Independence of Brazil facts for kids

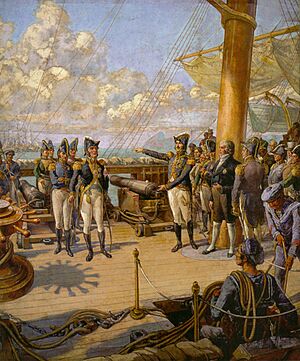

| Part of the War of Independence of Brazil | |

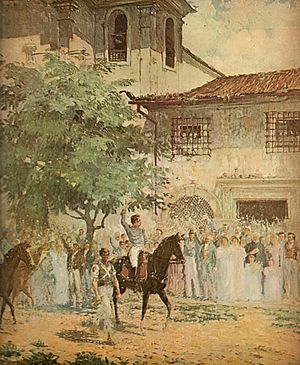

Declaration of Brazil's independence by Prince Pedro, regent on 7 September 1822. His Guard of Honor greets him in support while some discard blue and white armbands that represented loyalty to Portugal. Painting Independence or Death by Pedro Américo.

|

|

| Date | 7 September 1822 |

|---|---|

| Location | São Paulo and Bahia, Brazil |

| Participants | Pedro, Prince Royal Archduchess Maria Leopoldina José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva |

| Outcome | Independence of the Kingdom of Brazil from the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves and subsequent formation of the Empire of Brazil under Emperor Dom Pedro I (1798–1834; reigned 1822–1831) |

The independence of Brazil was a series of important events that led to Brazil becoming a country separate from Portugal. Before this, Brazil was part of the "United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves." Most of these events happened in places like Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo between 1821 and 1824.

Brazil celebrates its Independence Day on September 7. This date marks when Prince Dom Pedro declared Brazil's independence in 1822. However, some people believe the real independence happened later, after a big fight called the Siege of Salvador on July 2, 1823, in Salvador. Portugal officially recognized Brazil's independence three years later, in a treaty signed in late 1825.

Contents

Background: How Brazil Began

The land we now call Brazil was claimed by Portugal in April 1500. This happened when a Portuguese fleet, led by Pedro Álvares Cabral, arrived. They met many different Indigenous tribes who spoke similar languages and shared the land.

However, the Portuguese brought diseases like measles and smallpox. Many Indigenous people had no protection against these illnesses, and tens of thousands died.

The first Portuguese settlement was built in 1532. But real colonization started in 1534 when King John III divided the land. He created fifteen "captaincies," which were like large areas ruled by families. This system didn't work well. So, in 1549, the king appointed a Governor-General to manage the whole colony. Some native tribes joined the Portuguese, while others disappeared due to wars or diseases.

By the mid-1500s, sugar became Brazil's most important export. To make more money, over 963,000 African slaves were brought to Brazil by 1700. They were forced to work on sugar plantations. More enslaved Africans came to Brazil than to all other places in the Americas combined.

The Portuguese slowly expanded their territory through wars. They took Rio de Janeiro in 1567 and São Luís in 1615. They also explored the Amazon River basin, building villages and forts. By 1680, they reached the far southeast and founded Colônia do Sacramento in what is now Uruguay.

At the end of the 1600s, sugar exports started to drop. But in the 1690s, explorers found gold in areas like Minas Gerais. This discovery saved the colony from collapse. Thousands of people, from Brazil and Portugal, rushed to the mines.

Spain tried to stop Portugal from expanding into lands they claimed. These lands were given to Spain by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. However, a new agreement in 1777, the Treaty of San Ildefonso, confirmed Portugal's right to the lands it had expanded into. This created most of Brazil's current southeastern border.

In 1807, Napoleon I invaded Portugal. The Portuguese royal family, with help from the British Royal Navy, fled across the Atlantic to Brazil. Rio de Janeiro became the temporary capital of the Portuguese Empire. This move helped Brazil because it started to develop its own government and could trade with other countries more freely.

After Napoleon was defeated in 1815, King John VI of Portugal wanted to keep the capital in Brazil. To calm fears that Brazil would become just a colony again, he made Brazil an equal "kingdom." It became an official part of the "United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves." He sent his son, Dom Pedro, to govern Brazil as prince regent.

Path to Independence

Portuguese Cortes and Growing Tensions

In 1820, a revolution started in Portugal. People wanted a new constitution for the kingdom. This led to a meeting called the Cortes (an assembly). The Cortes demanded that King John VI return to Portugal. He had been living in Brazil since 1808.

The King left Brazil on April 26, 1821. He left his son, Prince Dom Pedro, in charge of Brazil. Pedro governed with the help of his ministers.

Portuguese military officers in Brazil supported the revolution in Portugal. Their leader, General Jorge de Avilez Zuzarte de Sousa Tavares, forced Prince Pedro to fire his loyal ministers. Pedro felt humiliated and promised he would never let the military control him again. This event greatly influenced his future decisions.

On September 30, 1821, the Cortes decided that Brazil's provinces would be directly controlled by Portugal. Prince Pedro became only the governor of Rio de Janeiro Province. Other orders from the Cortes told him to return to Europe and closed down courts that King John VI had created in Brazil.

Many people in Brazil, both Brazilians and Portuguese living there, were unhappy with these decisions. Two main groups formed to oppose the Cortes:

- The Liberals, led by Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo, wanted Brazil to have its own assembly.

- The Bonifacians, led by José Bonifácio de Andrada, wanted Pedro to create the constitution himself.

Both groups agreed that Brazil should remain a kingdom, equal to Portugal, not just a group of provinces controlled from Lisbon.

Pedro's Decision to Stay

The Portuguese members of the Cortes showed no respect for Prince Pedro. They openly made fun of him. Because of this, Pedro's loyalty to the Cortes slowly changed. He started to support the Brazilian cause. His wife, Princess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, also encouraged him to stay in Brazil.

On January 9, 1822, Pedro made his famous decision. He said: "As it is for the good of all and for the nation's general happiness, I am ready: Tell the people that I will stay." This day is known as "Dia do Fico" (I Will Stay Day).

After Pedro decided to stay, about 2,000 men led by Jorge Avilez rebelled. They gathered on Mount Castelo but were soon surrounded by 10,000 armed Brazilians. Prince Pedro then ordered Avilez and his soldiers to leave Brazil.

José Bonifácio was made minister of Kingdom and Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1822. He became a close advisor to Pedro. The Liberals wanted to reduce Bonifácio's influence. They offered Pedro the title of "Perpetual Defender of Brazil." The Liberals also wanted a special assembly to write a Brazilian constitution. The Bonifacians preferred that Pedro write the constitution himself to avoid chaos.

Pedro agreed with the Liberals. On June 3, 1822, he signed a decree calling for elections. This would create a "Constituent and Legislative General Assembly" in Brazil.

From United Kingdom to Independent Empire

Pedro traveled to São Paulo Province to make sure the region was loyal to the Brazilian cause. He arrived on August 25 and stayed until September 5. On his way back to Rio de Janeiro on September 7, he received important letters. These letters were from José Bonifácio and his wife, Leopoldina.

The letters told him that the Cortes had canceled all of Bonifácio's decisions. They had also taken away Pedro's remaining powers and ordered him to return to Portugal. It was clear that independence was the only choice left, and his wife supported it.

Pedro turned to his companions, including his Guard of Honor. He said: "Friends, the Portuguese Cortes want to enslave and pursue us. From today on our relations are broken. No ties can unite us anymore." He took off his blue-white armband, which symbolized Portugal. He declared: "Armbands off, soldiers. Hail to the independence, to freedom and to the separation of Brazil from Portugal!" He then drew his sword and swore: "For my blood, my honor, my God, I swear to give Brazil freedom." Finally, he cried out: "Brazilians, Independence or death!" This famous moment is known as the "Cry of Ipiranga."

Returning to the city of São Paulo that night, Pedro and his companions announced Brazil's independence from Portugal. People celebrated widely and called Pedro not just "King of Brazil," but also "Emperor of Brazil."

Pedro returned to Rio de Janeiro on September 14. In the following days, the Liberals spread flyers suggesting that Pedro should be named "Constitutional Emperor." On September 17, the head of the Rio de Janeiro city council, José Clemente Pereira, announced that Pedro would be celebrated as Emperor on October 12, his birthday.

The official separation from Portugal happened on September 22, 1822. Pedro wrote a letter to João VI, still calling himself Prince Regent. He considered his father the King of an independent Brazil. On October 12, 1822, Prince Pedro was celebrated as Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil. This marked the beginning of his rule and the start of the Empire of Brazil. Pedro said that if his father returned to Brazil, he would step down from the throne for him.

The title of "emperor" was chosen because "king" might suggest a continuation of the old Portuguese rule. "Emperor" came from popular support, like in Ancient Rome or with Napoleon. On December 1, 1822, Pedro I was officially crowned.

International Recognition

The first country to recognize Brazil's independence was the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (now Argentina) in June 1823. The United States followed in May 1824, and the Kingdom of Benin in July 1824. Some historians also say that the African states of Dahomey and Onim recognized Brazil even earlier, in 1822 and 1823. These African states had strong ties with South America.

War of Independence

After Brazil declared independence, the new government only controlled Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and nearby areas. The rest of Brazil was still controlled by Portuguese groups and soldiers. A war was needed to bring all of Brazil under Pedro's control. Fighting started in 1822 and continued until January 1824, when the last Portuguese soldiers left the country.

The new Brazilian government had to create its own Army and Navy. Many people, including foreign immigrants, were forced to join. Brazil also used enslaved people in its militias, sometimes freeing them to join the army and navy. The battles took place across large areas, including Bahia, Cisplatina, Grão-Pará, Maranhão, Pernambuco, Ceará, and Piauí.

By 1822, Brazilian forces controlled Rio de Janeiro and central Brazil. However, strong Portuguese forces in port cities like Salvador, Montevideo, São Luís, and Belém still controlled their surrounding areas. These forces posed a threat of reconquest. The Brazilian militias and guerrilla fighters, who were surrounding these cities, needed more help.

To break this stalemate, Brazil needed to control the sea. Eleven former Portuguese warships in Rio de Janeiro became the start of the new Brazilian navy. The problem was finding enough loyal sailors. Many of the ships' crews were Portuguese and not loyal to Brazil. The Brazilian government secretly hired 50 officers and 500 sailors in London and Liverpool. Many of these were experienced soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars. Thomas Cochrane was appointed as the commander-in-chief.

On April 1, 1823, a Brazilian fleet of 6 ships sailed to Bahia. After a difficult first battle with a larger Portuguese fleet, Cochrane blocked the port of Salvador. Without supplies or reinforcements by sea, and surrounded by the Brazilian army on land, the Portuguese forces left Bahia on July 2 in a convoy of 90 ships.

Cochrane then sailed north to São Luís (Maranhão). There, he tricked the Portuguese soldiers into leaving Maranhão. He pretended that a huge Brazilian fleet and army were about to arrive. He then sent Captain John Pascoe Grenfell to do the same trick in Belém do Pará, at the mouth of the Amazon River. By November 1823, all of northern Brazil was under Brazilian control. The next month, the Portuguese also left Montevideo and the Cisplatine Province. By 1824, Brazil was free of all enemy troops and was truly independent.

There are no exact numbers for how many people died in the war. But based on historical records and reports, and considering the war lasted 22 months, it's estimated that around 5,700 to 6,200 people were killed on both sides.

Peace Treaty and Aftermath

The last Portuguese soldiers left Brazil in 1824. The Treaty of Rio de Janeiro, which officially recognized Brazil's independence, was signed by Brazil and Portugal on August 29, 1825.

Brazil became independent with relatively little fighting and disruption. However, this meant that Brazil kept its old social structure from colonial times. This included having a monarchy, slavery, large land estates, and a society where most people could not read or write.

See also

In Spanish: Independencia de Brasil para niños

In Spanish: Independencia de Brasil para niños

- Empire of Brazil

- Colonial Brazil

- Cry of Ipiranga

- History of Brazil

- Treaty of Rio de Janeiro (1825)

- Independence Day (Brazil)

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |