Round Head Period facts for kids

The Round Head rock art is the oldest type of painted rock art found in the central Sahara Desert. These amazing paintings were mostly made between 9,500 and 7,500 years ago, and they stopped being created around 3,000 years ago. This period came after the Kel Essuf Period and before the Pastoral Period. There are thousands of Round Head artworks across the Central Sahara.

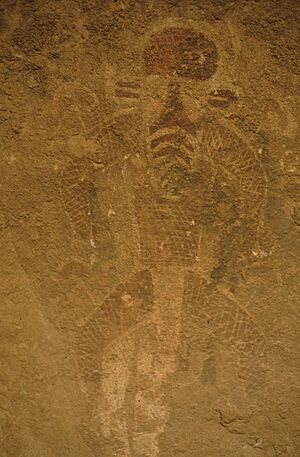

These paintings often show people and wild animals like the Barbary sheep and antelope. They include many interesting details, such as people dancing, taking part in ceremonies, wearing masks, and showing spiritual animal forms. Interestingly, Round Head painted art and Kel Essuf engraved art are often found in the same areas, and sometimes even in the same rock shelters! The Round Head art found in Tassili and nearby mountains looks a lot like traditional Sub-Saharan African cultures.

Around 10,000 years ago, during a time called the Epipaleolithic period, early hunter-gatherers used the walls of rock shelters (like Tin Torha) to build simple huts where families lived. They also made hearths (fireplaces). These shelters were good for their lifestyle, as they moved around but also stayed in one place for a while. These hunter-gatherers even built a simple stone wall about 10,500 years ago, possibly to block the wind. Around 10,000 years ago, they started processing plants and were very skilled at using Barbary sheep. They also used ceramics (pottery) and stone tools, though not as often.

These Epipaleolithic hunters, who had a complex social system and excellent tools, created the Round Head rock art. Later, semi-settled hunters from the Epipaleolithic and Mesolithic periods, who made beautiful things like stone tools and decorated pottery as early as 10,000 years ago, also created the engraved Kel Essuf and painted Round Head art. You can find this art in parts of Libya (like the Tadrart Acacus), Algeria (especially Tassili n'Ajjer), Nigeria, and Niger.

Contents

Life of the Round Head Artists

The artists who made the Round Head rock art were skilled hunters and gatherers. They also developed pottery, used plants, and managed animals. The Barbary sheep was very important to their culture, as seen by its presence in Round Head art across the Central Sahara. These sheep were even kept in stone pens near Uan Afuda cave, starting about 9,500 years ago. This continued until the beginning of the Pastoral Neolithic period in the Sahara.

Between 7,500 BCE and 3,500 BCE, during a time known as the Green Sahara (when the desert was much wetter), hunter-gatherers near the Takarkori rock shelter farmed, stored, and cooked wild Saharan plants. They also tamed animals like Barbary sheep, milking and managing them. This also continued until the start of the Pastoral Neolithic.

Between 8,800 and 7,400 years ago, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers hunted different animals. They used many grinding and flaking stone tools, along with ceramics, to help them gather more wild plants. They used ceramics more as they settled down and gathered more plants. At Uan Afuda, settlements from this time show remains of baskets with wild plants and cords, dating back to 8,700 to 8,300 years ago.

Types of Rock Art

Rock art in the Sahara is divided into different groups. These groups include Bubaline, Kel Essuf, Round Heads, Pastoral, Caballine, and Cameline. They are classified based on how the art was made, what animals or people are shown, the patterns used, and if one painting is on top of another.

Around 5,000 years ago, a large type of buffalo called Bubalus antiquus became extinct in Africa. Because of this, the engraved stone pictures of these huge wild buffalo in open rock areas are called Bubaline art. In contrast, Kel Essuf art (meaning "spirit of dead" in the Tuareg language) is found in enclosed rock areas. These engravings show small human figures with short arms and legs.

Round Head art usually shows people and wild animals like Barbary sheep and antelope. These paintings often include details like dancing, ceremonies, masks, and spiritual animal forms. Round Head painted art and Kel Essuf engraved art are often found in the same areas. However, Bubaline engraved art is rarely found in the same places where Round Head art is common.

Pastoral rock art, which can be engraved or painted, is different from Round Head art because it shows domesticated cattle. These different images suggest that new groups of people entered the region. As the Green Sahara became drier, later rock art (like Pastoral, Camelline, and Caballine) shows fewer large wild animals and more one-humped camels and horses.

When Was the Art Made?

The exact dates for Saharan rock art have been a big topic of discussion among experts. The oldest types, like Round Head, Kel Essuf, and Bubaline art, have been harder to date precisely compared to newer art that shows animals from specific time periods. Because of this, two main timelines were created: a "high chronology" (older dates) and a "low chronology" (newer dates).

Bubaline rock art is thought to be from the late Pleistocene or early Holocene periods. This is based on traces of clay and iron found in the dark layers on the rock. Organic materials found deep within the rock walls suggest dates between 9,200 and 5,500 years ago. The Qurta petroglyphs in prehistoric Egypt, which show wild animals, are at least 15,000 years old. This also suggests that Bubaline art could be much older than 10,000 years.

Kel Essuf art has not been found on top of Bubaline art, but it has been found underneath Round Head art. Because of this layering and the artistic similarities between Kel Essuf and Round Head art, Kel Essuf engravings are believed to be the earlier style that led to the painted Round Head art.

Evidence for the older "high chronology" includes decorated Saharan pottery from 10,726 years ago. Tools with red paint (ochre) were found in a rock shelter with Round Head art, showing that painting was happening. Paint from Round Head art in Libya was also tested and dated to 6,379 years ago. All this suggests that the Round Head art tradition continued for a long time, even into the Pastoral Period.

Most experts believe that Round Head artists created their art between 9,500 and 7,500 years ago.

Climate and Environment

The Aterian culture existed from about 60,000 or 40,000 years ago to 20,000 years ago. Between 16,000 and 15,000 years ago, the environment was wet. From 20,000 to 13,000 years ago, the climate varied a lot. High mountain regions were much wetter than lower areas without mountains. This meant mountains had a lot of rainfall, forming lakes, while lower areas were very dry. During the late Pleistocene period, the mountainous areas stayed wet enough to support animals, plants, and people.

Where Round Head Art Began

A researcher named Mori first suggested in 1967 that Round Head art developed from Kel Essuf art in the Acacus region. This idea is supported because Round Head art has been found painted on top of Kel Essuf art in Algeria. This layering suggests that Kel Essuf art came first and that Round Head art evolved from its simpler engravings to more detailed paintings. Other researchers have also supported Mori's idea.

Kel Essuf and Round Head art share many similarities, including shapes like a "half-moon" connected to shoulders, figures with bows and sticks, and horns on heads that look alike. These shared features are not found in Pastoral rock art, suggesting they were unique to the hunter-gatherers who made Kel Essuf and Round Head art. Both Kel Essuf and Round Head art mostly show male figures.

Studies comparing art from Tassili n’Ajjer and Djado suggest that the Round Head art of Djado came before the art of Tassili n’Ajjer. It's thought that the artists from Djado moved to Tassili and continued their artistic traditions there.

The "pecked Djado-Roundheads" (which are Kel Essuf art) in the Djado mountains of Niger look very similar to Round Head art in Algeria and Libya. This suggests that the hunting groups who created these artworks were part of the same culture, even if they had some local differences.

While Round Head art is less common in the mountains of Algeria and Libya, it's most abundant in the Tassili plateau. The earliest forms of Round Head art might have come from the northern mountainous areas of Niger. These areas are archaeologically similar, for example, in their pottery. Wild plants and animals were used by hunter-gatherer cultures between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago. The oldest pottery in the Sahara (from 9,420 years ago in Tin Hanakaten) suggests that the core area for ancient ceramics might have been in the shared region of Niger and Algeria. The Round Head artists might have come from this area and shared their culture over long distances. The spread of pottery in the Sahara might be linked to the origins of both Round Head and Kel Essuf art, which are found in the same regions and share similar features.

Round Head Art and Its Creators

Round Head Art Features

Round Head rock art is the earliest painted rock art in the Central Sahara, with thousands of images. In Algeria and Libya, researchers have identified many painted figures, including 149 body images, 85 stick holders, 77 horned figures, and 34 bow bearers. In the Tassili region, there are 55 figures wearing armbands, 43 with "T"-shaped features, and 7 "Great God" images. The Round Head art in Tassili n’Ajjer is found in large rock formations like shelters and canyons. The later Round Head paintings show people with features like strong jaws, big lips, and rounded noses. One painting of a single, tamed cow in the Round Head style might suggest that some of these hunter-gatherers started adopting cattle herding from new groups.

The Round Head art style continued from the Kel Essuf rock art tradition. Unlike Bubaline rock art, which doesn't focus much on humans, Round Head art highlights human figures. This change shows a growing awareness of human importance and might represent a shift in Central Saharan rock art from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic period. Round Head art also shows animals like buffalo, cattle, crocodiles, and fish. Some paintings even show scenes related to agriculture and animal domestication, like a muzzled antelope at Tassili N’Ajjer.

During the early Holocene period, Round Head art was created at Tassili N'Ajjer in Algeria and Tadrart Acacus in Libya. About 70% of these artworks are human-like figures. Both male and female figures have scarification marks, which are different for each gender. Linear patterns are only on male figures, while crescent-shaped and circular patterns are only on female figures. Between 5,000 and 4,000 BCE, a painting of a horned running woman with body scarification was made in Tassili N’Ajjer. She might have been a goddess or a dancer.

The Hunter-Gatherers

The hunter-gatherers of the Central Sahara, like those in the Acacus region, had a sense of creating grand, important art. While there weren't large buildings for living or rituals in the early Holocene, Round Head rock art can be seen as monumental art from that time. It's also possible that some hunter-gatherers in the Central Sahara didn't create any rock art.

The people who created the Round Head rock art had dark skin. These dark-skinned groups were different from the Tuareg Berbers. Long-time Tuareg residents of the area also believed that the Round Head art was made by black people who lived in the Tassili region a long time ago. Skin samples from human remains in the Acacus and Tassili regions confirmed that these ancient people had dark skin.

At the Uan Muhuggiag rockshelter in the Acacus region, a child mummy (from about 5,400 years ago) and an adult (from about 7,800 years ago) were found. At the Tin Hanakaten rockshelter in Tassili n'Ajjer, a child (from about 7,900 years ago) with a specially shaped head was found, along with another child and three adults (from about 9,400 years ago). Studies of these remains confirmed that these Central Saharan people from the Epipaleolithic, Mesolithic, and Pastoral periods had dark skin. One researcher concluded that "Black people of different appearance were therefore living in the Tassili and most probably in the whole Central Sahara as early as the 10th millennium BP."

Their Way of Life

Around 10,000 years ago, during the Epipaleolithic period, families lived in huts built against rock shelter walls. They also had hearths (fireplaces), which suited their semi-nomadic lifestyle. They built simple stone walls, possibly as windbreaks. These hunter-gatherers processed plants and specialized in using Barbary sheep. They also used pottery and basic stone tools. They hunted Barbary sheep and other animals and used ceramics and stone tools between 10,000 and 8,800 years ago. These hunters, with their advanced social organization and tools, created the Round Head rock art.

In the Tadrart Acacus region of Libya, hunter-gatherers might have started living there between 10,721 and 10,400 years ago. They lived in various spots at Tin Torha, using bones, shiny stone items, ostrich eggshells, and pottery. They also used more plants, along with grinding tools and pottery for boiling. The earliest bone tools found date back to around 9,700 years ago.

Many bone tools were found at Torha East, made from animals like Barbary sheep, birds, and gazelles. A decorated bone tool might have been a symbol of leadership. They shaped bones using stone tools like blades and flakes. This process happened locally, and the same stone tools might have been used to grind ochre (red paint) and process plants. The designs on bone tools might reflect patterns from basket weaving and pottery found in the Acacus region.

The unique designs on bone objects (like hourglass-shaped items, spatulas, and pendants) show the skill of the Tin Torha hunter-gatherers. These objects might have been used as symbols of group identity and for trading with other groups.

The Round Head artists, who had a complex culture, hunted and gathered, developed pottery, used plants, and managed animals. The importance of shepherded Barbary sheep is clear from their presence in Round Head art across the Central Sahara. Barbary sheep were kept in stone pens near Uan Afuda cave from about 9,500 years ago until the start of the Pastoral Neolithic period. Between 7,500 and 3,500 BCE, during the Green Sahara, wild plants were farmed, stored, and cooked, and tamed animals like Barbary sheep were milked and managed by hunter-gatherers.

Between 8,800 and 7,400 years ago, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers hunted various animals and used many stone tools and ceramics to gather more wild plants. They used ceramics more as they settled down and gathered more wild plants. At Uan Afuda, Mesolithic settlements had remains of baskets with wild plants and cords, dating back to 8,700 to 8,300 years ago.

Before cattle herders arrived in Jebel Uweinat between 4,400 and 3,300 BCE, African hunter-gatherers might have created the painted Round Head rock art there. As the Green Sahara became a desert, the creation of Round Head paintings stopped by 3,000 years ago.

Connections to African Cultures

The Round Head rock art of Tassili and nearby mountains shares many similarities with traditional Sub-Saharan African cultures. One key aspect of these cultures is their strong values, which remain even when their way of life changes. For example, women's role in raising children and men's role in ceremonies stay important. The creators of the Round Head rock art had dark skin and were different from the Tuareg Berbers.

Traditional Sub-Saharan African cultures have clear links to Round Head rock art. For instance, men often lead the main ceremonies in these cultures, while women might not gain deep sacred knowledge or participate in many ceremonies. This cultural practice, where men are the main participants in ceremonies and hold spiritual knowledge, matches the fact that 95% of Round Head rock art depicts men.

Masks are a common theme in both Round Head rock art and modern African cultures. Only a select group of men (like male relatives of the deceased or initiated men) are allowed to touch secret masks. The way Round Head art in Tassili was painted over repeatedly is similar to how young male initiates in Mali repaint rock shelters where masks are kept, among the Dogon people.

Body painting is a vital part of ceremonies for young male and female initiates in Sub-Saharan Africa. The symbols in body painting are often used to ask spirits for good reproduction and safety. Young male initiates receive a stick as a symbol of peace and wisdom, and later, initiated men receive a bow as a hunting symbol. Traditional Sub-Saharan African cultures often use horn symbols to represent fertility and growth. Similarly, Round Head rock art might have been created in special rock shelters by individuals undergoing ceremonial rites. The bands worn by 90% of male Round Head figures might have been for spiritual protection, similar to how the Songhai of Niger wear large rings for security against harm.

There are also strong connections between Round Head art and the roles of women in Sub-Saharan African cultures. In many traditional cultures, men are usually the main leaders of ceremonies, while women play important, but secondary, roles. Men are often the main actors in ceremonies for healing, fire, or rainmaking, while women contribute musically, vocally, and rhythmically.

Common themes in Round Head art and Sub-Saharan African cultures include animals with heads pointing down and powerful gods. Down-headed animals, which appear in South African rock art and represent animal sacrifice for rain rituals, also appear in Round Head art. In the Round Head art of Tassili, powerful gods are shown in the center of rock shelter walls. Similarly, in Sub-Saharan African cultures, rocks and caves are often believed to be home to spirits, and tall mountains are seen as homes of the divine.

These many similarities, which are not found in modern North African cultures, are present in Round Head paintings and modern Sub-Saharan African cultures. Saharan ceramics look very similar to the oldest ceramics found in Djenne-Djenno, dating back to 250 BCE. The egalitarian (equal) civilization of Djenne-Djenno was likely founded by the ancestors of the Bozo people. The masks in Round Head paintings closely resemble masks in modern Sub-Saharan African cultures. In parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, especially in Mali, Niger, and Chad, the traditional cultures are very conservative. Symbols found in Round Head paintings are also found in these cultures, which might show a continuous cultural link.

At Jebel Uweinat, Round Head rock art mostly shows human figures, with few depictions of wild animals or hunting scenes (except for a giraffe). About 9% of the art shows archers with bows and arrows. Some parts of the colorful human figures, which might have had body decorations, were red, while other parts (like loincloths, accessories, hairstyles, bows, and armbands) were white. At least 43% of the Round Head art at Jebel Uweinat shows traditional African dance.

Like in traditional African cultures (with tattoos and scarification), some human figures might have had body modifications (like facial tattoos) and hairstyles (like chignons). Only 2% of the human figures have hands and fingers, and some might have closed fists. The human figures generally have thick, muscular arms and legs. Both men and women are shown, though women make up only about 4% of the human figures. Some rare images might show a mother and her children, or two supernatural individuals.

Out of 146 different ways human figures were shown:

- 35% were standing with symmetric arms.

- 16% were standing with asymmetric arms.

- 16% were bent on their knees.

- 11% had one leg free.

- 11% were running or walking.

- 10% were kneeling or sitting.

- 1% were jumping or tiptoeing.

Among the figures with symmetric arms, some are in combat-ready poses. Others are in an "A-pose," which is common in Round Head art at Uweinat. In West African art, this pose means a person is alive, and in African dance, it's a starting stance that means unlimited expression. Among figures with asymmetric arms, one man has an extended arm and clenched fist, with the other arm drawn back for a strike. There's also a scene that might show an adult protecting two children.

Among the figures bent on their knees, some are semi-squatted. These figures might be showing a traditional African dance technique called "getting down," found across Sub-Saharan Africa and among the African diaspora. There's also a scene showing African dance, likely involving an important person. The most notable bent-on-knees figures show two dancing individuals with white halos around their heads, which might mean they reached a special spiritual state through energetic, rhythmic African dance.

Figures with one leg free show African dance with squat-and-kick movements. Two women with chignon hairstyles are shown doing what might be choreographed African dance. Among running/walking and jumping/tiptoeing figures, some have chignons. More figures are shown sitting than kneeling.

What They Left Behind

The Algerian Tadrart and Tassili, and the Libyan Acacus regions of the Sahara, are rich in ancient rock art like paintings and petroglyphs. This area was first settled by gatherers and hunters around 10,000 years ago, and then by cattle herders around 7,500 years ago, leading to pastoralism. As the desert grew, cattle and sheep herders, who once lived in higher mountain areas, likely moved to lower areas near lakes for part-time settlement before 5,000 years ago. After 5,000 years ago, pastoralists used both high and low areas seasonally. They used stone grinding tools, simple ceramics, and resources from far away more often.

Since cattle pastoralism existed in the Sahara from 7,500 years ago, Central Saharan hunters and herders might have lived together for a long time. As the desert grew, people likely migrated from the Central Sahara (where Round Head paintings are found) towards Lake Chad and the Niger Delta. While some moved south of the Sahara, other Central Saharan hunter-gatherers might have adopted pastoralism (herding cattle and goats). This change allowed them to gain social status, produce extra food, and gather wealth. In return, Central Saharan hunter-gatherers shared knowledge about using plants (like Cenchrus and Digitaria) with the incoming early pastoral peoples.

The migration of hunter-gatherers and cattle herders out of the Central Sahara happened as the Green Sahara became a desert around 4,000 years ago. Seasonal waterways were likely the paths they took to the Niger River, Chad Basin, and Nile Valley. People started settling in the Sahelian region as older settlements and burial sites in northern Niger were no longer used. The movement of Central Saharan people into the Sahelian region of Sub-Saharan Africa is confirmed by Saharan-influenced pottery found there.

As late as 2,500 years ago, some groups from the Round Head period might have continued to live as hunters in the Central Sahara. The Greek historian Herodotus identified Central Saharan hunter-gatherers during the Horse period as "Aithiopian Troglodytes," who were said to be pursued by the Garamantes. However, contrary to the idea that North Africans (like the Garamantes) captured and enslaved Sub-Saharan West Africans using chariots in ancient times, there were fair trades of materials (like gold) between Sub-Saharan West Africans and North Africans (like the Carthaginians).

Images for kids

-

Round Head figures and zoomorphic figures, including a Barbary sheep

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |