Midwestern United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Midwestern United States

The Midwest, The Heartland, American Midwest

|

|

|---|---|

This map reflects the Midwestern United States as defined by the Census Bureau.

|

|

| Subregions | |

| Country | United States |

| States |

|

| Largest metropolitan areas |

|

| Largest cities | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 750,522 sq mi (1,943,840 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 68,985,454 |

| • Density | 91.91663/sq mi (35.489210/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Midwesterner |

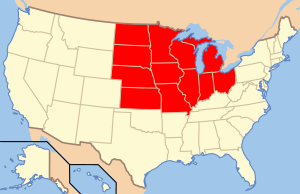

The Midwestern United States is a large region in the northern central part of the United States. It is also called the Midwest or the Heartland. The U.S. Census Bureau officially defines it as one of the four main regions of the country. It sits between the Northeastern United States and the Western United States. To the north is Canada, and to the south is the Southern United States.

The Midwest includes 12 states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. This area is mostly flat land, known as the Interior Plain. It is located between the Appalachian Mountains in the east and the Rocky Mountains in the west. Important rivers here include the Ohio River, the Upper Mississippi River, and the Missouri River. In 2020, over 68 million people lived in the Midwest.

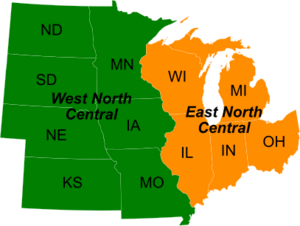

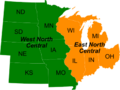

The Midwest is split into two parts by the Census Bureau. The East North Central States include Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin. These states are also part of the Great Lakes region. The West North Central States include Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota. Many of these are also part of the Great Plains.

Chicago is the biggest city in the Midwest. It is also the third largest city in the entire United States. The Chicago area, called Chicagoland, is home to 10 million people. Other big Midwestern cities are Columbus, Indianapolis, Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Omaha, Minneapolis, Cleveland, Cincinnati, St. Paul, and St. Louis.

The Midwest has a strong economy. It mixes big industries with farming. Large parts of the region are known as the Corn Belt. Here, lots of corn is grown. Other important parts of the economy include finance, medicine, and education. Because it's in the middle of the country, the Midwest is a major hub for transportation. Goods travel by river, train, truck, and plane.

Contents

History of the Midwest

Early Native American Cultures

Long ago, the Midwest was home to many Native American groups. The earliest people, called Paleo-Americans, lived in the Great Plains and Great Lakes areas around 12,000 BCE.

Later cultures included the Archaic period, the Woodland Tradition, and the Mississippian Period. The Mississippian people were mostly farmers. They grew corn, beans, and squash in the rich river floodplains. They also hunted and fished. These groups built large earth mounds. Their culture declined around 1400, possibly due to climate change.

Great Lakes Tribes

Major tribes in the Great Lakes region included the Huron, Ottawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Miami. Many of these tribes spoke Algonquian languages. They used stone, bone, and wood tools for hunting and farming. They also made canoes for fishing. Most lived in wigwams, which were easy to move.

Some tribes, like the Ojibwe, focused on hunting and fishing. Others, like the Sac and Miami, both hunted and farmed. They had trade networks that reached far across North America. Tribes had different ways of organizing their communities and different religious beliefs. For example, the Hurons believed in Yoscaha, a spirit who created the world. The Ojibwe believed in the Great Spirit.

Great Plains Tribes

The Plains Indians lived on the wide plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains. They are famous for their horse culture and their conflicts with settlers.

Plains Indians are often divided into two groups. The first group were nomads who followed large herds of buffalo. They included the Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Lakota. The second group were semi-settled tribes. They hunted buffalo but also lived in villages and grew crops. These included the Arikara, Mandan, and Pawnee.

Buffalo were the main food source for nomadic tribes. They used every part of the buffalo for food, clothing, tools, and shelter. Tribes lived in teepees because they were easy to move. When Spanish horses arrived in the 18th century, tribes quickly started using them. Horses made hunting and travel much easier.

The Dakota or Sioux were one of the most powerful tribes. They controlled a large area in the Great Plains. They were a major challenge to American expansion. Today, the Sioux live on reservations in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Minnesota, Montana, and parts of Canada.

European Exploration and Settlement

European settlement in the Midwest began in the 1600s. French explorers came to the region, which became known as New France. This included the Illinois Country.

Mapping the Mississippi River

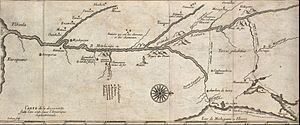

In 1673, the Governor of New France sent Jacques Marquette, a priest, and Louis Jolliet, a fur trader, to explore. They traveled through the Great Lakes and entered the Mississippi River. They were the first to map the northern part of the Mississippi. They found that it was easy to travel by water from the St. Lawrence River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. They also noted that the Native people were generally friendly and the land had many resources. French officials then set up a network of fur trading posts.

Fur Trade

The fur trade was very important in early European and Native American relations. Europeans traded guns, clothing, blankets, and other goods for furs.

The French and Native Americans often saw their trade as an exchange of gifts. This helped build friendships and alliances. French traders sometimes married Native American women. These women were important because they helped process the animal furs.

British traders also entered the fur trade. They often offered better goods and prices than the French. This created competition between the French and British. After Britain won the Seven Years' War, they took control of New France. The British tried to change the trade system, which led to conflicts like Pontiac's War. Eventually, they had to go back to a system more like the French one.

American Settlement and Growth

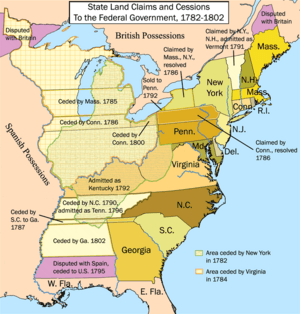

After the French left in 1763, many French settlers stayed in small villages along the Mississippi River. The United States gained control of the area east of the Mississippi. In 1803, the U.S. bought the land west of the Mississippi in the Louisiana Purchase.

American settlers began moving into the Midwest. They traveled over the Appalachian Mountains or through the Great Lakes waterways. Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) became a main starting point for settlers. Large-scale settlement became possible after Native American tribes were defeated at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Many people also came north from Kentucky into southern Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

Early farmers grew corn and vegetables. They often cleared land, sold it, and then moved further west. The government tried to move Native Americans to western lands to make way for farmers.

Native American Conflicts

Conflicts between settlers and Native Americans continued. In 1791, U.S. forces were defeated by a group of tribes led by Miami Chief Little Turtle. This was the greatest defeat of a U.S. Army by Native Americans.

The War of 1812 also involved fighting in the Midwest. After the U.S. won key battles, the British stopped supporting their Native American allies in the region. This ended major Native American warfare east of the Mississippi River.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore the new Louisiana Purchase. They started in Illinois and traveled along the Missouri River. Their goal was to map the land, find trade routes, and establish U.S. authority over Native peoples. They met many different tribes and returned in 1806.

Politics and Social Change

The Midwest has played a big role in American politics. From 1860 to 1920, both major political parties often chose their presidential candidates from this region.

The Republican Party started in the Midwest in the 1850s. Its members included many people from New England who had moved to the upper Midwest. The party was against the spread of slavery.

American Civil War

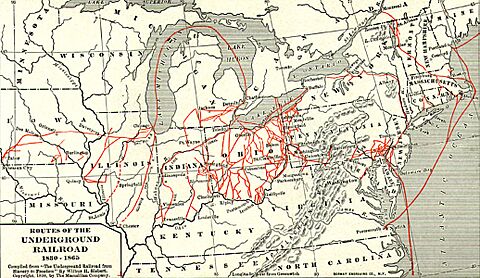

The Midwest was central to the fight over slavery. The Northwest Ordinance region, which is the heart of the Midwest, was the first large area in the U.S. to ban slavery. The Ohio River formed a boundary between free and slave states.

The Midwest, especially Ohio, was a main route for the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom in Canada. Between 1850 and 1860, about 100,000 enslaved people escaped using this route. The Underground Railroad used meeting points, secret routes, and safe houses provided by people who were against slavery.

The first violent conflicts leading to the American Civil War happened in Kansas and Missouri. This period was called "Bleeding Kansas" (1854-1858). The main question was whether Kansas would become a free state or a slave state. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed settlers to decide this through popular vote. This led to people from both sides moving to Kansas, causing fights. Kansas joined the Union as a free state in 1861, just before the Civil War began.

Immigration and Industry

After the Civil War, many European immigrants came directly to the Midwest. German immigrants settled in Ohio, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and other states. Irish immigrants went to cities like Cleveland and Chicago. People from Scandinavia, Poland, and Hungary also settled in Midwestern cities and farms.

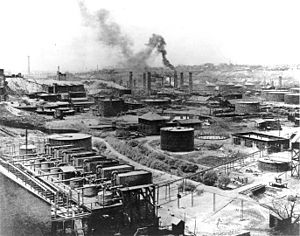

The late 1800s saw a rise in industrialization and urbanization. The Great Lakes states became a center for industry and new ideas. Factories and businesses grew, attracting people from rural areas and other countries. John D. Rockefeller started his Standard Oil Company in Cleveland. Many large companies began in the Great Lakes region.

In the 20th century, many African Americans moved from the Southern United States to Midwestern cities. This was called the Great Migration. They sought new job opportunities and to escape unfair treatment. This changed the populations of cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Detroit.

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era was a time of social and political reform. It aimed to fix problems caused by industrial growth. Jane Addams started Hull House in Chicago in 1889. This was a settlement house that helped new immigrants. It provided social services and helped immigrants become citizens.

Midwestern mayors like Hazen S. Pingree and Tom L. Johnson led early reforms against corrupt city politics. Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin was a famous leader of Midwestern progressivism. He pushed for reforms like direct primary elections, fair campaign funding, and child labor laws. These reforms became a model for other states.

Geography of the Midwest

The Midwest is mostly flat or gently rolling land. This makes it great for farming. Most of the eastern part is called the Interior Lowlands. These lands slowly rise to the west, forming the Great Plains. Most of the Great Plains is now used for farming.

While much of the region is flat, there are some varied areas. These include:

- The eastern Midwest near the Appalachian Mountains.

- The Great Lakes Basin.

- The rugged uplands of northern Minnesota, part of the Canadian Shield.

- The Ozark Mountains in southern Missouri.

- The Driftless Area in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Illinois, which was not covered by glaciers.

As you go west, the land becomes flatter. Prairies cover most of the Great Plains states. The amount of rainfall decreases from east to west. This leads to different types of prairies:

- Tallgrass prairie in the wetter east.

- Mixed-grass prairie in the central Great Plains.

- Shortgrass prairie closer to the Rocky Mountains.

Today, these prairie types match the areas where corn/soybeans, wheat, and rangelands are found. Much of the original forests in the Upper Midwest were cut down in the late 1800s. Now, most of the Midwest is either urban areas or farmland.

What Defines the Midwest?

The term Midwest started being used in the late 1800s. It first referred to Kansas and Nebraska as the "civilized" parts of the West.

The U.S. Census Bureau defines the Midwest as these 12 states:

- Illinois: Old Northwest, Mississippi River, Ohio River, and Great Lakes state.

- Indiana: Old Northwest, Ohio River, and Great Lakes state.

- Iowa: Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River, and Missouri River state.

- Kansas: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state.

- Michigan: Old Northwest and Great Lakes state.

- Minnesota: Old Northwest, Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River, and Great Lakes state.

- Missouri: Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River, Missouri River, and border state.

- Nebraska: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state.

- North Dakota: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state.

- Ohio: Old Northwest, Ohio River, and Great Lakes state.

- South Dakota: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state.

- Wisconsin: Old Northwest, Mississippi River, and Great Lakes state.

Other groups might define the Midwest slightly differently. For example, the National Park Service includes Arkansas in its Midwest Region.

Major Cities and Their Populations

The Midwest has many large cities and metropolitan areas. Here are the largest ones:

| Rank (Midwest) |

Rank (USA) |

MSA | Population | State(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | Chicago | 9,449,351 | Illinois Indiana Wisconsin |

|

| 2 | 14 | Detroit | 4,392,041 | Michigan |  |

| 3 | 16 | Twin Cities (Minneapolis–Saint Paul) | 3,690,261 | Minnesota Wisconsin |

|

| 4 | 21 | St. Louis | 2,820,253 | Missouri Illinois |

|

| 5 | 30 | Cincinnati | 2,249,797 | Ohio Kentucky Indiana |

|

| 6 | 31 | Kansas City | 2,192,035 | Missouri Kansas |

|

| 7 | 32 | Cleveland | 2,185,825 | Ohio |  |

| 8 | 33 | Columbus | 2,138,926 | Ohio |  |

| 9 | 34 | Indianapolis | 2,089,653 | Indiana |  |

| 10 | 40 | Milwaukee | 1,574,731 | Wisconsin |  |

| 11 | 51 | Grand Rapids | 1,150,015 | Michigan |  |

| 12 | 57 | Omaha | 967,604 | Nebraska Iowa |

|

| 13 | 74 | Dayton | 814,049 | Ohio |  |

| 14 | 81 | Des Moines | 709,466 | Iowa |  |

| 15 | 85 | Akron | 702,219 | Ohio |  |

| 16 | 87 | Madison | 680,796 | Wisconsin |  |

| 17 | 90 | Wichita | 647,610 | Kansas |  |

| 18 | 96 | Toledo | 606,240 | Ohio |  |

People and Culture

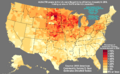

The Midwest is home to many different groups of people. According to a 2022 survey, most people in the Midwest are of German ancestry (22.6%). Other large groups include those of Irish (10.6%) and English (9.4%) ancestry. The Midwest has the largest number of German-Americans in the U.S. In states like North Dakota and Minnesota, many people have Scandinavian roots.

Historically, the Midwest had few Black residents. But during the Great Migration in the 20th century, many African Americans moved from the South to Midwestern cities. They sought better jobs and to escape unfair treatment. This led to big changes in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland. Today, Black Americans make up about 10% of the Midwest's population, mostly in urban areas. Most rural areas in the Midwest are still mainly White.

Illinois is the most diverse state in the Midwest. It is also considered one of the most representative states for the overall population of the United States.

The average household income in the Midwest is a little lower than the national average. About 12.2% of people in the region live below the poverty line. The average age in the Midwest is 39.2 years, which is similar to the rest of the U.S.

Religion in the Midwest

Like most of the United States, the Midwest is mainly Christian. Most Midwesterners are Protestants. The Catholic Church is the largest single Christian group. Lutherans are common in the Upper Midwest, especially in states with many German and Scandinavian people.

Other religions like Judaism and Islam are practiced by a smaller part of the population. These groups are mostly found in big cities. Many Midwesterners attend religious services regularly.

Midwestern Accents

The way people speak in the Midwest is generally different from the South or the Northeast. The accent in most of the Midwest is often considered "standard" American English. This is the accent often used by national TV and radio hosts.

However, some areas have unique accents. In the Great Lakes region, some cities are experiencing the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which changes how vowels are pronounced. The dialect in Minnesota, western Wisconsin, and parts of North Dakota has influences from Scandinavia and Canada. Missouri has a mix of different accents, including some Southern influences in its southern parts.

Music of the Midwest

German immigrants helped establish musical traditions like choral and orchestral music. The polka also became popular due to Czech and German influences.

In the 20th century, many Southerners moved to Midwestern cities. They brought jazz, blues, bluegrass, and rock and roll with them. Chicago became a hub for Chicago blues. Detroit became famous for the Motown Sound and techno music.

Rock and roll was first named a new music style in 1951 by Cleveland radio DJ Alan Freed. He helped make the term "rock and roll" popular. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is located in Cleveland because of his contributions. Chuck Berry from St. Louis also greatly influenced rock music.

Many famous musicians came from the Midwest. Motown artists like Aretha Franklin, the Supremes, and Stevie Wonder came from Detroit. In the 1970s and 80s, artists like Bob Seger and John Mellencamp created heartland rock, which focused on Midwestern working-class life. Prince developed the "Minneapolis sound." House Music, a type of electronic dance music, started in Chicago in the 1980s.

Sports in the Midwest

The Midwest is home to many professional sports teams in major leagues like the NFL, MLB, NBA, WNBA, NHL, and MLS.

- Chicago: Bears (NFL), Cubs, White Sox (MLB), Bulls (NBA), Sky (WNBA), Blackhawks (NHL), Fire FC (MLS), Stars (NWSL).

- Cincinnati: Bengals (NFL), Reds (MLB), FC Cincinnati (MLS).

- Cleveland: Browns (NFL), Guardians (MLB), Cavaliers (NBA).

- Columbus, Ohio|Columbus: Blue Jackets (NHL), Crew (MLS).

- Detroit: Lions (NFL), Tigers (MLB), Pistons (NBA), Red Wings (NHL).

- Green Bay, Wisconsin|Green Bay: Packers (NFL).

- Indianapolis: Colts (NFL), Pacers (NBA), Fever (WNBA).

- Kansas City: Chiefs (NFL), Royals (MLB), Sporting (MLS), Current (NWSL).

- Milwaukee: Brewers (MLB), Bucks (NBA).

- Minneapolis–Saint Paul: Vikings (NFL), Twins (MLB), Timberwolves (NBA), Lynx (WNBA), Wild (NHL), United (MLS).

- St. Louis: Cardinals (MLB), Blues (NHL), City SC (MLS).

Many Midwestern universities also have strong college sports teams, especially in the Big Ten Conference and Big 12 Conference. These include teams like the Michigan Wolverines, Ohio State Buckeyes, and Kansas Jayhawks.

The Midwest is also known for auto racing. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway hosts the famous Indianapolis 500-Mile Race every year.

Economy

Farming and Agriculture

Agriculture is a huge part of the Midwest's economy. The region has some of the best farming land in the world. Its fertile soil and the invention of the steel plow helped farmers grow huge amounts of grain. The Midwest is often called the nation's "breadbasket." It produces a lot of corn, wheat, soybeans, and oats.

In 1837, an Illinois blacksmith named John Deere created a steel plow. This plow could cut through the tough prairie soil, making it much easier to farm. Farms quickly spread across the region. The Midwest is now a global leader in corn and soybean production. Iowa and Illinois are the top two states for soybeans. Iowa also produces the most corn in the U.S.

Wheat is also grown throughout the Midwest. The U.S. is one of the top wheat producers in the world. Midwestern states also lead in other farm products like pork (Iowa), beef (Nebraska), dairy (Wisconsin), and chicken eggs (Iowa).

Finance and Business

Chicago is the biggest financial center in the Midwest. It has the third largest economy of any city area in North America. Chicago is home to major financial exchanges, like the CME Group, which includes the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade. These exchanges are important for trading things like corn, wheat, and other goods. Chicago also has the headquarters for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Other Midwestern cities also have important financial centers. For example, Cleveland, Kansas City, and Minneapolis also have Federal Reserve Banks. Many large insurance companies are based in the Midwest, such as Nationwide Insurance in Columbus, Ohio, and State Farm Insurance in Illinois.

Manufacturing

The Midwest has a long history of manufacturing. Its rivers and lakes helped transport goods easily. The region is a global leader in advanced manufacturing. Many important inventions and business ideas came from here. For example, John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil company in Cleveland set new ways for businesses to operate. Cyrus McCormick's Reaper led to big agricultural machinery companies in Chicago.

The Midwest is especially known for making cars. Henry Ford's assembly line changed how cars were made. The Detroit area became the world's center for car manufacturing. Factories across the region produce cars and car parts. Akron, Ohio became a leader in rubber production because of the demand for tires. Today, General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford Motor Company still have their main offices in the Detroit area.

Images for kids

-

Monks Mound, located at the Cahokia Mounds near Collinsville, Illinois, is the largest Precolumbian earthwork north of Mesoamerica and a World Heritage Site.

-

Winnebago family (1852)

-

Young Oglala Lakota girl in front of tipi with puppy beside her, probably on or near Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota

-

Cumulus clouds hover above a yellowish prairie at Badlands National Park, South Dakota, native lands to the Sioux.

-

The bell donated by King Louis XV in 1741 to the French mission at Kaskaskia, Illinois. It was later called the "Liberty Bell of the West", after it was rung to celebrate U.S. victory in the Revolution

-

The state cessions that eventually allowed for the creation of the territories north and southwest of the River Ohio

-

Northwest Territory 1787

-

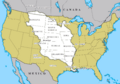

Louisiana Purchase 1803

-

The first local meeting of the new Republican Party took place at the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin on March 20, 1854.

-

Ohio River near Rome, Ohio

-

Lake Michigan is shared by Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Pictured is Indiana Dunes National Park in northwest Indiana.

-

Homesteaders in central Nebraska in 1888

-

Tragic Prelude, in the Kansas State Capitol

-

A map of various Underground Railroad routes

-

The first Standard Oil refinery was opened in Cleveland by businessman John D. Rockefeller.

-

Eugene V. Debs speaking in Canton, Ohio, in 1918, being arrested for sedition shortly thereafter.

-

The Upper Mississippi River viewed from Effigy Mounds National Monument, Iowa

-

Flint Hills grasslands of Kansas

-

Badlands of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

-

Divisions of the Midwest by the U.S. Census Bureau into East North Central and West North Central, separated largely by the Mississippi River

-

Scotts Bluff National Monument in western Nebraska

-

A pastoral farm scene near Traverse City, Michigan, with a classic American red barn

-

The Gary Works of Gary, Indiana is the largest integrated steel mill in North America.

-

The Milwaukee Art Museum is located on Lake Michigan.

-

Manasseh Cutler Hall, constructed by 1816, was the first academic building in the former Northwest Territory.

-

The University of Chicago is considered among the most prestigious universities in the US.

-

The Hitsville U.S.A. building in Detroit was the first headquarters and studio of Motown, which played an important role in the racial integration of popular music.

-

Downtown Kansas City looking over Union Station

-

The 2007 Indianapolis 500 at Indianapolis Motor Speedway

-

Mount Rushmore is located in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

See also

In Spanish: Medio Oeste de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Medio Oeste de los Estados Unidos para niños