Colonial Brazil facts for kids

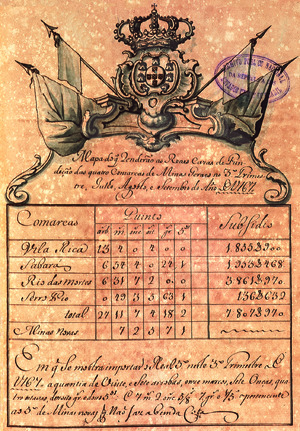

Quick facts for kids

Colonial Brazil

Brasil Colonial

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1500/1534–1808 | |||||||||

Brazil in 1534

|

|||||||||

Brazil in 1750

|

|||||||||

| Status | Colony of the Kingdom of Portugal | ||||||||

| Capital | Salvador (1549–1763) Rio de Janeiro (1763–1822) |

||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese (official) Tupí Austral, Nheengatu, many indigenous languages |

||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic (official) Afro-Brazilian religions, Judaism, indigenous practices |

||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

|

• 1500–1521

|

Manuel I (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1777–1815

|

Maria I (last) | ||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||

|

• 1549–1553

|

Tomé de Sousa (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1806–1808

|

Marcos de Noronha, 8th Count of the Arcos (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral on behalf of the Portuguese Empire

|

22 April 1500/1534 | ||||||||

|

• Elevation to Kingdom and creation of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves

|

13 December 1808 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

|

• Total

|

8,100,200 km2 (3,127,500 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | BR | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Colonial Brazil was a time in history when Brazil was a colony of Portugal. This period started in 1500, when the Portuguese first arrived. It ended in 1815, when Brazil became a kingdom, joining with Portugal.

For about 300 years, Brazil's economy focused on exporting valuable products. First, they extracted brazilwood in the 1500s. This wood was used for a red dye and gave Brazil its name. Later, sugar production became very important from the 1500s to the 1700s. Finally, in the 1700s, people found gold and diamonds. Most of the hard work for these industries was done by enslaved people, especially those brought from Africa.

Unlike the nearby Spanish colonies, which had many different areas ruled by viceroys, Brazil was mostly settled along the coast. Portuguese people and a large number of enslaved Africans lived there. They worked on sugar farms and in mines. Brazil's economy went through cycles of boom and bust, depending on what products were popular. The sugar industry faced problems when other European countries started growing sugar in the Caribbean. Gold and diamonds were found in southern Brazil later on. Many Brazilian cities were ports, and the capital city moved several times as different export products became more or less important.

Brazil remained one large country under a king after it became independent. This was different from Spanish America, which split into many smaller countries. The Portuguese language and the Roman Catholic faith helped unite Brazilian society. Since Brazil was the only country in the Americas that spoke Portuguese, the language became a very important part of its identity.

Contents

- First European Contact and Early Years (1494–1530)

- How Brazil was Colonized

- The Sugar Age (1530–1700): Brazil's Sweet Success

- Exploring Inland: The Entradas and Bandeiras

- Early Gold Discoveries (1600s)

- The Gold Cycle (1700s): A Golden Age

- Colonial Changes to Brazil's Environment

- The Royal Court in Brazil (1808–1821)

- Territorial Evolution of Colonial Brazil

- Administrative Changes Over Time

- See also

First European Contact and Early Years (1494–1530)

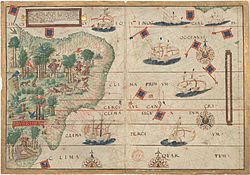

Portugal was a leader in exploring new sea routes. These routes connected different parts of the world for the first time, starting a process called globalization. During these years, Portuguese explorers made big improvements in cartography (map-making), shipbuilding, and navigational instruments.

In 1494, Portugal and Spain signed the Treaty of Tordesillas. This agreement divided the "New World" between them. In 1500, a Portuguese explorer named Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in what is now Brazil. He claimed the land for the King of Portugal. The Portuguese soon realized that brazilwood was valuable for its red dye. They tried to make the native people cut down these trees.

The Age of Exploration: Portugal's Journey

Portuguese sailors began exploring in the early 1400s. They started by taking a Muslim fort in North Africa. Then, they sailed down the coast of West Africa and across the Indian Ocean to Asia. They were looking for gold, ivory, and enslaved Africans. The Portuguese set up trading posts called feitorias. These were small, permanent settlements that helped with trade. Private investors paid for these posts, which saved the Portuguese king money.

On islands like the Azores and Madeira, the Portuguese started growing sugarcane. They used forced labor for this. This was a practice they would later use in Brazil.

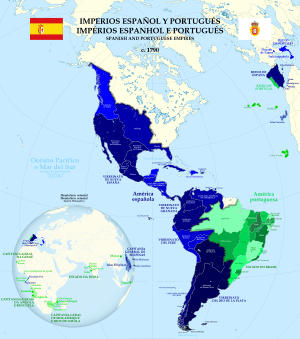

The Portuguese "discovery" of Brazil happened after several agreements between Portugal and Spain. The most important was the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty drew an imaginary line around the world. All land found east of this line belonged to Portugal. Everything to the west went to Spain. This treaty meant that a large part of South America would be settled by Portugal. It was a very important document in Brazil's history.

Arrival and First Steps in Brazil

On April 22, 1500, a fleet led by Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in Brazil. He claimed the land for King Manuel I of Portugal. Even though some people debate if other Portuguese explorers were there before, this date is widely accepted as the "discovery" of Brazil by Europeans. The place where Cabral landed is now called Porto Seguro, meaning "safe harbor." Cabral was on his way to India with 13 ships and over 1,000 men. He spent ten days in Brazil.

The Portuguese had learned a lot from exploring other new lands. They knew it was important to avoid fighting with local people. Cabral tried to communicate using music and humor. Just before Cabral arrived, another explorer, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, had a bad experience. His men fought with the native people, and eight of them were killed. Cabral learned from this. He left two men, called degredados (criminal exiles), in Brazil. Their job was to learn the native languages and become interpreters for future visits.

After Cabral's trip, Portugal focused on its rich lands in Africa and India. They didn't show much interest in Brazil at first. From 1500 to 1530, only a few Portuguese ships came to Brazil. They mostly mapped the coast and collected brazilwood. This wood was used in Europe to make valuable red dye for fancy clothes. To get the brazilwood, Europeans relied on the native people. The natives initially worked in exchange for European goods like mirrors, scissors, knives, and axes.

During these early years, the Portuguese often got help from Europeans who lived with the native people. These Europeans knew the local languages and cultures. One famous example was João Ramalho, who lived with the Guaianaz tribe. Another was Diogo Álvares Correia, known as Caramuru, who lived with the Tupinambá near today's Salvador.

Over time, the Portuguese realized that other European countries, especially France, were also taking brazilwood. The Portuguese king worried about foreigners taking his land. He also hoped to find valuable minerals. So, in 1530, Portugal sent a large expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa. Their job was to patrol the coast, stop the French, and create the first colonial villages, like São Vicente.

How Brazil was Colonized

Brazil didn't have big, complex civilizations like the Aztec or Inca empires in Mexico and Peru. This meant the Portuguese couldn't just take over an existing system. Also, they didn't find much gold or silver until the 1700s. Because of this, Portugal's relationship with Brazil was different from Spain's with its colonies. At first, Brazil was seen more as a trading post to help trade with India, not a place to build a new society.

As time went on, the Portuguese king realized that just having trading posts wasn't enough to control the land. He decided the best way to keep Brazil was to settle it. So, the land was divided into fifteen private areas called captaincies. These were passed down through families. Only two of them, Pernambuco and São Vicente, did well. Pernambuco succeeded by growing sugarcane. São Vicente made money by trading in enslaved native people. The other thirteen captaincies failed.

Because of these failures, the king decided that colonizing Brazil should be a royal effort, not a private one. In 1549, Tomé de Sousa sailed to Brazil to set up a central government. He brought Jesuit priests with him. The Jesuits started missions, helped many native people avoid slavery, learned native languages, and converted many to Catholicism. Their work helped the Portuguese remove the French from a colony they had started near today's Rio de Janeiro.

The Captaincies: Early Attempts at Control

The first plan to colonize Brazil used a system called "hereditary captaincies" (Capitanias Hereditárias). This system had worked well before in colonizing Madeira Island. The king gave these captaincies to private individuals, like merchants, soldiers, and nobles. This saved the Portuguese government a lot of money. The captains had a lot of power to manage and profit from their land.

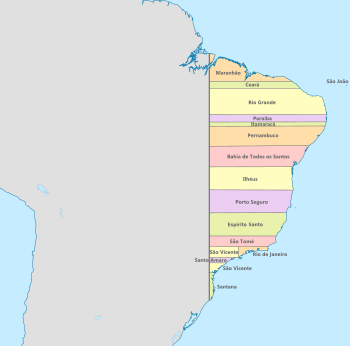

Between 1534 and 1536, King John III of Portugal divided Brazil into 15 captaincies. He gave them to people who wanted to explore and develop them. This division also showed how important large areas of land were for growing brazilwood and sugar.

Out of the 15 original captaincies, only two, Pernambuco and São Vicente, were successful. Most failed because of resistance from native people, shipwrecks, and fights among the colonists. The king also didn't have strong control over these areas. Pernambuco, the most successful, belonged to Duarte Coelho. He founded the city of Olinda in 1536. His captaincy grew rich from sugarcane mills built after 1542. Sugar became Brazil's main export for the next 150 years. São Vicente also produced sugar, but its main business was trading enslaved native people.

Governors General: Centralizing Power

Since most captaincies failed and French ships were a threat, King John III decided to take royal control of Brazil's colonization. In 1549, a large fleet led by Tomé de Sousa sailed to Brazil. His job was to create a central government for the colony. Tomé de Sousa was the first Governor General of Brazil. He had detailed instructions from the king on how to manage and develop the colony.

His first action was to found the capital city, Salvador da Bahia, in northeastern Brazil. The city was built on a hill by a bay. It had an upper area for government and a lower area for trade and the harbor. Tomé de Sousa also visited the other captaincies to help them rebuild and improve their economies. In 1551, the first Catholic church area, the Diocese of São Salvador da Bahia, was set up in Salvador.

The second Governor General, Duarte da Costa (1553–1557), faced many challenges. He had conflicts with native people and arguments with other colonists and the bishop. Wars against the native people around Salvador took up much of his time. In 1556, the first bishop of Brazil was killed and eaten by the Caeté natives after a shipwreck. This shows how tense things were between the Portuguese and many native tribes.

The third Governor General was Mem de Sá (1557–1573). He was a good leader. He managed to defeat the native people and, with the help of the Jesuits, he drove the French out of their colony called France Antarctique. His nephew, Estácio de Sá, founded the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1565 as part of this effort.

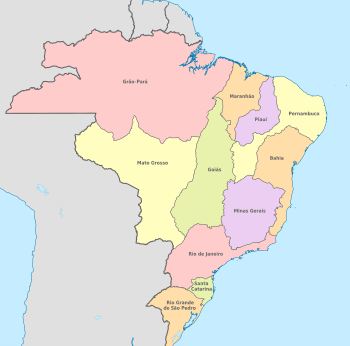

Brazil was so big that it was divided into two parts after 1621. King Philip III of Spain created the states of Brasil, with Salvador as its capital, and Maranhão, with its capital in São Luís. Later, Maranhão was divided even more. Each state had its own Governor.

After 1640, governors from noble families started using the title Vice-rei (Viceroy). In 1763, the capital of the Estado do Brazil moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. In 1775, all the Brazilian states were united into the Viceroyalty of Brazil. Rio de Janeiro became the capital, and the king's representative was officially called the Viceroy of Brazil.

Like in Portugal, every colonial village and city had a city council (câmara municipal). Important people in society, like landowners and merchants, were members. These councils managed trade, public buildings, and prisons.

Jesuit Missions: Faith and Influence

Tomé de Sousa, Brazil's first Governor General, brought the first group of Jesuits to the colony. The Jesuits were very important in Brazil's colonial history. Spreading the Catholic faith was a key reason for Portugal's conquests. The King fully supported the Jesuits, telling Tomé de Sousa to help them convert the native people.

The first Jesuits, led by Father Manuel da Nóbrega and including José de Anchieta, set up missions in Salvador and São Paulo. Nóbrega and Anchieta helped defeat the French colonists by making peace with the Tamoio native people. The Jesuits also helped found the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1565.

The Jesuits were good at converting native people to Catholicism because they understood native culture and languages. José de Anchieta wrote the first grammar of the Tupi language. The Jesuits often gathered native people into communities called aldeias. In these communities, natives worked together and learned about Christianity.

The Jesuits often argued with other colonists who wanted to enslave the native people. They also had disagreements with the Catholic Church leaders. The Jesuits saved many native people from slavery. However, their actions also changed the natives' traditional way of life. They also accidentally helped spread diseases that the native people had no protection against. Enslaved labor was vital for Brazil's economy. The Jesuits usually did not object to the enslavement of African people.

French Incursions: Challenges to Portuguese Control

The potential wealth of Brazil attracted the French. They didn't recognize the Treaty of Tordesillas. In 1555, Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon started a French settlement in Guanabara Bay, near today's Rio de Janeiro. This colony, called France Antarctique, led to conflict with Governor General Mem de Sá. He fought against the colony in 1560. His nephew, Estácio de Sá, founded Rio de Janeiro in 1565 and drove out the last French settlers in 1567. The Jesuit priests Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta helped the Portuguese win by calming the native people who supported the French.

Another French colony, France Équinoxiale, was founded in 1612 in São Luís, in northern Brazil. But in 1614, the Portuguese again expelled the French from São Luís.

The Sugar Age (1530–1700): Brazil's Sweet Success

When early attempts to find gold and silver failed, the Portuguese colonists turned to farming. They grew crops to export to Europe. While tobacco and cotton were produced, sugar became the most important product until the early 1700s. The first sugarcane farms were set up in the mid-1500s. They were key to the success of the captaincies of São Vicente and Pernambuco. Sugarcane plantations quickly spread along Brazil's coast.

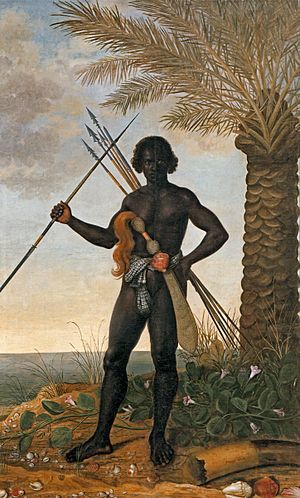

At first, the Portuguese tried to use enslaved native people for sugar farming. But they soon started bringing in enslaved black Africans. This shift happened even though the enslavement of native people continued. By 1580, as many as 40,000 native people might have been taken from inland areas to work as slaves.

The time when sugar was the main economic activity (1530 – around 1700) is called the Sugar Age in Brazil. Sugar farms were complex. They included a casa-grande (big house) where the owner lived, and the senzala, where enslaved people were kept.

The Portuguese had trading posts in West Africa where they bought enslaved people from African slave traders. These enslaved Africans were then sent to Brazil on crowded slave ships. Enslaved Africans were preferred because many came from farming societies. They were also less likely to get sick from Old World diseases than native people. The demand for enslaved Africans grew with the sugar and gold industries. From 1600 to 1650, sugar made up 95% of Brazil's exports.

Working conditions for enslaved people were very harsh, especially in the Bahia region where sugar was the main crop. It was often cheaper for slave owners to work enslaved people to death and then buy new ones. In other areas, where crops like manioc were grown, conditions were sometimes better.

Portugal tried to control all trade. Brazil could only export and import goods from Portugal and other Portuguese colonies. Brazil exported sugar, tobacco, cotton, and native products. It imported wine, olive oil, textiles, and luxury goods from Portugal. Africa was crucial for supplying enslaved people. Brazilian slave traders often traded cachaça (a drink made from sugarcane) and shells for slaves. This created a "triangular trade" route between Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Merchants were very important during the Sugar Age. They connected the sugar farms, Portuguese ports, and Europe. Even though Brazilian sugar was high quality, the industry faced problems in the 1600s and 1700s. The Dutch and French started producing sugar in the Caribbean, which was closer to Europe. This caused sugar prices to drop.

Cities and Towns: Centers of Life

Brazil had cities and towns along its coast. These were important for the church, government, and merchants. Unlike many parts of Spanish America, there wasn't a large native population that had already built cities. Port cities like Olinda (founded 1537), Salvador da Bahia (1549), and Rio de Janeiro (1565) were vital for trade and defense against pirates. Only São Paulo, in the Minas Gerais region, was an important city away from the coast. Brazilian cities often didn't have the neat, grid-like layout of Spanish colonial towns, partly because of the hilly land.

In 1580, a problem with who would be the next king led to Portugal and Spain being ruled by the same king, Philip II of Spain. This was called the Iberian Union. It lasted until 1640, when the Portuguese revolted. During this time, both kingdoms kept their own separate governments. For Portuguese merchants, especially those who were New Christians (Jews who converted to Christianity), this union opened up new trade chances, especially in the slave trade to Spanish America.

The Netherlands became independent from Spain in 1581. Philip II then banned trade with Dutch ships, including in Brazil. Since the Dutch had invested a lot of money in Brazil's sugar production and were important for shipping sugar, conflicts began. Dutch privateers (pirates working for their government) attacked the coast. They looted Salvador in 1604, taking gold and silver.

Dutch Rule in Northeastern Brazil (1630–1654)

From 1630 to 1654, the Dutch took control of parts of northeastern Brazil. They settled in commercial Recife and aristocratic Olinda. By 1635, the Dutch controlled a long part of the coast. The Dutch governor, Count John Maurice of Nassau (1637–1644), invited scientists to study the local plants and animals. He also planned a city design for Recife and Olinda. After many years of fighting, the Dutch finally left in 1654. The Portuguese paid them a war debt. Few Dutch cultural influences remain today.

Slavery in Brazil: A Harsh Reality

Unlike Spanish America, Brazil was a society built on slavery from the very beginning. The trade of enslaved Africans was a core part of the colony's economy and society. More enslaved people were brought to Brazil than to the Thirteen Colonies (which became the USA). It's estimated that about 35% of all Africans captured in the Atlantic slave trade were sent to Brazil. The slave trade in Brazil continued for almost 200 years, longer than in any other country in the Americas.

Enslaved Africans were considered more valuable than enslaved native people. Many Africans came from farming societies, so they already knew how to work the sugar plantations. They were also more resistant to Old World diseases that killed many native people. And they were less likely to run away, as their homes were so far away. However, many enslaved Africans did escape. They created their own communities called quilombos. These often became strong political and economic groups.

Runaway Slave Settlements: The Quilombos

Work on sugar plantations in Northeast Brazil relied heavily on enslaved labor, mostly from central Africa. These enslaved people resisted slavery in many ways. Some would work slowly or damage tools. Others would harm themselves or their babies, or seek revenge on their masters. Many also ran away. Brazil's thick forests made it easier for them to escape.

From the early 1600s, runaway slaves started organizing settlements in the Brazilian countryside. These settlements, called mocambos and quilombos, were usually small and close to sugar fields. They attracted not only African slaves but also native people.

Portuguese colonists often saw quilombos as "parasitic." They believed the quilombos survived by stealing livestock and crops. Sometimes, the victims of these raids were not white sugar planters, but black people who grew their own food. However, other records show that people in quilombos also found gold and diamonds. They even traded with white-controlled cities.

The largest of the quilombos was the Quilombo dos Palmares, located in today's Alagoas state. It grew to include thousands of people during a time when Portuguese rule was weak due to the Dutch invasion. Palmares was led by Ganga Zumba and later by Zumbi. The names for these settlements and leaders came from Angola. The Dutch and later the Portuguese tried many times to conquer Palmares. Finally, an army led by Domingos Jorge Velho destroyed the great quilombo and killed Zumbi in 1695. Some quilombos have survived to this day as isolated rural communities.

Portuguese colonists wanted to destroy these runaway communities. They feared that enslaved people would revolt. They tried to stop escapes and close off escape routes. Slave catchers led expeditions to destroy fugitive communities. They would kill or re-enslave the inhabitants. These expeditions were carried out by soldiers and mercenaries. As a result, many quilombos were heavily fortified. Native people were sometimes used as slave catchers or as part of defenses against slave uprisings. However, some native people also helped those who escaped slavery by letting them join their villages.

Many details about the inner workings of quilombos are still a mystery. The information we have often comes from colonial records of their destruction. We know more about the Quilombo dos Palmares because it was the largest and longest-lasting runaway community. Quilombos were influenced by both African and European cultures. They often copied parts of colonial society. For example, slavery, which also existed in Africa, continued in Palmares. Quilombos were likely made up of people from different African groups. They also blended African and Christian religious beliefs.

In Minas Gerais, the mining economy actually helped quilombos form. Skilled enslaved people who worked in mines were very valuable. As long as they kept giving their findings to their owners, they were often allowed to move freely in the mining areas. Enslaved and freed black people made up most of the population there. Runaways could easily hide among them. The mountains and unsettled land also provided good hiding spots.

Exploring Inland: The Entradas and Bandeiras

Since the 1500s, people tried to explore Brazil's inland areas. They mostly hoped to find valuable minerals, like the silver mines found by the Spanish in Potosí (now in Bolivia). Since no riches were found at first, colonization stayed mostly on the coast. The climate and soil there were good for sugarcane plantations.

Brazil's economy was set up to export goods, not primarily for Europeans to settle permanently. This led to a culture of taking resources without thinking about the long-term effects on the land or labor. On sugar plantations, the land was used up quickly. When the soil became poor, owners would just abandon their fields and move to new ones. They thought the supply of land was endless.

Expeditions into Brazil's interior were of two types: the entradas and the bandeiras. The entradas were official trips by the Portuguese government. They were paid for by the colonial government. Their main goal was to find minerals and map unknown areas. The bandeiras, on the other hand, were private trips. They were mostly organized and carried out by settlers from the São Paulo region, called Paulistas. These adventurers, known as bandeirantes, aimed to capture native people for slavery and find mineral wealth.

Bandeira expeditions often included a leader, his enslaved people, a priest, a writer, a mapmaker, white colonists, animals, and doctors. These groups would march for several months into lands not yet settled by colonists, which were the homelands of native people. The Paulistas, who were often of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, knew the old native pathways through the Brazilian interior. They were also used to the difficult conditions of these journeys.

At the end of the 1600s, the bandeirantes found gold in central Brazil, in the region of Minas Gerais. This started a gold rush that led to many new towns and cities in the interior during the 1700s. These inland expeditions also pushed the borders of colonial Brazil further west, beyond the limits set by the Treaty of Tordesillas.

Mixing Cultures and People on the Frontier

When white people, like those avoiding taxes or military service, went into the wild areas of the Atlantic Forest, they formed mixed-race settlements. These places became centers of "cultural and genetic exchange."

Some native tribes, like the Caiapo, managed to fight off the Europeans for years. They even started using some European farming methods. However, as mining expanded, many native tribes were pushed off their land. More and more of them went to the aldeias (Jesuit communities) to avoid being enslaved or fighting with other native groups. In 1755, the Marquis of Pombal made it illegal to enslave natives. He also made it legal for Europeans to marry natives. This was an attempt to make the native population more like European peasants.

On the frontier, people of native, European, and African backgrounds mixed. This led to new cultural exchanges. Portuguese officials usually refused to work with quilombos, seeing them as a threat. But these mixed settlements, called "caboclo frontiers," helped integrate native people into new customs. Runaway slaves who formed quilombos or hid in the forest met native people and taught them Portuguese. One official noted that a runaway black person could do more among the native people than all the missionaries combined. However, colonial officials did not approve of relationships between runaway black slaves and native people.

People on the "caboclo frontier" shared beliefs, music, remedies, and hunting techniques. The Tupi language added new words to Portuguese for plants, animals, and places. African words, like fubà (cornmeal), also became part of Brazilian Portuguese.

Black Brotherhoods in Bahia

The Black Irmandade (Brotherhood) in Bahia shows how black and mixed-race people started creating their own culture. Even though black people were often seen as "the lowest," their farming skills and their arrival with white Europeans gave them a slightly higher social standing. These Afro-Portuguese people developed a rich culture, especially seen in their celebrations in Bahia. These events mixed African beliefs with Christian ideas and the experience of living in a new land. The Irmandade valued elaborate burials. Dying alone was seen as a sign of poverty. The Irmandade of Bahia highlights the growing mix of races and cultures among native people, African slaves, and white Europeans in Brazil.

Early Gold Discoveries (1600s)

While the biggest gold deposits were found at the end of the 1600s, gold was first found in the São Vicente area in the late 1500s. For about a century, not much gold was found, but two important ways of dealing with gold began. First, the Portuguese king forced native people into enslaved labor in the first goldfields. Later, hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were brought to work in the mines. Second, people called faiscadores or garimpeiros illegally searched for and mined gold. They avoided Portuguese taxes on precious metals. This problem of illegal mining continued for over a hundred years.

The Gold Cycle (1700s): A Golden Age

The discovery of gold brought great excitement to Portugal. Its economy was struggling after years of wars. A gold rush quickly began. People from other parts of Brazil and from Portugal flooded into the region in the early 1700s. The large area in central Brazil where gold was found became known as Minas Gerais (General Mines). Gold mining became the main economic activity in colonial Brazil during the 1700s.

In Portugal, the gold was mostly used to buy manufactured goods like textiles and weapons from other European countries. Portugal didn't have much industry of its own. During the reign of King John V, gold also paid for beautiful Baroque buildings, like the Convent of Mafra. Besides gold, diamond deposits were found in 1729 near the village of Tijuco, now Diamantina. A famous person from this time was Xica da Silva, an enslaved woman who had a relationship with a Portuguese official. They had thirteen children, and she became a rich woman.

In the hilly landscape of Minas Gerais, gold was found in riverbeds. It was extracted using simple tools like pans. Most of the gold extraction was done by enslaved people. The gold industry brought hundreds of thousands of Africans to Brazil as slaves. The Portuguese king allowed private individuals to extract gold, but they had to send one-fifth (20%) of it to the government as a tax, called the quinto. To stop smuggling and collect the quinto, the government ordered all gold to be melted into bars in special "Casting Houses" (Casas de Fundição) in 1725. They also sent armies to the region to keep order and oversee mining. The quinto tax was very unpopular. Gold was often hidden from authorities. This tax contributed to rebellions like the Levante de Vila Rica in 1720 and the Inconfidência Mineira in 1789.

Many historians believe that much of the gold mined in Brazil during the 1700s ended up in Britain. This was because of a trade agreement called the Methuen Treaty between Portugal and Britain. This treaty meant that British wool cloth could enter Portugal tax-free. In return, Portuguese wine exported to Britain had lower taxes. While Port wine was popular in Britain, cloth was a much bigger part of the trade. So, Portugal ended up owing money to Britain.

The large number of adventurers coming to Minas Gerais led to the founding of several settlements. The first were created in 1711: Vila Rica de Ouro Preto, Sabará, and Mariana. Others followed, like São João del Rei (1713) and Tiradentes (1717). Unlike other parts of colonial Brazil, people in Minas Gerais mostly settled in villages instead of the countryside.

In 1763, the capital of colonial Brazil moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. Rio was closer to the mining region and had a harbor to ship the gold to Europe.

According to historian Maria Marcílio, Portugal had about two million people in 1700. During the 1700s, about 400,000 people moved to Brazil, even though the king tried to stop them. Gold production decreased towards the end of the 1700s. This led to a period of slower growth in the Brazilian interior.

Colonizing the South

To expand Brazil's borders and profit from the silver mines in Potosí, the Portuguese government ordered Governor Manuel Lobo to build a settlement on the River Plate. This area legally belonged to Spain. In 1679, Manuel Lobo founded Colonia del Sacramento across from Buenos Aires. This fortified settlement quickly became an important place for illegal trade between Spanish and Portuguese colonies. Spain and Portugal fought over this area many times.

Besides Colonia de Sacramento, several settlements were built in Southern Brazil in the late 1600s and 1700s. Some were settled by farmers from the Azores Islands. Towns founded during this time include Curitiba (1668), Florianópolis (1675), and Porto Alegre (1742). These towns helped Portugal keep strong control over southern Brazil.

Conflicts over the southern borders led to the Treaty of Madrid (1750). In this treaty, Spain and Portugal agreed to expand Brazil significantly to the southwest. Colonia de Sacramento was given to Spain. In return, Portugal received the territories of São Miguel das Missões, a region with Jesuit missions for the Guaraní natives. The Jesuits and Guaraní resisted, leading to the Guaraní War (1756). Portuguese and Spanish troops destroyed the missions. Colonia de Sacramento changed hands several times until 1777, when it was finally taken by the Spanish governor of Buenos Aires.

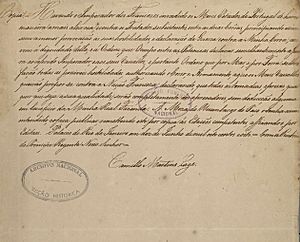

The Inconfidência Mineira: A Fight for Freedom

In 1788-1789, Minas Gerais was the site of the most important plot against colonial rule. It was called the Inconfidência Mineira. This conspiracy was inspired by the ideas of French thinkers from the Age of Enlightenment and the successful American Revolution of 1776. The plotters were mostly wealthy white people from Minas Gerais. Many had studied in Europe and had large debts to the colonial government. Gold production was declining, and the Portuguese government planned to force everyone to pay their debts. This was a main reason for the conspiracy.

The plotters wanted to create a Republic where the leader would be chosen by democratic elections. Their capital would be São João del Rei, and Ouro Preto would become a university town. They wanted to keep the existing social structure, including private property and slavery.

The Portuguese colonial government discovered the plot in 1789, before the rebellion could start. Eleven of the conspirators were sent away to Portuguese colonies in Angola. But Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, known as Tiradentes, was sentenced to death. Tiradentes was hanged in Rio de Janeiro in 1792. He later became a symbol of Brazil's fight for independence and freedom from Portuguese rule.

The Inconfidência Mineira was not the only rebellion in colonial Brazil. Later, in 1798, there was the Inconfidência Baiana in Salvador. This event involved more common people. Four people were hanged, and 41 were jailed. The members included enslaved people, middle-class people, and even some landowners.

Colonial Changes to Brazil's Environment

Colonial practices destroyed much of Brazil's forests. This happened partly because colonists saw nature as just a collection of resources to be used, without much value on its own.

Mining practices greatly harmed the land. To get gold, large parts of the forest on hillsides were burned. About 4,000 square kilometers of the Atlantic Forest region were cleared for mining. This left the land "bald and deserted." This massive destruction was a result of the colonial focus on taking resources without thinking about the future.

As the gold rush slowed down, many Portuguese colonists stopped mining and started farming and raising animals. Farming pushed inland expansion even further into the Brazilian forest. The colonists started a trend that had big, lasting effects. Their farming methods greatly changed Brazil's environment. The Portuguese colonists believed farming was a good way to "tame" the wild frontier. They encouraged mixed-race people, and native people to leave the forest and start farming.

However, colonial farming methods were not sustainable. They used up the land quickly. Farmers often used slash-and-burn practices. They also struggled with leaf-cutting ants, called saúva. These ants were hard to get rid of. Instead of fighting the ants, colonists would often abandon their fields and clear new ones by burning. This only made the problem worse over time.

This environmental change was very different from how Brazilian native people managed the land. Native people generally didn't harm the environment much. They lived in small communities and had sustainable ways of farming, hunting, and gathering. They focused on keeping the land productive for a long time.

The introduction of European animals—cattle, horses, and pigs—also changed the land a lot. Native plants in Brazil's interior died from being trampled by cattle. They were replaced by grasses that could handle such abuse. Cattle also overgrazed fertile fields, killing plants. Harmful, poisonous plants sometimes replaced these. Colonists tried to get rid of these unwanted plants by burning large pastures. This killed many small animals and damaged the soil.

Cattle Raising in Colonial Brazil

Like farming, the mining economy shaped the cattle industry. Beef was a main food for miners. Cattle raising spread from Sao Paulo to other plains.

Cattle were not well cared for. They weren't given extra food, and branding was often ignored. Many cattle died during the dry season, and it took years for them to reach a good weight for selling. Salt was used as a poor food supplement, making salted meats and dairy products expensive. Cattle also suffered from parasites and ticks. To escape pests, they often moved into forest edges, harming those ecosystems. As mentioned, cattle raising changed the native landscape. Burning grasses to get rid of bad plants only worked for a short time. In the long run, it caused soil erosion and made pastures less nutritious. This led to unproductive cattle raising.

Historian Warren Dean points out how colonialism and capitalism led to the wasteful use of the Atlantic Forest. But he also warns that we shouldn't blame only colonialism and capitalism. He suggests that colonists sometimes resisted royal authority if it didn't serve their interests.

The Royal Court in Brazil (1808–1821)

The invasion of Portugal by Napoleon Bonaparte's French troops in 1807 caused big changes. Prince Regent João (who would become King João VI) was ruling Portugal for his mother, Queen Maria I. He ordered the Portuguese royal court to move to Brazil to avoid being captured. In January 1808, Prince João and his court arrived in Salvador. There, he signed a new rule that allowed Brazil to trade directly with "friendly nations" (like Britain). This was a huge change, as Brazil had only been allowed to trade with Portugal before.

In March 1808, the court arrived in Rio de Janeiro. In 1815, during the Congress of Vienna, Prince João created the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. This made Brazil equal in status to Portugal and gave it more independence.

In 1816, Queen Maria died, and Prince João became King João VI. His crowning ceremony was held in Rio de Janeiro in February 1818.

During his years in Brazil, King João took many important steps. He encouraged trade and industry. He allowed newspapers and books to be printed. He created two medical schools, military academies, and the first Bank of Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro, he also built a powder factory, a Botanical Garden, an art academy, and an opera house. All these actions greatly helped Brazil become more independent from Portugal. They made the later political separation between the two countries unavoidable.

Because the King was in Brazil and Brazil's economy was growing, Portugal faced a serious crisis. This forced João VI and the royal family to return to Portugal in 1821. A Liberal Revolution had started in Portugal in 1820. The royal governors there had been replaced by a revolutionary council. This council wanted the King to return and change Portugal into a constitutional monarchy. King João VI agreed and returned to Europe. Brazilian representatives were elected to join the discussions in Portugal.

João VI's son, Prince Pedro, stayed in Brazil. The Portuguese government demanded that Brazil return to being a colony and that Prince Pedro return to Portugal. But Prince Pedro, influenced by the Rio de Janeiro city council, refused to go back. This famous event is known as the Dia do Fico (January 9, 1822). Brazil gained its political independence on September 7, 1822. Prince Pedro was crowned emperor in Rio de Janeiro as Dom Pedro I. This ended 322 years of Portuguese rule over Brazil.

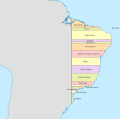

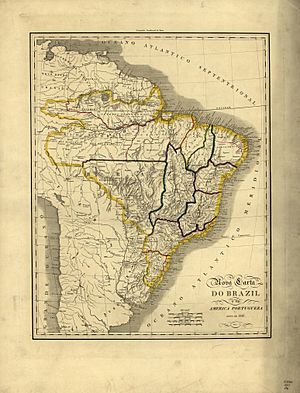

Territorial Evolution of Colonial Brazil

Administrative Changes Over Time

Here's how the way Brazil was governed changed during the colonial period:

- 1534–1549: Brazil was divided into private, self-governing areas called hereditary captaincies.

- 1549: The Portuguese King abolished the private captaincy system. The existing captaincies became part of a single Crown colony, the Governorate General of Brazil.

- 1549–1572, 1578–1607, 1613–1621: The unified Governorate General of Brazil existed, with its capital in Salvador.

- 1572–1578 and 1607–1613: The colony was split into two separate Governorates: Bahia (North) and Rio de Janeiro (South).

- 1621: The Governorate General of Brazil became known as the State of Brazil. A northern part of Brazil became a separate colony, the State of Maranhão.

- 1652: The State of Maranhão was briefly added back to the State of Brazil, reuniting the colony.

- 1654: Maranhão was separated again, and the Captaincy of Grão-Pará was also split off. These two areas formed a new state, the State of Maranhão and Grão-Pará.

- 1751: The State of Maranhão and Grão-Pará was renamed the State of Grão-Pará and Maranhão. Its capital moved to Belém.

- 1763: The capital of the State of Brazil moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. The King's representative was officially called a Viceroy.

- 1772: The State of Grão-Pará and Maranhão was split into two: the State of Grão-Pará and Rio Negro, and the State of Maranhão and Piauí.

- 1775: All Portuguese territories in South America were reunited under the State of Brazil, with Rio de Janeiro as the capital.

- 1808: The Portuguese Royal Court moved to Brazil due to the Napoleonic Wars. The Prince Regent took direct control, and Brazil became the temporary seat of the entire Portuguese Empire.

- 1815: Brazil stopped being a colony. It was elevated to a kingdom, forming the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. This marked the official end of the colonial era.

- 1822: Brazil declared its independence from the United Kingdom and became the Empire of Brazil. Portugal recognized this separation in 1825.

After 1815, the former captaincies became provinces within the new Kingdom, and later, provinces of the independent Empire of Brazil.

|

See also

In Spanish: Colonización de Brasil para niños

In Spanish: Colonización de Brasil para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |