Dairy farming facts for kids

Dairy farming is a type of agriculture that focuses on producing milk. This milk is then used to make many dairy products like cheese, butter, cream, and yogurt. Dairy farming has a long history, starting around 9,000 years ago in parts of Europe and Africa. For a long time, cows were milked by hand on small farms. But in the 1900s, new inventions like rotary parlors and automatic milking systems made it possible for large farms to milk many more cows.

Keeping milk fresh has also gotten much better. In the late 1800s, refrigeration technology arrived. This helped dairy farms keep milk from spoiling by slowing down bacterial growth.

Today, countries like India, the United States, China, and New Zealand are big players in the dairy world. They produce, sell, and buy a lot of milk. The amount of milk produced globally has generally increased. In 2017, about 827 million tonnes of milk were produced worldwide.

However, there are also concerns about dairy farming's impact on the environment. This includes managing manure and air pollution from methane gas. The industry's role in greenhouse gas emissions is also linked to environmental changes. Farmers are working on ways to control waste. Some people are also concerned about the health of dairy cows on very large farms.

Contents

Common Dairy Animals

While many mammals can produce milk, most commercial dairy farms focus on one type of animal. In many developed countries, dairy farms mostly have high-producing dairy cows. Other animals used for dairy farming include goats, sheep, water buffaloes, and camels. In Italy, some farms are even raising donkeys to produce milk, especially for babies who might have allergies to cow's milk.

History of Dairy Farming

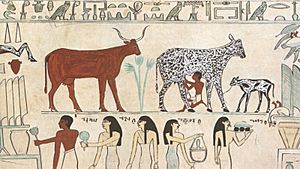

Cattle were first tamed about 12,000 years ago for food and to help with work. But the first signs of using cows for milk production come from about 9,000 years ago in what is now Turkey. Dairy farming then spread to other parts of the world. It reached Eastern Europe around 8,000 years ago, Africa 7,000 years ago, and Britain and Northern Europe 6,000 years ago.

In the last century, larger farms that focus only on dairy have become common. Big dairy farms work best where a lot of milk is needed to make products like cheese or butter. They also thrive where many people want to buy milk but don't own cows themselves.

Milking by Hand

Dairy farming often grew around towns and cities. People living in cities usually didn't have space for their own cows. Farmers nearby could earn extra money by selling milk in town. They would fill barrels with milk in the morning and take them to market. Until the late 1800s, all milking was done by hand. Even on larger farms with hundreds of cows, one person could only milk about a dozen cows a day. So, most farms were small.

Most herds were milked indoors twice a day. The cows were tied in a barn. They could also be fed while being milked. Many dairy cattle would graze in pastures during the day between milkings. Some old dairy farms are now historic sites, showing how things used to be. For example, Point Reyes National Seashore has one such farm.

Dairy farming has been part of agriculture for thousands of years. Historically, it was just one part of small, mixed farms. But in the last 100 years, larger farms specializing in dairy have appeared. These big farms are the best way to meet the demand for milk today.

Vacuum Bucket Milking

The first milking machines were like an extension of the traditional milk pail. These early machines sat on top of a regular milk pail on the floor under the cow. After each cow was milked, the bucket was emptied into a larger tank. These machines started being used in the early 1900s.

Later, the "Surge hanging milker" was invented. A wide leather strap was placed around the cow's lower back. The milking device and collection tank hung from this strap under the cow. This invention allowed the cow to move more naturally while being milked.

Milking Pipeline

The next big step in automatic milking was the milk pipeline, which came out in the late 1900s. This system uses a permanent pipe to carry milk and another pipe for vacuum. These pipes go around the barn or milking parlor above the cows. Small ports allow the milking device to connect to the pipes. This meant farmers no longer needed to carry heavy milk containers. The milking device became smaller and lighter.

The milk is pulled into the milk pipe by the vacuum system. Then, it flows by gravity to a storage tank. This pipeline system greatly reduced the hard work of milking. It meant farmers didn't have to carry big, heavy buckets of milk from each cow.

The pipeline system allowed barns to become much longer. But eventually, farmers started milking cows in large groups. They would fill the barn with a third or half of the herd, milk them, then empty and refill the barn. As herds grew even bigger, this led to the more efficient milking parlor.

Milking Parlors

Milking parlors (also called 'cowsheds' in Australia and New Zealand) were designed to milk more cows with fewer people. They make milking like an assembly line. They also reduce physical strain on farmers by placing cows on a platform slightly above the milker. Many older, smaller farms still use tie-stall barns. But worldwide, most commercial farms now have parlors.

Herringbone and Parallel Parlors

In herringbone and parallel parlors, the milker usually works on one row of cows at a time. Cows are moved from a holding area into the parlor. The milker attaches the machines to each cow in that row. Once all the machines are removed, the cows are released. A new group of cows then enters the empty side, and the process repeats. These rows can hold from four to sixty cows. Herringbone parlors are easy to maintain, durable, and safer for animals and people than tie stalls. The first herringbone shed was built in 1952 in New Zealand.

Rotary Parlors

In rotary parlors, cows step onto a rotating platform one at a time. One milker stands near the entry to clean the cow's teats. The next milker attaches the machine. By the time the platform almost completes a full circle, the cow is done milking, and the machine comes off automatically. The last milker cleans the teats again to protect them. Then, the cow steps off the platform and returns to the barn. Rotary cowsheds started in New Zealand in the 1980s. They are more expensive than herringbone sheds.

Automatic Milker Take-off

It can be bad for a cow to be milked for too long after she has stopped giving milk. So, milking involves not just putting on the milker, but also knowing when to take it off. While parlors allowed farmers to milk many more animals quickly, it also meant more animals to watch. The automatic take-off system was created to remove the milker when the milk flow drops to a certain level. This frees the farmer from having to watch many animals at once.

Fully Automated Robotic Milking

In the 1980s and 1990s, robotic milking systems were developed, mainly in Europe. Thousands of these systems are now used every day. With these systems, cows can choose when they want to be milked throughout the day. When a cow enters the milking unit, she gets food. Her collar is scanned to record information about her milk production.

History of Milk Preservation Methods

Keeping milk cold has always been the main way to keep it fresh longer. When windmills and well pumps were invented, one of their first uses on farms was to cool milk. This helped milk last until it could be taken to the town market.

Cold underground water was continuously pumped into a cooling tub. Tall, ten-gallon metal containers of warm, fresh milk were placed in this cold water. This method was popular before electricity and refrigeration became common.

Refrigeration

When refrigeration equipment first arrived, it was used to cool cans of milk. These cans were placed in a cold water bath to remove heat and keep them cool until they could be collected. As milking became more automated, hand milking and milk cans were replaced by bulk milk coolers.

"Ice banks" were the first type of bulk milk cooler. These were tanks with two walls. Evaporator coils and water were between the walls. A small refrigeration machine would cool the coils. Ice would build up around the coils. When milking started, only a milk agitator and water pump were needed to cool the incoming milk to below 5 degrees Celsius.

This method worked well for smaller dairies. However, it wasn't very efficient for larger milking parlors. In the mid-1950s, "direct expansion refrigeration" was used directly in bulk milk coolers. This system has an evaporator built into the tank's inner wall to remove heat from the milk. Direct expansion cools milk much faster than ice bank coolers. It is still the main way to cool milk in bulk tanks on small to medium-sized farms today.

Another important invention for milk quality is the plate heat exchanger (PHE). This device uses many special stainless steel plates with small spaces between them. Milk flows between some plates, and cold water flows between others. This quickly removes a lot of heat from the milk, which greatly slows down bacteria growth and improves milk quality. Cold ground water is often used for cooling. Dairy cows drink about 3 gallons of water for every gallon of milk they produce. They prefer slightly warm water over cold ground water. So, PHEs can also provide warm water for the cows, which can increase milk production.

Plate heat exchangers have also changed as dairy farms have grown. As a farm gets bigger, its milking parlor needs to handle more milk. This means a huge increase in milk flow and cooling needs. Today's largest farms produce milk so fast that direct expansion systems can't cool it quickly enough. PHEs are used to rapidly cool the milk to the right temperature before it reaches the bulk tank. Often, ground water cools the milk first. Then, a second (and sometimes third) part of the PHE uses a mix of chilled water and propylene glycol to remove the rest of the heat. These systems can cool very large amounts of milk quickly.

Milking Operation

Milking machines are held in place by a vacuum system. This system lowers the air pressure inside the machine. The vacuum also lifts milk vertically through small hoses into a receiving can. A milk pump then moves the milk from the receiving can through stainless steel pipes, through the plate cooler, and into a refrigerated bulk tank.

Milk is taken from the cow's udder by flexible rubber parts called liners. These liners are inside a rigid air chamber. Air and vacuum are pulsed into this chamber. When air enters the chamber, the vacuum inside the liner makes it collapse around the cow's teat. This squeezes the milk out, much like a baby calf's mouth does. When the vacuum returns, the liner relaxes and opens, ready for the next squeeze.

It takes an average cow three to five minutes to give her milk. Some cows are faster or slower. Slow-milking cows might take up to fifteen minutes. Milking speed doesn't affect milk quality, but it does affect how the milking process is managed. Since most farmers milk cows in groups, the group can only go as fast as the slowest cow. Because of this, farmers often group slow-milking cows together.

The milk goes through a strainer and plate heat exchangers before entering the tank. There, it can be stored safely for a few days at about 40°F (4°C). At set times, a milk truck arrives and pumps the milk from the tank. It is then taken to a dairy factory to be pasteurized and made into many products. How often milk is picked up depends on how much milk the farm produces and how much it can store. Large dairies might have milk picked up once a day.

Management of the Herd

The dairy industry is always changing. New technology and rules help farms become more efficient and better for the environment. Management styles can be "intensive" (high input, high output) or "extensive" (low input, low output). These styles, along with technology, local rules, and weather, affect how farms manage feeding, housing, health, breeding, and waste.

Most modern dairy farms divide their animals into different groups. These groups are based on age, how much food they need, if they are pregnant, and how much milk they are producing. The group of cows currently giving milk (the milking herd) is often managed very carefully. This ensures their diet and living conditions help them produce as much high-quality milk as possible. Some farms divide the milking herd further into "milking strings" based on their food needs. Cows that are resting before having their next calf are called "dry cows" because they are not being milked. All female animals that haven't had their first calf yet are called "heifers." Some heifers will become part of the milking herd. Other calves, especially most males, are raised for meat, like veal.

Housing Systems

Dairy cattle housing systems vary a lot around the world. They depend on the climate, farm size, and feeding methods. Housing must provide food, water, and protection from extreme weather. Heat can reduce a cow's ability to have calves and produce milk. Providing shade is a common way to reduce heat stress. Barns might also have fans or special ventilation. Very cold conditions, while rarely deadly, make cows need more energy to stay warm. This means they eat more and produce less milk. In winter, where it's cold enough, dairy cattle are often kept inside barns, which are warmed by their own body heat.

Providing food is also a key part of dairy housing. Pasture-based dairies are a more "extensive" option. Cows graze on grass when the weather is good. Often, their diet needs extra food if the pasture isn't good enough. Free stall barns and open lots are "intensive" housing options. Here, food is brought to the cattle all year round. Free stall barns let cows choose when to eat, rest, drink, or stand. They can be fully enclosed or open-air, depending on the climate. The resting areas, called free stalls, are divided beds with mattresses or sand. The floors in the lanes are often grooved concrete. Most barns open to outdoor corrals, which cattle can use when the weather allows. Open lots are dirt areas with shade structures and a concrete pad where food is delivered.

Milking Systems

Life on a dairy farm often centers around the milking parlor. Each cow that is giving milk will visit the parlor at least twice a day to be milked. A lot of engineering has gone into designing milking parlors and machines. Being efficient is very important. Every second saved while milking one cow adds up to hours for the whole herd.

Milking Machines

Milking is now almost always done by machine, though people are still needed on most farms. The most common milking machine is called a "cluster milker." This machine has four metal cups, one for each teat. Each cup is lined with rubber or silicone. The cluster connects to a milk collection system and a pulsing vacuum system. When the vacuum is on, it pulls air from between the outer metal cup and the liner, drawing milk out of the teat. When the vacuum turns off, it lets the teat refill with milk. On most farms, a person attaches the cluster to each cow. But the machine senses when the cow is fully milked and detaches itself.

Milking Routine

Every time a cow enters the parlor, several things need to happen to ensure milk quality and cow health. First, the cow's udder must be cleaned and disinfected. This helps prevent milk contamination and udder infections. Then, the milker checks each teat for signs of infection by looking at the first stream of milk. This process is called "stripping the teat." The milker looks for any odd color or lumps that might mean mastitis, an infection in the cow's mammary gland. Milk from a cow with mastitis cannot be sold for people to drink. So, farmers must make sure infected milk doesn't mix with milk from healthy cows and that the cow gets treatment. If the cow passes the check, the milker attaches the milking cluster. The cluster runs until the cow is fully milked and then drops off. The milk immediately goes through a cooling system and into a large cooled storage tank. It stays there until a refrigerated milk truck picks it up. Before the cow leaves the milking stalls, her teats are disinfected one last time to prevent infection.

Nutritional Management

Feed for cattle is one of the biggest costs for dairy farmers. This feed might come from the land they graze, or from crops they grow or buy. Farmers who use pastures spend a lot of time and effort keeping their pastures healthy. Techniques like rotational grazing are common. Many large dairies that bring food to their cattle have a special nutritionist. This person creates diets that keep animals healthy, produce milk, and save money. For best results, diets must be different depending on the animal's growth, milk production, and pregnancy status.

Cattle are called ruminants because of their special digestive system. They have a helpful relationship with tiny living things in their stomach, called the rumen. This allows them to eat low-quality food. The rumen is like a tiny ecosystem inside each dairy cow. For good digestion, the rumen's environment must be perfect for these tiny living things. So, a nutritionist's job is to feed these microbes, not just the cow.

Cattle's food needs are usually split into "maintenance requirements" (how much food they need to live, based on their weight) and "milk production requirements" (how much food they need to make milk, based on how much milk they produce). The nutrients in each available feed are used to create a diet that meets all needs in the cheapest way. Cows must eat a diet high in fiber to keep the rumen microbes healthy. Farmers often grow their own forage for their cattle. Crops like corn, alfalfa, timothy, wheat, oats, sorghum, and clover are common. These plants are often processed after harvest to keep them fresh or improve their nutrients. Corn, alfalfa, wheat, oats, and sorghum are often fermented to make silage. Many crops like alfalfa, timothy, oats, and clover are dried in the field before being baled into hay.

To give cows more energy, they are often fed cereal grains. In many parts of the world, dairy diets also include byproducts from other farming areas. For example, in California, cattle often eat almond hulls and cotton seed. Using these byproducts can help the environment by keeping these materials out of landfills.

To get all their nutrients, cows must eat their whole meal. But like humans, cattle have favorite foods. To stop cows from only eating the best parts, most farmers feed a total mixed ration (TMR). In this system, all the food parts are well mixed in a special truck before being given to the cattle. Different TMRs are often made for groups of cows with different food needs.

Reproductive Management

Female calves born on a dairy farm are usually raised to replace older cows that are no longer producing enough milk. A dairy cow's life is a cycle of pregnancy and giving milk, starting when she is old enough to breed. The timing of these events is very important for how much milk the farm produces. A cow won't produce milk until she has given birth to a calf. So, timing her first breeding and all later breedings is key to keeping milk production high.

Most cows have one calf at a time. Pregnancy lasts about 280 to 285 days, which is a little less than 9 and a half months.

Lactation Management

After a calf is born, the cow starts to give milk, a process called Lactation. She will usually continue to give milk as long as she is milked, but the amount will slowly go down. Dairy farmers know this pattern well. They carefully time the cow's next breeding to get the most milk. This pattern of giving milk and being pregnant is called the lactation cycle.

For about 20 days after giving birth, the cow is called a "fresh cow." Milk production quickly increases during this time. The first milk, called colostrum, is very rich in fats, protein, and important immune cells from the mother. This colostrum is usually not sold. Instead, it is very important for the calf's early nutrition. It helps the calf get protection from diseases before its own immune system is fully developed.

The next 30 to 60 days of the lactation cycle are when milk production is highest. The amount of milk produced each day during this time varies a lot. It depends on the cow's breed, her health, her genes, and her food. During this period, the cow might use her body's stored energy to keep up high milk production. Her food intake will also increase. After this peak, the cow's milk production will slowly drop for the rest of the cycle. Farmers often breed the cow soon after she passes her peak production. For a while, the cow's food intake will stay high before also starting to drop. After peak milk production, her body condition will also slowly get better.

Farmers usually continue to milk the cow until she is about two months away from giving birth again. Then, they "dry her off." Giving the cow a break during the last part of her pregnancy allows her udder to rest and get ready for the next calf. It also lets her body recover and helps the calf grow normally. If a cow's body condition is poor, she won't produce as much milk in the next cycle. A less healthy new calf will also affect the quality of future milking herds. There is also evidence that resting the udder during the dry period is important for keeping high milk production levels in later cycles.

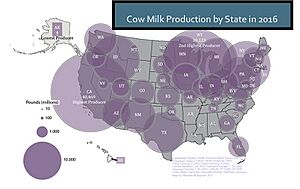

Dairy Farming in the United States

In the United States, the top five states for milk production are California, Wisconsin, New York, Idaho, and Texas. Dairy farming is also important in Florida, Minnesota, Ohio, and Vermont. There are about 40,000 dairy farms in the United States.

Pennsylvania has 8,500 farms with 555,000 dairy cows, producing about $1.5 billion in milk revenue each year.

Milk prices dropped in 2009. Some people were concerned about how large companies affected the milk market. In 2011, a judge approved a $30 million payment to 9,000 farmers in the Northeast.

The size of dairy herds in the U.S. varies. On the West Coast and Southwest, large farms are common, with about 1,200 cows. In the Midwest and Northeast, where land is limited, farms might have around 50 cows. The average farm in the U.S. has about 100 cows. However, nearly half of all cows live on farms with 1,000 or more cows.

Dairy Farming in the European Union

| Rank | Country | Production (106 kg/y) |

|---|---|---|

(all 27 countries) |

153,033 | |

| 1 | 28,691 | |

| 2 | 24,218 | |

| 3 | 13,237 | |

| 4 | 12,836 | |

| 5 | 12,467 | |

| 6 | 11,469 | |

| 7 | 7,252 | |

| 8 | 5,809 | |

| 9 | 5.373 | |

| 10 | 4,814 |

The table above shows the total milk production in European Union countries in 2009. Germany, France, and the United Kingdom were the top three milk producers in the EU that year.

See also

- Alfa Laval

- Animal husbandry

- Camel milk

- Dairy cattle

- Dairy products

- Factory farming

- Family farm

- List of dairy products

- Managed intensive grazing

- Ubre Blanca, a record milk-producing cow

- Veal

- Veganism

Images for kids

-

Holstein cows on a dairy farm, Comboyne, New South Wales

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |