Mali Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mali Empire

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1230–1672 | |||||||||||||||||

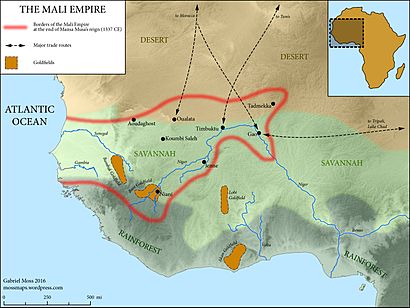

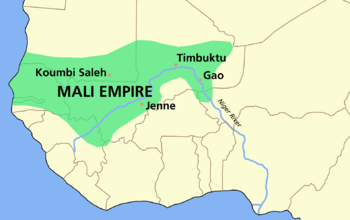

Extent of the Mali Empire (c. 1350)

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Identification disputed; possibly no fixed capital | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Mandinka, Fulani, Wolof, Bambara | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Mansa | |||||||||||||||||

|

• 1235–1255

|

Mari Djata I (first) | ||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 17th century

|

Mahmud IV (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Gbara | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassical Era to Early Modern Era | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 1230 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• State divided among emperor Mahmud Keita IV's sons

|

c. 1610 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Niani sacked and burned by the Bamana Empire

|

1672 | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 1250 | 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1380 | 1,100,000 km2 (420,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1500 | 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Gold dust (Salt, copper, silver and cowries were also common in the empire) |

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

The Mali Empire was a powerful empire in West Africa that lasted from about 1226 to 1670. It was started by a leader named Sundiata Keita. This empire became famous for how rich its rulers were, especially Mansa Musa. At its strongest, Mali was the largest empire in West Africa. It greatly influenced the culture of the area by spreading its language, laws, and customs.

The empire began as a small kingdom of the Mandinka people. It was located near the upper part of the Niger River. It grew bigger as the Ghana Empire became weaker and trade routes moved south. The early history of Mali is not very clear. We have different stories from Arab writers and from oral traditions. The first ruler we know a lot about is Sundiata Keita. He was a warrior prince who helped his people break free from the Sosso Empire. When Mali conquered Sosso around 1235, it became a major power.

After Sundiata Keita died around 1255, Mali's kings were called mansa. Around 1285, a former royal slave named Sakoura became emperor. He was one of Mali's strongest rulers and made the empire much larger. He traveled to Mecca but died on his way back home. Mansa Musa became king around 1312. He made a very famous trip to Mecca from 1324 to 1326. His gifts and spending of gold caused prices to go up in Egypt for many years.

Mansa Musa's nephew, Maghan I, took the throne in 1337. But his uncle Suleyman replaced him in 1341. During Suleyman's rule, a famous traveler named Ibn Battuta visited Mali. Suleyman's death marked the end of Mali's "Golden Age." After this, the empire slowly started to decline.

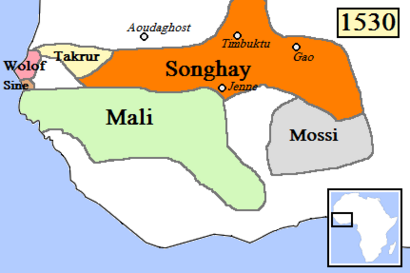

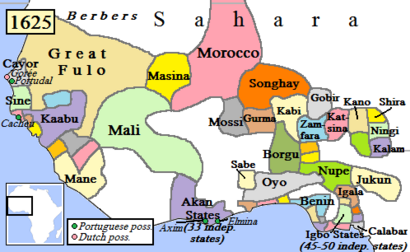

Even in the 15th century, Mali was still a large state. Travelers from Venice and Portugal confirmed that people in the Gambia area still followed the Mansa of Mali. By the early 16th century, Mali was still a big kingdom. However, other states like Great Fulo and the Songhai Empire began taking parts of Mali's land. In 1542, the Songhai attacked Mali's capital but could not conquer the empire. In the 17th century, the Bamana Empire attacked Mali. They burned the capital in 1670. After this, the Mali Empire quickly broke apart into smaller chiefdoms. The Keita family, who were the rulers, moved to the town of Kangaba. There, they became local leaders.

Contents

- Understanding the Name of Mali

- How We Know About Mali

- Where Was Mali?

- Mali's History

- How Mali Was Governed

- Mali's Economy

- Mali's Military Power

- Society and Culture

- Mali's Lasting Impact

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding the Name of Mali

The words Mali, Mandé, Manden, and Manding are all different ways to say the same word. They come from various languages and dialects. Medieval Arab writers wrote it as Mali. In the Fula language, it is also called Mali. In the Manding languages, which are spoken today where the Mali Empire used to be, the region is called Manden or Manding.

Old writings disagree about whether Mali was the name of a city or a region. Ibn Battuta, who visited the capital from 1352 to 1353, called it Mali. The 1375 Catalan Atlas map showed a "city of Melly" in West Africa. Leo Africanus also said the capital city was called Melli. However, other writers said Mali was the name of a province or a group of people. No matter how it started, the name Mali eventually referred to the entire empire.

Some people think the name Mali comes from the Mandé word for "hippopotamus." This animal was special to the Keita rulers. There's even a legend that Sundiata turned into a hippopotamus. But local people and experts don't agree with these ideas.

How We Know About Mali

Most of what we know about the Mali Empire comes from three main sources. These are 14th-century historians and travelers: Ibn Khaldun from Tunisia, Ibn Battuta from Morocco, and 16th-century traveler Leo Africanus. Another very important source is the Mandinka oral tradition. This history was passed down through generations by storytellers called griots.

One account is from Shihab al-Umari, a geographer who wrote around 1340. He got his information from Malians who were on their hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca. He heard directly from several people and also learned about Mansa Musa's visit.

Ibn Battuta visited Mali in 1352. He wrote the first eyewitness account of a West African kingdom. Other accounts before his were usually second-hand. Ibn Khaldun wrote in the early 15th century. These writings, though not very long, give us a good picture of the empire when it was at its strongest.

After Ibn Khaldun died in 1406, there are no more Arab writings about Mali until Leo Africanus wrote over a century later. Arab interest in Mali went down after the Songhai Empire took over the northern parts of Mali. For the later years of the Mali Empire, our main written sources are Portuguese accounts. These describe Mali's coastal areas and nearby societies.

Where Was Mali?

The Mali Empire started and was centered in the Manding region. This area is in what is now southern Mali and northeastern Guinea.

Mali's Vast Territory

The Mali Empire grew to its largest size under the Laye Keita mansas. One writer, Al-Umari, described the empire as being very large. It took eight months to travel from its coast to its eastern edge. He also said it was south of Marrakesh and mostly populated. Mali's land also stretched into the desert.

The empire covered almost all the land between the Sahara Desert and the coastal forests. It included parts of modern-day Senegal, southern Mauritania, Mali, northern Burkina Faso, western Niger, the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, and northern Ghana. By 1350, the empire covered about 1,240,000 square kilometers (478,819 square miles). It also had its largest population then, ruling over 400 cities, towns, and villages. At this time, only the Mongol Empire was larger.

Al-ʿUmari said Mali had fourteen provinces. Some of these names are spelled differently in various old writings. Some of the important provinces included:

- Ghana: This was the area of the former Ghana Empire.

- Takrur: Located on the Senegal River.

- Sanghana: A region around the mouth of the Senegal river.

- Kawkaw: This was the city of Gao. It was once an independent kingdom but became part of Mali. Later, it became the capital of the Songhai Empire.

- Mali: This was the capital province, which gave the empire its name.

Al-ʿUmari also mentioned that four Amazigh tribes were under Mali's rule. These tribes lived in different desert areas.

Finding the Capital City

Historians disagree about where the capital city of the Mali Empire was. Some think it was Niani, others say it was on the Niger River, or that it moved often. Some even believe there was no fixed capital. This confusion comes from old Arab writings that are hard to read, and different oral traditions.

Early European writers thought Niani, a city near the border of Guinea and Mali, was the capital for most of the empire's history. This idea became popular. However, archaeological digs in Niani have not found strong proof of a royal residence from Mali's golden age (14th century). This suggests Niani might have been less important during that time.

Many scholars now believe the Mali Empire might not have had a permanent "capital" like we think of today. Instead, the Mansa and his court would move around. So, Arab visitors might have called whatever major city the Mansa was in at the time the "capital." Some think the name given for the capital in Arabic sources, "bambi," meant "seat of government" in general, not a specific city. This idea of a moving capital was also seen in other empires, like in Ethiopia and the Holy Roman Empire.

Mali's History

In ancient times, early cities grew along the middle Niger River. By the 6th century AD, profitable trade across the Sahara Desert began. This trade involved gold, salt, and slaves, and it helped West Africa's great empires rise.

Before the Empire

There are a few early mentions of Mali in old Islamic writings. These include references to "Pene" and "Malal" around 1068. We also hear stories about an early ruler who became Muslim.

According to the oral traditions of the griots, the Keita family, who ruled Mali, came from Lawalo. He was said to be a son of Bilal, a loyal follower of the prophet Muhammad. However, this claim is not certain.

Hunters from the Ghana Empire were among the first Mandinka people in the Manding region. They founded the Mandinka hunter brotherhood. This area was known for its rich wildlife and thick forests. The Camara family is said to be the first to live in Manding. They founded the first villages there. Many Mandinka families today came from this region.

The Manden city-state of Ka-ba (today's Kangaba) was an important center. From at least the 11th century, Mandinka kings ruled Manden from Ka-ba. They were under the Ghana Empire. But these early rulers had little real power.

Ghana's control over Manden ended in the 12th century. The Kangaba province then split into twelve smaller kingdoms. Around 1140, the Sosso kingdom began conquering lands. By 1180, it had even taken over Ghana. In 1203, the Sosso king, Soumaoro Kanté, became very powerful. He was known for terrorizing Manden.

Sundiata Keita, The Lion King

His Early Life

According to the epic stories, Sundiata of the Keita family was born in the early 13th century. His father was Nare Fa, the ruler of Niani. Sundiata's mother was Sogolon Kédjou, a woman with a hunched back. The child was named Sundiata, which means "lion." In some accounts, he is called Mari Djata, where "Mari" means "Prince" and "Djata" means "lion."

It was said that Prince Sundiata would become a great conqueror. But he had a difficult start. Oral traditions say he couldn't walk until he was seven years old. However, once he could walk, he grew strong and respected. By then, his father had died. Even though his father wanted Sundiata to be king, his half-brother, Dankaran Touman, was crowned instead. Dankaran and his mother forced Sundiata and his family into exile. But soon, King Soumaoro attacked Niani, forcing Dankaran to flee.

After many years in exile, Sundiata was asked by a group from his home to come back. They begged him to fight the Sosso and free the Manden kingdoms.

War Against Soumaoro Kante

Sundiata led the armies of Mema, Wagadou, and the Mandinka city-states. They revolted against the Kaniaga Kingdom around 1234. The combined forces defeated the Sosso army at the Battle of Kirina around 1235. This victory led to the fall of the Kaniaga kingdom and the rise of the Mali Empire. After the win, King Soumaoro disappeared. Sundiata was declared "king of kings" and given the title "mansa." At 18, he gained control over all 12 kingdoms in an alliance that became the Mali Empire. He was crowned as Sundiata Keita, the first Mandinka emperor. This is how the Keita family began its rule.

Sundiata's Rule

During Mansa Sundiata Keita's rule, Mali conquered several important places. He didn't fight in battles himself after Kirina. But his generals kept expanding the empire, especially to the west. They reached the Gambia River. This made his empire larger than the Ghana Empire at its peak. When the fighting stopped, his empire stretched about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) from east to west. He added the goldfields of Wangara, making them the southern border. The northern trade towns of Oualata and Audaghost were also conquered. Wagadou and Mema became junior partners in the empire. Other regions like Bambougou and Kaabu were also added to Mali.

The Mali Empire's Golden Age

After Sundiata's death, there were some power struggles. But eventually, his son, Wali, became the next Mansa. Ibn Khaldun considered Wali one of Mali's greatest rulers. He went on the hajj during his reign.

Wali was followed by his brothers, Wati and Khalifa. Khalifa was overthrown and killed because he was cruel. Then, Abu Bakr, Sundiata's grandson through his daughter, became Mansa. After him, a court official named Sakura took power. Sakura brought stability to Mali. Under him, Mali gained new lands and trade with North Africa increased. He also went on the hajj. After Sakura, power returned to Sundiata's family.

Mansa Musa I: The Richest Man in History

Kankan Musa, known as Mansa Musa, likely became ruler around 1312. His time as Mansa is seen as Mali's golden age. He was one of the first truly religious Muslims to lead the empire. He tried to make Islam the religion of the nobles but didn't force it on everyone. He also made Eid al-Fitr celebrations a national event. He could read and write Arabic and was interested in the city of Timbuktu. He peacefully took control of Timbuktu in 1324. Mansa Musa helped turn Sankore into an Islamic university, where Islamic studies greatly grew.

Mansa Musa's most famous achievement was his pilgrimage to Mecca. It started in 1324 and ended in 1326. Stories vary about how many people and how much gold he took. But everyone agrees he had a huge group. He gave away so much gold and bought so many things that the value of gold in Egypt and Arabia dropped for twelve years. When he passed through Cairo, a historian noted that his group bought many expensive items. This caused the value of gold to fall.

Another account says Mansa Musa's pilgrimage included 12,000 slaves. They carried his belongings. He also brought 80 loads of gold dust, each weighing a lot. For long journeys, they used animals for transport. Sources suggest he used 100 elephants to carry gold and hundreds of camels for supplies.

Musa had to take out large loans in Cairo before returning home. It's unclear if this was to fix the gold's value or if he just ran out of money. Musa's hajj, especially his gold, got the attention of both the Islamic and Christian worlds. Because of this, Mali and Timbuktu appeared on 14th-century world maps.

While on his hajj, he met an architect named es-Saheli. Mansa Musa brought him back to Mali to make some cities more beautiful. Mosques were built in Gao and Timbuktu, along with impressive palaces. By the time Musa died in 1337, Mali controlled Taghazza, a salt-producing area in the north. This made the empire even richer.

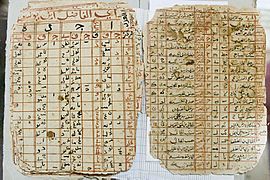

By the end of Mansa Musa's rule, Sankoré University had become a fully staffed university. It had one of the largest collections of books in Africa since the Library of Alexandria. Sankoré could hold 25,000 students and had about 1,000,000 manuscripts.

Mansa Musa was followed by his son, Maghan Keita I, in 1337. Maghan spent money carelessly. But the Mali Empire was strong enough to survive his poor rule. It then passed to Musa's brother, Souleyman Keita, in 1341.

Mansa Souleyman Keita

Mansa Souleyman Keita worked hard to fix Mali's finances. He became known for being careful with money. During his rule, there were some attacks from the Fula people. There was also a plot to overthrow him by the Queen and some army leaders. But Mansa Souleyman's generals fought off the attacks, and the Queen was jailed.

The Mansa also made a successful hajj. He kept in touch with Morocco and Egypt. He built a special platform where he held court and kept holy books from his pilgrimage.

The only major loss during his rule was the Dyolof province in Senegal. The Wolof people there formed their own state, the Jolof Empire, in the 1350s. Still, when Ibn Battuta visited Mali in 1352, he found a thriving civilization. Mansa Souleyman Keita died in 1360.

Later Rulers and Decline

After Souleyman, his son Camba Keita ruled for only nine months before being removed. Then, Mansa Mari Djata Keita II took the throne in 1360. He ruled harshly and almost made Mali go bankrupt with his spending. He died in 1374.

His brother, Mansa Musa Keita II, became ruler in 1374. He started to fix the empire's finances. However, he didn't have as much power as earlier mansas. His chief minister, Mari Djata, largely ran the empire. Around 1375, the Songhai people broke away from Mali's control. Still, when Mansa Musa Keita II died in 1387, Mali was financially stable. It still controlled most of its lands, except for Gao and Dyolof. Forty years after Mansa Musa I, the Mali Empire still covered about 1,100,000 square kilometers (424,712 square miles).

The last son of Maghan Keita I, Tenin Maghan Keita, became Mansa Maghan Keita II in 1387. He ruled for only two years and was removed in 1389. This marked the end of the main Keita family line of mansas.

The Empire's Final Years (1389–1545)

From 1389 onwards, Mali had many rulers whose origins are unclear. This is the least known time in Mali's history. It's clear that there was no steady family ruling the empire. Also, Mali slowly lost its northern and eastern lands to the rising Songhai Empire. Mali's economy also shifted from trans-Saharan trade to trade along the coast.

In the early 15th century, Mali was still strong enough to conquer new areas. But it also started losing important lands. In 1433–1434, Mali lost control of Timbuktu to the Tuareg people. Three years later, Oualata also fell.

After Musa Keita III died, his brother Gbèré Keita became emperor in the mid-15th century. He ruled when Mali first had contact with Portugal. In the 1450s, Portugal started sending raiding parties along the Gambian coast. The Gambia was still under Mali's control. A Venetian explorer noted that the Mali Empire was the most powerful force on the coast in 1454.

Despite its power in the west, Mali was losing control in the north and northeast. The new Songhai Empire conquered Mema, one of Mali's oldest lands, in 1465. It then took Timbuktu from the Tuareg in 1468.

Mansa Mahmud Keita II became king in 1481 during Mali's decline. His rule saw more losses of Mali's old lands. But it also brought more contact between Mali and Portuguese explorers along the coast. In 1481, Fula attacks began against Mali's Tekrur provinces.

The growing trade with Portugal led to exchanges of envoys. Mansa Mahmud Keita II met Portuguese envoys in 1487. The Mansa lost control of Jalo during this time. Meanwhile, Songhai took the salt mines of Taghazza in 1493. That same year, Mahmud II sent another envoy to Portugal, asking for help against the Fula. But Portugal decided not to get involved.

Songhai forces defeated a Mali general in 1502 and took the province of Diafunu. In 1514, the Denianke dynasty was formed in Tekrour. Soon, this new kingdom was fighting against Mali's remaining provinces.

In 1534, Mahmud III, the grandson of Mahmud II, met another Portuguese envoy. This envoy came because of the growing coastal trade and Mali's urgent need for military help against Songhai. But no help came, and Mali lost more lands. The date of Mahmud's death is not known.

In 1544 or 1545, a Songhai army attacked Mali's capital. They reportedly used the royal palace as a toilet. However, the Songhai did not keep control of the capital.

Mali's situation seemed to get better in the second half of the 16th century. Around 1550, Mali attacked Bighu to get back its gold. Songhai's control over some areas weakened by 1571. Mali might have regained some authority there. The breakup of the Wolof Empire also allowed Mali to regain control over some former subjects along the Gambia River by 1576.

The last major event for the Mali Empire happened in 1599. Under Mansa Mahmud IV, Mali tried to capture Jenne. Mahmud sought help from other rulers. But his ally secretly joined the Moroccans. The Malian and Moroccan armies fought at Jenne on April 26. The Moroccans won because of their firearms and their ally's betrayal. But Mahmud managed to escape.

The Empire's End

The Mandinka people themselves caused the final fall of the empire. Around 1610, Mahmud Keita IV died. Oral tradition says he had three sons who fought over what was left of Manden. No single Keita ruler controlled Manden after Mahmud Keita IV's death. This led to the end of the Mali Empire.

Manden Splits Apart

The old heartland of the empire split into three areas. Kangaba became the capital of the northern area. The Joma area, ruled from Siguiri, controlled the central region, including Niani. Hamana became the southern area, with its capital at Kouroussa. Each ruler used the title of mansa. But their power only reached their own area. Even with this split, Mandinka people still controlled the region until the mid-17th century. The three states often fought each other. But they usually stopped when outsiders attacked.

The Bamana Attacks

In 1630, the Bamana people of Djenné declared a holy war against all Muslim powers in present-day Mali. They attacked Moroccan rulers in Timbuktu and the mansas of Manden. In 1645, the Bamana attacked Manden. They took control of both sides of the Niger River, all the way to Niani. This campaign severely weakened Manden. It destroyed any hope of the three mansas working together. Only Kangaba was spared from this attack.

Niani is Destroyed

Mama Maghan, the mansa of Kangaba, fought against the Bamana in 1667. He attacked Segou for three years. But Segou successfully defended itself, and Mama Maghan had to retreat. As a counter-attack, or as part of their plan, the Bamana attacked and burned Niani in 1670. Their forces marched north to Kangaba. There, the mansa had to make peace with them. He promised not to attack downstream of Mali. The Bamana also promised not to go further upstream than Niamina. After these terrible events, Mansa Mama Maghan left the capital of Niani.

How Mali Was Governed

Early Structure

When Mari Djata founded the empire, it included the "three freely allied states" of Mali, Mema, and Wagadou. It also had the "Twelve Doors of Mali."

The Twelve Doors of Mali were a group of conquered or allied lands. Most were within Manden. Their leaders promised loyalty to Sundiata and his family. In return, they became "farbas." A farba was like a military governor. These farbas ruled their old kingdoms in the Mansa's name. They kept most of their power.

The Gbara (Great Assembly)

The Gbara, or Great Assembly, was the main council of state for the Mandinka people. It lasted until the empire fell in 1645. Its first meeting set up social and economic rules. These included rules against mistreating prisoners and slaves. It also set clear rules for different clans. Sundiata also divided the land among the people. He made sure everyone had a place in the empire. He also set exchange rates for common goods.

The Gbara acted like the ruler's cabinet. Different officials had different jobs, like war, justice, or foreign relations. All major groups in Manden society were part of it.

Managing the Territory

The Mali Empire covered a huge area for a long time. This was possible because its government was not too centralized. The farther you went from the capital, the less direct power the mansa had. But the mansa still collected taxes and had control over the area. This kept his subjects from revolting. Mali balanced central and local power. It divided the empire into provinces and vassal states. These were ruled in different ways.

Central Control

The Mansa had the final, unquestioned authority. Meetings with the Mansa followed strict rules. Conquered areas were ruled directly by the state. A military governor, called a farin or farba, managed these areas. The farin was chosen by the Mansa. His duties included managing soldiers, collecting taxes, and overseeing justice. He could also take power from local leaders if needed. This system helped new areas become part of the empire.

The job of farba was very important. Their children could inherit it if the mansa approved. The mansa could also replace a farba if they became too powerful.

Local Control

Most of the empire was made up of independent kingdoms or communities. They recognized the Mansa's authority and paid tribute. At the local level (village, town), family heads chose a village leader. County administrators were appointed by the province governor. Only at the province level did the central government really get involved. Provinces chose their own governors. The mansa had to approve these governors and watched over them. If a governor wasn't capable, a farba might be sent to oversee or rule the province directly.

Conquered lands that were peaceful could get this local control. But important trade areas or rebellious lands could lose this privilege. Then, a farin would be put in charge.

Mali's Economy

At its peak, Mali was very rich, especially because of its gold trade.

Trade Routes

Trade was key to Mali's success. Its golden age happened when Timbuktu came under the Mansa's control. The empire taxed every bit of gold, copper, and salt that entered its borders. By the 14th century, there was a "Manding peace" in West Africa. This allowed trade to grow.

There wasn't one standard currency. Several forms were used. Towns in the Sahel and Sahara were important stops for long-distance trade caravans. They traded many West African products. For example, at Taghaza, salt was traded. At Takedda, copper was traded. Ibn Battuta saw slaves being used in both towns. He traveled with slaves who carried goods for trade. On his way back from Takedda, his caravan carried 600 female slaves. This shows that slavery was a big part of the empire's trade.

Gold Riches

Mali's gold wealth came mostly from taxes and trade, not from directly owning gold mines. Gold nuggets belonged only to the mansa. It was illegal to trade them within the empire. All gold nuggets went to the imperial treasury. In return, people got an equal value of gold dust. Gold dust had been used as money since the Ghana Empire. Mali used this practice to control prices. The most common measure for gold was the mithqal (about 4.5 grams of gold). This term was also used for dinar.

By the early 14th century, Mali was the source of almost half the world's gold. This gold came from mines in Bambuk, Boure, and Galam. Gold mines in Boure, in modern-day Guinea, were found around the late 12th century.

Salt: A Valuable Commodity

Salt was another very important trade good. In sub-Saharan Africa, it was as valuable as gold, sometimes even more. It was cut into pieces and used to buy goods. While it was as good as gold in the north, it was even more valuable in the south, where it was rare. Every year, merchants came to Mali with camel loads of salt to sell. Ibn Battuta wrote that in Taghaza, a major salt mine, there were no trees, only sand and salt mines. Only the workers lived there. They ate dates, camel meat, and millet. Buildings were made of salt slabs with camel skin roofs. The salt was dug from the ground and cut into thick slabs. Two slabs were loaded onto each camel. They were taken south to Oualata and sold. The value of salt depended mainly on how much it cost to transport it. One camel load of salt sold for 8–10 mithqals of gold in Walata. But in Mali itself, it was worth 20–30 ducats, sometimes even 40.

Copper Trade

Copper was also a valuable item in Mali. According to Ibn Battuta, copper was mined from Takedda in the north. It was traded in bars in the south for gold. Some sources say 60 copper bars were traded for 100 dinars of gold.

Mali's Military Power

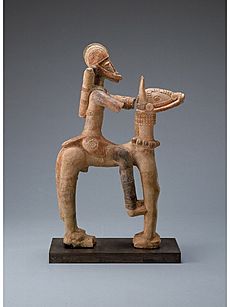

The many conquests in the late 13th and 14th centuries show that Mali had a strong military. Sundiata is credited with organizing the Manding army at first. But it changed a lot over time. Thanks to steady tax money and stable government, Mali could project its power far and wide. It had a well-organized army with skilled horsemen and many foot soldiers. An army was needed to guard the borders and protect its rich trade. Terracotta figures show cavalry, suggesting the empire's wealth, as horses were not native to Africa.

Army Strength

The Mali Empire had a semi-professional, full-time army to defend its borders. The whole nation was involved. Each clan had to provide a certain number of fighting-age men. These men had to be freemen and bring their own weapons. Historians say Mali's standing army reached 100,000 soldiers. Of these, 10,000 were cavalry. With help from river clans, this army could be quickly moved across the empire. Many sources say that war canoes were widely used on West Africa's waterways for transport and fighting. Most canoes were made from a single large tree trunk.

Army Structure

In the 14th century, Mali's army was divided into northern and southern commands. These were led by the Farim-Soura and Sankar-Zouma. Both were part of Mali's elite warriors. They were called the ton-ta-jon-ta-ni-woro ("sixteen carriers of quivers"). Each leader gave advice to the mansa at the Gbara. But only these two had such wide power.

These leaders belonged to an elite group of cavalry commanders called the farari ("brave men"). Each "brave" had infantry officers under them. These officers led free troops into battle. There were also officers for slave troops. The slave troops were called sofa ("guardian of the horse").

Weapons and Gear

The Mali Empire's army used many different weapons. This depended on where the troops came from. Only the sofa (slave troops) were given weapons by the state. They used bows and poisoned arrows. Free warriors from the north used large shields made of reed or animal hide. They also used a stabbing spear called a tamba. Free warriors from the south used bows and poisonous arrows.

The bow was very important in Mandinka warfare. It was a symbol of military power. Archers made up a large part of the army. Three archers supported one spearman in some areas. Mandinka archers used barbed, iron-tipped arrows that were usually poisoned. They also used flaming arrows to attack walled cities. While spears and bows were the main weapons for foot soldiers, swords and lances were used by cavalry. Ibn Battuta described sword fighting displays before the mansa. Another common weapon was the poison javelin, used in small fights. Mali's horsemen also used iron helmets and chain mail armor for defense. They also used shields similar to those of the infantry.

Society and Culture

Architecture of Mali

Malian architecture was known for its Sudano-Sahelian architecture style. This style uses mudbricks and adobe plaster. Large wooden beams stick out from the walls of big buildings like mosques or palaces.

The exact age of the original Great Mosque of Djenné is not certain. It might be as old as 1200 or as new as 1330. The current building was built in 1907. It looks like the original design. The earliest writing about the old Djenne mosque says that a Sultan Kunburu became Muslim. He tore down his palace and built a mosque on the site. Then he built a new palace nearby.

The Sudano-Sahelian style became very popular during Mansa Musa I's rule. He built many projects, including the Great Mosque of Gao and the Royal Palace in Timbuktu. An architect from Mecca helped build the palace.

Mali's Lasting Impact

The Mali Empire had a huge effect on West African societies, even long after it declined. Its growth spread Mande culture and the Mande languages. This spread went from the Gambia River to what is now Burkina Faso. It also spread through Dyula traders to trading centers on the south coast. Across this whole region, political systems with Malian structures and terms lasted until colonial times and beyond.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Imperio de Malí para niños

In Spanish: Imperio de Malí para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |