Pastoral period facts for kids

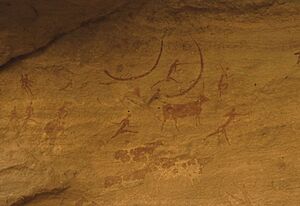

Pastoral rock art is a very common type of ancient art found in the central Sahara Desert. It includes both paintings and engravings on rocks. This art shows people who raised animals (called pastoralists) and hunters using bows. It also shows scenes of people taking care of animals like cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs. This art was made over a long time, from about 6300 BCE to 700 BCE.

The time when Pastoral rock art was made is called the Pastoral Period. It came after the Round Head Period and before the Caballine Period.

The Early Pastoral Period was from 6300 BCE to 5400 BCE. During this time, people brought tamed cattle to the Central Sahara, like the Tadrart Acacus area. Having cattle helped people become more important in their communities. It also allowed them to have extra food and become richer. Because of this, some hunter-gatherers in the Central Sahara started to raise cattle. In return, these hunter-gatherers shared their knowledge about local plants (like Cenchrus and Digitaria) with the new cattle-raising people.

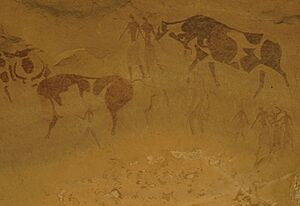

The Middle Pastoral Period (5200 BCE – 3800 BCE) is when most of the Pastoral rock art was created. In the Messak region of Libya, people found cattle bones near engraved rock art of cattle. This suggests that people performed cattle sacrifices there. Stone monuments are also often found near these rock art sites. During this time, people in the Acacus and Messak regions fully developed a cattle-raising economy, including dairying (making milk products). Middle Pastoral people lived in settlements that they used at different times of the year, depending on the monsoon rains.

During the Late Pastoral Period, rock art in the Central Sahara showed fewer animals that live in modern savannas. Instead, it showed more animals that can live in dry places, like those found in the modern Sahel region. At the Takarkori rockshelter, between 5000 BP and 4200 BP, Late Pastoral people herded goats, especially in winter. They also started building large stone monuments (megaliths). These were used as burial sites where people were buried under stone mounds (tumuli). These burial sites were usually away from where people lived.

The Final Pastoral Period (1500 BCE – 700 BCE) was a time of change. People started to move less and settle down more. Final Pastoral people were scattered groups who moved their animals seasonally (this is called transhumance). They built different kinds of burial mounds. Some were separate, while smaller ones were built close together. These people kept small animals like goats and used more plants for food. At Takarkori rockshelter, Final Pastoral people created burial sites for hundreds of individuals around 3000 BP. These sites contained special items from far away and had unique drum-shaped buildings. This period led to the rise of the Garamantian civilization.

Contents

What is Pastoral Rock Art?

Rock art is sorted into different groups. These groups include Bubaline, Kel Essuf, Round Heads, Pastoral, Caballine, and Cameline. They are grouped based on how the art was made, what animals or people are shown, the designs used, and if one drawing is on top of another.

Pastoral rock art is special because it shows tamed cattle. This is different from the painted Round Head rock art. These unique drawings in the Central Sahara suggest that different groups of people came into the area. Over time, later rock art (like Pastoral, Camelline, and Cabelline) showed fewer large wild animals. Instead, they showed more one-humped camels and horses. This change in art shows that the Green Sahara was becoming drier.

How Old is Pastoral Rock Art?

Scientists have different ideas about how to date Central Saharan rock art. Some use a "short chronology" and others a "long chronology." The short chronology suggests that the art developed quickly around 6500 BP. While there is some archaeological proof for this, there isn't enough to explain all the complex cultural changes in the Central Sahara, like different art styles and pottery traditions.

Both the short and long chronologies often rely on circular reasoning. However, an ideal timeline would explain the complex history of the Holocene period and the Sahara, including its cultures and people.

Most people assume that Pastoral rock art is linked to Pastoral Neolithic cultures, but this isn't always proven. The traditional idea is that Pastoral rock art ended, then Horse art began and ended, and then Camel art began and ended. However, it's probably more complex, with different art styles mixing and overlapping. Some pastoralists might not have even created Pastoral rock art. Still, most experts agree that the start of the Pastoral rock art tradition matches the archaeological cultures of the Early Pastoral peoples.

It's hard to tell the age of rock art, especially engravings, by looking at the patina (a thin layer that forms on rocks). This is because the patina can look different depending on how much wind and sand hit the rock. For Pastoral rock art, it's more reliable to think that the painted cattle, engraved cattle (which are more than half of all engraved art), and pastoral designs were made by the same group of people. More research is needed to include rock art that shows wild animals into the current timeline.

Recently, scientists found that dark patina, rich in manganese, is linked to the Green Sahara period. This means engravings with this patina were made before or during the Early Pastoral Period. Gray, light-colored patina, also rich in manganese, is linked to the Sahara becoming drier. Engravings with this patina were made during the Middle Pastoral Period. Red patina, rich in iron, is linked to a dry Sahara. Engravings with this patina were made after the Late Pastoral Period and Final Pastoral Period. If there's no patina, it means the Sahara was completely dry, and the art is very new, from the Garamantian period or later.

We can also tell the age of engraved rock art by looking at when domesticated animals first appeared in the Central Sahara. There's limited proof of domesticated cattle in the Early Pastoral Period (early 6th millennium BCE). This proof increases for the Middle Pastoral Period (5th millennium BCE), showing an established cattle economy. But it decreases by the Garamantian period.

At Wadi al-Ajal, 53% of engraved animal rock art has a manganese-rich patina underneath. This suggests that these animal engravings (like elephants, hartebeest, rhinos) were made during or even before the Early and Middle Pastoral Periods. Many engraved Pastoral rock art pieces of animals might show that pastoralists were more active during these periods, using more natural resources.

During the Middle Pastoral Period, people might have practiced dairy farming and grazed cattle in the Wadi al-Ajal area. They might also have moved their animals seasonally between the southern Messak region and Wadi al-Ajal.

During the Late Pastoral Period and Final Pastoral Period (3800 BCE – 1000 BCE), red-colored patina developed on 33% of the engraved animal rock art at Wadi al-Ajal. This art included animals that can live in the desert, like Barbary sheep and ostriches. As the desert grew (Desertification), new areas became available for creating Pastoral rock art that weren't available before.

Climate Changes in the Sahara

Early Pastoral Period Climate

From about 8000 BP to 7500 BP, the Central Sahara might have been very dry. But from 6900 BP to 6400 BP, the highlands and lowlands of the Central Sahara might have been wet. Because of this, lakes in Edeyen of Murzug and Uan Kasa grew to their largest between 6600 BP and 6500 BP.

Middle Pastoral Period Climate

The environment in the Central Sahara was good during the Early and Middle Pastoral Periods. There was a dry period between these two periods, which lasted from 7300 cal BP to 6900 cal BP.

Late Pastoral Period Climate

The environment might have been quite dry, with wind causing erosion in rockshelters. After 5000 BP, rockshelters might have started to break down as the Sahara became very dry. The plant life changed to look more like a steppe or desert, with plants like Chenopodiaceae and Compositae.

Final Pastoral Period Climate

The environment became even drier, and oases (wet areas in the desert) started to form.

Who Were the Pastoralists?

Pastoral Rock Art and People

Some scientists believe that around 10,000 BP, black African hunter-gatherers moved north from Sub-Saharan western Africa into the Central Sahara, following the monsoon rains. This happened especially in the Acacus region of Uan Muhuggiag. Later, around 7000 BP, pastoralists from the Near East (like Palestine and Mesopotamia) and Eastern Sahara are thought to have moved into the Central Sahara with their animals.

Some rock art from the Acacus region in Libya shows people with features that look like white people. Because of this, some researchers thought the Central Saharan pastoral culture, which created the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag, was a mixed-race group.

Pastoral rock art is thought to show both Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan African peoples. Most art is believed to show mainly Mediterranean people, with fewer Sub-Saharan African people by 4000 BP. However, other experts disagree. They say this idea might be based on modern racial theories that wrongly emphasize outside influences on Africa. They argue that all African body types are shown in the rock art.

Round Head rock art shows human figures with extra details like body designs or masks, and wild animals. The last period of Round Head art shows features that some have called "Negroid" (like strong jaws, big lips, rounded noses). Pastoral rock art is different. It shows scenes from pastoral life and tamed cattle. Its figures have been described as "Europoid" (like thin lips, pointed noses).

Some Pastoral period rock art seems to show Africans with "Caucasian" features living among other African groups. It also seems to show some women with yellow hair. However, it's hard to be sure if these rock art images truly show the different physical features of the African groups who lived in ancient Libya. So, people are careful about making strong conclusions based on these images.

Early Pastoralists

The first pastoralists, who brought tamed sheep, goats, and cattle to the Central Sahara during the Pastoral Period (8000 BP – 7000 BP), have been called Proto-Berbers.

At Gobero, in Niger, hunter-gatherers lived there in the early Holocene period, but left by 8500 BP. After a thousand years, pastoralists started living there around 7500 BP. These groups were different in how they looked (tall and strong versus smaller) and their culture (hunter-gatherer versus pastoralist). This change is similar to what happened in the Acacus region of Libya and the Tassili region of Algeria.

After living together in the Central Sahara, some of the hunter-gatherers who made the Round Head rock art might have mixed with and adopted the culture of the incoming cattle pastoralists by 4000 BP.

At the Uan Muhuggiag rockshelter in the Acacus region, a child mummy (5405 ± 180 BP) and an adult (7823 ± 95 BP) were found. In the Tassili n'Ajjer region, at Tin Hanakaten rockshelter, a child (7900 ± 120 BP) and three adults (9420 ± 200 BP) were found. Studies of the Uan Muhuggiag child mummy and the Tin Hanakaten child showed that these Central Saharan people from earlier periods had dark skin. A researcher named Soukopova (2013) concluded that the skeletons showed two types of people: one with some Mediterranean features, and another with strong "Negroid" features. This means that different-looking Black people lived in the Tassili and likely the whole Central Sahara as early as 10,000 BP.

Some Neolithic farmers from Northeast Africa and the Near East might have been the source for a gene that helps people digest milk (lactase persistence). This gene is found in the Sub-Saharan West African Fulani, the North African Tuareg, and early European farmers. While Fulani and Tuareg herders share this gene, the Fulani version has been around longer. The Fulani milk-digesting gene might have spread with cattle pastoralism between 9686 BP and 7534 BP, possibly around 8500 BP. This fits with evidence of herders milking animals in the Central Sahara by at least 7500 BP.

Where Did Pastoral Animals Come From?

Cattle Origins

Cattle from the Near East

It's thought that tamed cattle were brought to the Tadrart Acacus region rather than being tamed there. Cattle are believed to have been brought into Africa by cattle pastoralists, not to have entered Africa on their own. By the end of 8000 BP, tamed cattle are thought to have arrived in the Central Sahara. The Central Sahara was an important area for spreading tamed animals from the Eastern Sahara to the Western Sahara.

Based on cattle remains found near the Nile (9000 BP) and at Nabta Playa and Bir Kiseiba (7750 BP), tamed cattle might have appeared earlier near the Nile and then spread west into the Sahara. Even though wild aurochs (ancient wild cattle) lived in Northeast Africa, they are thought to have been tamed separately in India and the Near East. After being tamed in the Near East, cattle pastoralists might have moved with them through the Nile Valley and, by 8000 BP, through Wadi Howar into the Central Sahara.

Genetic differences between wild Indian, European, and African cattle (Bos primigenius) around 25,000 BP suggest that cattle might have been tamed in Northeast Africa, specifically the eastern Sahara, between 10,000 BP and 8000 BP. Cattle remains (Bos) might be as old as 9000 BP in Bir Kiseiba and Nabta Playa. While these genetic differences could support the idea of cattle being tamed independently in Africa, it's also possible that wild African cattle mixed with Eurasian cattle.

African Cattle Tamed in Africa

The exact time and place where cattle were tamed in Africa is still being figured out.

A discovery at Affad is very important for understanding the history of cattle in Africa. A large skull piece and a horn from an auroch, the wild ancestor of tamed cattle, were found at sites dating back 50,000 years. These are the oldest auroch remains in Sudan and show the southernmost reach of this species. Based on cattle remains found at Affad and Letti, it's worth rethinking the idea that tamed cattle in Africa came only from the Fertile Crescent.

Indian humped cattle (Bos indicus) and North African/Middle Eastern taurine cattle (Bos taurus) are often thought to have mixed to create Sanga cattle. However, it's more likely that this mixing happened only in the last few hundred years. Sanga cattle are now thought to have come from African cattle within Africa. One idea is that tamed taurine cattle were brought to North Africa and mixed with tamed African cattle, creating Sanga cattle. Or, more likely, tamed African cattle originated in Africa and then developed into different types across regions.

Managing Barbary sheep might be similar to how cattle were tamed in the early Holocene. In the Western Desert, near Nabta Playa, between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago, semi-settled African hunter-gatherers might have independently domesticated African cattle. They did this as a reliable food source and to adapt to a dry period in the Green Sahara, which limited edible plants. Fossils of African Bos primigenius from this time have been found at Bir Kiseiba and Nabta Playa.

At the E-75-6 archaeological site in the Western Desert, between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago, African pastoralists might have managed North African cattle (Bos primigenius) and regularly used a watering hole. In northern Sudan, at El Barga, cattle fossils found in a human burial suggest cattle were in the area.

While it's possible that cattle from the Near East moved into Africa, a larger number of African cattle in the same area share a specific genetic marker (T1 mitochondrial haplogroup) than in other areas. This supports the idea that Africans independently tamed African cattle. Genetic evidence also shows that African cattle separated early from European cattle. The diversity of African cattle's genetic markers does not support the idea that they came from a small group (a bottleneck) from the Near East. All this genetic evidence strongly supports the idea that Africans independently tamed African cattle.

Goat Origins

Sheep and goats spread into the Central Sahara from the Near East between 6500 BP and 5000 BP.

Sheep Origins

The oldest tamed sheep remains in Africa (7500 BP – 7000 BP) were found in the eastern Sahara, the Nile Delta, and the Red Sea Hills. Tamed sheep, possibly from the Sinai Peninsula (7000 BP), might have moved from the Levant to Libya (6500 BP – 6800 BP) due to climate changes and water shortages. Then they moved to the central Nile River Valley (6000 BP), then to the Central Sahara (6000 BP), and finally into West Africa (3700 BP).

Pastoral Rock Art and People's Lives

Pastoral rock art, both engraved and painted, is the most common type of Saharan rock art. It's found at thousands of archaeological sites, often with art from different periods (like Wild Fauna, Round Head, Horse, Camel) at the same place. Almost 80% of these sites are in rockshelters. Cattle herders in the Central Sahara, like those in the Acacus region, built impressive monuments. Later Pastoral rock art often covers earlier Round Head rock art. The Pastoral rock art tradition might have lasted from 7000 BP to 4000 BP, reaching its peak around 6000 BP.

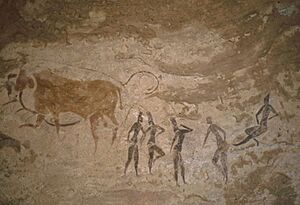

Pastoral rock art is different from Round Head rock art. While Pastoral art mostly shows pastoralists and hunters with bows in scenes of animal care, Round Head art is more about spiritual or celestial themes. Various large stone structures (like alignments, crescents, and stone mounds) existed in the Central Sahara from the Middle Pastoral Period until the Garamantes. Cattle sculptures, which might have been religious symbols, were also made during the Pastoral Period.

In ancient times, people with different body types lived in West Africa and North Africa, including the Central Sahara and Eastern Sahara. There are many types of stone structures in Niger. The most common type of stone mound (tumuli) at Adrar Bous in Niger is the platform tumuli. The second most common is the cone-shaped tumuli.

Some believe that the older "black-face rock art style" of Tassili art is culturally similar to the Fulani people. Proto-Berbers, who are thought to have moved into the Central Sahara from Northeast Africa, have been linked to the later "white-face rock art style" (showing pale-skinned figures, beads, long dresses, and cattle activities) that appeared in Tassili N’Ajjer around 3500 BCE. The earliest platform tumuli developed in the Central Sahara around 3800 BCE. This has been seen as a cultural practice brought by Proto-Berbers. However, there are problems with this idea. The skeletal types in the Central Sahara don't match those of Northeast Africa until after 2500 BCE, and platform tumuli began in Niger around 3500 BCE.

The tumuli tradition in the Central Sahara likely developed from different cultural and ethnic groups interacting, as shown in the rock art. This happened as the Central Saharan environment changed. The early Central Saharan pastoral culture, with its social organization, helped lead to the later development of states in West Africa, Nubia, and the Sahara.

Around 10,000 BP, the monsoon rain system from Sub-Saharan western Africa shifted north into the Central Sahara. As the monsoon moved north, it brought a savanna environment, similar to parts of modern Kenya or Tanzania. Along with this, black African hunter-gatherers also moved north into the Central Sahara (like the Uan Muhuggiag rock shelter in the Acacus Mountains, Libya). Later, around 7000 BP, pastoralists moved into the Central Sahara with their animals. These pastoralists might have come from the Near East and the Eastern Sahara. Saharan pastoral culture spread across northern Africa. At Uan Muhuggiag, the pastoral culture, described as mixed race, might have started even before 5500 BP. The region had various plants and animals like hippos, crocodiles, elephants, and giraffes.

At the Uan Muhuggiag rock shelter, around 5600 BP, a two-and-a-half-year-old boy was mummified using advanced methods. He was a Sub-Saharan African boy, identified by his skull and dark skin. He was buried with a necklace made from ostrich eggshells. This might mean it was a caring, ceremonial burial related to the afterlife. This child mummy is the earliest dated mummy in Africa, possibly a thousand years older than ancient Egyptian mummies. It might be part of a Central Saharan mummification tradition that existed even earlier.

At Mesak Settafet, there was engraved rock art showing cattle and human figures with animal heads (like jackal/dog masks). There was also evidence of a cattle culture, especially near a circle of stone monuments, where cattle were sacrificed and pottery was offered. In the Nile Valley region of Sudan, decorated Saharan pottery, dated to 6000 BP, was found. This pottery was different from the local undecorated pottery.

Since Central Saharan cattle pastoral culture appeared thousands of years before it peaked in the Nile Valley, it might have influenced the later development of ancient Egypt. This includes pottery decoration, cattle pastoralism, and funerary culture, like the god Anubis. Even though the people of Uan Muhuggiag might have left the region due to increasing dryness, it's more likely that knowledge from the Central Saharan pastoral culture spread to the Nile Valley through cultural diffusion around 6000 BP.

Pastoralism, possibly with social classes, and Pastoral rock art appeared in the Central Sahara between 5200 BCE and 4800 BCE. Burial monuments and sites, possibly in areas ruled by chiefs, developed in the Saharan region of Niger between 4700 BCE and 4200 BCE. Cattle burial sites developed in Nabta Playa (6450 BP), Adrar Bous (6350 BP), and other places. By this time, cattle religion (with myths and rituals) and gender roles had developed. For example, men were linked to bulls, hunting, and dogs, and were buried at monumental sites. Women were linked to cows, birth, and possibly the afterlife.

Large stone monuments (megaliths) developed as early as 4700 BCE in the Saharan region of Niger. These monuments might have been early versions of the mastabas and pyramids of ancient Egypt. During Predynastic Egypt, tumuli were present at various locations. Between 7500 BP and 7400 BP, during the Late Pastoral Neolithic, religious ceremonies and burials with megaliths might have set a cultural example for the later worship of the goddess Hathor in ancient Egypt.

By at least 4000 BCE, painted rock art in Tassili n’Ajjer suggests that Proto-Fulani culture might have been present there. The Agades cross, a fertility charm worn by Fulani women, might be linked to a hexagon-shaped jewel shown in rock art at Tin Felki. A finger depiction at Tin Tazarift might refer to the hand of Kikala, the first Fulani pastoralist. At Uan Derbuaen rockshelter, one painting might show the Lotori ceremonial rite of West African Fulani herders. This yearly ceremony, held by Fulani herders, celebrates the ox and its origin in water. It promotes the health and reproduction of cattle by having them cross through a gate of plants, ensuring the wealth of the nomadic Fulani. This interpretation, along with other evidence, suggests that modern Fulani herders are descendants of people from the Sahara. As the Sahara became drier during the Pastoral Period, Pastoral rock artists (like the Fulani) moved into Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Mali.

After moving from the Central Sahara, the Mande peoples of West Africa established their farming and animal-raising civilization of Tichitt in the Western Sahara by 4000 BP. The painted Pastoral rock art of Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria, and engraved art of Niger look similar to the engraved cattle in the Dhar Tichitt rock art in Akreijit. The engraved cattle art of Dhar Tichitt, displayed in enclosed areas that might have been used to pen cattle, suggests that cattle had ritualistic importance for the people of Dhar Tichitt.

Early Pastoral Period Life

In the Tadrart Acacus, a dry period around 8200 BP followed the time of Late Acacus hunter-gatherers. This dry period led to the arrival of Early Pastoral peoples. The Early Pastoral Period was from 6300 BCE to 5400 BCE. Tamed cattle were brought to the Central Sahara. This gave people a chance to become more important, have extra food, and gain wealth. Because of this, some hunter-gatherers in the Central Sahara started to raise cattle. In return, these hunter-gatherers shared knowledge about using plants with the new Early Pastoral peoples. In the Tadrart Acacus, most settlements were in enclosed spaces. Early Pastoral peoples might have lived in open plains to gather food and access water, and in mountains with rockshelters during dry seasons.

Early Pastoral peoples left behind pottery made from sandstone, which was different from the pottery of the Late Acacus. They also left bone tools that might have come from tamed cattle. Early Pastoral rock art is sometimes found on top of older Round Head rock art. Rockshelters in the Tadrart Acacus region might have been important places for women and children, as their burial sites were mainly found there. Engraved rock art has been found on various stone structures in the Messak Plateau.

At Takarkori rockshelter, Early Pastoral peoples used fireplaces between 7400 BP and 6400 BP. They started a tradition of using rockshelters as special burial places for the dead (especially women and children). This practice stopped by the time of the Middle Pastoral peoples. Early Pastoral peoples buried more of their dead, partly because they lived seasonally and might have found earlier burials. They buried their dead under stone-covered mounds (tumuli).

Middle Pastoral Period Life

During and after a dry period in the Acacus region (7300 cal BP and 6900 cal BP), Middle Pastoral peoples and Early Pastoral peoples interacted. This led to them merging, with Middle Pastoral peoples eventually replacing Early Pastoral peoples.

The Middle Pastoral Period (5200 cal BCE – 3800 cal BCE) is when most of the Pastoral rock art was made. In the Messak region of Libya, cattle remains were found near engraved Pastoral rock art showing cattle. This suggests rituals of cattle sacrifice. Stone monuments are also often found near this art. A full cattle-raising economy, including dairying, developed in the Acacus and Messak regions. Middle Pastoral peoples used semi-settled camps seasonally, depending on the monsoon rains.

At Wadi Bedis, 42 stone monuments were found, including stone structures and mounds. Pottery and stone tools were found with 9 monuments that had engraved rock art. From 5200 BCE to 3800 BCE, animals were buried. Some stone maces, used to kill cattle for ceremonies, were placed near the heads of sacrificed cattle or stone monuments. These ceremonies happened over several centuries. Goats or other hoofed animals were also found. The reason for these cattle sacrifices is not certain, but they might have happened when different pastoral groups gathered. This whole system has been called an African Cattle Complex.

At the Uan Muhuggiag rockshelter, the child mummy of Uan Muhuggiag was dated to 7438 ± 220 BP from the coal layer it was found in, and to 5405 ± 180 BP from the animal hide it was wrapped in. Another date for the antelope skin hide, found with a grinding stone and an ostrich eggshell necklace, is 4225 ± 190 BCE.

At Takarkori rockshelter, Middle Pastoral peoples developed a complete cattle-based economy (including pottery and milking) between 6100 BP and 5100 BP. These people, who lived in rockshelters seasonally, buried their dead in pits at different depths. Thirteen human remains were found at Takarkori rockshelter, including two naturally mummified females, dated to the Middle Pastoral Period (6100 BP – 5000 BP). These two naturally mummified women were the earliest mummies studied in detail.

Around 5000 BP, the building of large stone megalithic monuments increased in the Central Sahara. The tradition of building stone mounds (tumuli) started in the Middle Pastoral Period and changed during the Late Pastoral Period (4500 BP – 2500 BP).

Late Pastoral Period Life

During the Late Pastoral Period, rock art in the Central Sahara showed fewer animals from modern savannas. Instead, it showed more animals suited for dry environments. Rockshelters in mountains were used less often, and lakes in plains areas started to become dry salt flats (sebkhas). This led to people moving more often and spreading out their settlements across many areas. Some stones and pottery, as well as evidence of sheep and goat raising, have been found at Late Pastoral Period sites. At Takarkori rockshelter, between 5000 BP and 4200 BP, Late Pastoral peoples herded goats seasonally. They also started a long tradition of building large stone monuments as burial sites. These sites were usually away from where people lived.

Final Pastoral Period Life

The Final Pastoral Period (1500 BCE – 700 BCE) was a time of transition. People moved from being nomadic herders to settling down more. Final Pastoral peoples were scattered groups who moved their animals seasonally. They created burial mounds of different shapes and sizes. They kept small animals like goats and used more plants. At Takarkori rockshelter, Final Pastoral peoples created burial sites for hundreds of individuals around 3000 BP. These sites had special items from far away and unique drum-shaped buildings. This period led to the development of the Garamantian civilization. Final Pastoral peoples were in contact with the Garamantes. Later, the Garamantes gained control over the oasis-based economy in southern Libya.

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |