Ashanti Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ashanti Empire

Asanteman (Asante Twi)

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||

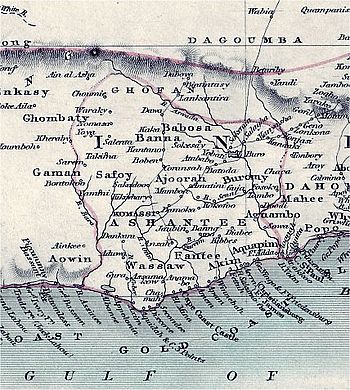

Map of the Ashanti Empire

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | State union | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Kumasi | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ashanti (Twi) (official) | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Initially Akan religion, later also Christianity | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

|

• 1670–1717 (first king)

|

Osei Tutu | ||||||||||||

|

• 1888–1896 (13th king of the indep. Ashanti Kingdom)

|

Prempeh I | ||||||||||||

|

• 1931–1957 (last king of the indep. Ashanti Kingdom)

|

Prempeh II | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Asante Kotoko (Council of Kumasi) and the Asantemanhyiamu (National Assembly) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

1701 | ||||||||||||

|

• Independence from Denkyira

|

1701 | ||||||||||||

|

• Annexed to form a British colony named Ashanti

|

1901 | ||||||||||||

|

• Self-rule

|

1935 | ||||||||||||

|

• State union as Ashanti Region with Ghana

|

1957 | ||||||||||||

|

• State union

|

Present | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 259,000 km2 (100,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

|

•

|

3,000,000 | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Ghana Ivory Coast Togo |

||||||||||||

The Asante Empire (also called Ashanti) was a powerful Akan kingdom in West Africa. It existed from 1701 to 1901 in what is now Ghana. At its largest, the empire stretched across much of modern-day Ghana. It also included parts of Ivory Coast and Togo.

The Asante Empire was known for its strong army, great wealth, and unique culture. Many historical records about it were written by Europeans.

In the late 1600s, the Ashanti king Osei Tutu and his advisor Okomfo Anokye founded the Ashanti Kingdom. They used the Golden Stool of Asante as a symbol to unite the people. In 1701, the Ashanti army defeated the Denkyira kingdom. This victory gave the Ashanti access to trade with Europeans along the coast. The empire's economy relied heavily on trading gold and captives.

The Ashanti army was very successful. They won many wars against neighboring kingdoms. They even defeated the British Empire in some of the early Anglo-Ashanti Wars. However, after the final war, the British took over. The Ashanti Empire became part of the Gold Coast colony in 1902.

Today, the Ashanti Kingdom still exists as a traditional state within the Republic of Ghana. The current king is Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Asantehene. The Ashanti Kingdom is home to Lake Bosumtwi, Ghana's only natural lake. Its economy today comes from trading gold, cocoa, and kola nuts, as well as agriculture.

Contents

Name and Early History

The name Asante means "because of war." It comes from the Twi words ɔsa (war) and nti (because of). This name shows that the kingdom was formed to fight the Denkyira kingdom.

The name "Ashanti" came from British reports. They wrote down "Asante" as they heard it, which sounded like as-hanti. Over time, the hyphen was dropped, and "Ashanti" became the common spelling.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries AD, the Akan people moved into the forest areas of Southern Ghana. They formed several Akan states. Before Europeans arrived, the Ashanti Kingdom traded a lot with other African states. This was thanks to their rich gold mines. When gold mines in other areas became less productive, the Ashanti Kingdom grew more important in the gold trade.

History of the Empire

How the Kingdom Started

Ashanti groups were first organized into clans, each led by a chief called an Omanhene. The Oyoko clan settled in the forest region and built a center at Kumasi. The Ashanti were under the control of the Denkyira kingdom. But in the mid-1600s, Chief Oti Akenten of the Oyoko clan began uniting the Ashanti clans. They wanted to fight against the Denkyira.

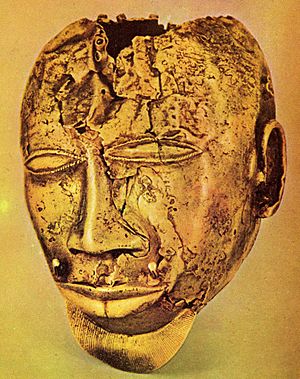

The Golden Stool (Sika dwa) helped unite the Ashanti. Legend says that before fighting Denkyira, all the clan heads met. During this meeting, the Golden Stool floated down from the sky and landed on Osei Tutu I's lap. Okomfo Anokye, Osei Tutu's advisor, declared the stool a symbol of the new Ashanti Union. Everyone swore loyalty to the stool and to Osei Tutu as the Asantehene (King). The Ashanti then defeated Denkyira. The Golden Stool is still sacred today. It is believed to hold the Sunsum—the spirit or soul of the Ashanti people.

Becoming Independent

In the 1670s, Osei Kofi Tutu I of the Oyoko clan began to quickly unite the Akan people. He used both diplomacy and warfare. King Osei Tutu I and his advisor, Okomfo Anokye, led Ashanti city-states against the Denkyira. The Ashanti Kingdom completely defeated them at the Battle of Feyiase. This led to their independence in 1701.

After this victory, King Osei Tutu and Okomfo Anokye convinced other Ashanti city-states to join them. They made Kumasi, the Ashanti capital, the main center. From the start, they aimed to expand their empire.

Growth Under Osei Tutu

Osei Tutu saw the strength in uniting the Akan states. He made the government more centralized. He also expanded the power of the justice system. This group of small city-states grew into a large kingdom and then an empire. New areas that were conquered could either join the empire or become states that paid tribute. Opoku Ware I, Osei Tutu's successor, expanded the empire even further. It eventually covered much of what is now Ghana.

Contact with Europeans

Europeans first met the Ashanti on the coast of Africa in the 1400s. This led to trade in gold, ivory, and other goods with the Portuguese. In 1817, an Englishman named Thomas Edward Bowdich visited Kumasi. He was very impressed by the kingdom. He wrote a book about his visit when he returned to England.

Relations with the British

From 1824 to 1899, there were five Anglo-Ashanti wars between the Ashanti Empire and Great Britain. The British lost or made peace in some of these wars. The wars happened because the Ashanti wanted to control the coastal areas of Ghana. Coastal people like the Fante relied on British protection from Ashanti attacks.

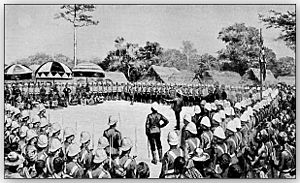

In December 1895, the British sent an army from Cape Coast. They arrived in Kumasi in January 1896. The Asantehene told the Ashanti not to fight the British. He feared what Britain would do if there was violence. Soon after, Britain took over the Ashanti lands. They made it the Ashanti Crown Colony in 1901. The Asantehene Prempeh I and other Ashanti leaders were sent away to the Seychelles.

Uprisings and Self-Rule

As a final act of resistance, the remaining Ashanti leaders fought against the British in Kumasi. This fight was led by Queen Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen-Mother of Ejisu. From March to September 1900, the Ashanti and British fought in the War of the Golden Stool. The British won, and Queen Yaa Asantewaa was also sent into exile.

In January 1902, Britain officially made the Ashanti Kingdom a protectorate. However, the Ashanti Kingdom regained its self-rule on January 31, 1935. Asante King Prempeh II was restored to power in 1957. The Ashanti Kingdom then joined Ghana as a state when Ghana became independent from the United Kingdom.

Government and Leadership

The Ashanti government was very organized. It had a system of leaders from families up to the king. The smallest unit was the family, led by the Abusua Panyin. Several villages formed a division, led by an Ohene. Divisions then formed states, led by an Omanhene. Finally, all Ashanti states together formed the Ashanti Empire, with the Asantehene as their king.

The Ashanti government in Kumasi had a complex system. It had different departments, like ministries, to manage state affairs. There was even a Foreign Office that handled relations with other countries. This showed how advanced their government was.

The Asantehene

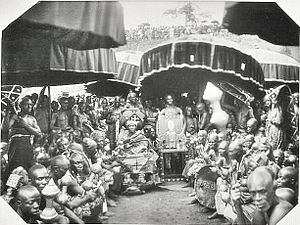

At the top of the Ashanti government was the Asantehene, the King of Ashanti. Each Asantehene was crowned on the sacred Golden Stool. This stool symbolized the king's power. Osei Kwadwo (1764–1777) started a system where officials were chosen based on their skills, not just their birth.

The Asantehene had great power. But he had to share legislative and executive powers with the government officials. However, only the Asantehene could order a death sentence for crimes. During wartime, the King was the Supreme Commander of the Ashanti army. Each part of the empire also had to send annual tribute to Kumasi.

The Asantehene was also the King of Kumasi, the capital. He was chosen in a similar way to other chiefs. Every chief swore loyalty to the one above him, all the way up to the Asantehene. The Asantehene, in turn, swore loyalty to the entire state.

Elders and chiefs from other divisions limited the King's power. This created a system of checks and balances. The Asantehene was a symbol of the nation. He was seen as a link between the people and their ancestors. If the king did something the elders or people did not approve of, he could be removed from power.

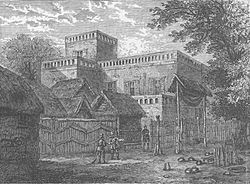

King's Residences

The current home of the Asantehene is the Manhyia Palace. The British built it in 1925 and gave it to Prempeh I when he returned from exile. The original palace in Kumasi was burned by the British in 1875. European visitors described it as a huge, beautiful building with many courts and detailed decorations.

Asanteman Council

This council helped the Asantehene and advised him. It was made up of Amanhene (paramount chiefs) from different Ashanti states. It also included other chiefs. The Asantehene could not ignore the council's decisions. If he did, he could be removed from his throne.

Amanhene

The Ashanti Empire had metropolitan (main) and provincial (other) states. The metropolitan states were made up of Ashanti citizens. The provincial states were other kingdoms that joined the empire. Each metropolitan Ashanti state was led by an Amanhene, or paramount chief. These chiefs were the main rulers of their own states. They had executive, legislative, and judicial powers.

Ohene

The Ohene were divisional chiefs under the Amanhene. Their main job was to advise the Amanhene. These chiefs led different divisions, which were groups of villages. Examples include Krontihene and Nifahene.

Odikuro

Every village in Asante had a chief called an Odikro. The Odikro was responsible for keeping law and order. He also connected the people to their ancestors and gods. The Odikro led the village council.

Queen Mother

The queen or Ohenemaa was a very important person in Ashanti politics. She was the most powerful woman in the Empire. She had to be consulted when choosing a chief or the king. She also settled disputes among women. She was involved in making decisions with the Council of Elders and chiefs. She participated in legal and legislative processes. She also helped decide about war and land distribution.

Obirempon

Successful business people who became very wealthy and did heroic deeds were called "Abirempon" or "Obirempon." This means "big men." By the 18th and 19th centuries, this title was given to those whose trade benefited the whole state. They had significant power in their regions. They handled administration and economic matters. They also acted as the main judge in their area.

Kotoko Council

The Kotoko was a government council in the Ashanti Empire. It balanced the power of the king's council of elders. This council formed the law-making body of the Ashanti government. It included the Asantehene, the Queen Mother, and the state chiefs with their ministers.

Choosing Leaders

The election of kings and the Asantehene followed a specific process. The oldest female in the royal family would suggest eligible men. She would then talk to the elders of that family line. The final candidate was then chosen. This choice was sent to a council of elders, who represented other families in the town or district.

The elders then presented the candidate to all the people. If the citizens did not approve, the process started over. Once chosen, the new kings were crowned by the elders. The elders would remind them of their duties. The new king swore an oath to the Earth Goddess and his ancestors. He promised to serve the state honorably.

The chosen king had a grand ceremony with much celebration. He held great power, including the ability to make life-or-death judgments. However, his rule was not absolute. The king was sacred once on the stool. He was seen as a holy link between the people and their ancestors. His power depended on listening to the advice of the Council of Elders.

Removing a King

Ashanti kings who broke their promises made during their crowning could be removed by the Kingmakers. For example, if a king punished people unfairly or was found to be corrupt, he would be removed. Once removed, he lost his sacred status and all his powers. He would lose his position as administrator, judge, and military commander. He also lost his royal items like the stool and swords. However, he remained a member of the royal family. One king, Kusi Obodom, was removed after a failed invasion.

Justice System

The Ashanti justice system was deeply connected to their religion. They saw crimes as sins that disrespected ancestors. If a chief or king did not punish such acts, it was believed to anger the ancestors and gods. This could lead to the chief or king being removed. Some serious crimes could result in death, but this was rare. More often, people were banished or imprisoned.

The King usually decided on or changed all death sentences. These changes could happen through payment or gifts. These payments were seen as income for the state. The Ashanti disliked murder. In a murder trial, it had to be proven if the act was intentional. If it was an accident, the killer paid money to the victim's family. People with mental illness could not be executed, except for murder or insulting the King. Serious crimes included murder, attacking a chief, or insulting the court or King.

Insulting the King was a very serious act. It was believed to bring harm to him and could lead to death. People who practiced harmful witchcraft were also executed.

Usually, families settled disputes among themselves. But serious disputes could be brought to a chief's court. The King's Court was the final court for sentencing. Only the King could order the death penalty. In court, people spoke fully about their case. Anyone present could ask questions. If a verdict wasn't reached, a special witness would be called. If there was only one witness, their sworn oath was believed to be true. Cases without witnesses, like sorcery, were settled by trials like drinking a special liquid.

The Ashanti believed that honoring ancestors was key to their moral system. This belief guided their government's rules. The justice system focused on good behavior and harmony among people. Rules were believed to come from Nyame (the Supreme God) and the ancestors. People were expected to behave according to these rules.

Geography

The Ashanti Empire was one of several states along the West African coast. The Ashanti had mountains and produced a lot of agricultural goods. The southern part of the empire had moist forests. The northern part had a savanna, with short, fire-resistant trees. Rivers and streams in the savanna also had forests along their banks. The soils were mainly forest soils in the south and savanna soils in the north.

The empire had many animals like hens, sheep, goats, ducks, turkeys, rabbits, guineafowl, fish, and porcupines. The porcupine became the national symbol. There were also many useful trees and plants. These animals and plants were often found around Ashanti homes.

Between 1700 and 1715, Osei Tutu I conquered nearby states like Twifo and Wassa. His successor, Osei Bonsu, continued to expand the empire. He brought in Akan states like Tekyiman and Akyem between 1720 and 1750. From 1730 to 1770, the empire expanded north into the savanna states. By 1816, the Ashanti had also taken control of coastal states like the Fante Confederacy.

Economy

Resources

The Ashanti Kingdom was rich in river gold, cocoa, and kola nuts. The Ashanti soon began trading with the Portuguese at the coastal fort of Sao Jorge da Mina (later Elmina). They also traded with the Songhai and the Hausa states.

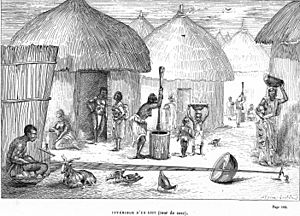

Agriculture

The Ashanti prepared their fields by burning them before the rainy season. They used an iron hoe for farming. Fields were left to rest for a few years after two to four years of growing crops. They grew plantains, yams, manioc, corn, sweet potatoes, millet, beans, onions, peanuts, tomatoes, and many fruits. Manioc and corn came from the New World during the Atlantic slave trade. Many crops could be harvested twice a year. Cassava (manioc) provided a starchy root after two years of growth. The Ashanti made beer from palm wine, maize, and millet. They also used palm oil for cooking and other household needs.

Communication

The Ashanti invented the Fontomfrom, a "talking drum." They also invented the Akan Drum. They could send messages over 200 miles (320 km) as fast as a telegraph. The Asante dialect (Twi) and Akan language are tonal. This means the tone of voice changes the meaning of words. The drums copied these tones, so trained listeners could understand full phrases.

The Ashanti easily understood the messages from these "talking drums." Standard messages called for meetings, warned of danger, or announced the death of important people. Some drums were used for proverbs and ceremonies.

Population and Cities

The Ashanti Kingdom slowly became more centralized. In the early 1800s, the Asantehene used yearly tributes to create a permanent army with rifles. This allowed for tighter control of the kingdom. The Ashanti Kingdom was one of the most centralized states in Africa south of the Sahara. Osei Tutu and the kings after him worked to unite the people politically and culturally. The union reached its full size by 1750. It remained an alliance of several large city-states that recognized the ruler of Kumasi, the Asantehene. The Ashanti Kingdom had many people living in it. This allowed for the creation of large urban centers. The Ashanti controlled over 250,000 square kilometers and ruled about 3 million people.

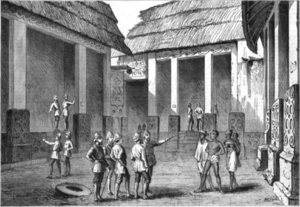

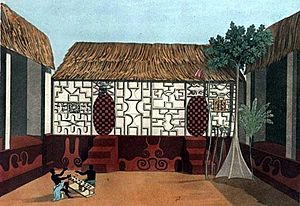

Architecture

The traditional Ashanti buildings are the only remaining examples of Ashanti architecture. They were built with a timber frame filled with clay and covered with thatched leaves. The surviving buildings are shrines, but many other buildings like palaces and houses for wealthy people had the same style. The Ashanti Empire also built mausoleums to house the tombs of several Ashanti leaders.

Most houses, whether for people or for gods, had four separate rectangular rooms around an open courtyard. The inner corners of the buildings were connected by screen walls. These walls could be adjusted to fit the layout. Usually, three buildings were open to the courtyard. The fourth was partly enclosed by a door and windows or open-work screens. Thomas Bowdich described the Ashanti Palace in 1817 as having beautiful decorations. He compared its squares to the front of an Italian theater stage.

Roads and Communication

The empire had a network of well-maintained roads. These roads connected the Ashanti mainland to the Niger River and other trade cities. English visitors to Kumasi in the 1800s noted that the capital was divided into 77 areas with 77 main streets. One street was 100 yards wide. Many houses, especially near the king's stone palace, were two stories tall. They had indoor plumbing with toilets flushed by boiling water.

Along Ashanti roads, there were Nkwansrafo, or road wardens. They acted as highway police. They checked the movement of traders and strangers. They also collected tolls from traders. The Ashanti Empire also built bridges over water for transport. Asantehene Kwaku Dua I ordered his engineers to build proper bridges over streams in the main cities. A visitor in the 1800s described how they built bridges using strong posts, beams, and poles covered with earth.

Police and Military

Police Force

The Asantehene inherited his position from his queen mother. He was helped in Kumasi by a civil service of talented men. These men were skilled in trade, diplomacy, and the military. The head of this service was called the Gyaasehene. Men from the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan, and Europe worked in the Ashanti civil service. All were chosen by the Asantehene.

In the main Ashanti areas, several police forces kept law and order. In Kumasi, a uniformed police force, known for their long hair, made sure no one entered or left the city without government permission. The ankobia, or special police, were the empire's special forces and the Asantehene's bodyguards. They also gathered intelligence and stopped rebellions. For most of the 1800s and into the 1900s, the Ashanti state remained powerful.

Military Strength

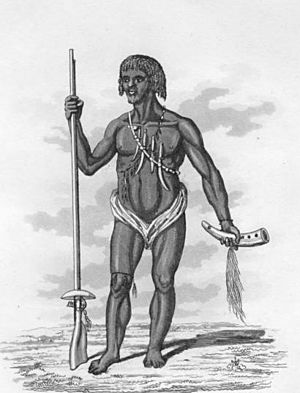

The Ashanti armies were very effective. They helped the empire expand for a long time and resist European colonization. They mainly used firearms. But their organization and leadership were also very important to their success. The Ashanti army included troops from conquered peoples. Despite facing revolts, the "golden stool" and the national army helped keep the empire united.

The total potential strength of the army was between 80,000 and 200,000 soldiers. This made the Ashanti army larger than the famous Zulu army. Tens of thousands of soldiers were usually available. The army was organized with an advance guard, main body, rear guard, and two flanking wings. This made them flexible in the forest areas where they usually fought. Horses were known in Kumasi, but they couldn't survive in the tsetse fly-infested forest in the south. So, there was no cavalry. Ashanti officers rode horses, but not into battle. The army used ambushes and maneuvers on the wings. Uniquely among African armies, the Ashanti had medical units to support their fighters. This force helped the empire grow and defeat the British in several battles.

Ashanti blacksmiths could repair firearms. They also sometimes remade barrels, locks, and stocks for guns.

Ashanti Wars

From 1806 to 1896, the Ashanti Kingdom was often at war. These wars were for expansion or defense. The Ashanti's victories against other African forces made them the strongest power in the region. Their impressive performance against the British also earned them respect from European powers.

Ashanti–Fante War

In 1806, the Ashanti chased two rebel leaders into Fante territory on the coast. The British refused to give up the rebels. This led to an Ashanti attack. The British eventually handed over one rebel. In 1807, disputes with the Fante led to the Ashanti–Fante War. The Ashanti won this war under Asantehene Osei Bonsu.

Ga–Fante War

In the 1811 Ga–Fante War, the Ashanti and Ga fought against the Fante, Akwapim, and Akim states. The Ashanti army defeated their enemies. They pushed them towards the Akwapim hills. However, the Ashanti stopped their pursuit after capturing a British fort. They then focused on establishing their power on the coast.

Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War

In 1814, the Ashanti invaded the Gold Coast to gain access to European traders. In the Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War, they faced the Akim–Akwapim alliance. After several battles, the Akim–Akwapim alliance was defeated. They became states that paid tribute to the Ashanti. The Ashanti Kingdom then controlled the area from the midlands to the coast.

Anglo-Ashanti Wars

First Anglo-Ashanti War

The first of the Anglo-Ashanti wars happened in 1823. The Ashanti Kingdom fought against the British Empire on the coast. The conflict began when Sir Charles MacCarthy led an invading force. The Ashanti defeated them and moved to the coast. But disease forced them back. The Ashanti were so successful that in 1826, they again moved to the coast. They fought well against larger British allied forces. However, the British used rockets, which made the Ashanti army retreat. In 1831, a treaty led to 30 years of peace. The Pra River was set as the border.

Second Anglo-Ashanti War

Except for a few small fights in 1853 and 1854, peace lasted for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large Ashanti group crossed the river chasing a fugitive. There was fighting and casualties on both sides. The war ended in 1864 as a stalemate. Both sides lost more men to sickness than to fighting.

Third Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1869, a European missionary family was taken to Kumasi. They were treated well, but their capture was used as an excuse for war in 1873. Britain also took control of Ashanti land that the Dutch had claimed. The Ashanti invaded the new British protectorate. General Wolseley was sent against the Ashanti. This was a modern war with press coverage. The British government allowed arms manufacturers to sell weapons to both sides.

All Ashanti attempts to negotiate were ignored. Wolseley led 2,500 British troops and several thousand African troops to Kumasi. The capital was briefly taken over. The British were impressed by the palace's size and contents, including "rows of books in many languages." The Ashanti had left the capital after a bloody war. The British then burned it.

The British and their allies suffered many casualties. But the British firepower was too strong for the Ashanti. The Asantehene signed a treaty in July 1874 to end the war.

Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1895, the Ashanti refused an offer to become a British protectorate. The British wanted to conquer the Ashanti Kingdom to keep French and other European forces out of its gold-rich territory. So, Britain started the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1895. They claimed it was because the Asante monarch failed to pay fines from the 1874 war. The British won, and the Ashanti Kingdom was forced to sign a treaty.

Culture and Society

Family Life

Family status was mostly about politics. The royal family was usually at the top. Below them were the families of the chiefs of different areas. In each chiefdom, a specific female line provided the chief. A group of men eligible for the position would elect the chief.

The typical Ashanti family was extended and matrilineal. This means children belonged to their mother's clan. A mother's brother was the legal guardian of her children. The father had fewer legal duties for his children, but he made sure they were well. Women also had the right to start a divorce.

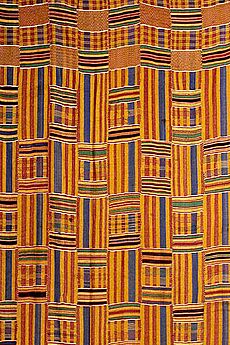

Clothing

Important people wore silk. Ordinary Ashanti people wore cotton. Clothes showed a person's rank in society. Colors also had different meanings. White was worn by ordinary people after winning a court case. Dark colors were worn for funerals or mourning. There were rules that limited certain Kente designs to the nobility. Some cotton or silk patterns on Kente cloth were only for the king. They could only be worn with his permission.

Education and Children

Education in the Ashanti Kingdom was provided by Ashanti and foreign scholars. Ashanti people often went to schools in Europe for higher education.

Ashanti parents were generally tolerant. Childhood was seen as a happy time. Children were not held responsible for their actions until after puberty. A child was seen as harmless. So, the usual elaborate funeral rites were not as lavish for children.

The Ashanti loved twins born into the royal family. They were seen as a sign of good fortune. Boy twins usually joined the army. Girl twins could become wives of the King. If twins were a boy and a girl, they did not have a special career path. Women who had triplets were highly honored because three was a lucky number. Special ceremonies happened for the third, sixth, and ninth child. The fifth child was considered unlucky. Families with many children were respected.

Adinkra Symbols

The Ashanti used Adinkra symbols in their daily lives. These symbols were used for decoration, logos, art, sculpture, and pottery.

Healthcare and Death

Sickness and death were important events in the kingdom. A traditional herbalist would try to find the supernatural cause of an illness. They would treat it with herbal medicines.

People disliked being alone when sick. They wanted someone to perform a special rite before they collapsed. The family dressed the deceased in their best clothes. They also put gold dust (money for the afterlife), ornaments, and food with them for their journey. The body was usually buried within 24 hours. Until then, the funeral party would dance, drum, and fire guns. Relatives would wail. This was because the Ashanti believed death was a part of life, not something to be sad about. They believed in an afterlife and that families would reunite with ancestors. Funeral rites for a king were much more elaborate and involved the whole kingdom.

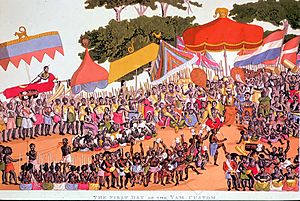

Ceremonies

The greatest and most frequent Ashanti ceremonies honored the spirits of past rulers. They offered food and drink, asking for good fortune. This ceremony was called the Adae. The day before the Adae, Akan drums announced the upcoming ceremonies. The chief priest led the Adae in the stool house, where ancestors were honored. The priest offered food and drink to each ancestor. The public ceremony happened outdoors, with everyone dancing. Musicians chanted ritual phrases. The talking drums praised the chief and ancestors.

The Odwera was another large ceremony. It happened in September and lasted one to two weeks. It was a time to cleanse society of wrongdoing. It also purified the shrines of ancestors and gods. After a sacrifice and feast, a new year began. Everyone was considered clean, strong, and healthy.

Slavery in the Empire

Slavery was a historical practice in the Ashanti Empire. Slaves were often captives from wars. The Ashanti Empire was a major slave-owning state and a large trader in the region for the Atlantic slave trade. The treatment of slaves varied. Some could gain wealth and marry into their master's family. Others were sacrificed in funeral ceremonies. The Ashanti believed slaves would follow their masters into the afterlife. Slaves could sometimes own other slaves. They could also ask for a new master if they felt they were being badly treated.

Modern Ashanti people say that slaves were rarely abused. They claim that people who abused slaves were looked down upon by society. They also point out that slaves were allowed to marry. If a master wanted to marry a female slave, he might. This was sometimes preferred over marrying a free woman. This was because children from a marriage to an enslaved woman could inherit some of the father's property and status. This arrangement was favored by some men because of the matrilineal system. Under this system, children belonged to their mother's clan. Her eldest brother was often the mentor for her children. Some Ashanti men felt more comfortable marrying an enslaved woman. She would not have a male relative to interfere if the couple argued. With an enslaved wife, the master had full control of their children, as she had no family in the community.

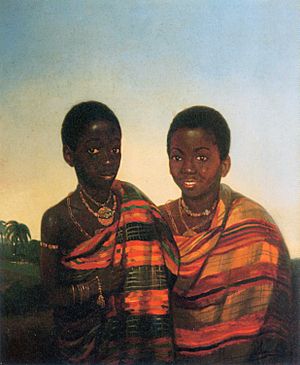

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Imperio asante para niños

In Spanish: Imperio asante para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |