Missouri River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Missouri River |

|

|---|---|

The Missouri River in Montana

|

|

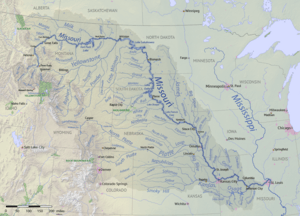

Map of the Missouri River and its tributaries in

North America |

|

| Other name(s) | Pekitanoui, Big Muddy, Mighty Mo, Wide Missouri, Kícpaarukstiʾ, Mnišoše |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri |

| Cities | Great Falls, MT, Bismarck, ND, Pierre, SD, Sioux City, IA, Omaha, NE, Brownville, NE, Saint Joseph, MO, Kansas City, KS, Kansas City, MO, St. Louis, MO |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Brower's Spring near Brower's Spring, Montana 9,100 ft (2,800 m) 44°33′02″N 111°28′21″W / 44.55056°N 111.47250°W |

| 2nd source | Firehole River–Madison River Madison Lake, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming 8,215 ft (2,504 m) 44°20′55″N 110°51′53″W / 44.34861°N 110.86472°W |

| River mouth | Mississippi River Spanish Lake, near St. Louis, Missouri 404 ft (123 m) 38°48′49″N 90°07′11″W / 38.81361°N 90.11972°W |

| Length | 2,341 mi (3,767 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 529,350 sq mi (1,371,000 km2) |

| Tributaries | |

| Type: | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

The Missouri River is a very long river in the United States. It starts in the Rocky Mountains in Montana. From there, it flows east and south for about 2,341 miles (3,767 km). Finally, it joins the Mississippi River north of St. Louis, Missouri. The Missouri River is the longest river in the United States.

The river's watershed covers a huge area. It is more than 500,000 square miles (1,300,000 km²). This area includes parts of ten U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Even though it's a tributary of the Mississippi, the Missouri River is a bit longer. It also carries a similar amount of water. Together with the lower Mississippi River, it forms the world's fourth-longest river system.

For over 12,000 years, people have relied on the Missouri River. It provided food and a way to travel. More than ten major groups of Native Americans lived in the watershed. Many of them were nomadic, meaning they moved around. They depended on the huge herds of bison (buffalo) that lived on the Great Plains. Europeans first saw the river in the late 1600s. The area then belonged to Spain and France. Later, it became part of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase.

The Missouri River was a key route for people moving west in the 1800s. The fur trade helped open up the region. Trappers explored the area and created trails. Many pioneers started moving west in the 1830s. They first used covered wagons. Later, more and more steamboats traveled on the river. Sometimes, there were conflicts between settlers and Native Americans. These conflicts led to some of the most difficult times in the American Indian Wars.

In the 1900s, people built many things along the Missouri River. They built systems for irrigation, to control floods, and to make hydroelectric power. Fifteen dams were built on the main river. Hundreds more were built on its smaller rivers (tributaries). Parts of the river were straightened to make it easier for boats to travel. This made the river almost 200 miles (320 km) shorter. Today, the lower Missouri valley has many people and farms. But all this building has affected wildlife, fish, and water quality.

Contents

- How the Missouri River Flows

- Missouri River's Drainage Area

- Major Rivers Joining the Missouri

- How Much Water Flows in the Missouri?

- How the Missouri River Formed

- First People Along the Missouri

- Early European Explorers

- The American Frontier and the Missouri River

- Building Dams on the Missouri River

- Traveling on the Missouri River

- Ecology and Human Impact

- Fun Things to Do on the Missouri River

- Images for kids

- See also

How the Missouri River Flows

The Missouri River starts in the Rocky Mountains. Three streams come together to form its beginning.

- The longest stream starts near Brower's Spring in Montana. It is about 9,100 feet (2,774 meters) above sea level. This stream flows into the Jefferson River.

- The Firehole River starts in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. It joins another river to form the Madison River.

- The Gallatin River also flows out of Yellowstone National Park.

The Missouri River officially begins where the Jefferson and Madison rivers meet. This is near Three Forks, Montana, in Missouri Headwaters State Park. The Gallatin River joins about a mile (1.6 km) downstream. The river then flows through Canyon Ferry Lake, a reservoir. After leaving the mountains, it flows northeast to Great Falls. Here, it drops over the Great Falls of the Missouri. This is a series of five big waterfalls.

The river then goes through a beautiful area of canyons and badlands. This area is called the Missouri Breaks. The Marias River joins from the west. Then, the river widens into the Fort Peck Lake reservoir. This is a few miles above where the Musselshell River joins. The river then passes through the Fort Peck Dam. Just below the dam, the Milk River joins from the north.

Flowing east through Montana, the Missouri receives the Poplar River. Then it crosses into North Dakota. Here, the Yellowstone River joins from the southwest. The Yellowstone is the biggest tributary by water volume. At this point, the Yellowstone actually carries more water than the Missouri.

The Missouri then curves east past Williston. It flows into Lake Sakakawea. This lake is formed by Garrison Dam. Below the dam, the Missouri receives the Knife River from the west. It flows south to Bismarck, North Dakota's capital. Here, the Heart River joins from the west. The river then slows into the Lake Oahe reservoir. This is just before the Cannonball River joins. As it continues south to Oahe Dam in South Dakota, the Grand, Moreau, and Cheyenne Rivers all join from the west.

The Missouri then turns southeast. It winds through the Great Plains. The Niobrara River and many smaller rivers join from the southwest. It then forms the border between South Dakota and Nebraska. The James River joins from the north. At Sioux City, the Big Sioux River comes in from the north. After this, the Missouri forms the Iowa–Nebraska border. It flows south to Omaha. Here, it receives its longest tributary, the Platte River, from the west. Further downstream, it forms the border between Nebraska and Missouri. Then it flows between Missouri and Kansas. The Missouri turns east at Kansas City. Here, the Kansas River enters from the west. It continues into north-central Missouri. East of Kansas City, the Grand River joins from the left. It passes south of Columbia. The Osage and Gasconade Rivers join from the south, downstream of Jefferson City. The river then goes around the north side of St. Louis. It joins the Mississippi River on the border between Missouri and Illinois.

Missouri River's Drainage Area

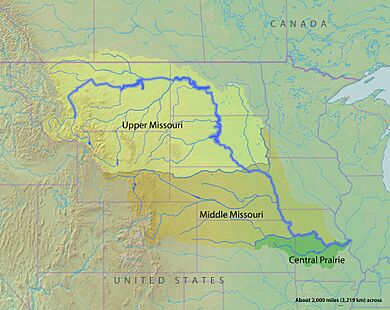

The Missouri River's drainage basin is huge. It covers about 529,350 square miles (1,371,000 km²). This is almost one-sixth of the United States. It's like the size of the Canadian province of Quebec. This area includes most of the central Great Plains. It stretches from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Mississippi River Valley in the east. It goes from southern Canada down to the border of the Arkansas River watershed.

The Missouri River is twice as long as the Mississippi River above where they meet. It also drains an area three times larger. The Missouri provides 45 percent of the water that flows into the Mississippi past St. Louis. During droughts, it can provide as much as 70 percent.

In 1990, about 12 million people lived in the Missouri River watershed. This included all of Nebraska. It also included parts of Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming. Small parts of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan are also in the watershed. The biggest city in the watershed is Denver, Colorado. It has over six hundred thousand people. Other big cities include Omaha, Nebraska, and Kansas City, Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas. The St. Louis area is also important. The northwestern part of the watershed has very few people.

The Missouri River watershed has a lot of farmland. Over 170,000 square miles (440,000 km²) are used for farming. This is about one-fourth of all farmland in the United States. It produces more than a third of the country's wheat, flax, barley, and oats. However, only 11,000 square miles (28,000 km²) of farmland in the basin are irrigated. Another 281,000 square miles (728,000 km²) are used for raising livestock, mostly cattle. Forested areas cover about 43,700 square miles (113,000 km²). Most of these are second-growth forests. Cities and towns cover less than 13,000 square miles (34,000 km²). Most developed areas are along the main river and its major tributaries. These include the Platte and Yellowstone Rivers.

The height of the land in the watershed changes a lot. It goes from just over 400 feet (122 meters) at the Missouri's mouth. It rises to 14,293 feet (4,357 meters) at Mount Lincoln in Colorado. The river drops 8,626 feet (2,629 meters) from its source at Brower's Spring. The plains in the watershed are mostly flat. But the land rises about 10 feet per mile (1.9 m/km) from east to west. The eastern border of the watershed is less than 500 feet (152 meters high). But at the base of the Rockies, many places are over 3,000 feet (914 meters) above sea level.

The Missouri's drainage basin has changing weather and rainfall. It has a continental climate. This means warm, wet summers and harsh, cold winters. Most of the watershed gets 8 to 10 inches (200 to 250 mm) of rain each year. But the western Rockies and southeastern Missouri can get up to 40 inches (1,000 mm). Most rain falls in summer in the lower and middle basin. The upper basin has strong but short summer thunderstorms. Winter temperatures in the north and west often drop to -20°F (-29°C) or lower. They can even reach -60°F (-51°C). Summer highs can go over 100°F (38°C) in most areas.

Major Rivers Joining the Missouri

Over 95 important rivers and hundreds of smaller ones flow into the Missouri River. Most of the larger ones join closer to the Missouri's mouth. Most rivers in the Missouri River basin flow from west to east. This follows the slope of the Great Plains. However, some eastern rivers like the James, Big Sioux, and Grand River flow from north to south.

The biggest rivers joining the Missouri by water flow are the Yellowstone in Montana and Wyoming. Also, the Platte in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska. And the Kansas–Republican/Smoky Hill and Osage in Kansas and Missouri. Each of these rivers drains an area larger than 50,000 square miles (130,000 km²). Or they have an average water flow greater than 5,000 cubic feet per second (140 m³/s). The Yellowstone River has the highest water flow. This is true even though the Platte is longer and drains a larger area. The Yellowstone's flow is about 13,800 cubic feet per second (391 m³/s). This is 16 percent of all the water in the Missouri basin. It is almost double the flow of the Platte.

The table below lists the ten longest rivers that flow into the Missouri. It also shows their drainage areas and water flows. The length is measured to the very start of the river, no matter its name. For example, the main part of the Kansas River is 148 miles (238 km) long. But if you include its longest starting rivers, the Republican River (453 miles/729 km) and the Arikaree River (156 miles/251 km), the total length is 749 miles (1,205 km). Similar things happen with the Platte River. Its longest starting river, the North Platte River, is more than twice as long as the main Platte River.

The Missouri's starting rivers above Three Forks go much further upstream than the main river. If measured to the farthest source at Brower's Spring, the Jefferson River is 298 miles (480 km) long. So, measured to its highest starting point, the Missouri River is 2,639 miles (4,247 km) long. When combined with the lower Mississippi, the Missouri and its starting rivers form part of the world's fourth-longest river system, at 3,745 miles (6,027 km).

| Longest tributaries of the Missouri River | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Length | Watershed | Discharge | |||

| mi | km | mi2 | km2 | ft3/s | m3/s | |

| Platte River | 1,061 | 1,708 | 84,910 | 219,900 | 7,037 | 199 |

| Kansas River | 749 | 1,205 | 59,500 | 154,000 | 7,367 | 209 |

| Milk River | 729 | 1,170 | 15,300 | 39,600 | 618 | 17.5 |

| James River | 710 | 1,140 | 21,500 | 55,700 | 646 | 18.3 |

| Yellowstone River | 702 | 1,130 | 70,000 | 180,000 | 13,800 | 391 |

| White River | 580 | 933 | 10,200 | 26,420 | 570 | 16.1 |

| Niobrara River | 568 | 914 | 13,900 | 36,000 | 1,720 | 48.7 |

| Little Missouri River | 560 | 900 | 9,550 | 24,700 | 533 | 15.1 |

| Osage River | 493 | 793 | 14,800 | 38,300 | 11,980 | 339 |

| Big Sioux River | 419 | 674 | 8,030 | 20,800 | 1,320 | 37.4 |

How Much Water Flows in the Missouri?

The Missouri River is the ninth largest river in the United States by how much water it carries. Because the Missouri drains mostly dry areas, its water flow is lower and changes more than other long rivers in North America. Before dams were built, the river flooded twice a year. Once in spring from melting snow on the plains. And again in June from melting snow and summer rains in the Rocky Mountains. The June floods were much bigger. The river could carry ten times its normal amount of water in some years.

Over 17,000 reservoirs (man-made lakes) affect the Missouri's water flow. These reservoirs can hold a lot of water. They help control floods by reducing high water flows. They also increase low water flows. Water evaporating from these reservoirs makes the river's flow much smaller.

The United States Geological Survey measures the river's flow at 51 places. At Bismarck, North Dakota, the river's average flow is 21,920 cubic feet per second (621 m³/s). This is from 35% of the total river basin. At Kansas City, the average flow is 55,400 cubic feet per second (1,570 m³/s). This is from about 91% of the entire basin.

The lowest measuring station with a long history is at Hermann, Missouri. Here, the average yearly flow was 87,520 cubic feet per second (2,478 m³/s) from 1897 to 2010. The highest average flow was in 1993. The lowest was in 2006. The biggest flow ever recorded was over 750,000 cubic feet per second (21,000 m³/s) on July 31, 1993. This was during a huge flood. The lowest flow was only 602 cubic feet per second (17.1 m³/s). This happened on December 23, 1963, because of an ice dam.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How the Missouri River Formed

The Rocky Mountains, where the Missouri River starts, formed a long time ago. This happened during a period of mountain building called the Laramide Orogeny. It occurred about 70 to 45 million years ago. This event lifted up rocks and created the mountains. These mountains are important because snow and ice melting from them provide most of the water for the Missouri River.

The Missouri and many of its smaller rivers flow across the Great Plains. They cut into old layers of rock and soil. Before the Ice Age, the Missouri River was probably in three parts. One part flowed north to Hudson Bay. The other two parts flowed east. As the Earth got colder and the Ice Age began, glaciers changed the river's path. They pushed the Missouri River southeast. This made it connect into one single river system that flows across the land.

The Missouri River is nicknamed the "Big Muddy." This is because it carries a lot of sediment or silt. It used to carry about 175 to 320 million tons of sediment each year. But now, because of dams, it carries much less. Dams and channels keep the river from getting its natural sediment from its banks. Reservoirs along the Missouri trap about 36.4 million tons of sediment each year. Even with this, the river still carries more than half of the silt that goes into the Gulf of Mexico.

First People Along the Missouri

Evidence shows that people first lived in the Missouri River watershed about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. This was at the end of the last Ice Age. During this time, many people were moving across the land. The Missouri River was one of their main paths. Many groups settled along the Missouri. They became the ancestors of the Native American peoples of the Great Plains.

Native Americans who lived along the Missouri River had plenty of food, water, and shelter. Many animals lived on the plains. Before they were hunted, animals like the buffalo provided meat, clothing, and other items. The river's floodplain also had many plants for food. There are no written records from these tribes from before Europeans arrived. But early European explorers wrote about them. Some major tribes along the Missouri River included the Otoe, Missouria, Omaha, Ponca, Brulé, Lakota, Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Assiniboine, Gros Ventres, and Blackfeet.

The Missouri River was used for trade and travel. The river and its tributaries often marked tribal borders. Most Native Americans in the region moved between summer and winter camps. A major center for trade was along the Missouri River in the Dakotas. Here, many Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara villages were built on bluffs and islands. These villages were home to thousands of people. They later became trading posts for early French and British explorers. When horses were introduced, Native American life changed a lot. Horses allowed them to travel further. This made hunting, communication, and trade easier.

Millions of American bison once roamed the plains of the Missouri River basin. These animals were very important to the ecosystem. Most Native American groups relied on bison for food. Their hides and bones were used for many household items. The bison also benefited from Native Americans burning grasslands. This cleared old growth and helped new grass grow. But after Europeans arrived, both bison and Native American populations quickly declined. Too much hunting by colonists wiped out bison east of the Mississippi River by 1833. In the Missouri basin, only a few hundred remained. Diseases brought by settlers, like smallpox, also greatly reduced Native American populations. Without their main food source, many Native Americans were forced onto reservations.

Early European Explorers

In May 1673, French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette traveled down the Wisconsin and Mississippi Rivers. They hoped to reach the Pacific Ocean. In late June, they became the first Europeans to find the Missouri River. Their journals said it was flooding. Jolliet wrote, "I never saw anything more terrifying." He described many trees in the muddy water. They called the river Pekitanoui or Pekistanoui. But they did not explore the Missouri beyond its mouth. They later learned the Mississippi flowed to the Gulf of Mexico, not the Pacific.

In 1682, France claimed land west of the Mississippi River. This included the lower part of the Missouri. But the Missouri itself was not fully explored until 1714. Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont led an expedition that reached at least the Platte River. He wrote about the blond-haired Mandan people. So he likely reached their villages in North Dakota. Later that year, Bourgmont published a document called The Route To Be Taken To Ascend The Missouri River. This was the first time the name "Missouri River" was used. Many names he gave to smaller rivers are still used today.

Bourgmont had been in trouble with French authorities. But his reputation improved in 1720. The Pawnee, whom Bourgmont had befriended, attacked the Spanish Villasur expedition. This happened near Columbus, Nebraska, on the Missouri River. This stopped Spain from trying to take over French Louisiana for a while.

Bourgmont built Fort Orleans in 1723. This was the first European settlement on the Missouri River. It was near Brunswick, Missouri. In 1725, Bourgmont brought chiefs from several Missouri River tribes to visit France. He was given a special honor. Fort Orleans was later abandoned or attacked in 1726.

The French and Indian War started in 1754. France and Great Britain fought over land in North America. France lost the war in 1763. In the Treaty of Paris, France gave its Canadian lands to the British. In return, it got Louisiana from Spain. Spain initially let French traders continue their work on the Missouri. But this changed when British traders from the Hudson's Bay Company were found in the upper Missouri. In 1795, Spain offered a reward for the first person to reach the Pacific Ocean via the Missouri. But expeditions failed to reach far north.

James MacKay and John Evans had the most success. They built Fort Charles near Sioux City in 1795. At the Mandan villages, they removed British traders. They also found the location of the Yellowstone River. MacKay and Evans did not reach the Pacific. But they made the first accurate map of the upper Missouri River.

In 1795, the United States and Spain signed a treaty. It allowed Americans to use the Mississippi River and New Orleans. But three years later, Spain took back this right. In 1800, Spain secretly gave Louisiana back to Napoleon's France. Spain still managed the territory. In 1801, Spain gave the U.S. rights to the Mississippi and New Orleans again.

President Thomas Jefferson worried about losing access again. He offered to buy New Orleans from France. Instead, Napoleon offered to sell all of Louisiana for $15 million. This was less than 3 cents per acre. The deal was signed in 1803. It doubled the size of the United States.

In 1803, Jefferson asked Meriwether Lewis to explore the Missouri. He wanted Lewis to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean. People thought the Missouri and Columbia Rivers might be connected. Spain did not like the U.S. takeover. Spanish officials warned Lewis not to go. They also tried to stop him from seeing MacKay and Evans' map. But Lewis found a way to get it.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark started their famous journey in 1804. They had 33 people and three boats. They were the first Europeans to travel the entire Missouri and reach the Pacific Ocean. But they did not find a Northwest Passage. The maps they made were very helpful for future explorers. They also met many Native American tribes. They wrote detailed reports about the area's climate, plants, animals, and rocks. Many names of places in the upper Missouri basin today came from their expedition.

The American Frontier and the Missouri River

Fur Trading on the River

In the 1700s, fur trappers came to the northern Missouri River basin. They were looking for beaver and river otter. Their furs were very valuable in the North American fur trade. These trappers came from Canada, the Pacific Northwest, and the U.S. Midwest. Most did not stay long because they didn't find many animals.

In 1806, Lewis and Clark returned with exciting news. Their journals described lands full of buffalo, beaver, and river otter. In 1807, explorer Manuel Lisa organized a trip. This led to a huge growth in the fur trade in the upper Missouri River country. Lisa and his team traveled up the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers. They traded goods for furs with Native American tribes. They built a fort at the Yellowstone and Bighorn rivers. This business started small but grew quickly.

Lisa's men built Fort Raymond in 1807. It was a trading post for furs with Native Americans. This was different from the Pacific Northwest fur trade. There, companies like Hudson's Bay hired trappers. Fort Raymond was later replaced by Fort Lisa in North Dakota. Another Fort Lisa was built downstream in Nebraska. In 1809, the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company was started by Lisa, William Clark, and others. In 1828, the American Fur Company built Fort Union. It became the main center for the fur trade in the upper Missouri basin.

Fur trapping happened across the Rocky Mountains in the early 1800s. Trappers from many companies worked on thousands of streams. These included the Missouri, Columbia, Colorado, Arkansas, and Saskatchewan river systems. During this time, these trappers, called mountain men, created trails. These trails were later used by pioneers and settlers moving west. Transporting thousands of beaver pelts needed boats. This was one of the first big reasons for river transport on the Missouri.

By the late 1830s, the fur trade began to decline. Silk became popular instead of beaver fur. Also, the beaver population was greatly reduced by too much hunting. Native American attacks on trading posts also made it dangerous. The fur trade mostly ended in the Great Plains around 1850. But its legacy opened up the American West. Many settlers, farmers, and adventurers came to the area.

Settlers and Pioneers Move West

The Missouri River largely marked the American frontier in the 1800s. Especially downstream from Kansas City, where it turns east into Missouri. This area was called the Boonslick. It was first settled by Europeans, many of whom owned slaves. The major trails to the American West all started on the river. These included the California, Mormon, Oregon, and Santa Fe trails. The first part of the Pony Express involved a ferry across the Missouri at St. Joseph, Missouri. Most people traveling west by train also crossed the Missouri by ferry. This was between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha. The Hannibal Bridge was the first bridge to cross the Missouri River in 1869. Its location helped Kansas City become the largest city on the river upstream from St. Louis.

Over 500,000 people left the river town of Independence, Missouri, between the 1830s and 1860s. They went to different places in the American West. They had many reasons to go, like economic problems or gold discoveries. For most, the route went up the Missouri to Omaha, Nebraska. From there, they traveled along the Platte River. The Platte flows from the Rocky Mountains through the Great Plains. Early explorers found the Platte impossible to navigate by boat. One explorer said the Platte was "too thick to drink, too thin to plow." But the Platte provided plenty of water for pioneers. Covered wagons were the main way to travel until regular boat service started in the 1850s.

In the 1860s, gold was found in Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah. This brought another wave of people. Most goods and people traveled by boat on the Missouri and Kansas Rivers. It took 150 days to travel upstream by boat to Montana. A route west into Colorado followed the Kansas River and its tributaries to near Denver. The gold rushes led to many people settling in the Rocky Mountains.

As settlers moved onto the Great Plains, they had land conflicts with Native American tribes. This led to many fights and battles. The government made treaties with the Plains tribes. These treaties set borders and reserved land for Native Americans. But like many other treaties, they were often broken. This led to big wars. Over 1,000 battles were fought between the U.S. military and Native Americans. Eventually, the tribes were forced onto reservations.

Conflicts over the Bozeman Trail led to Red Cloud's War. The Lakota and Cheyenne fought the U.S. Army. The Native Americans won this war. In 1868, the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed. It promised that the Black Hills and other areas would be for Native Americans. But American miners found gold in the Black Hills. Settlers moved onto the land, and Native Americans attacked them. U.S. troops were sent to protect the miners. The war ended with an American victory. The Black Hills were opened to settlement. Native Americans were moved to reservations.

Building Dams on the Missouri River

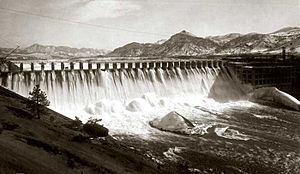

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many dams were built on the Missouri River. This changed 35 percent of the river into a series of reservoirs (lakes). Dams were built for several reasons. People needed electricity in the northwestern parts of the basin. Also, floods and droughts caused problems in growing cities and farms along the lower Missouri. Small, private dams for electricity existed since the 1890s. But the large dams for flood control were built in the 1950s.

Between 1890 and 1940, five dams were built near Great Falls. They made power from the Great Falls of the Missouri. Black Eagle Dam, built in 1891, was the first dam on the Missouri. The largest of these five dams, Ryan Dam, was built in 1913.

Other companies, like the Montana Power Company, also built dams. They developed the Missouri River above Great Falls for power. A small dam built in 1898 near Canyon Ferry Dam was the second dam on the Missouri. The steel Hauser Dam was finished in 1907. But it broke in 1908, causing huge floods downstream. Black Eagle Dam was partly blown up to save nearby factories. Hauser Dam was rebuilt in 1910 with concrete. It still stands today.

Holter Dam, about 45 miles (72 km) downstream of Helena, was the third hydroelectric dam. It was finished in 1918. Its reservoir flooded the Gates of the Mountains. Meriwether Lewis described this as "the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen." In 1949, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) began building the modern Canyon Ferry Dam. It was to control floods in the Great Falls area. By 1954, Canyon Ferry Lake covered the old 1898 dam.

[ The Missouri's temperament was as ] "uncertain as the actions of a jury or the state of a woman's mind".

— Sioux City Register, March 28, 1868

The Missouri basin had very bad floods around 1900. Especially in 1844, 1881, and 1926–1927. In 1940, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) finished Fort Peck Dam in Montana. This huge project created jobs during the Great Depression. It also helped control floods in the lower Missouri River. But Fort Peck only controls water from 11 percent of the Missouri River watershed. It had little effect on a big flood in 1943. This flood damaged factories in Omaha and Kansas City. It delayed military supplies during World War II.

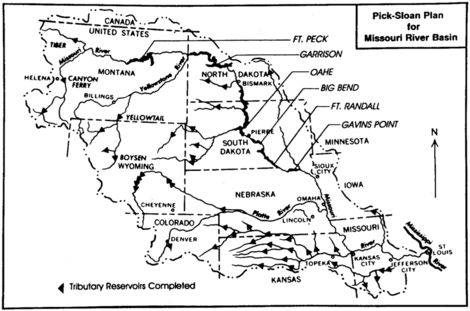

Because of flood damage, Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1944. This allowed the USACE to build many more dams on the Missouri. The 1944 act approved the Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program. This plan combined two ideas. The Pick plan focused on flood control and hydroelectric power. It called for large dams on the main Missouri River. The Sloan plan focused on irrigation. It included about 85 smaller dams on tributaries.

Early plans included a small dam in North Dakota and 27 smaller dams on the Yellowstone River. But people in the Yellowstone basin did not like this. So, the USBR suggested making the dam in North Dakota much bigger. This became Garrison Dam. This decision meant the Yellowstone is now the longest free-flowing river in the United States. In the 1950s, construction began on five main dams: Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall, and Gavins Point. These dams, along with Fort Peck, form the Missouri River Mainstem System.

Building these dams flooded Native American lands. This was especially true in the dry Dakotas, where fertile land was scarce. For example, 150,000 acres (61,000 ha) of land were taken from the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation for Garrison Dam. The tribes sued the government. They said the land could not be taken without their permission. After a long legal fight, the tribes were forced to accept a payment in 1947. They were also not allowed to use the reservoir shore for hunting or fishing.

The six dams of the Mainstem System are among the largest in the world by volume. Their reservoirs are also among the biggest in the U.S. They can hold over 74.1 million acre-feet (91.4 km³) of water. This is more than three years of the river's flow. This makes it the largest reservoir system in the United States. It also helps control floods. The power plants at these dams make about 9.3 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity each year. This is enough for many homes. Along with nearly 100 smaller dams on tributaries, the system provides water for irrigation to almost 7,500 square miles (19,000 km²) of land.

| Dams on the Missouri River | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dam | State(s) | Height | Reservoir | Capacity (Acre.ft) |

Capacity (MW) |

| Toston | MT | 56 ft (17 m) |

3,000 | 10 | |

| Canyon Ferry | MT | 225 ft (69 m) |

Canyon Ferry Lake | 1,973,000 | 50 |

| Hauser | MT | 80 ft (24 m) |

Hauser Lake | 98,000 | 19 |

| Holter | MT | 124 ft (38 m) |

Holter Lake | 243,000 | 48 |

| Black Eagle | MT | 13 ft (4.0 m) |

Long Pool | 2,000 | 21 |

| Rainbow | MT | 29 ft (8.8 m) |

1,000 | 36 | |

| Cochrane | MT | 59 ft (18 m) |

3,000 | 64 | |

| Ryan | MT | 61 ft (19 m) |

5,000 | 60 | |

| Morony | MT | 59 ft (18 m) |

3,000 | 48 | |

| Fort Peck | MT | 250 ft (76 m) |

Fort Peck Lake | 18,690,000 | 185 |

| Garrison | ND | 210 ft (64 m) |

Lake Sakakawea | 23,800,000 | 515 |

| Oahe | SD | 245 ft (75 m) |

Lake Oahe | 23,500,000 | 786 |

| Big Bend | SD | 95 ft (29 m) |

Lake Sharpe | 1,910,000 | 493 |

| Fort Randall | SD | 165 ft (50 m) |

Lake Francis Case | 5,700,000 | 320 |

| Gavins Point | NE SD |

74 ft (23 m) |

Lewis and Clark Lake | 492,000 | 132 |

| Total | 76,436,000 | 2,787 | |||

The table lists all fifteen dams on the Missouri River. Many of the dams on the upper Missouri (marked in yellow) create small lakes that may not have names. All dams are on the upper half of the river, above Sioux City. The lower river has no dams because it has been used for shipping for a long time.

Traveling on the Missouri River

[ Missouri River shipping ] "never achieved its expectations. Even under the very best of circumstances, it was never a huge industry".

— Richard Opper, former executive director

Missouri River Basin Association

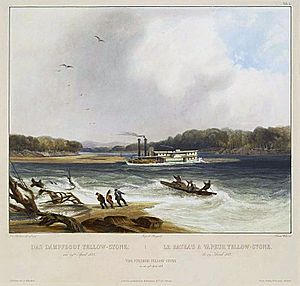

People have traveled on the Missouri River for thousands of years. Native Americans used canoes and bull boats. When Europeans came, they brought larger boats. The first steamboat on the Missouri was the Independence in 1819. By the 1830s, large boats carried mail and goods between Kansas City and St. Louis. Some even went further upstream. A few, like the Western Engineer and the Yellowstone, could reach eastern Montana.

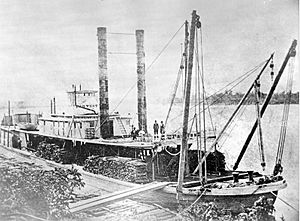

In the early 1800s, during the fur trade, steamboats and keelboats traveled almost the entire Missouri River. They carried beaver and buffalo furs. This led to the creation of the Missouri River mackinaw. These boats could only travel downstream. So, they were taken apart and sold for wood when they reached St. Louis.

Boat travel grew in the 1850s. Many boats carried pioneers, settlers, and miners. Most trips were from St. Louis or Independence to near Omaha. From there, people traveled overland along the Platte River. The Platte was wide but shallow and not good for boats. Steamboat navigation was busiest in 1858. Over 130 boats worked full-time on the Missouri. Side-wheeler steamboats were preferred. They were easier to steer than the larger sternwheelers used on the Mississippi.

But success did not mean safety. In the early days, before people controlled the river, its changing water levels and huge amounts of sediment caused many shipwrecks. About 300 vessels were wrecked. Because of the dangers, the average ship lasted only about four years. The building of railroads ended steamboat travel on the Missouri. Trains were faster and cheaper. By the 1890s, few boats were left. But transporting farm and mining products by barge saw a comeback in the early 1900s.

Since the 1900s, the Missouri River has been changed a lot for boat travel. About 32 percent of the river now flows through straight, man-made channels. In 1912, the USACE was told to keep the Missouri 6 feet (1.8 meters) deep. This was from Kansas City to the mouth, about 368 miles (592 km). They did this by building levees and wing dams. These structures direct the river's flow into a narrow channel. This prevents sediment from building up. In 1925, the USACE started to make the river's channel 200 feet (61 meters) wide. Two years later, they started digging a deep channel from Kansas City to Sioux City. These changes have made the river shorter. It was about 2,540 miles (4,088 km) long in the late 1800s. Now it is 2,341 miles (3,767 km).

Building dams on the Missouri under the Pick-Sloan Plan helped navigation. The large reservoirs of the Mainstem System provide a steady flow of water. This helps keep the navigation channel open all year. They can also stop most of the river's yearly floods. However, very high or low water levels, like droughts or big floods, are still hard for the dams to control.

In 1945, the USACE started a project to make the river's navigation channel 300 feet (91 meters) wide and 9 feet (2.7 meters) deep. This work continues today. The 735-mile (1,183 km) navigation channel from Sioux City to St. Louis is controlled by building rock dikes. These dikes direct the river's flow and remove sediment. They also cut off bends in the river and dig out the riverbed. But the Missouri has often resisted these efforts. In 2006, commercial barges got stuck because the channel was too shallow. The USACE was blamed for not keeping the channel deep enough.

In 1929, a group estimated that 15 million tons of goods could be shipped on the river each year. This led to the creation of the navigation channel. But shipping traffic has been much lower than expected. From 1994 to 2006, only about 683,000 tons of goods were shipped each year.

Missouri ships the most goods by far, accounting for 83 percent of river traffic. Kansas has 12 percent, Nebraska three percent, and Iowa two percent. Almost all barge traffic on the Missouri River carries sand and gravel. These materials are dug from the lower 500 miles (800 km) of the river. The rest of the shipping channel is rarely used by commercial boats.

For navigation, the Missouri River is split into two parts. The Upper Missouri River is north of Gavins Point Dam. This is the last dam on the river, just upstream from Sioux City, Iowa. The Lower Missouri River is the 840 miles (1,350 km) of river below Gavins Point until it meets the Mississippi. The Lower Missouri River has no dams or locks. But it has many wing dams. These dams stick out into the river. They direct the river's flow into a 200-foot (61 m) wide, 12-foot (3.7 m) deep channel. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built and maintains these wing dams. There are no plans to build locks on the Missouri River.

Why River Traffic Has Decreased

The amount of goods shipped by barges on the Missouri River has dropped a lot since the 1960s. In the 1960s, the USACE thought it would increase to 12 million tons per year by 2000. Instead, it went down. The amount of goods fell from 3.3 million tons in 1977 to just 1.3 million tons in 2000. One big drop was in farm products, especially wheat. One reason is that irrigated land along the Missouri has not been fully developed. In 2006, barges on the Missouri carried only 200,000 tons of products. This is equal to the daily freight traffic on the Mississippi.

Droughts in the early 2000s and competition from railroads are the main reasons for less river traffic. The USACE not keeping the navigation channel deep enough has also hurt the industry. People are trying to bring back shipping on the Missouri River. River transport is efficient and cheap for moving farm products. Also, other transportation routes are getting too crowded. Solutions like making the navigation channel wider and releasing more water from reservoirs are being considered.

Drought conditions improved in 2010. About 334,000 tons were shipped on the Missouri. This was the first big increase since 2000. However, floods in 2011 closed parts of the river. This stopped hopes for a better year.

The lower Missouri River has no locks and dams. But it has many wing dams that make it harder for barges to navigate. In contrast, the upper Mississippi has 29 locks and dams. It averaged 61.3 million tons of cargo each year from 2008 to 2011. Its locks are closed in the winter.

Ecology and Human Impact

Natural History of the Missouri River

In the past, the Missouri River's floodplain was home to many plants and animals. The variety of life generally increased as you went downstream. From the cold headwaters in Montana to the warmer, wetter climate of Missouri. Today, the river's riparian zone (area along the banks) has mostly cottonwoods, willows, and sycamores. There are also other trees like maple and ash. Trees are generally taller further from the riverbanks. This is because land next to the river can erode during floods. The Missouri has a lot of sediment. So, it does not support many small water animals. But the basin has about 300 types of birds and 150 types of fish. Some, like the pallid sturgeon, are endangered. The Missouri's water and riverside habitats also support mammals. These include minks, river otters, beavers, muskrats, and raccoons.

The World Wide Fund For Nature divides the Missouri River watershed into three freshwater areas. These are the Upper Missouri, Lower Missouri, and Central Prairie. The Upper Missouri is mostly in Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas. It has dry grasslands with few different kinds of plants and animals. This is because of the Ice Age glaciers. No unique species are found only here. Except for the Rocky Mountain headwaters, this part of the watershed gets little rain. The Middle Missouri area includes Colorado, Nebraska, and parts of other states. It gets more rain and has forests and grasslands. Plant life is more diverse here. It also has about twice as many animal species. The Central Prairie area is on the lower Missouri. It includes parts of Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. This region has the most diverse plants and animals. Thirteen types of crayfish are found only in the lower Missouri.

How People Have Changed the River

Since river trade and industry began in the 1800s, human activity has badly polluted the Missouri. Most of the river's natural floodplain is gone. It has been replaced by irrigated farmland. Building on the floodplain has put more people and buildings at risk of floods. Levees have been built along more than a third of the river. They keep floodwater in the channel. But this makes the water flow faster. It also increases peak flows downstream. Fertilizer runoff is a big problem. It causes high levels of nitrogen and other nutrients. This pollution also affects the upper Mississippi, Illinois, and Ohio Rivers. Low oxygen levels in rivers and the huge Gulf of Mexico dead zone are caused by high nutrient levels from the Missouri.

Making the lower Missouri narrower and deeper has hurt plants and animals. Many dams and bank projects have been built. They helped turn 300,000 acres (1,200 km²) of Missouri River floodplain into farmland. Controlling the river has reduced sediment flowing downstream. It has also destroyed important habitats for fish, birds, and amphibians. By the early 2000s, native species populations were declining. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service suggested restoring river habitats for endangered species.

The USACE started projects to restore the ecosystem along the lower Missouri River. Because the shipping channel is not used much, some levees and wing dams can be removed. This allows the river to restore its banks naturally. By 2001, 87,000 acres (350 km²) of riverside floodplain were being restored.

Restoration projects have moved some trapped sediments. This has raised concerns about more pollution downstream. A 2010 report looked at the role of sediment in the Missouri River. It suggested understanding how sediment moves. This would help improve water quality and protect endangered species.

Protected Sections of the River

Several parts of the Missouri River are protected. They are part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. These sections include areas from Fort Benton to Robinson Bridge. Also, from Gavins Point Dam to Ponca State Park. And from Fort Randall Dam to Lewis and Clark Lake. A total of 247 miles (398 km) of the river are protected. This includes 64 miles (103 km) of wild river and 26 miles (42 km) of scenic river in Montana. 157 miles (253 km) of the river are listed for recreation.

Fun Things to Do on the Missouri River

The six reservoirs of the Missouri River Mainstem System offer many fun activities. They have over 1,500 square miles (3,900 km²) of open water. The number of visitors has grown a lot. From 10 million visitor-hours in the mid-1960s to over 60 million in 1990. The government built boat ramps, campgrounds, and other public facilities. Recreational use of these reservoirs brings in $85–100 million to the local economy each year.

The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail is about 3,700 miles (5,950 km) long. It follows almost the entire Missouri River, from its mouth to its source. It traces the path of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The trail goes through eleven U.S. states. It passes through about 100 historic sites. These include the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

Parts of the river itself are set aside for recreation or preservation. The Missouri National Recreational River includes parts of the Missouri downstream from Fort Randall and Gavins Point Dams. These sections total 98 miles (158 km). They have islands, bends, sandbars, and other features. These features were once common but are now gone in other parts of the river. About 45 steamboat wrecks are found along these parts of the river.

Downstream from Great Falls, Montana, about 149 miles (240 km) of the river flow through rugged canyons. This area is called the Missouri Breaks. This part of the river is a U.S. National Wild and Scenic River. It is part of the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument. This preserve covers 375,000 acres (1,520 km²). It has steep cliffs, deep gorges, dry plains, and whitewater rapids. The preserve has many different plants and animals. Fun activities include boating, rafting, hiking, and watching wildlife.

In north-central Montana, about 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km²) along the Missouri River are part of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. This area centers on Fort Peck Lake. It is a natural northern Great Plains ecosystem. It has not been greatly changed by people, except for Fort Peck Dam. There are few marked trails. But the whole preserve is open for hiking and camping.

Many U.S. national parks are partly in the watershed. These include Glacier National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Badlands National Park. Parts of other rivers in the basin are also protected. For example, the Niobrara National Scenic River is a 76-mile (122 km) protected stretch of the Niobrara River. This is one of the Missouri's longest tributaries. The Missouri flows through or past many National Historic Landmarks. These include Three Forks of the Missouri, Fort Benton, Montana, Big Hidatsa Village Site, Fort Atkinson, Nebraska, and Arrow Rock Historic District.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Río Misuri para niños

In Spanish: Río Misuri para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |