomey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Dahomey

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1600–1904 | |||||||||||

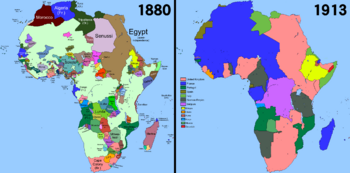

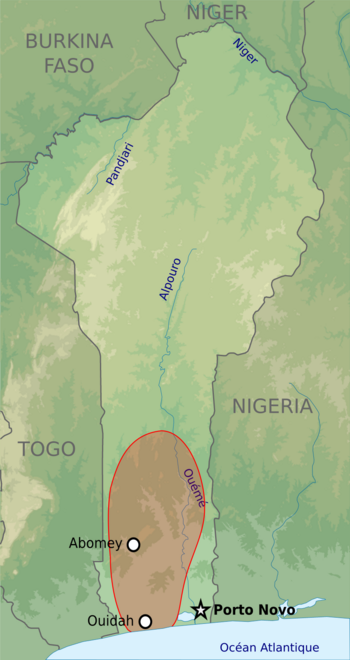

The Kingdom of Dahomey around 1894, superimposed on a map of the modern-day Republic of Benin, in the region of West Africa.

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Kingdom, vassal state of the Oyo Empire (1730–1823), French Protectorate (1894–1904) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Abomey | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Fon | ||||||||||

| Religion | Vodun | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Dahomean | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Ahosu (King) | |||||||||||

|

• c. 1600–1625 (first)

|

Do-Aklin | ||||||||||

|

• 1894–1900 (last)

|

Agoli-agbo | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

|

• Aja settlers from Allada settle on Abomey Plateau

|

c. 1600 | ||||||||||

|

• Dakodonu begins conquest on Abomey Plateau

|

c. 1620 | ||||||||||

|

• King Agaja conquers Allada and Whydah

|

1724–1727 | ||||||||||

|

• King Ghezo defeats the Oyo Empire and ends tributary status

|

1823 | ||||||||||

|

• Annexed into French Dahomey

|

1894 | ||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1904 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1700 | 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 1700

|

350,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Cowrie | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Benin | ||||||||||

The Kingdom of Dahomey was a powerful West African kingdom. It existed from about 1600 until 1904 in what is now Benin. The kingdom started on the Abomey Plateau with the Fon people in the early 17th century.

By the 18th century, Dahomey grew into a major regional power. It expanded south to control important coastal cities like Whydah. This gave it direct access to the Atlantic trade routes. For much of the mid-19th century, Dahomey was a key state. It even stopped paying tribute to the Oyo Empire.

Many European visitors wrote about Dahomey, making it well-known in Europe. The kingdom had an organized economy based on conquest and using captives for work. It also had important international trade and diplomatic ties with Europeans. Dahomey had a strong central government, tax systems, and a well-organized army. Famous parts of the kingdom included its art, an all-female army unit called the Dahomey Amazons, and the detailed religious practices of Vodun.

Dahomey's growth happened at the same time as the Atlantic slave trade grew. It became known as a main supplier of captives. Dahomey was a very militaristic society, always ready for war. It fought wars and raided neighboring areas. Captives were traded for European goods like rifles, gunpowder, fabrics, cowrie shells, tobacco, and pipes. Other captives stayed in Dahomey and worked on royal farms. The Annual Customs of Dahomey were big events. They involved giving gifts, religious Vodun ceremonies, military parades, and important discussions about the kingdom's future.

In the 1840s, Dahomey began to face challenges. The British pushed to end the trade of captives. The British Royal Navy even blocked Dahomey's coast and sent anti-slavery patrols. Dahomey also became weaker after failing to capture people in Abeokuta. This was a Yoruba city-state founded by refugees from the Oyo Empire. Later, Dahomey had land disputes with France. This led to the war in 1890, and part of the kingdom became a French protectorate. The kingdom fell four years later after more fighting. The last king, Béhanzin, was overthrown, and the country became part of French West Africa.

French Dahomey became independent in 1960 as the Republic of Dahomey. It changed its name to Benin in 1975.

Contents

The Name of Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey was known by several names. These included Danxome, Danhome, and Fon. The name Fon comes from the main ethnic and language group of the kingdom's royal families. This is how Europeans first learned about the kingdom.

History of the Kingdom

The Fon people founded the Kingdom of Dahomey around 1600. They had recently settled in the area. Some believe they were a mix of Aja people and local Gedevi people. Houegbadja (around 1645–1685) is often seen as the kingdom's founding king. He built the Royal Palaces of Abomey and started taking over towns outside the Abomey Plateau.

Kings of Dahomey

| King | Start of rule | End of rule |

|---|---|---|

| Do-Aklin (Ganyihessou) | ≈1600 | 1620 |

| Dakodonou | 1620 | 1645 |

| Houégbadja | 1645 | 1680 |

| Akaba | 1680 | 1708 |

| Agaja | 1708 | 1740 |

| Tegbessou (Tegbesu) | 1740 | 1774 |

| Kpengla | 1774 | 1789 |

| Agonglo | 1790 | 1797 |

| Adandozan | 1797 | 1818 |

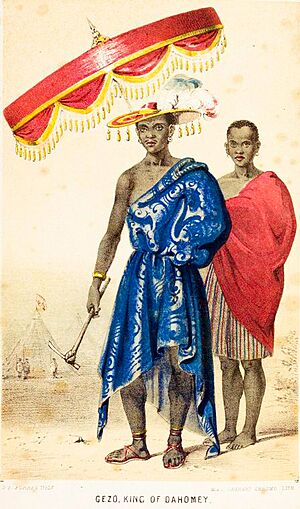

| Guézo (Ghézo/Gezo) | 1818 | 1858 |

| Glèlè | 1858 | 1889 |

| Béhanzin | 1889 | 1894 |

| Agoli-agbo | 1894 | 1900 |

King Agaja's Rule (1708–1740)

King Agaja, Houegbadja's grandson, became king in 1708. He greatly expanded the Kingdom of Dahomey. His strong military made this possible. Dahomey had a professional army of about ten thousand soldiers. They were very disciplined and had good weapons.

In 1724, Agaja conquered Allada, where the royal family was said to have come from. In 1727, he conquered Whydah. This made the kingdom much larger, especially along the Atlantic coast. Dahomey became a major regional power. This led to constant wars with the main regional state, the Oyo Empire, from 1728 to 1740. Dahomey eventually became a tributary to the Oyo Empire, meaning it had to pay them.

King Tegbesu's Rule (1740–1774)

Tegbesu, also spelled Tegbessou, ruled Dahomey from 1740 to 1774. He was not King Agaja's oldest son. He became king after winning a fight for power with his brother. King Agaja had greatly expanded Dahomey, especially by conquering Whydah in 1727. This made the kingdom larger but also caused more problems inside and outside the kingdom.

Tegbesu had to make his rule seem fair to the people he had recently conquered. He made many changes to the kingdom's government to make it stronger. During his rule, the trade of captives grew a lot. This became the king's main source of income. Tegbesu's rule also saw the first important kpojito, or mother of the leopard, with Hwanjile in that role. The kpojito became a very important person in Dahomey's royal family. Hwanjile is said to have changed Dahomey's religious practices. She created two new gods and linked worship more closely to the king.

King Ghezo's Rule (1818–1859)

When King Ghezo became king in 1818, Dahomey faced two big problems. The kingdom was in political trouble and had money problems. First, he needed to make Dahomey independent from the Oyo Empire. Dahomey had been paying tribute to the Yoruba empire of Oyo since 1748. Second, he needed to improve Dahomey's economy. Both goals depended on the trade of captives.

King Ghezo used new military plans to fight against the Oyo, who were also rivals in the trade of captives. He also set rules for Dahomey's part in this trade. Under his rule, people from Dahomey would no longer be traded, as they had been under his brother, Adandozan. Instead, Dahomey would focus on capturing enemies and trading them. King Ghezo also wanted his people to eventually switch to trading palm oil.

Dahomey won a big victory when they defeated the Oyo Empire in 1827. While Brazil's demand for captives increased in 1830, the British started a campaign to end the trade in Africa. The British government put a lot of pressure on King Ghezo in the 1840s to stop the trade in Dahomey. King Ghezo said he could not stop it because of pressure from his own people. He explained that the whole region depended on this trade. Ending it suddenly would cause chaos in his kingdom. King William Dappa Pepple of Bonny and King Kosoko of Lagos felt the same way. King Ghezo suggested expanding the palm oil trade and slowly ending the trade of captives.

King Ghezo's rule was marked by major battles and big changes. He raised the Agojie to a higher status. These "Dahomey Amazons" were key to defeating the Oyo Empire. His rule also made Dahomey one of the most powerful African kingdoms. It stood against British efforts to convert people to Christianity and kept its traditional religion, Vodun. He stopped the sacrifice of captives and removed the death penalty for some smaller crimes. Even though the kingdom had a history of harshness, King Ghezo was often seen as honorable and unbeatable, even by his enemies.

End of the Kingdom

The kingdom fought two wars with France: the First Franco-Dahomean War and the Second Franco-Dahomean War. Dahomey was defeated and became a French protectorate in 1894. This meant France had control over it.

In 1904, the area became part of a French colony called French Dahomey. In 1958, French Dahomey became the self-governing colony called the Republic of Dahomey. It gained full independence in 1960. In 1975, it was renamed the People's Republic of Benin, and in 1991, the Republic of Benin.

Dahomey Today

Today, the kingdom still exists as a constituent monarchy within Benin. Its rulers no longer have official powers under Benin's laws. However, they still have some political and economic influence. Modern kings take part in important Vodun religious festivals and other traditional ceremonies.

How Dahomey Was Governed

Early writings often described the kingdom as an absolute monarchy with a very powerful king. These descriptions were sometimes used in debates about the trade of captives, especially in the United Kingdom. So, they might have been exaggerated. More recent historical work shows that the king's power in Dahomey had limits.

Historian John C. Yoder pointed out the Great Council in the kingdom. He said its actions showed that government decisions were shaped by internal political pressures, not just by the king's orders. The main political divisions were villages with chiefs. These chiefs were appointed by the king and acted as his representatives to settle disagreements in the village.

The King

The King of Dahomey (called Ahosu in the Fon language) was the kingdom's main ruler. All the kings said they belonged to the Alladaxonou dynasty. They claimed to be descendants of the royal family in Allada. Kings Houegbadja, Akaba, and Agaja created many of the rules for who would become king and how the government would work. Usually, the kingship went to the oldest son, but not always.

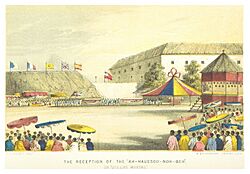

The Great Council usually chose the king through discussions. The Great Council brought together many important people from all over the kingdom each year for the Annual Customs of Dahomey. Discussions were long and included both men and women from across the kingdom. At the end, the king would announce what the group had agreed upon.

Royal Court Officials

Key positions in the King's court included the migan (Prime Minister) and the mehu (Finance Minister). Other important roles were the yovogan, the tokpo (Minister of Agriculture), the agan (army general), the kpojito (or queen mother), and later the chacha (or viceroy) of Whydah. Each of these main positions, except for the kpojito, was held by a man and had a female partner who worked with them.

The migan was a main advisor to the king. He was also a key judge and the head executioner. The mehu was another important officer. He managed the palaces, royal family matters, economic issues, and areas south of Allada. This made his position vital for contact with Europeans.

Dahomey's Relations with Other Countries

Dahomey's relationships with other countries were complex. They were greatly affected by the transatlantic trade of captives.

Brazil

In 1750, Dahomey sent a diplomatic mission to Salvador in the Portuguese colony of Brazil. This was to improve relations after an incident in 1743 led to Portuguese-Brazilian officials being expelled.

More Dahomey missions went to Brazil from 1795 to 1805. Their goal was to strengthen ties with Portuguese colonial officials and buyers of captives. This ensured they would keep buying captives from Dahomey instead of rival kingdoms. In 1823, Dahomey formally recognized Brazil's independence. This made it one of the first countries to do so.

The trade of captives between Brazil and Dahomey stayed strong. This was true even with pressure from the United Kingdom to stop it. Francisco Félix de Sousa, a former captive who became a major trader in the Dahomey region, became very influential. He was given the special title of Chachá, vice-king of Ajudá. He also had a monopoly on exporting captives.

France

In 1861, the kingdom of Porto-Novo, which paid tribute to Dahomey, was attacked by the British Royal Navy. The British were doing anti-slavery patrols. Porto-Novo asked France for protection and became a French protectorate in 1863. King Behanzin of Dahomey did not accept this. He still said Porto-Novo was part of Dahomey.

Another problem was Cotonou. The French believed this port was theirs because of a treaty signed by Dahomey's representative in Whydah. Dahomey ignored all French claims there and kept collecting taxes from the port. These land disputes led to the First Franco-Dahomean War in 1890. France won, and Dahomey had to sign a treaty giving Porto-Novo and Cotonou to the French. Later, Dahomey started raiding the area again and ignored French complaints. This started the Second Franco-Dahomean War in 1892. The kingdom was defeated in 1894. It was then made part of the French colonial empire as French Dahomey, and King Behanzin was sent away to Algeria.

Portugal

The Portuguese fort at Ouidah was destroyed by Dahomey's army in 1743. This happened when Dahomey conquered the city. So, King Tegbesu wanted to restart relations with Portugal. Dahomey sent at least five groups of ambassadors to Portugal and Brazil. This happened in 1750, 1795, 1805, 1811, and 1818. Their goal was to discuss the terms of the Atlantic trade of captives.

These missions led to official letters between the kings of Dahomey and Portugal. Gifts were also exchanged. The Portuguese Crown paid for the travel and stay of Dahomey's ambassadors. They traveled between Lisbon and Salvador, Bahia. The missions of 1805 and 1811 brought letters from King Adandozan. He had imprisoned Portuguese people in Dahomey's capital, Abomey. He asked Portugal to trade only at Ouidah. Portugal promised to meet his demands if he released the prisoners.

A long letter from King Adandonzan, dated October 9, 1810, shows he knew about the Napoleonic Wars. He also knew about the Portuguese royal family moving to Brazil. He said he was sorry he could not help the Portuguese royal family during their war with France. He also asked for news about the wars with France and other nations.

United Kingdom

Dahomey became a target of the British Empire's campaign against the trade of captives in the 19th century. The British sent diplomats to Dahomey. They wanted to convince King Ghezo to stop human sacrifice and the trade of captives. Ghezo did not immediately agree to British demands. Instead, he tried to stay friends with the British by encouraging the growth of new trade in palm oil.

In 1851, the Royal Navy blocked Dahomey's coast. This forced Ghezo to sign a treaty in 1852 that immediately stopped the export of captives. However, this was broken when the trade resumed in 1857 and 1858.

During a diplomatic visit to Dahomey in 1849, Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy received a young girl (later named Sara Forbes Bonetta) from King Ghezo as a "gift." She later became a goddaughter to Queen Victoria.

United States

During the American Revolution, the rebelling United Colonies banned the international trade of captives. They had various reasons, including economic, political, and moral ones. After the revolution, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves in 1807. This law made the international trade of captives illegal in the U.S. However, slavery within the country continued until the American Civil War.

Because of this, the United States never had formal diplomatic relations with the Kingdom of Dahomey. The last known ship that secretly and illegally brought captives to the United States carried 110 people from Dahomey. They were bought long after the trade was banned. This story was in the newspaper The Tarboro Southerner on July 14, 1860. Five days earlier, a ship called Clotilda, led by Captain William Foster, arrived in the bay of Mobile, Alabama. It carried the last known shipment of captives to the U.S.

Yoruba People

The Oyo Empire often fought with the Kingdom of Dahomey. Dahomey paid tribute to Oyo from 1732 until 1823. The city-state of Porto-Novo, protected by Oyo, and Dahomey had a long rivalry. This was mainly over who controlled the trade of captives along the coast. The rise of Abeokuta in the 1840s created another rival to Dahomey. Abeokuta became a safe place for people escaping the trade of captives.

Some notable Yoruba people captured by Dahomey in raids after the Oyo Empire fell include Sara Forbes Bonetta (Aina), Cudjoe Lewis (Oluale Kossola), Matilda McCrear (Abake), Redoshi, and Seriki Williams Abass (Ifaremilekun Fagbemi).

Dahomey's Military

The military of the Kingdom of Dahomey was split into two main parts: the right and the left. The migan controlled the right side, and the mehu controlled the left. By the time of Agaja, the kingdom had a standing army. This army stayed with the king wherever he went.

Soldiers were recruited as young as seven or eight years old. They first served as shield carriers for older soldiers. After years of training and military experience, they could join the army as regular soldiers. To encourage them, each soldier received bonuses in cowry shells for every enemy they killed or captured. This mix of lifelong training and money rewards made the military strong and disciplined. One European said Agaja's army had "elite troops, brave and well-disciplined."

The Dahomey army under Agaja was also well-armed. They preferred European weapons over traditional ones. For example, they used European flintlock muskets for long-range fighting. For close combat, they used imported steel swords and cutlasses. The Dahomey army also had twenty-five cannons. By the late 19th century, Dahomey had many different weapons. These included various rifles and even some early machine guns. Along with firearms, Dahomey used mortars.

When going into battle, the king would let the field commander lead. The reason given was that if any spirit punished the commander for decisions, it should not be the king. Dahomey units trained constantly. They fired on command, used special marching techniques, and formed long lines. They used tactics like covering fire, frontal attacks, and flanking movements.

The Dahomey Amazons, a unit of all-female soldiers, were a very unusual part of the kingdom's military. Unlike other regional powers, Dahomey's military did not have a strong cavalry (like the Oyo empire) or naval power. This prevented them from expanding along the coast. From the 18th century, the state could get naval support from Kingdom of Ardra. Dahomey used Ardra's navy against the Epe in 1778 and Badagry in 1783.

The Amazons

The Dahomean state was famous for its female soldiers. Their exact beginnings are debated. They might have started as palace guards or as female hunting teams. They were organized around 1729 to make the army seem larger in battle, at first only carrying banners. The women reportedly fought so bravely that they became a permanent part of the army.

At first, these soldiers were criminals forced into service instead of being executed. Eventually, the group was so respected that King Ghezo ordered every family to send him their daughters. The strongest ones were chosen as soldiers. European reports noted that it took an Amazon 30 seconds to load a Dane gun, while it took a male Dahomean soldier 50 seconds.

Siege and Engineering Skills

To fight against the navies of its neighbors, Dahomey built causeways starting in 1774. During a campaign against Whydah that year, Dahomey forced Whydah to fortify itself on an island called Foudou-Cong. Dahomey cut trees and planted them in the water to create a causeway. This allowed the army to reach the fortified Whydah island. The causeway also blocked the movement of Whydah's 700 canoes. As a result, the Whydah army had to live on boats for months, eating only fish. Historian Thornton says Dahomey used this siege tactic again in 1776 against another enemy state. They built three bridges to connect to the island where the enemy forces were.

Coastal enemies of Dahomey allied with European forts against the state. Dahomey was able to capture Dutch and Portuguese forts in the 18th century using ladders and sappers (soldiers who dig tunnels). Thornton writes that in 1737, Dahomey used ladders against the Dutch fort in Keta. At the same time, its sappers dug a tunnel under the fort's bastion. This caused it to collapse when defenders fired a cannon inside. A similar tactic was used against a Portuguese fort with 30 cannons at Whydah in 1743. Its bastions collapsed, letting Dahomey's soldiers enter the fort. In 1728, Dahomey forces captured and destroyed a French fort at Whydah by blowing up its ammunition storage. Another tactic for attacking coastal forts was burning nearby villages during a land breeze. This allowed the wind to carry the flames toward the fort.

Because of the threat from Oyo in the 18th century, Dahomey built its own forts. They got help from a French officer who taught them about field fortification and artillery. A Dutch source in 1772 said the king of Dahomey "has made deep ditches around his entire country as well as walls and batteries mounted with cannons he captured at Fida [Whydah]." Thornton suggests these forts were mostly made of wood. Dahomey used a tactic of digging trenches against Oyo. Their forces would retreat into the trenches after fighting the Oyo army. Despite this, Oyo's siege overwhelmed Dahomey after reinforcements arrived. In the mid-18th century, Abomey was surrounded by a ditch with bridges. In 1772, the royal residence was surrounded by a mud brick wall 20 feet high, with "blockhouses on each wall."

Dahomey also built underground chambers in Abomey. These served various purposes, including military installations for the army. These underground areas date back to the late 17th century. Records show that wheeled vehicles were used in Dahomeyan warfare. In a fight against Abeokuta in 1864, Dahomey used three guns mounted on locally made carriages. Historian Robin Law adds that these weapons were not very effective in the battle. There are some mentions of guns and gunpowder possibly being made in Dahomey. In 1880, King Béhanzin told a French mission that firearms were made in the state. During the war with France in 1892, a French army found tools and resources needed for making cartridges and repairing firearms.

Dahomey's Economy

The kingdom's economy was closely linked to its political and religious systems. These systems grew together significantly. The main money used was cowry shells.

Local Economy

The local economy mainly focused on farming and crafts for people living in the kingdom. Until palm oil became important, very few farm goods or crafts were traded outside the kingdom. Markets played a key role in the kingdom. They were organized on a four-day cycle, with a different market each day. This market schedule was supported by religious beliefs.

Most farming was done by families in a decentralized way. As the kingdom grew, large farms became a common way to produce food. Craftwork was mostly controlled by a formal system of guilds. Some wealthy citizens stored their cowry shells in buildings called akueho (cowrie huts). These huts were designed to protect the cowries from fire and theft. Some historians suggest this was a form of banking in Dahomey. Owners of akueho houses often kept others' deposits, which they used as loans. However, other historians are unsure about this theory.

Taxes

Historian Herskovits describes a complex tax system in the kingdom. Officials, called tokpe, collected information from each village about their harvest. Then the king set a tax based on how much was produced and the village population. The king's own land and production were also taxed.

After the kingdom built many roads, toll booths were set up. These collected yearly taxes based on the goods people carried and their jobs. Officials sometimes also charged fines for public disturbances before letting people pass. Tax officials at road tolls had armed guards. Taxes were also placed on craft workers like blacksmiths, weavers, and wood cutters. Informal courts could be held anywhere, like in the market or on roads. Officials recognized by the government led these courts. Such courts could collect a type of tax from people involved in a case before judging it.

The Royal Road

An unpaved road system was built from the port of Ouidah through Cana up to Abomey. Its purpose was to make it easier for the king to travel between Cana and Abomey. The Royal Road dates back to the 18th century. However, most information about the road comes from the century after. The road stretched over seven miles in a nearly straight line, between the gates of the two towns. It was estimated to be 20–30 meters wide.

The road was regularly kept clear of weeds with cutlasses. Some sources say it was cleared every two or three months, or even every six weeks. Tall trees shaded the road. The biggest trees were a type of bombax. On both sides of the road were many farms. In the mid-19th century, Forbes said these farms "rivaled that of the Chinese."

Religious shrines were also placed along the road. Forbes counted 60 of them on the way to Abomey. A palace was built halfway along the road by Tegbesu (1740–1774). It served as a resting place for the king during travel. There is not much information about security on the Royal Road. Sources from the mid-19th century show that two large cannons were placed on each side of the road near Abomey, pointing toward Cana. Many cannons of different sizes were also placed at the road's end before the gates of Cana. Historian Alpern suggests that the cannons in front of Cana might have been for ceremonies because they lacked carriages to move them.

Trade of Captives

Both domestic slavery and the Atlantic slave trade were important to Dahomey's economy. Men, women, and children captured by Dahomey in wars and slave raids were sold to European traders. In return, Dahomey received goods like rifles, gunpowder, textiles, cowry shells, and alcohol. Dahomey used special rituals for this trade. Before being sold, captives were forced to walk in circles around the "Tree of Forgetfulness." This was meant to make them lose memories of their culture, family, and homeland. The goal was to prevent the spirits of deceased captives from returning to seek revenge on Dahomey's royalty.

Other war captives who were not sold to Europeans stayed in Dahomey as slaves. They worked on royal farms that provided food for the army and the royal court.

Dahomey's Religion

The Kingdom of Dahomey shared many religious practices with nearby groups. It also developed its own unique ceremonies, beliefs, and stories. These included worshipping royal ancestors and practicing West African Vodun.

Royal Ancestor Worship

Early kings made sure that royal ancestors were clearly worshipped. Their ceremonies were central to the Annual Customs of Dahomey. The spirits of the kings held a high place in the land of the dead. It was necessary to get their permission for many activities on Earth.

Ancestor worship existed before the Kingdom of Dahomey. Under King Agaja, a cycle of rituals was created. It focused first on celebrating the king's ancestors, then on celebrating family lineages. The Annual Customs of Dahomey (called xwetanu or huetanu in Fon) had many detailed parts. Some aspects may have been added in the 19th century. Generally, the celebration involved giving gifts, military parades, and political meetings. Its main religious purpose was to thank and get approval from the royal ancestors.

Beliefs about the Universe

Dahomey had a special form of West African Vodun. It combined older animist traditions with Vodun practices. Oral history says that Hwanjile, a wife of Agaja and mother of Tegbessou, brought Vodun to the kingdom and helped it spread. The main god is the combined Mawu-Lisa. Mawu has female traits, and Lisa has male traits. It is believed that this god took over the world created by their mother, Nana-Buluku. Mawu-Lisa rules the sky and is the highest group of gods. But other gods exist in the Earth and in thunder. Religious practice organized different priests and shrines for each god and each group of gods (sky, Earth, or thunder). Many women were priests, and the chief priest was always a descendant of Dakodonou.

Dahomey's Arts

The arts in Dahomey were unique and different from other artistic traditions in Africa. The king and his family greatly supported the arts. Dahomey had non-religious art traditions, used many different materials, and borrowed ideas from other peoples in the region. Common art forms included wood and ivory carving, metalwork (silver, iron, and brass), appliqué cloth, and clay bas-reliefs.

The king was key in supporting the arts. Many kings gave large amounts of money to artists. This led to the special development of non-religious art in the kingdom, which was unusual for the region. Artists were not from a specific social class. Both royalty and common people made important artistic contributions. Kings were often shown in large animal forms, with each king looking like a particular animal in many artworks.

Suzanne Blier points out two unique things about art in Dahomey: combining different parts and borrowing from other states. Combining art, which means putting many different parts (often of different materials) into one piece, was common in all forms. This happened because the kings promoted finished products rather than specific styles. This combining might have come from the second feature, which was borrowing many styles and techniques from other cultures and states. Clothing, cloth work, architecture, and other art forms all looked similar to other art from around the region.

Much of the artwork was about the royal family. Each of the palaces at the Royal Palaces of Abomey had detailed bas-reliefs (called noundidė in Fon). These showed a record of the king's achievements. Each king had his own palace within the palace complex. Inside the outer walls of their personal palace was a series of clay reliefs made specifically for that king. These were not only for royalty. Chiefs, temples, and other important buildings had similar reliefs. The reliefs often showed Dahomey kings in battles against the Oyo or Mahi tribes to the north. Their enemies were shown in negative ways (the king of Oyo is shown as a baboon eating corn). Historical themes were common, and characters were simply designed. They were often placed on top of each other or close together, creating a combined effect.

Besides royal depictions in reliefs, royal members were shown in power sculptures called bocio. These combined different materials like metal, wood, beads, cloth, fur, feathers, and bone onto a base, forming a standing figure. The bocio were designed for religious purposes to bring different forces together and unlock powerful energies. Also, the cloth appliqué of Dahomey often showed royalty in similar animal forms. These dealt with topics similar to the reliefs, often showing kings leading during warfare.

Dahomey had a distinct tradition of making small brass figures of animals or people. These were worn as jewelry or displayed in the homes of wealthier people. These figures, still made for tourists today, were unusual in traditional African art because they had no religious meaning. They were purely decorative and showed some wealth. Also unusual, because it is so old and clearly identified, is a carved wooden tray in Ulm, Germany. It was brought to Europe before 1659, when it was described in a printed catalog.

Wheeled carriages were used in Dahomey after they were brought to the region of modern Benin in the late 17th century. Some carriages were made locally, while most were gifts from European allies. The carriages were often used for ceremonies. Men usually pulled them because there were few horses in the state. Carriages in Dahomey came in different sizes and shapes. Some were shaped like ships, elephants, and horses. Burton noted that the road between Abomey and Cana, about six to seven miles long, was regularly kept clear for the royal carriages.

|

See also

In Spanish: Reino de Dahomey para niños

In Spanish: Reino de Dahomey para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |