Oyo Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Oyo Empire

Ilú-ọba Ọ̀yọ́ (Yoruba)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1300–1896 | |||||||

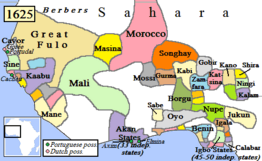

Oyo Empire during the 17th–18th centuries

|

|||||||

| Status | Empire | ||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||

| Common languages | Yoruba | ||||||

| Religion | Yoruba religion, Islam, Christianity | ||||||

| Government | Elective Monarchy | ||||||

| Alaafin | |||||||

|

• c. 1300

|

Oranmiyan | ||||||

|

• ????–1896

|

Adeyemi I Alowolodu | ||||||

| Legislature | Oyo Mesi and Ogboni | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| 1680 | 150,000 km2 (58,000 sq mi) | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Today part of | Yorubaland · Nigeria · Benin | ||||||

| House of Oranyan |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent House: | Oodua | ||

| Titles: | * Oba Alaafin of Oyo

|

||

| Founder: | Oranyan | ||

| Current Head: | Adeyemi III | ||

| Cadet Branches: | * Alowolodu (Oyo) |

||

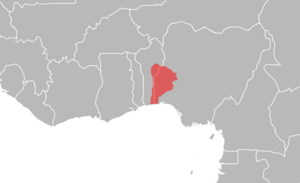

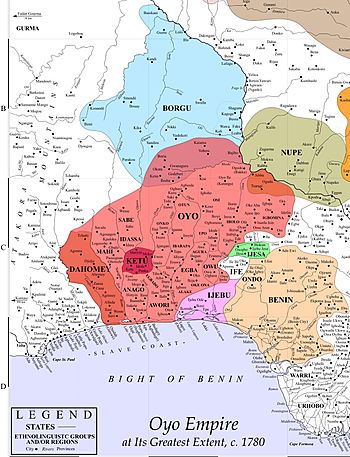

The Oyo Empire was a powerful Yoruba empire in West Africa. It included parts of what is now eastern Benin and western Nigeria. It grew to be the largest Yoruba-speaking state. The empire became strong because of the Yoruba people's great organization, wealth from trade, and a powerful army that used horses (cavalry).

From the mid-1600s to the late 1700s, the Oyo Empire was one of the most important states in Western Africa. It controlled most other kingdoms in Yorubaland. It also had power over nearby African states, like the Fon Kingdom of Dahomey in modern Benin.

Contents

History of the Oyo Empire

How the Empire Began

The Oyo Empire's story starts with Oranyan, a prince from the Yoruba Kingdom of Ile-Ife. Oranyan and his brother planned to attack their northern neighbors. But they argued, and their army split up. Oranyan's group was too small, so he traveled south until he reached Bussa.

A local chief there gave Oranyan a magical snake. The chief told him to follow the snake until it stopped for seven days and disappeared into the ground. Oranyan followed this advice and founded Oyo where the snake stopped. This place is now called Ajaka. Oranyan became the first ruler, known as the "Alaafin of Oyo". "Alaafin" means 'owner of the palace' in Yoruba.

Early Years and Challenges (12th Century–1535)

Oranyan was followed by Oba Ajaka as Alaafin. Ajaka was removed from power because he was not seen as a strong military leader. His brother, Shango, took over. Shango later became known as the god of thunder and lightning. After Shango's death, Ajaka returned to the throne, now much more warlike. His successor, Kori, conquered the rest of the main Oyo area.

The capital of Oyo was called Oyo-Ile, also known as Old Oyo. The most important buildings were the 'Afin' (the Oba's palace) and the 'Oja-Oba' (the Oba's market). An enormous earthen wall with 17 gates protected the city.

By the late 1300s, Oyo was a strong inland power. But around 1535, the Nupe attacked Oyo. They forced the Oyo rulers to flee to the kingdom of Borgu. The Nupe destroyed the capital, stopping Oyo from being a major power until the early 1600s.

Rise of the Empire (1608–1800)

After being exiled for about 80 years, the Yoruba people of Oyo rebuilt their empire. They made it more organized and powerful than before. They created a government that ruled over a huge area. During the 1600s, Oyo grew into a major empire. It became the most populated kingdom in Yoruba history, though it did not include all Yoruba-speaking people.

Reconquering and Expanding Territory

To rebuild Oyo, the Yoruba created a stronger military and a more central government. They learned from their Nupe enemies and started using armor and cavalry (soldiers on horseback). Oba Ofinran, the Alaafin of Oyo, took back Oyo's original land from the Nupe. A new capital, Oyo-Igboho, was built.

The next Oba, Eguguojo, conquered almost all of Yorubaland. After him, Oba Orompoto led attacks to completely defeat the Nupe. This made sure Oyo was safe from them. Under Oba Ajiboyede, the first Bere festival was held. This event celebrated peace in the kingdom and remained important for a long time.

Under Oba Abipa, the Yoruba people moved back to and rebuilt the original capital, Oyo-Ile. Oyo continued to expand, even after failing to conquer the Benin Empire. By the end of the 1500s, the Ewe and Aja states in modern Benin were paying taxes to Oyo.

Conquering Dahomey

The Oyo Empire started raiding south in 1682. Its borders eventually reached the coast, about 100 kilometers southwest of its capital. It faced little resistance until the early 1700s. In 1728, the Oyo Empire invaded the Kingdom of Dahomey with its cavalry. Dahomey warriors had no cavalry but used many firearms. Their gunshots scared the Oyo horses. Dahomey also built trenches, forcing the Oyo army to fight on foot. The battle lasted four days, but Oyo won after more soldiers arrived. Dahomey had to pay tribute to Oyo. The Yoruba invaded Dahomey 11 times before finally taking control of the small kingdom in 1748.

Later Military Successes

Oyo's cavalry helped it win battles and control distant lands. The Oyo army could attack strong defenses. However, it was hard to supply the army, so they would leave when supplies ran out. Oyo did not use guns in its main conquests until the 1800s. In 1764, a combined force of Akan, Dahomey, and Oyo soldiers defeated an Asante army. This victory set the borders between these states. Oyo also led a successful campaign into Mahi territory north of Dahomey in the late 1700s. Oyo also used soldiers from the kingdoms it controlled. For example, in 1784, an Oyo-Dahomey-Lagos force blocked the port of Badagri by sea.

How the Empire Was Organized

As the empire grew, Oyo changed its structure to manage its vast lands better. It was divided into four main parts, based on how close they were to the empire's center. These were Metropolitan Oyo, southern Yorubaland, the Egbado Corridor, and Ajaland.

- Metropolitan Oyo

This was the heart of the empire, where the Yoruba spoke the Oyo dialect. It was divided into six provinces, with three on each side of the Ogun River. Each province had a governor chosen by the Alaafin of Oyo.

- Southern Yorubaland

This second part of the empire included towns closer to Oyo-Ile. Their Yoruba people spoke different dialects. These states had their own rulers, called Obas, but the Alaafin of Oyo had to approve them.

- Egbado Corridor

This third part was southwest of Yorubaland. It was home to the Egba and Egbado people. This area was important for Oyo's trade with the coast. These groups ruled themselves but were watched by Ajele. These were agents sent by the Alaafin to look after his interests and check on trade.

- Ajaland

Ajaland was the newest and most distant part of the empire. It was kept in line by threats of military attacks. This area stretched from non-Yoruba lands west of the Egbado Corridor into Ewe territory in modern Togo. Like other controlled states, it had some freedom as long as it paid taxes, followed Oyo's orders, and allowed Oyo merchants to trade. Oyo often demanded slaves as tribute. Sometimes, local chiefs would fight others to capture slaves for this purpose. Oyo was known to punish disobedience severely, like in Allada in 1698.

How the Government Worked

The Oyo Empire had a very complex government. After returning from exile in the early 1600s, Oyo became more focused on military power. The way the king (Oba) and his council worked showed this aggressive Yoruba culture.

The Alaafin of Oyo

The Oba of Oyo, called the Alaafin of Oyo, was the empire's supreme leader. He was responsible for protecting his people from attacks. He also settled arguments between local rulers and helped them with their people. The Alaafin was expected to give gifts and honors to his subordinates. In return, all local rulers had to show respect and loyalty to the Oba each year. The most important event was the Bere festival, which celebrated the Alaafin's successful rule. After this festival, peace was supposed to last for three years.

The king could not be removed from power, but he could be forced to end his own life if he was no longer wanted. This happened if the Bashorun (the prime minister) gave him an empty calabash or a dish of parrot's eggs. This was a sign that "the people, the world, and the gods reject you." The Alaafin was then expected to die by his own hand.

Choosing the Alaafin

The Oyo Empire was not a simple hereditary monarchy. The Alaafin was chosen by the Oyo Mesi council. He did not always have to be closely related to the previous king. However, he had to be a descendant of Oranmiyan and come from the Ona Isokun royal family.

In the early empire, the Alaafin's oldest son, known as the Aremo, usually took over. This sometimes led the Aremo to try to speed up his father's death. To stop this, it became a tradition for the Aremo to die when his father died. Even without becoming king, the Aremo was very powerful. The Alaafin rarely left the palace, except for important festivals. But the Aremo often left the palace. This led historian S. Johnson to say: "The father is the king of the palace, and the son the king for the general public." The two councils that limited the Alaafin's power often chose a weak Alaafin after a strong one. This helped keep the king from becoming too powerful.

The Ilari Officials

The Alaafin of Oyo appointed special religious and government officials called the ilari. These officials were known as "half-heads" because they shaved half of their heads. There were hundreds of Ilari, both men and women. Younger Ilari did simple tasks, while older ones acted as guards or messengers. Their titles often related to the king, like oba l'olu ("the king is supreme"). They carried red and green fans to show their rank.

All local courts in Oyo had Ilari. They acted as spies and tax collectors. Oyo sent them to Dahomey and the Egbado Corridor to collect taxes and gather information on Dahomey's military.

The Councils that Checked the King's Power

Even though the Alaafin of Oyo was the supreme leader, his power was not absolute. The Oyo Mesi council and the Yoruba Earth cult called Ogboni kept the Oba's power in check. The Oyo Mesi spoke for the politicians, while the Ogboni spoke for the people and had religious authority. The Alaafin's power depended on his own personality and political skills.

Oyo Mesi Council

The Oyo Mesi were seven main advisors to the state. They chose the Alaafin and had law-making powers. The Bashorun, who was like the prime minister, led them. The Oyo Mesi also included the Agbaakin, Samu, Alapini, Laguna, Akiniku, and Ashipa. They represented the people's voice and were responsible for protecting the empire's interests. The Alaafin had to ask for their advice on important state matters. Each chief had daily duties at court. They also had deputies they could send if they couldn't be there. The Oyo Mesi limited the Alaafin's power, stopping him from being an absolute ruler. They forced many Alaafins to end their own lives in the 1600s and 1700s.

The Bashorun, head of the Oyo Mesi, consulted the Ifa oracle before a new king was chosen. This was to get approval from the gods. New Alaafins were seen as chosen by the gods, called Ekeji Orisa ("deputy of the gods"). The Bashorun had the final say on who became the new Alaafin, and his power was almost equal to the king's. For example, the Bashorun organized many religious festivals. He was also the commander-in-chief of the army, giving him much religious and military power.

One of the Bashorun's most important duties was the Orun festival. This religious event, held every year, decided if the Mesi members still supported the Alaafin. If the council decided they no longer approved of the Alaafin, the Bashorun would give the Alaafin an empty calabash or parrot's eggs. This was a sign that the king must die. This was the only way to remove an Alaafin, as he could not be legally removed from his position. Once given the calabash or eggs, the Alaafin, his oldest son (the Aremo), and his personal advisor (the Asamu) all had to die to renew the government.

The Ogboni Society

The Oyo Mesi did not have absolute power either. While the Oyo Mesi had political influence, the Ogboni represented the people's views, supported by religious authority. So, the Ogboni could balance the Oyo Mesi's decisions. This system of checks and balances meant no one person had total power.

The Ogboni was a very powerful secret society. It was made up of older, wise, and important free men. They had great power over common people because of their religious standing. There were (and still are) Ogboni councils in almost all local courts in Yorubaland. Besides their duties related to earth worship, they judged any case involving bloodshed. The leader of the Ogboni, the Oluwo, could speak directly to the Alaafin of Oyo about any matter.

Oyo's Military Might

The Oyo Empire had a very professional army. Its military success came from its cavalry (soldiers on horseback), and the strong leadership of its officers and warriors. Because most of Oyo's land was in the northern valley, farming was easier, leading to a steady growth in population. This helped Oyo always have a large army. There was also a strong military culture in Oyo where winning was a must. Losing often meant a general had to end their own life. This "do-or-die" policy likely made Oyo's generals very aggressive.

Cavalry (Horse Soldiers)

The Oyo Empire was one of the few Yoruba states to use cavalry. This was because most of its territory was in the northern valley. Other nearby groups like the Nupe, Borgu, and Hausa also used cavalry. Oyo could buy horses from the north and keep them in its main territory because there were fewer tsetse flies there.

Cavalry was the main force of the Oyo Empire. In the late 1500s and 1600s, military expeditions were made up entirely of cavalry. However, there were limits. Oyo could not keep its cavalry army in the southern, forested areas, but they could raid those areas easily.

Oyo's cavalry had two types: light and heavy. Heavy cavalry rode larger imported horses and used long spears or lances and swords. Light cavalry rode smaller local ponies and used clubs or bows.

Infantry (Foot Soldiers)

Foot soldiers in the Oyo Empire and nearby areas had similar armor and weapons. All infantry carried shields, swords, and lances. Shields were about four feet tall and two feet wide, made from elephant or ox hide. A nine-foot-long heavy sword was the main weapon for close fighting. The Yoruba and their neighbors also used javelins (light spears) with three barbs, which could be thrown accurately from about 100 paces.

Military Structure

The Oyo Empire used both local and allied forces to expand its control. Before its imperial period, the Oyo military was simpler and more directly controlled by the central government. This worked when Oyo only controlled its heartland in the 1400s. But to conquer and hold distant lands, the military structure changed.

The Eso Warriors

Oyo had a semi-permanent army of special cavalry soldiers called the Eso, or Eso of Ikoyi. These were 70 junior war chiefs chosen by the Oyo Mesi and approved by the Alaafin. The Eso were chosen for their military skill, not their family background. They were led by the Are-Ona-Kakanfo and were known for living by a strict warrior code.

Are-Ona-Kakanfo (Supreme Commander)

After Oyo returned from exile, the position of Are-Ona-Kakanfo was created as the supreme military commander. He had to live in an important border area to watch the enemy and prevent him from trying to take the throne. During Oyo's imperial period, the Are-Ona-Kakanfo personally led the army in all campaigns.

Metropolitan Army

Since the Are-Ona-Kakanfo could not live near the capital, plans were made to protect it in emergencies. Forces inside the main Oyo area were commanded by the Bashorun, the leading member of the Oyo Mesi. As mentioned, Metropolitan Oyo was divided into six provinces by a river. So, provincial forces were grouped into two armies, led by the Onikoyi for the east side of the river and the Okere for the west side. Lesser war chiefs were called Balogun.

Tributary Army

Leaders of controlled states and provincial governors were responsible for collecting taxes and providing troops to the imperial army when needed. Sometimes, these leaders were ordered to attack neighbors even without the main imperial army's help. These forces were often used in Oyo's distant campaigns, like on the coast or against other states.

Trade and Wealth

Oyo became the main trading center in the south for the Trans-Saharan trade route. Goods like salt, leather, horses, kola nuts, ivory, cloth, and slaves were traded. The Yoruba people in the main Oyo area were also very skilled in crafts and iron work. Besides taxes on trade goods, Oyo also became rich from taxes on the states it controlled. Taxes from the kingdom of Dahomey alone brought in about 1 million US dollars a year.

The Empire's Peak

By 1680, the Oyo Empire covered over 150,000 square kilometers. It reached its greatest power in the 1700s. Even though it was created through conflict, it stayed together because everyone benefited. The government brought unity to a large area by allowing local areas some freedom while keeping imperial authority.

Unlike other large empires in the savannah, the Oyo Empire had very little Islamic influence. However, some Muslim officials were known to be in the main Oyo area. French traders in 1787 reported seeing men who could write and calculate in Arabic.

Decline of the Empire

Many believe the Oyo Empire started to decline as early as 1754. This was due to power struggles and palace takeovers led by the Oyo Prime Minister, Gaha. Gaha wanted total power. He worked with the Oyo Mesi and possibly the Ogboni to force four Alaafins to die after being given the symbolic parrot's eggs. Between June and October 1754 alone, two Alaafins were forced to end their lives by Gaha. Because of this, Alaafin Awonbioju ruled for only 130 days, and Alaafin Labisi for only 17 days. Gaha's actions finally ended in 1774 during the reign of Alaafin Abiodun, the fifth Alaafin he served. Abiodun had Gaha executed, but these power struggles had already weakened Oyo.

During his reign, Alaafin Abiodun also led failed campaigns against Borgu in 1783 and Nupe in 1789. He lost many generals and their soldiers in these battles. Abiodun was later killed by his own son, Awole, who then became king.

The events that led to Ilorin breaking away began in 1793. Ilorin was a military camp led by the Are-Ona Kakanfo, Afonja. Afonja disagreed with Awole when the king ordered him to attack Iwere-Ile, which was Alaafin Abiodun's mother's hometown. Afonja refused because he had sworn an oath and did not want to be cursed. Another reason for conflict came in 1795 when Awole ordered Afonja to attack Apomu, a market town in Ile-Ife. All Alaafins had previously sworn an oath never to attack Ife, as it was seen as the spiritual home of the Yorubas. Afonja attacked Apomu, but when the army returned, he marched on the capital, Oyo-Ile (which was forbidden). He demanded that Awole step down. Awole eventually died.

After Awole's death, many people fought for the throne. Some kings ruled for less than six months. There was also a period of almost twenty years when no one could agree on a new king. This lack of a strong leader allowed powerful military and regional commanders to rise. Shehu Alimi, a Fulani chief and leader of the growing Muslim population in Oyo, also gained power. These new leaders no longer respected the Alaafin's position due to the political problems and lack of central authority. This led to Afonja separating Ilorin from Oyo in 1817, with the help of Oyo Muslims. In 1823, after Afonja was killed by his former allies, Ilorin became part of the Sokoto Caliphate. By the time Captain Hugh Clapperton visited Oyo-Ile in 1825, the empire was already in decline. Clapperton saw many Oyo villages burned by the Fulani of Ilorin. The Oyo also had a shortage of horses, even though they were known for their cavalry.

Ilorin then attacked Offa and began raiding and burning villages in Oyo. They finally destroyed the capital, Oyo-Ile, in 1835.

Losing the Egbado Corridor

As Oyo was weakened by internal conflicts, its controlled states started seeking independence. The Egba people, led by a war chief named Lishabi, killed the Ilari officials in their area and drove off an Oyo army sent to punish them.

Dahomey's Rebellion

In 1823, Dahomey raided villages that Oyo was supposed to protect. Oyo immediately demanded a huge payment from King Gezo for this attack. Gezo sent his Brazilian representative to the Alaafin to make peace. The peace talks failed, and Oyo attacked Dahomey. However, the Oyo army was completely defeated, ending Oyo's control over Dahomey. After gaining its freedom, Dahomey began raiding the Egbado Corridor.

Moving the Capital to Ago d'Oyo

After Oyo-Ile was destroyed, the capital was moved further south to Ago d'Oyo. Oba Atiba tried to save what was left of Oyo. He gave Ibadan the job of protecting the capital from Ilorin in the north. He also tried to get Ijaye to protect Oyo from the west against the Dahomeans. However, the center of Yoruba power shifted further south to Ibadan, a war camp settled by Oyo commanders in 1830.

The Final End

Atiba's efforts failed, and Oyo never regained its importance in the region. The Oba, Atiba Atobatele, died in 1859. His son Adeyemi I, the third Alaafin to rule in the current Oyo, died in 1905. During the colonial period, the Yorubas were one of the most urbanized groups in Africa. About 22% of the population lived in large cities with over 100,000 people. Over 50% lived in cities of 25,000 or more. The Yoruba continue to be the most urbanized African ethnic group today. Important modern cities include Oyo, Ibadan, Osogbo, and Ogbomoso. These cities grew after the fall of Old Oyo.

A small part of the monarchy still exists today as one of the traditional states of modern Nigeria.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Imperio oyo para niños

In Spanish: Imperio oyo para niños