Maria Leopoldina of Austria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Maria Leopoldina of Austria |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Joseph Kreutzinger, c. 1815

|

|||||

| Empress consort of Brazil | |||||

| Tenure | 12 October 1822 – 11 December 1826 | ||||

| Queen consort of Portugal | |||||

| Tenure | 10 March 1826 – 2 May 1826 | ||||

| Born | 22 January 1797 Hofburg, Vienna, Archduchy of Austria, Holy Roman Empire |

||||

| Died | 11 December 1826 (aged 29) Palace of Saint Christopher, Rio de Janeiro, Empire of Brazil |

||||

| Burial |

|

||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| Father | Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Dona Maria Leopoldina of Austria (born 22 January 1797 – died 11 December 1826) was the first Empress of Brazil. She was married to Emperor Dom Pedro I. She was Empress from October 12, 1822, until her death. She was also Queen of Portugal for a short time in 1826, when her husband was King Dom Pedro IV.

Maria Leopoldina was born in Vienna, Austria. Her father was Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. Her mother was Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily. She had many siblings, including Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria and Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, who was married to Napoleon Bonaparte.

She received a very good education, which was broad and included many subjects. The Habsburg family believed that children should learn good qualities like kindness and compassion. Maria Leopoldina had strong Christian faith and a good understanding of science, culture, and politics. She was prepared from a young age to be a proper royal wife.

Some historians believe she was very important in Brazil becoming independent in 1822. Her biographer, Paulo Rezzutti, says that Brazil became a nation largely thanks to her. He says she "embraced Brazil as her country, Brazilians as her people and Independence as her cause." She also advised Dom Pedro on big political choices. She is seen as the first woman to be a head of state in an independent American country.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Maria Leopoldina was born on January 22, 1797, at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Archduchy of Austria. She was the sixth child of Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor. Her mother was Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily. Her family, the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, was one of the oldest and most powerful royal families in Europe.

She was given the full name Caroline Josepha Leopoldine Franziska Ferdinanda. The name "Maria" was not in her baptism record. However, she started using it later, especially when she traveled to Brazil. Some believe she used "Maria" because of her strong devotion to the Virgin Mary.

Maria Leopoldina was born during a time of big changes in Europe. Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor of France and started many wars. Austria was often at war with France. Her older sister, Maria Ludovika, even married Napoleon in 1810 to try and make peace between France and Austria.

Her Education and Interests

When Maria Leopoldina was 10, her mother passed away. A year later, her father married Maria Ludovika of Austria-Este. Maria Ludovika was very well-educated and loved literature, nature, and music. She became a very important person in Maria Leopoldina's life and helped her develop these interests. Maria Leopoldina always saw her stepmother as a "spiritual mother."

Maria Leopoldina was raised with three main principles: discipline, religious devotion, and a sense of duty. Her childhood involved strict education and many cultural activities. She learned to put the needs of the state before her own desires. Her studies included reading, writing, dance, drawing, painting, piano, history, geography, and music. She also studied advanced subjects like math, literature, and physics.

She especially loved natural sciences, like botany (the study of plants) and mineralogy (the study of minerals). She collected coins, plants, flowers, minerals, and shells. She was also a talented polyglot, meaning she spoke many languages. She learned Portuguese very quickly in 1816 and could speak it fluently in just a few months. She also spoke German, French, Italian, English, Greek, and Latin.

She and her siblings often visited museums, botanical gardens, and factories. They also performed in plays and played instruments to get used to public events.

Marriage and Journey to Brazil

A Royal Alliance

Royal marriages in Europe were often about politics and creating alliances between countries. Maria Leopoldina's marriage to Dom Pedro de Alcântara, the Prince Royal of Portugal, was a strategic alliance between Portugal and Austria.

In 1816, Emperor Francis I announced that Dom Pedro wanted to marry a Habsburg princess. Maria Leopoldina was chosen. The marriage contract was signed in Vienna on November 29, 1816.

Maria Leopoldina prepared for her new life by studying the history and geography of Brazil and learning Portuguese. She also put together a special document with important information, which was unique for a Habsburg princess.

Her marriage to Dom Pedro happened by proxy (meaning someone stood in for Dom Pedro) on May 13, 1817, in Vienna. Her uncle, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, represented the groom.

This marriage was a political move. Portugal wanted new alliances, and Austria saw Brazil as an important partner. It was not based on love.

Journey to the New World

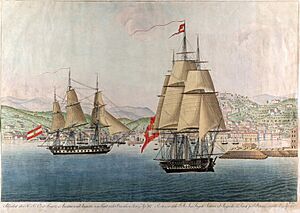

Maria Leopoldina's journey to Brazil was long and difficult. She left Vienna on June 2, 1817, and sailed from Livorno, Italy, on August 13, 1817. She traveled with many belongings, including 40 boxes of clothes, books, and collections. She also brought a large group of people, including ladies-in-waiting, guards, a doctor, and scientists. The trip across the Atlantic Ocean took 86 days. Her first stop in Portuguese territory was Madeira Island on September 11.

On November 5, 1817, Maria Leopoldina arrived in Rio de Janeiro. She finally met her husband and his family. The official wedding ceremony took place the next day at the Royal Chapel in Rio de Janeiro.

When she arrived, people were surprised by her appearance. However, she was very cultured and interested in botany. Her arrival gave the artist Jean-Baptiste Debret his first big job: decorating the city for the celebrations. Debret also designed the court uniforms and the new symbols for Brazil, like the Order of the Southern Cross.

Dom Pedro was a year younger than Maria Leopoldina. He was impulsive and not as well-educated as she was. He spoke little French, and his Portuguese was not refined. He also had other relationships, which made their marriage difficult from the start.

The young couple lived in relatively small rooms at the Palace of São Cristóvão. The palace grounds were often muddy, and there were many insects. The heat and humidity caused their clothes to rot. A diplomat noted that Dom Pedro lacked formal education and that the court in Rio was "boring and insignificant" compared to European courts.

Maria Leopoldina's arrival also led to the first wave of European immigrants to Brazil. Swiss settlers founded Nova Friburgo, and later, German immigrants settled in southern Brazil, creating places like São Leopoldo.

The Austrian Scientific Mission

Brazil was studied by European artists and scientists much earlier than other American countries. For example, in the 17th century, Prince John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen brought scientists and artists to study Brazil's nature.

For a long time, Portugal did not allow foreigners into its overseas lands. This changed when the royal family moved to Brazil and opened its ports in 1808. This opening, combined with the Napoleonic Wars making travel difficult in Europe, created a huge interest in Brazil among European scientists.

Maria Leopoldina had a special interest in natural sciences, especially geology and botany, from a young age. Her father, Emperor Francis I, supported her studies.

So, when her wedding to Dom Pedro was announced in 1817, the Austrian court organized a major scientific expedition to Brazil. This mission included scientists from Austria and Bavaria. Among them were Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, a doctor and botanist, and Johann Baptist von Spix, a zoologist. Other notable scientists included Johann Christian Mikan, a botanist and entomologist, and Thomas Ender, a painter. Their goal was to collect plant and animal specimens and create illustrations of people and landscapes for a museum in Vienna.

They were fascinated by the idea of exploring the New World and its plants, animals, and native people. This interest was partly due to the famous book by German geographer Alexander von Humboldt, which described his travels in South America.

Maria Leopoldina's interest in science led her to influence her father-in-law to create the Royal Museum (now the National Museum of Brazil) in 1818. This museum helped scientists explore Brazil. In 1824, the British writer Maria Graham visited and became a friend of Maria Leopoldina. They shared an interest in science, and Maria Graham even helped educate Maria Leopoldina's eldest daughter, Maria da Glória.

Regent and Empress of Brazil

The Path to Independence

The year 1821 was very important for Maria Leopoldina. She came from a very traditional European family, used to absolute monarchies. In June 1821, she wrote to her father that her husband, Dom Pedro, "loves the new ideas," referring to new constitutional and liberal political values. She had seen how Napoleon Bonaparte changed European politics, which influenced her views.

As tensions grew between Portugal and Brazil, Maria Leopoldina became more involved in the political events leading to Brazil's independence. She worked closely with José Bonifácio de Andrada, a key figure in the independence movement. During this time, she shifted from her conservative upbringing and began to support a more liberal, constitutional government for Brazil.

Because of a revolution in Portugal in 1820, the Portuguese court was forced to return to Portugal on April 25, 1821. King John VI left Dom Pedro in Brazil as regent, with wide powers. At first, Dom Pedro struggled to control the chaos. The conflict between Portuguese and Brazilians became clear. Maria Leopoldina's letters show that she strongly supported the Brazilian people and wanted the country to be independent. This is why Brazilians loved her.

Supporting Brazil's Independence

Maria Leopoldina had grown up fearing popular revolutions, remembering her great-aunt Marie Antoinette, who was guillotined during the French Revolution. However, in Brazil, the movement for independence was different. Brazilians saw Dom Pedro and Maria Leopoldina as allies, not as rulers to be overthrown.

Maria Leopoldina, despite her traditional education, became a strong supporter of Brazil's independence, even before Dom Pedro. She wrote to her friends in Europe, clearly showing her support for Brazil and her thoughts on Portuguese rule. She believed that staying in Brazil was important to protect the royal family's power against liberal changes. Dom Pedro, however, lacked political experience and often asked his father to let him return to Portugal.

Maria Leopoldina's decision to stay was strengthened by José Bonifácio de Andrada. With his help, she convinced her husband that Brazil's unity could only be maintained if they both stayed. Finally, on January 9, 1822, Dom Pedro famously declared: "Fico!" (I am staying!). At 24, Maria Leopoldina made a choice that meant she would live far from her family in Europe for the rest of her life.

Two days later, Dom Pedro's decision caused anger among the Portuguese Cortes (parliament). A revolution broke out, and government buildings were burned. Dom Pedro went to confront the Cortes with his troops. Maria Leopoldina went on stage at the theater and announced: "Remain calm, my husband has everything under control!" This announcement was met with cheers and showed her support for the Brazilian people.

However, Maria Leopoldina knew her life was in danger. She was seven months pregnant and quickly fled to Santa Cruz with her two young children, Maria da Glória (3 years old) and João-Carlos (11 months old). The journey was difficult, and sadly, João Carlos died on February 4, 1822.

Maria Leopoldina's letters from late 1821 show that she was more committed to Brazil than Dom Pedro. She believed they had to stay in Brazil and defy the Portuguese court. Her "Dia do Fico" (Day of I Am Staying) was earlier than her husband's.

On August 6, 1822, Dom Pedro signed a document for friendly nations, criticizing Lisbon's control over Brazil. He asked other nations to deal directly with Rio de Janeiro. Even then, he didn't want to completely break ties with Portugal. Maria Leopoldina, however, realized that Portugal was already lost and that Brazil could become a powerful nation. She knew that if Dom Pedro left, Brazil might split into many small republics, like the Spanish colonies.

Maria Leopoldina's strong support for Brazil is clear in a letter she wrote to Dom Pedro before independence:

"You need to come back as soon as possible. Be persuaded that it is not only love that makes me want your immediate presence more than ever, but the circumstances in which the beloved Brazil is. Only your presence, a lot of energy and rigor can save you from ruin".

Thousands of people in Rio de Janeiro signed petitions asking the regents to stay in Brazil. After the Dia do Fico, a new government was formed under José Bonifácio, and Dom Pedro gained the people's trust. On February 15, 1822, Portuguese troops left Rio de Janeiro, symbolizing the break with Portugal.

Becoming Empress of Brazil

In August 1822, when her husband traveled to São Paulo, Maria Leopoldina was named his official representative and Regent. A document on August 13, 1822, gave her full power to make political decisions while he was away. She had a huge influence on Brazil's independence. Brazilians knew Portugal wanted Dom Pedro to return and make Brazil a simple colony again. There were fears of civil war.

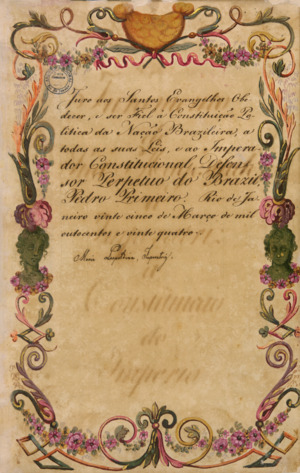

A new set of demands from Lisbon arrived in Rio de Janeiro. Without time to wait for Dom Pedro, Maria Leopoldina, advised by José Bonifácio, met with the Council of State on September 2, 1822. She signed the Decree of Independence, declaring Brazil separate from Portugal. She sent a letter to Dom Pedro, urging him: "The fruit is ripe, pick it up, otherwise it will rot."

Dom Pedro declared the Independence of Brazil on September 7, 1822, after receiving his wife's letter in São Paulo. Maria Leopoldina had also sent him news from Lisbon that criticized his actions.

While waiting for her husband to return, Maria Leopoldina, as the interim ruler of an independent country, helped design the flag of Brazil. She combined the green of the House of Braganza (Dom Pedro's family) and the golden yellow of the House of Habsburg (her family). Other sources say Jean-Baptiste Debret designed the flag, with the green rectangle representing forests and the yellow rhombus representing gold. After independence, Maria Leopoldina worked hard to get European countries to recognize Brazil as a new nation, writing letters to her father, the Emperor of Austria, and her father-in-law, the King of Portugal.

Maria Leopoldina became Brazil's first Empress consort. She was officially recognized on December 1, 1822, during her husband's coronation as Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor of Brazil. As Brazil was the only monarchy in South America at the time, Maria Leopoldina was the first Empress of the New World.

Bahia's Role in Independence

Bahia was an important region in Brazil's independence. After September 7, 1822, there was fighting between those loyal to Portugal and those who wanted independence. Imperial troops won on July 2, 1823.

Bahian women played an active role. Maria Quitéria joined the army secretly and was honored by Emperor Pedro I. Maria Felipa de Oliveira, an Afro-Brazilian woman, led other women in defending Itaparica Island. Sister Joana Angélica, an abbess, gave her life to prevent Portuguese troops from entering her convent.

The political awareness of women is also shown in a letter from 186 Bahian ladies to Maria Leopoldina in August 1822. They thanked her for her part in the patriotic decisions. Maria Leopoldina wrote to her husband that this showed women were "more cheerful and are more adherent to the good cause." In 1826, the Emperor and Empress visited Salvador, Bahia, to recognize its support.

Later Life and Passing

Public Concern for the Empress

King John VI of Portugal passed away on March 10, 1826. Dom Pedro then became King Pedro IV of Portugal, while remaining Emperor Pedro I of Brazil. Maria Leopoldina became both Empress of Brazil and Queen of Portugal. However, Dom Pedro knew that Brazil and Portugal could not be united under one ruler. So, less than two months later, on May 2, he gave up the Portuguese crown to their eldest daughter, Maria da Glória, who became Queen Dona Maria II.

Dom Pedro's relationship with Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo, Marchioness of Santos, caused Maria Leopoldina great sadness and distress. She became very depressed. Her health quickly worsened in November 1826, with cramps, vomiting, and confusion. She was also pregnant again.

Maria Leopoldina was loved by the Brazilian people, even more than Dom Pedro. Rio de Janeiro watched her health closely. The Prussian ambassador, Theremim, reported how much the public loved the Empress:

"The sadness among the people was indescribable; never [...] has such a strong feeling been seen. The people were literally on their knees praying to God for the Empress. Churches were full, and everyone prayed at home. Men formed processions, not for show, but with true devotion. Such unexpected love, shown openly, must have been a real comfort for the sick Empress."

On December 7, 1826, a newspaper reported that people in Rio de Janeiro were constantly asking about the Empress's "afflictive state." They gathered at the Imperial Quinta (palace), crying and worried, all asking, "How is the Empress?"

Many processions with religious images went to the Imperial Chapel, praying for her recovery. People were deeply devoted to her.

Disagreements on Cause of Death

There are different ideas about what caused Maria Leopoldina's death. Some say she died from complications after childbirth, while Dom Pedro was away inspecting troops.

Another theory, supported by some historians, suggests she died from injuries during an argument with her husband, possibly in the presence of his mistress. The Empress was already in a deep depression and 12 weeks pregnant, and her health was very poor.

However, recent studies suggest this theory might not be accurate. A letter supposedly written by Maria Leopoldina describing an attack has been questioned as possibly fake. The original letter has never been found.

Forensic analysis conducted in 2012 found no bone fractures, which would rule out a fall or physical attack as the direct cause of death. The coroner, Luiz Roberto Fontes, stated that Maria Leopoldina had a serious infection that led to a miscarriage and her death. She had bleeding, fever, and diarrhea, indicating a severe infection. She miscarried a male fetus on December 2, days before her death. Her health did not improve, and she continued to have fever and bleeding, leading to a septic condition.

Reactions and Legacy

During Maria Leopoldina's illness, rumors spread that she was being held prisoner or poisoned. The popularity of Domitila de Castro, Dom Pedro's mistress, dropped even further. Her house was attacked, and her brother-in-law was shot. Palace officials suggested she should no longer be at court.

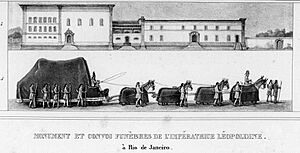

Maria Leopoldina passed away on December 11, 1826, at the São Cristóvão Palace in Rio de Janeiro, five weeks before her 30th birthday. Her death was deeply mourned by the nation, as she was much loved by the people.

Her death greatly damaged Dom Pedro I's reputation, making his second marriage difficult.

Her body was placed in three coffins: one of pine, one of lead, and one of cedar.

She was buried on December 14, 1826, in the church of the Ajuda Convent. Later, her remains were moved to the Santo Antônio Convent in 1911. In 1954, her remains were finally moved to a green granite sarcophagus in the Imperial Crypt under the Ipiranga Monument in São Paulo.

Legacy and Importance

Maria Leopoldina is often seen as a sad figure due to her husband's affairs. However, recent historical studies show her as a strong and active figure in Brazil's history.

She played a huge role in Brazilian politics, especially during the period leading up to independence in 1822. While Dom Pedro I still considered keeping Brazil united with Portugal, Maria Leopoldina had already decided that complete independence was the best path. Her education and strong sense of duty were vital for Brazil, especially after King John VI returned to Lisbon. Even though she came from an aristocratic, absolute monarchy, Maria Leopoldina supported more representative forms of government for Brazil, influenced by liberal ideas.

Brazilians greatly respected and admired Maria Leopoldina from the moment she arrived. She was very popular, especially among the poor and enslaved people. After her death, she was called the "Mother of Brazilians." People even asked for her to be given the title "Guardian Angel of this nascent Empire." During her final illness, people held processions in the streets of Rio de Janeiro, and churches were filled with sad people. News of her death caused widespread grief. There are reports of enslaved people crying out, "Our mother died. What will become of us? Who will take sides with blacks?" Her death significantly reduced Dom Pedro I's popularity. Historian Carlos H. Oberacker Júnior says that "rarely has a foreigner been so dear and recognized by a people like her."

Maria Leopoldina also tried to end slavery. She encouraged European immigration to Brazil to change the type of labor. Her arrival led to the beginning of German immigration, first with Swiss settlers in Nova Friburgo, and later Germans settling in southern Brazil.

Her importance is also linked to the scientific mission that came with her from Italy. Because of her interest in botany and geology, two German scientists, botanist Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius and zoologist Johann Baptist von Spix, came with her, along with painter Thomas Ender. Their research resulted in important works like Viagem pelo Brasil and Flora Brasiliensis, which classified and illustrated thousands of native plant species. These scientists traveled over 10,000 kilometers across Brazil.

Maria Leopoldina's decision to stay in Brazil still sparks debate. Some see it as a revolutionary act, while others see her as a clever strategist. Maria Celi Chaves Vasconcelos, a professor specializing in the education of noble women, believes there is no sign of rebellion in Maria Leopoldina's writings. She thinks Maria Leopoldina was simply knowledgeable enough about political history to make the right decision for independence. However, historian Paulo Rezzutti argues that Maria Leopoldina was a revolutionary woman because she was the first to make high-level political decisions in Brazil.

Depictions in Culture

Empress Maria Leopoldina has been shown in movies and TV shows:

- Kate Hansen played her in the film Independência ou Morte (1972).

- Maria Padilha played her in the miniseries Marquesa de Santos (1984).

- Érika Evantini played her in the miniseries O Quinto dos Infernos (2002).

- Letícia Colin played her in the telenovela Novo Mundo (2017).

Her life was also the theme for the 1996 parade of the samba school Imperatriz Leopoldinense, which is indirectly named after her. In 2007, actress Ester Elias played Maria Leopoldina in the musical Império. In 2018, she was honored by the Tom Maior samba school at the São Paulo carnival.

Honours

| Styles of Empress Leopoldina of Brazil |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | Her Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves:

United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves:

- Dame Grand Mistress of the Order of Saint Isabel

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa

Empire of Brazil:

Empire of Brazil:

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross

Austrian Empire: Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross

Austrian Empire: Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa

Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa Kingdom of Bavaria: Dame of the Order of Saint Elizabeth

Kingdom of Bavaria: Dame of the Order of Saint Elizabeth

Children

Maria Leopoldina had nine pregnancies. Her first child, Maria da Glória, was born on April 4, 1819. She had two miscarriages in 1819 and 1820. Her first living son, João Carlos, Prince of Beira, was born on March 6, 1821, but sadly passed away on February 4, 1822, at 11 months old. Her next three children were daughters: Januária (born 1822), Paula (born 1823), and Francisca (born 1824). Her long-awaited son and heir, the future Emperor Dom Pedro II, was born on December 2, 1825. Her ninth and last pregnancy was fatal, as she died from complications after a miscarriage.

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maria II of Portugal |  |

4 April 1819 – 15 November 1853 |

Queen of Portugal from 1826 to 1853. She married Auguste de Beauharnais, 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg and later Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who became King Dom Fernando II. She had eleven children. |

| Miguel, Prince of Beira | 26 April 1820 | Passed away shortly after birth. | |

| João Carlos, Prince of Beira | 6 March 1821 – 4 February 1822 |

Passed away at 11 months old. | |

| Princess Januária of Brazil |  |

11 March 1822 – 13 March 1901 |

Married Prince Luigi, Count of Aquila. She had four children. |

| Princess Paula of Brazil |  |

17 February 1823 – 16 January 1833 |

Passed away at age 9, likely from meningitis. |

| Princess Francisca of Brazil |  |

2 August 1824 – 27 March 1898 |

Married Prince François, Prince of Joinville. She had three children. |

| Pedro II of Brazil |  |

2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891 |

Emperor of Brazil from 1831 to 1889. He married Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies and had four children. |

See also

In Spanish: María Leopoldina de Austria para niños

In Spanish: María Leopoldina de Austria para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |