Mandinka people facts for kids

Mansa Musa's visit to Mecca in 1324 CE with large amounts of gold attracted Middle Eastern Muslims and Europeans to Mali.

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 11 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3,786,101 (29.4%) | |

| 1,772,102 (8.8%) | |

| 900,617 (5.6%) | |

| 700,568 (34.4%) | |

| 647,458 (2%) | |

| 212,269 (14.7%) | |

| 166,849 (3.2%) | |

| 160,080 (2.3%) | |

| Languages | |

Western Maninka, Eastern Maninka, Kita Maninka language, Mandinka |

|

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam (Almost entirely) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Mandé peoples, especially the Bambara, Dioula, Yalunka, and Khassonké | |

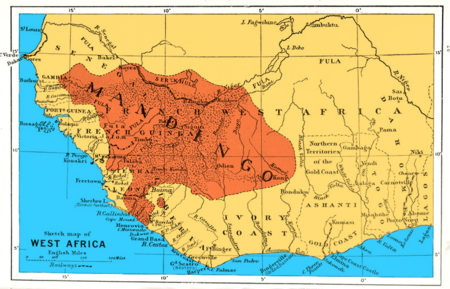

The Mandinka (also called Malinke) are a large ethnic group in West Africa. You can find them mainly in southern Mali, The Gambia, southern Senegal, and eastern Guinea. There are about 11 million Mandinka people. They are the biggest group within the Mandé peoples. They are also one of the largest language groups in all of Africa.

The Mandinka speak Manding languages. These languages are used by many people across West Africa. Most Mandinka people follow the Islamic faith. They are mostly farmers who grow their own food. They live in small villages. Their biggest city is Bamako, which is the capital of Mali.

The Mandinka are the descendants of the Mali Empire. This empire became powerful in the 1200s. It was founded by King Sundiata Keita. His empire grew to cover a huge part of West Africa. The Mandinka moved west from the Niger River. They were looking for better farming land and new places to conquer. Today, Mandinka people live in the West Sudanian savanna region. This area stretches from The Gambia and Casamance in Senegal to Mali, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau.

Even though they are spread out, the Mandinka are the largest ethnic group only in Mali, Guinea, and The Gambia. Most Mandinka live in family groups in traditional villages. Their society has different social levels or castes. Mandinka communities usually govern themselves. They are led by a chief and a group of elders. The Mandinka have a strong oral tradition. This means they pass down stories, history, and knowledge by speaking, not writing. Their music and stories are kept alive by special storytellers called jelis or griots. There are also groups like the donso (hunters) who help preserve traditions.

Between the 1500s and 1800s, many Mandinka people were captured and taken to the Americas. They were forced into slavery. They mixed with people from other groups. This created a new Creole culture. The Mandinka people greatly influenced the African heritage of people in Brazil, the Southern United States, and the Caribbean.

Contents

History of the Mandinka People

Where the Mandinka Came From

The history of the Mandinka, like many Mandé peoples, starts with the Ghana Empire. This empire was also known as Wagadu. Mandé hunters started communities in a place called Manden. This area became important for Mandinka politics and culture. They also settled in Bambuk and the Senegal River valley. Mandé people spread from the Atlantic Ocean all the way to Gao.

The Mandinka and Bambara people believe their first ancestors were Kontron and Sanin. They were the first "hunter brotherhood." Manden was known for having many animals and thick forests. This made it a popular place for hunting. The Camara (or Kamara) family is thought to be the oldest family in Manden. They left Wagadou because of a drought. They founded the first Manding villages: Kiri, Kirina, Siby, and Kita. Many Mandinka families today came from Manden. Manden was the region where the Mali Empire began. This was under the leadership of Sundiata Keita. Before the empire, Manden was made up of many small kingdoms. These kingdoms formed after the Ghana empire fell in the 1000s.

The Powerful Mali Empire

During the time of Sundiata Keita, these small kingdoms joined together. The Mandinka people expanded west from the Niger River basin. This was led by Sundiata's general, Tiramakhan Traore. This expansion was part of creating a large empire. This is told in the oral tradition of the Mandinka people. This movement began in the late 1200s.

Another group of Mandinka, led by Faran Kamara, moved southeast of Mali. A third group expanded with Fakoli Kourouma.

As they moved, many Mandinka gold workers and metal smiths settled. They lived along the coast and in the hilly Fouta Djallon area. Their presence and products attracted Mandinka merchants. This brought trading caravans from North Africa and the eastern Sahel. This also led to conflicts with other groups, like the Wolof people.

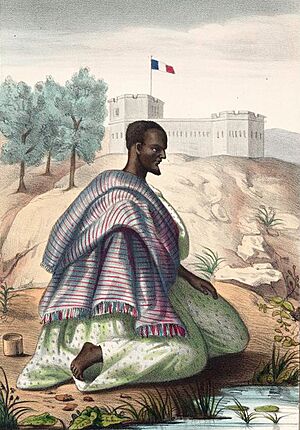

Trade caravans to North Africa and the Middle East brought Islamic people to the Mandinka region. Muslim traders wanted to be part of the Mandinka communities. This likely started efforts to convert the Mandinka to Islam. In Ghana, for example, the Almoravids divided the capital into two parts by 1077. One part was Muslim, the other was not. Muslim influence from North Africa reached the Mandinka region even before this. It came through Islamic trading groups.

In 1324, Mansa Musa, who ruled Mali, went on a Hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca. He traveled with a caravan carrying lots of gold. An Arabic historian, Shihab al-Umari, wrote about his visit. He said Musa built mosques in his kingdom. He also started Islamic prayers and brought back Islamic scholars. Musa was very important in bringing North African and Middle Eastern Muslims to West Africa.

The Mandinka people in Mali converted to Islam early on. But those who moved west did not convert right away. They kept their traditional religious beliefs. One legend among the Mandingo of western Africa says that General Tiramakhan Traore led the migration. This was because people in Mali had converted to Islam, and he did not want to. Another legend says the opposite. It claims Traore himself had converted and married Muhammad's granddaughter. These different stories show that Islam arrived before the 1200s. It had a complex relationship with the Mandinka people.

Over time, many Mandinka converted to Islam. This happened through conflicts, especially with the Fula-led jihads (holy wars). Today, most Mandinka in West Africa are Muslim. However, in some areas, like Guinea Bissau, many Mandinka are not Muslim. In Guinea Bissau, 35% are Muslim, over 20% are Christian, and 15% follow traditional beliefs.

The History of Slavery

Slavery and slave trading existed in Mandinka regions before Europeans arrived. The traveler Ibn Battuta wrote about it in the 1300s. Slaves were part of the Mandinka social system. Several Mandinka words, like Jong or Jongo, mean slaves. In the early 1800s, there were fourteen Mandinka kingdoms along the Gambia River. Slaves were part of society in all these kingdoms.

Selling slaves, along with gold, was a big part of trade across the Sahel. This was trade between West Africa and the Middle East after the 1200s. When Portuguese explorers came to Africa, they started buying slaves. The Portuguese began shipping slaves in the 1400s. These were mainly from the Jolof people, and some Mandinka. Evidence of Mandinka slaves being traded dates back to 1497. At the same time, the slave trade to the Mediterranean and within Africa continued.

Slavery grew a lot between the 1500s and 1800s. The Portuguese saw parts of Guinea and Senegambia as their slave sources. Their documents from the 1500s to 1700s called it "our Guinea." They complained about other European nations taking over the slave trade. Their slave exports from this region almost doubled in the late 1700s. Most of these slaves went to Brazil.

Historians have different ideas about why so many Mandinka people were taken as slaves. Some say there was constant fighting between ethnic groups. Weapons sold by slave traders made this worse. The money from selling slaves also encouraged groups to raid for captives. If one group was attacked, they felt justified in attacking others. Slavery was already common before the 1400s. Most enslaved people were taken by Arab traders to North Africa and western Asia.

As demand for slaves grew, Futa Jallon became a center for this violence. It was led by an Islamic military government. The commander of Mandinka people in Kaabu, Farim, actively hunted for slaves. Kaabu was one of the first places to supply African slaves to European traders.

Some historians say that Mandinka and other groups already had slaves. These slaves inherited their status by birth and could be sold. Islamic armies from Sudan had long practiced slave raids and trade. The Fula jihad from Futa Jallon expanded this practice.

These jihads captured many slaves to sell to Portuguese traders. These traders were at ports controlled by Mandinka people. Groups that felt unsafe stopped working well. They tried to hide for safety. This made their lives harder. Even less powerful groups joined the cycle of slave raids and violence.

Another historian says this wasn't true for all of Senegambia and Guinea. He says many Mandinka were not sent to the Americas until the mid-1700s to 1800s. During these years, slave records show that about 33% of slaves from Senegambia and Guinea-Bissau were Mandinka. He suggests three reasons for Mandinka being captured: small holy wars by Muslims against non-Muslim Mandinka, economic reasons (Islamic leaders wanted goods from the coast), and attacks by the Fula people on the Mandinka's Kaabu.

Wassoulou Empire

Daily Life and Economy

Today, most Mandinka people are farmers. They grow their own food to live. They rely on peanuts, rice, millet, maize, and raising a few animals. During the wet season, men plant peanuts. These are their main crop to sell for money. Men also grow millet. Women traditionally grow rice by hand. This work is very hard and takes a lot of effort. Only about half of the rice they need is grown locally. The rest is bought from other countries.

The oldest man in a family is the head of the household. Marriages are often arranged by families. Their villages are made of small mud houses. These houses have cone-shaped roofs made of thatch or tin. Villages are organized by clan groups. While farming is the main job, men also work as tailors, butchers, taxi drivers, and metalworkers. Some are soldiers, nurses, or work for aid groups.

Religion and Beliefs

Most Mandinka people today follow Islam.

Some Mandinka mix Islam with their traditional African religions. These people believe that spirits can be controlled. This is mainly through the power of a marabout. A marabout is a religious leader who knows special protective prayers. Often, people will ask a marabout for advice before making important decisions. Marabouts have Islamic training. They write verses from the Qur'an on paper. They sew these into leather pouches. These pouches are worn as protective charms.

The Mandinka converted to Islam over many centuries. Some Mandinka in Senegambia started converting as early as the 1600s. Most Mandinka leatherworkers there converted before the 1800s. Mandinka musicians were among the last to convert. Most became Muslim in the early 1900s. Even as Muslims, they have kept some older religious practices. For example, they still have an annual rain ceremony. They also "sacrifice the black bull" to their old gods.

Society and Culture

Most Mandinka live in family groups in traditional villages. Mandinka villages are quite independent. They are led by a council of older, respected people and a chief. The chief is like the first among equals.

Family and Community Structure

In Mandinka society, the lu (extended family) is the basic unit. It is led by a fa (family head). This person manages relationships with other families. A dugu (village) is made up of many lu. The dugu is led by the fa of the most important lu. This leader is helped by the dugu-tigi (village head). This person is the fa of the first family that settled there. A group of dugu-tigi form a kafu (confederation). This is led by a kafu-tigi. The Keita clan first held the kafu-tigi status. This was before Sundiata Keita expanded and created the mansa (king or emperor).

Social Groups

The Mandinka people have traditionally had different social levels, or castes. This is common among many West African groups. Mandinka society has been divided into three main groups. These are the freeborn (foro), slaves (jongo), and artisans/praise singers (nyamolo). The freeborn are mainly farmers. The enslaved group included workers for farmers. It also included leather workers, potters, metal smiths, and griots.

Mandinka Muslim religious leaders and writers are a separate group. They are called Jakhanke. Their Islamic roots go back to about the 1200s.

These Mandinka social groups are passed down through families. Marriages outside one's group were not allowed. This system is similar to other groups in the African Sahel region. These groups are found in Mandinka communities in The Gambia, Mali, Guinea, and other countries.

Growing Up: Rites of Passage

The Mandinka have a special ceremony called kuyangwoo. It marks when children become adults. After this ritual, children used to spend up to a year living in the bush. Now, it's usually three or four weeks.

During this time, they learn about their adult duties and how to behave. The village prepares for the children's return. A celebration marks their return as new adults to their families. Because of these traditions, a woman's loyalty in marriage stays with her parents and family. A man's loyalty stays with his family.

Marriage Customs

Marriages are usually arranged by family members. This is more common in rural areas. The family of the man who wants to marry sends Kola nuts to the older men of the woman's family. If they accept the nuts, the courtship can begin.

Having more than one wife (polygamy) has been practiced by the Mandinka since before Islam. A Mandinka man can legally have up to four wives. He must be able to care for each of them equally. Mandinka people believe a woman's greatest achievement is having children, especially sons. The first wife has authority over any wives who come after her. The husband has full control over his wives. He is responsible for feeding and clothing them. He also helps the wives' parents if needed. Wives are expected to live together peacefully. They share household tasks like cooking and laundry.

Music and Oral Traditions

Mandinka culture is rich in traditions, music, and spiritual practices. The Mandinka keep their long oral history alive. They do this through stories, songs, and proverbs. In rural areas, modern schooling is not very common. Many Mandinka cannot read and write in the Latin alphabet. But more than half of adults can read the local Arabic script (including Mandinka Ajami). Small schools where children learn the Qur'an are very common. Mandinka children are given their name on the eighth day after they are born. Children are almost always named after an important family member.

The Mandinka have a rich oral history. It is passed down through songs by griots. This way of sharing history through music is a special part of Mandinka culture. They are known for their drumming. They are also famous for their unique musical instrument, the kora. The kora is a twenty-one-stringed West African harp. It is made from a dried, hollowed-out gourd covered with cow or goat skin. The strings are made of fishing line (they used to be made from cow tendons). It is played to go along with a griot's singing or by itself.

A Mandinka religious and cultural site is being considered for World Heritage status. It is in Guinea at Gberedou/Hamana.

The Kora Instrument

The kora has become a symbol of traditional Mandinka musicians. The kora has 21 strings. It is made from half a calabash (a type of gourd). This is covered with cow's hide, held on by decorative tacks. The kora has sound holes on the side. These are used to hold coins given to the praise singers. These coins show thanks for their performance. The praise singers are called jalibaas or jalis in Mandinka.

Mandinka in Books and Media

- Malian author Massa Makan Diabaté wrote novels about Mandinka legends. His book Janjon won a big literary prize in 1971. His other novels like The Lieutenant of Kouta try to show the proverbs and customs of the Mandinka people.

- In 1976, American writer Alex Haley wrote Roots: The Saga of an American Family. This book traced his family history. It went back to an ancestor from the 1700s named Kunta Kinte. He was a Mandinka man captured and brought to North America as a slave. Haley traveled to West Africa for his research. He heard about his people from a griot. The book was a bestseller and became a popular TV mini-series. Some historians have questioned if this family link is entirely accurate.

- Martin R. Delany, an important figure in the 1800s, was partly of Mandinka descent. He was an abolitionist, military leader, politician, and doctor in the United States.

- Sinéad O'Connor's 1988 song "Mandinka" was inspired by Alex Haley's book.

- Mr. T, a famous American TV star, once said his unique hairstyle was based on a Mandinka warrior. He saw a picture in National Geographic magazine. He said his gold chains symbolized his ancestors who were brought as slaves.

Notable Mandinka People

Burkina Faso

- Joffrey Bazié, footballer

- Amadou Coulibaly, footballer

- Yaya Darlaine Coulibaly

- Djibril Ouattara

- Joseph Ki-Zerbo, political leader and historian

- Bakary Koné, footballer

- Cheick Kongo, mixed martial artist

- General Sangoulé Lamizana, former President (1966–1980)

- Oumarou Nébié

- Gustavo Sangaré

- Colonel Saye Zerbo, former President (1980–1982)

The Gambia

- Adama Barrow, current president of The Gambia

- Modou Barrow

- Musa Barrow

- Assan Ceesay

- Jatto Ceesay, footballer

- Ousainou Darboe, Foreign Minister

- Sheriff Mustapha Dibba, politician and First Vice President

- Alieu Fadera

- Abdoulie Janneh, former UN Under-Secretary General

- Sidia Jatta, opposition politician

- Alhajj Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara, first President of The Gambia

- Sona Jobarteh, first female kora artist

- Modou Jobe

- Jaliba Kuyateh, kora artist and musician

- Alasana Manneh

- Kekuta Manneh

- Yankuba Minteh

- Professor Lamin O. Sanneh, academic and author

- Abdoulie Sanyang

- Amadou Sanyang

- Ebrima Sohna

- Alagie Sosseh

- Foday Musa Suso, international musician

- Mohamadou Sumareh

- Momodou Touray

- Saikou Touray

Guinea

- Sekouba Bambino, musician

- Abdoul Camara

- Moussa Camara

- Ibrahima Cissé

- Momo Cissé

- Seydouba Cissé

- Alpha Condé, former President

- Cheick Condé

- Mamady Condé, former Foreign Minister

- Sékou Condé, footballer

- Sona Tata Condé, musician

- Amadou Diawara

- Djeli Moussa Diawara, musician (also known as Jali Musa Jawara)

- Kaba Diawara, footballer

- Mamady Doumbouya, military officer

- Daouda Jabi, footballer

- Mamadi Kaba, footballer

- Sory Kaba, footballer

- Mamadou Kane

- Mory Kanté, kora musician

- Alhassane Keita, footballer

- Mamady Keïta, musician

- Naby Keita, footballer

- Kabiné Komara, former Prime Minister

- Famoudou Konaté, musician

- Mory Konaté

- General Sékouba Konaté, former Head of State

- Lansana Kouyaté, former Prime Minister

- N'Faly Kouyate, musician

- Fodé Mansaré, footballer

- Petit Sory, footballer

- Morlaye Sylla

- Sekou Touré, President (1958–1984); grandson of Samory Touré

- Diarra Traoré, former Prime Minister

- Samori Ture, founder of the Wassoulou Empire

- Mohamed Yattara

Guinea Bissau

- Aladje

- Yalany Baio, footballer

- Mamadi Camará

- Romário Baró

- Mimito Biai, footballer

- Sana Canté, activist

- Rui Dabó, footballer

- Tomás Dabó, footballer

- João Jaquité, footballer

- Jorginho

- Madi Queta, footballer

- Neemias Queta, basketball player

- Alfa Semedo

- Panutche Camará, footballer

Ivory Coast

- Sidiki Bakaba, actor and filmmaker

- Alpha Blondy, reggae musician

- Ibrahim Cissé, footballer

- Sekou Cissé, footballer

- Fousseny Coulibaly, footballer

- Kafoumba Coulibaly, footballer

- Souleymane Coulibaly

- Siriki Dembélé, footballer

- Henriette Diabaté, former politician

- Oumar Diakité

- Ismaël Diomandé

- Sinaly Diomande, footballer

- Cheick Doukouré

- Emmanuel Eboué, footballer

- Tiken Jah Fakoly, reggae musician

- Moryké Fofana

- Hassane Kamara, footballer

- Abdul Kader Keïta, footballer

- Fadel Keïta

- Karim Konaté, footballer

- Arouna Koné, footballer

- Bakari Koné, footballer

- Moussa Koné

- Tiassé Koné, footballer

- Ahmadou Kourouma, writer

- Alassane Ouattara, current President; former Prime Minister

- Badra Ali Sangaré

- Ibrahim Sangaré

- Alpha Sissoko

- Guillaume Soro, politician

- Kolo Touré, footballer

- Sékou Touré, politician, environmental engineer

- Yaya Touré, footballer

- Abdou Razack Traoré

- Adama Traoré

- Hamed Traorè

- Lacina Traoré

- Marco Zoro, footballer

Liberia

- Prince Balde

- Momolu Dukuly, former Foreign Minister

- Abu Kamara

- Mohammed Kamara

- Nohan Kenneh

- Amara Mohamed Konneh, Minister of Finance

- G. V. Kromah, former Council of State member

- Alex Nimely

- Sylvanus Nimely

- Mohammed Sangare

- Ansu Toure

Mali

- Zoumana Camara

- Soumaila Coulibaly, footballer

- Bako Dagnon, griot singer

- Souleymane Dembélé

- Cheick Diabaté, footballer

- Massa Makan Diabaté, historian, writer

- Mamadou Diabate, musician

- Toumani Diabaté, musician

- Drissa Diakité

- Yoro Diakité, former Prime Minister

- Aboubacar Diarra

- Mahamadou Diarra

- Fatoumata Diawara, musician

- Fousseni Diawara, footballer

- Daba Diawara, politician

- Moussa Djenepo

- Diaranké Fofana

- Youssouf Fofana

- Aoua Kéita, politician and activist

- Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, President (2013–2020)

- Habib Keïta

- Modibo Keïta, President (1960–1968)

- Salif Keita, musician

- Seydou Keita, footballer

- Sundiata Keita, founder of the Mali Empire

- Tiécoro Keita

- Amy Koita, musician

- Ibrahima Konaté

- Pa Konate

- Sidy Koné

- Makan Konaté

- Moussa Kouyate, musician

- Mansa Musa, famous Emperor of the Mali Empire

- Hadi Sacko

- Oumou Sangaré, musician

- Djibril Sidibé, footballer

- Mamady Sidibé, footballer

- Modibo Sidibé, Prime Minister (2007–2011)

- Baba Sissoko, musician

- Mohamed Sissoko, footballer

- Adama Soumaoro

- Almamy Touré

- Amadou Toumani Touré, President (2002–2012)

- Birama Touré

- Adama Traoré

- Djimi Traoré

- Dramane Traoré

- Kalilou Traoré

- Mahamane Traoré

- Sidiki Diabaté

Senegal

- Brancou Badio

- Ibrahima Baldé

- Keita Baldé, footballer

- Dawda Camara

- Lamine Camara

- Papa Demba Camara, footballer

- Souleymane Camara

- Pathé Ciss

- Aliou Cissé, former footballer

- Pape Abou Cissé

- Papiss Cissé, footballer

- Aly Cissokho

- Issa Cissokho

- Abdou Diakhaté

- Pape Diakhaté

- Lamine Diatta

- Krépin Diatta, footballer

- Souleymane Diawara, footballer

- Baba Diawara

- Boukary Dramé, footballer

- Lamine Gassama, footballer

- Sidiki Kaba, Justice Minister

- General Balla Keita, MiNUSCA Force Commander

- Seckou Keita, musician

- Kalidou Koulibaly

- Moussa Konaté, footballer

- Cheikhou Kouyaté, footballer

- Moustapha Mbow

- Opa Nguette, footballer

- Amadou Onana

- Abdoulaye Sané

- Lamine Sané, footballer

- Boubakary Soumaré

- Tony Sylva

- Amara Traoré, former footballer

- Aminata Touré, former Prime Minister

- Zargo Touré, footballer

Sierra Leone

- Amadou Bakayoko

- Ibrahim Jaffa Condeh, journalist

- Kanji Daramy, journalist and spokesman

- Mabinty Daramy, Deputy Minister of Trade and Industry

- Mohamed B. Daramy, former minister

- Kemoh Fadika, High Commissioner

- Lansana Fadika, businessman

- Saidu Fofanah

- Bomba Jawara, former MP

- Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, President (1996–2007)

- Haja Afsatu Kabba, former Minister

- Karamoh Kabba, author and journalist

- Mohamed Kakay, former MP

- Alhaji Kamara

- Glen Kamara

- Mohamed Kamara

- Musa Noah Kamara

- Saidu Bah Kamara

- Kadijatu Kebbay, model

- Brima Dawson Kuyateh, journalist

- Sidique Mansaray, footballer

- Tejan Amadu Mansaray, former MP

- Shekuba Saccoh, former ambassador and minister

- K-Man (born Mohamed Saccoh), musician

- Alhaji A. B. Sheriff, former MP

- Sheka Tarawalie, journalist and former minister

- Mohamed Buya Turay

- Sitta Umaru Turay, journalist

Togo

- Mohamed Kader Toure

- Assimiou Touré

United States

- Aboubacar Keita

- Mo Bamba, basketball player

- Martin Delany, abolitionist, journalist, physician, and writer

- Alex Haley, writer, author of Roots: The Saga of an American Family

- Kunta Kinte, documented Mandinka warrior, ancestor of Alex Haley and character in Roots

- Gabourey Sidibe, actress

- Foday Musa Suso, griot musician and composer

- Sheck Wes, rapper and basketball player

See also

- Djembe

- Gravikord

- Mande languages

- Mandingo people of Sierra Leone

- Mane people

- N'Ko alphabet