Mandé peoples facts for kids

The Mandé peoples are a large group of people in West Africa who speak similar languages, called Mande languages. You can find different Mandé-speaking groups all over West Africa, from the rainy rainforests near the coast to the dry Sahel region. Their languages are split into two main groups: East Mandé and West Mandé.

One of the most famous Mandé groups is the Mandinka (also known as Malinke). They are known for starting one of the biggest empires in West Africa's history. Other large Mandé-speaking groups include the Soninke and Susu. Smaller groups like the Ligbi, Vai, and Bissa are also part of the Mandé family. These groups have many different cultures, foods, and beliefs, but they are all connected by their language.

Long ago, after moving from the central Sahara desert, Mandé-speaking people created the Tichitt culture in what is now Mauritania. This was a very early civilization in West Africa. Later, they spread out and helped establish important cities and empires like Méma, Macina, Dia Shoma, Jenne Jeno, and the famous Ghana Empire.

Today, most Mandé-speaking people are Muslim. Their religion, Islam, has been very important to their identity, especially for those living in the Sahel. The Mandé people were skilled traders, using the Niger River and overland routes. They also built strong armies, which helped expand empires like the Ghana Empire, Mali Empire, Kaabu, and Wassoulou states. Their culture and ideas also influenced many other groups in West Africa, like the Fula and Songhai.

Contents

History of the Mandé Peoples

Early Beginnings in the Sahara

Long, long ago, after a period of hunter-gatherers, the Pastoral Period began in the Central Sahara. As the Sahara became drier, hunter-gatherers and cattle herders likely moved along seasonal rivers towards the Niger River and Chad Basin in West Africa. Around 4000 BCE, herders in the Sahara started to develop complex social structures, like trading cattle as valuable goods. This early organization helped set the stage for more advanced societies, such as those found at Dhar Tichitt.

The Tichitt Culture

After leaving the Central Sahara, early Mandé-speaking people settled in the Tichitt region of the Western Sahara. The Tichitt Tradition in southeastern Mauritania lasted from about 2200 BCE to 200 BCE. This culture was quite advanced. It had a four-level social structure, where people farmed cereals like pearl millet. They also worked with metals and built many tombs. Rock art was also a part of their culture.

The Tichitt Tradition might have been the first large, complex society in West Africa. It helped lead to the creation of states in the region. Farming was important, with millet being grown as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. Later, around 1000 BCE, people in the Tichitt culture also started working with iron. They even used pearl millet to help make their iron furnaces work better. They also used copper at some sites.

After its decline in Mauritania, the Tichitt Tradition spread to the Middle Niger region of Mali. Here, it continued to develop, leading to the rise of the Ghana Empire around 1 CE.

Djenné-Djenno: An Ancient City

The ancient city of Djenné-Djenno was located in the Niger River valley in Mali. It is one of the oldest urban centers in Sub-Saharan Africa. This city, about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) from modern Djenné, was important for long-distance trade. People there might have even started growing African rice.

Djenné-Djenno was likely founded by the ancestors of the Bozo people, who are also Mandé-speaking. The city existed from the 3rd century BCE to the 13th century CE. It is believed the city was later abandoned, and its people moved to the current location of Djenné, possibly due to the spread of Islam and the building of the Great Mosque of Djenné.

The Ghana Empire

Around 1500 BCE, different clans of the early Soninke, one of the oldest Mandé-speaking groups, united under a leader named Dinga Cisse. This group formed a powerful confederation of states. The Ghana Empire was perfectly located between the desert, which provided salt, and the gold fields to the south. This made it a great place for trade. They traded with areas to the north, reaching Morocco.

Ghanaian society had large farming and cattle-raising communities. Its merchants were very successful, controlling trade routes across the Sahara. They traded goods like leather, ivory, salt, gold, and copper for finished products. By the 10th century, the Ghana Empire was incredibly rich and powerful, controlling a huge area that stretched across parts of modern-day Senegal, Mali, and Mauritania. An Arab traveler in 950 AD described the Ghanaian ruler as the "richest king in the world" because of his gold.

In the 11th century, the empire started to decline. The king lost his control over trade, a severe drought hurt farming and cattle, and different clans began to fight. Some historical accounts say that Almoravid Muslims from the North invaded Ghana.

Before the Almoravids, Islam had slowly spread without military takeovers. After the Almoravids left, new gold fields were found further south, and new trade routes opened to the east. Just as Ghana seemed like it might recover, it was attacked by the Susu people, another Mandé-speaking group, led by Sumanguru. From this conflict, a new powerful leader, Sundiata Kéita, emerged in 1235. By the mid-13th century, the great Ghana Empire had completely fallen apart and was soon replaced by Sundiata's Mali Empire.

The Mali Empire

The most famous emperor of Mali was Mansa Musa (1307–1332), Sundiata's grandson. He was also known as “Kan Kan Mussa" or "The Lion of Mali." His journey to Mecca in 1324 made Mali famous on European maps. He traveled with an enormous group, including 60,000 porters, each carrying 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds) of pure gold. He had so much gold that when he stopped in Egypt, the value of the Egyptian currency actually dropped! Because of Mansa Musa's wealth, the names of Mali and Timbuktu appeared on world maps in the 14th century.

In the 12th century CE, the University of Sankore in Timbuktu became a major center for learning. It started as the Mosque of Sankore. Along with the Mosque of Sidi Yahya and the Mosque of Djinguereber, it formed what is known as the University of Timbuktu, a very important place for education in ancient times.

After several generations, the Mali Empire was eventually taken over by the Songhai empire, led by Askia Muhammad I.

Later Mandé History

After the fall of the great empires of the northern Mandé-speaking people (like the Mandinka and Soninke), other Mandé-speaking groups became more prominent. These included the Mane, who were Southern Mandé speakers (like the Mende and Kpelle). They moved from the east into the western coast of Africa in the early 1500s. Their clothing, weapons, language, and traditions showed where they came from. The Mane moved along the coast of modern Liberia, fighting and usually winning against the groups they met. They only slowed down when they met the Susu, another Mandé people, in what is now northwestern Sierra Leone, who had similar fighting skills.

Rock art made by Manding peoples is mostly found in Mali, where the Malinke and Bambara live. This art, using black, white, or red paint, often shows geometric shapes, animals (like lizards), and humans.

When the French colonized West Africa, it greatly changed the lives of Mandé-speaking people. Many soldiers died in wars with the French. The Mandé also became more involved in the Atlantic slave trade for money. Later, the colonial borders drawn by European powers divided their populations. Today, Mandé-speaking people are still active in West African politics, with many individuals from these groups becoming presidents in various countries.

Since the 1900s, conflicts between Mandé-speaking peoples and other African groups have increased. This is partly because of desertification, which has forced them to move south to find work and resources. This competition has sometimes led to fighting with other local populations along the coast.

Mandé Culture

Mandé-speaking groups usually have a patrilineal kinship system, meaning family lines are traced through the father. They also have a patriarchal society, where men hold most of the power. Many Mandé tribes, like the Mandinka and Soninke, practice Islam, often mixed with some of their traditional beliefs. They usually perform ritual washing and daily prayers. Mandinka women often wear veils. The Mandinka also have a special social custom called sanankuya, or "joking relationship," between different clans.

Secret Societies

Among the Mende, Kpelle, Gbandi, and Loma Mandé-speaking groups in Sierra Leone and Liberia, there are secret groups for men and women. These are known as Poro (for men) and Sande or Bundu (for women). These societies are based on old traditions, possibly from around 1000 CE. They help manage the rules of their society and guide boys and girls through important rites of passage as they grow into adults.

Social Structure

Some Mandé-speaking groups, like the Mandinka, Soninke, and Susu, traditionally had a social system with different levels, sometimes called a "caste" system. This system included nobility and vassals. There were also serfs, who were often prisoners or captives from wars. The families of former kings and generals had a higher status than others.

Many Mandé cultures also traditionally have groups of skilled craftspeople, such as blacksmiths, leatherworkers, potters, and woodcarvers. There are also bards, known as griots. These craft and bardic groups are called "nyamakala" by Manding peoples and "Nyaxamalo" by the Soninke people.

Over time, these social differences have become less strict, especially as economic situations changed. While the Mandé first arrived in many places as raiders or traders, they gradually adapted. Today, most Mandé people work as farmers or nomadic fishermen. Some are skilled blacksmiths, cattle herders, or griots.

Fadenya: A Mandé Concept

Fadenya, or “father-childness,” is a word used by the Manding people (like the Mandinka). It originally described the tensions between half-brothers who shared the same father but had different mothers. This idea of fadenya has grown and is now often used to describe the lively political and social energy of the Mandé world. It is often compared to badenya, or mother-childness.

Oral Traditions

Among the Mandinka, Soninke, and Susu Mandé-speaking groups, history is passed down through spoken stories. A very famous example is the Epic of Sundiata of the Mandinka people. Among the Mandinka, there are special teaching centers called kumayoro. Here, keepers of tradition, known as nyamankala, teach oral histories and techniques. These nyamankala are very important because they preserve the Mandinka culture's oral traditions. The Kela school is especially known for this work, which is why different versions of the Sundiata epic are quite similar. The Kela version is considered the official one and is performed every seven years. This version even includes a written document called a tariku, which is a unique mix of written and oral history in Mandinka culture.

The epic is usually performed in two ways: one for teaching or practice, and a more official version for a large audience. The teaching performance might involve gifts from clans mentioned in the epic. The official version can use musical instruments and does not allow audience interruptions. Different Mandé clans use different instruments when they perform the epic.

Literature

Mandé literature includes the Epic of Sundiata, a long poem about the rise of Sundiata Keita, who founded the Mali Empire. These stories exist in many forms, from early Arabic accounts to modern recordings. Tarikh al-Fattash and Tarikh al-Sudan are two important historical books from Timbuktu. By the late 1990s, there were reportedly 64 published versions of the Epic of Sundiata. Among Mandé-speaking groups, griots are special storytellers, bards, and historians who pass down these traditions.

Religion

Many Mandé-speaking groups in western West Africa have been mostly Muslim since the 13th century. Others, like the Bambara, became Muslim later, in the 19th century, with some still keeping their traditional beliefs. Muslim Mandinka people also hold traditional beliefs, such as in initiation rituals like Chiwara and Dwo, and beliefs in the power of nyama (a spiritual power in nature). Many smaller Mandé-speaking groups, like the Bobo, still follow their pre-Islamic belief systems completely. Many Mandé groups in Sierra Leone and Liberia were also not fully Islamized.

According to oral histories, Mandé-speaking people, especially the Soninke group, helped spread Islam to non-Mandé groups in the Sahel region through trade and settlement.

Arts

Much of Mandé art is in the form of jewelry and carvings. The masks used in the secret societies of the Marka and the Mendé are very well-known and beautifully made. The Mandé also create lovely woven fabrics that are popular across West Africa. They make gold and silver necklaces, bracelets, armlets, and earrings. The Bambara people and related groups also traditionally create wooden sculptures. Sculptures in wood, metal, and clay have been found, linked to ancient peoples related to the Soninke in Mali.

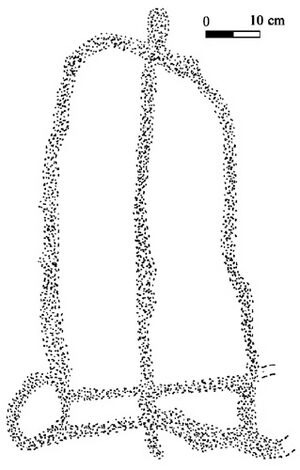

The bells on necklaces are believed to be heard by spirits, ringing in both the world of ancestors and the living. Mandé hunters often wear a single bell, which they can silence when they need to be quiet. Women, however, often wear many bells, which represent community because the bells ring together in harmony.

Djenné-Djenno, an ancient city on the Niger River, is famous for its clay figurines of humans and animals like snakes and horses. Some of these date back to the first and early second millennium AD. These statues likely had a ritual purpose, possibly representing household or ancestral spirits, as ancestor worship was common in the area until the 20th century.

Music

The most famous type of traditional music among Mandé-speaking people is played on the kora. This is a stringed instrument with 21 or more strings, mostly linked to the Mandinka people. It is played by families of musicians known as Jeliw (or Jeli for one person), or in French as griots. The kora is a unique harp-lute with a special wooden bridge. It is considered one of the most complex stringed instruments in Africa.

The N'goni is another instrument played by jelis and is actually the ancestor of the modern banjo.

Griots are professional bards in northern West Africa. They are the keepers of their great oral traditions and history. They are also trusted advisors to Mandinka leaders. Some of the most famous griots today include Toumani Diabate, Mamadou Diabate, and Kandia Kouyaté.

See also

- Griot

- Djembe

- N'goni

- Kora (instrument)

- List of Mandé peoples of Africa

- Mande Studies Association

- Mande languages

- Tichitt Culture

- Ghana Empire

- Djenne-Djenno

- Mali Empire

- Sosso Empire

- Bambara Kingdom

- Kaabu Empire

- Wassoulou Empire

- Kong Empire

- Borgu Emirate

- Gwiriko

- Manneh Warriors

- Nyamakala

- Fadenya

- Sofa Soldiers

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |