Pallid sturgeon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pallid sturgeon |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scaphirhynchus albus | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Acipenseriformes |

| Family: | Acipenseridae |

| Genus: | Scaphirhynchus |

| Species: |

S. albus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Scaphirhynchus albus (S. A. Forbes & R. E. Richardson, 1905)

|

|

|

|

| Pallid sturgeon range | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Parascaphirhynchus albus S. A. Forbes and R. E. Richardson, 1905 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The pallid sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus albus) is a type of ray-finned fish that is in danger of disappearing. It lives only in the Missouri River and the lower Mississippi River in the United States.

This fish is named for its light, pale color. It is a close relative of the shovelnose sturgeon, which is more common. However, the pallid sturgeon is much bigger. It usually grows to be about 30 to 60 inches (76 to 152 cm) long and can weigh up to 85 pounds (39 kg) when it's fully grown.

Pallid sturgeon take a long time to grow up, about 15 years to become adults. They don't lay eggs very often, but they can live for a very long time, sometimes up to 100 years! This fish belongs to the sturgeon family, Acipenseridae. This family of fish has been around for about 70 million years, since the time of the dinosaurs. The pallid sturgeon hasn't changed much since then.

In 1990, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service added the pallid sturgeon to its list of endangered species. This was because very few young fish were seen, and overall sightings had dropped a lot. Now, it's rare to see them in the wild. It was the first fish in the Missouri River area to be listed as endangered. Scientists believe that losing their natural home is the main reason for their decline.

Most of the Missouri River has been changed by dams and channels. This has removed the gravel beds and slow-moving side channels that the sturgeon need to lay their eggs. Before the mid-1900s, pallid sturgeon were common. Anglers enjoyed catching such a large fish in fresh water. People also thought the fish tasted good, and its eggs were sometimes used for caviar.

Scientists and conservationists are working hard to save the pallid sturgeon. They are raising pallid sturgeon in about a dozen fish hatcheries. These young fish are released into the wild every year. To learn more about them, researchers put small radio transmitters inside some sturgeon. This helps them track the fish's movements and find places where they might lay eggs. Government agencies are also working together to improve the sturgeon's habitat by restoring spawning areas. This is very important for the species to survive in the wild.

Contents

About the Pallid Sturgeon

Naming and Family Tree

Scientists S. A. Forbes and R. E. Richardson officially named the pallid sturgeon in 1905. They put it in the genus Parascaphirhynchus and the family Acipenseridae. This family includes all sturgeon fish around the world.

The pallid sturgeon's closest relatives are the shovelnose sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus platorynchus), which is still quite common, and the Alabama sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus suttkusi), which is also very endangered. These three fish are part of a smaller group called Scaphirhynchinae. There's only one other group in this subfamily, Pseudoscaphirhynchus, which has three species found in parts of Asia.

The word "pallid" means "lacking color" or "pale." Compared to other sturgeon, the pallid sturgeon is indeed much lighter in color. Its scientific name, Scaphirhynchus albus, comes from Greek and Latin words. Scaphirhynchus means "spade snout," and albus is Latin for "white."

Understanding Their DNA

To help protect the pallid sturgeon, scientists have studied its DNA. They compare its DNA to that of other sturgeon species. This helps them understand how different groups of pallid sturgeon are related. It also shows how they differ from shovelnose sturgeon.

Early DNA studies once suggested that pallid and shovelnose sturgeon might be the same species. However, a study in 2000 looked at the DNA of pallid, shovelnose, and Alabama sturgeon. It showed that they are all separate species. Other studies from 2001 to 2006 looked at pallid sturgeon from different areas. They found that northern groups of pallid sturgeon are genetically different from those in the Atchafalaya River in Louisiana.

Scientists also study DNA to see how much pallid and shovelnose sturgeon hybridize, meaning they mix and create offspring together. More hybrids are found in southern populations than in northern ones. It's not known if these hybrid fish can have babies themselves. However, it seems that pallid sturgeon eggs are fertilized by male shovelnose sturgeon.

Physical Features

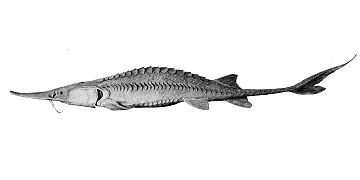

The pallid sturgeon is one of the biggest freshwater fish in North America. They usually measure between 30 and 60 inches (76 to 152 cm) long. They can weigh up to 85 pounds (39 kg). This species is very old and has looked almost the same for 70 million years. People have described its look as "primitive" or "dinosaur-like."

Even though they look similar, the shovelnose sturgeon is much smaller. It usually weighs no more than 5 pounds (2.3 kg). Pallid sturgeon are also much paler, with grayish-white backs and sides. Shovelnose sturgeon are brown. As pallid sturgeon get older, they become even whiter. Young pallid sturgeon can sometimes be mistaken for adult shovelnose sturgeon because their colors are similar. Both species have a heterocercal tail, meaning the top part of the tail fin is longer than the bottom part. This is more noticeable in pallid sturgeon.

Like other sturgeon, pallid sturgeon do not have scales or bones like most modern fish. Instead, they have a skeleton made of cartilage. They have five rows of thick cartilage plates along their sides, undersides, and backs. These plates are covered by skin and act like protective armor. Bony cartilage also runs along their back, from the dorsal fin to the tail.

The pallid sturgeon's snout and head are longer than those of the shovelnose sturgeon. Both species have mouths located far back from the tip of their snout. They don't have teeth. Instead, they use their mouths to suck up small fish, mollusks, and other food from the river bottom.

Both species also have four barbels that hang down from their snout near their mouth. These barbels are like feelers that help them find food. On pallid sturgeon, the two inner barbels are about half as long as the outer ones. On shovelnose sturgeon, all four barbels are the same length. The inner barbels of the pallid sturgeon are also positioned in front of the outer ones. For shovelnose sturgeon, all barbels are in a straight line. The length and position of these barbels are key ways to tell the two species apart.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Pallid sturgeon live a very long time, often more than 50 years, and possibly up to 100 years. Because they don't have bones or scales, it's hard to figure out their exact age. Like many animals that live a long time, pallid sturgeon become able to reproduce quite late in life. Males are ready to reproduce between 5 and 7 years old. Females are thought to be ready when they are at least 15 years old. One study found that females start developing eggs between 9 and 12 years old, but don't fully mature until 15.

They don't lay eggs every year. On average, they lay eggs every three years, but some studies suggest it could be as long as 10 years. Spawning usually happens from May to July.

Before dams were built on the Missouri River, pallid sturgeon would travel hundreds of miles upstream to lay eggs. They looked for rocky or hard surfaces to deposit hundreds of thousands of eggs. One female pallid sturgeon caught in the Missouri River was carrying an estimated 170,000 eggs! This was more than 11 percent of her total body weight.

After fertilization, pallid sturgeon eggs hatch in 5 to 8 days. The tiny larvae then drift downstream for several weeks. As the larvae grow tails, they look for slower-moving water. They slowly mature over about 12 years. Very few pallid sturgeon larvae survive to adulthood. Out of hundreds of thousands of eggs, only a few will live to become adult fish.

For many years, no natural reproduction of pallid sturgeon was seen. All the fish caught were older ones. But in the late 1990s, young pallid sturgeon were found in a restored river area of the lower Missouri River. This was the first time in 50 years that wild-spawned pallid sturgeon were documented. In 2007, two female pallid sturgeon were also reported to have laid eggs in the Missouri National Recreational River area. This area is downstream from the Gavins Point Dam on the Missouri River.

Where They Live and What They Need

Distribution of Pallid Sturgeon

Historically, the pallid sturgeon lived throughout the entire Missouri River and into the Mississippi River. They were probably rare or absent in the upper Mississippi because the habitat wasn't right for them. Today, the species is in danger across its whole range.

As of 2008, pallid sturgeon can still be found in their original areas. However, their numbers have dropped greatly since the mid-1900s. The Missouri and Mississippi rivers, from Montana to Louisiana, and the Atchafalaya River in Louisiana, still have an aging population of pallid sturgeon.

Pallid sturgeon have never been very common. Even in 1905, when they were first identified, they made up only one out of five sturgeon in the lower Missouri River. Where the Illinois River meets the Mississippi, they were as few as one in 500. Between 1985 and 2000, the ratio of pallid sturgeon to all sturgeon caught dropped even more. A 1996 study estimated that between 6,000 and 21,000 pallid sturgeon remained in the wild at that time.

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) studied six areas to estimate wild pallid sturgeon populations. These areas are called "recovery priority management areas" (RPMAs). In the northernmost area (RPMA 1) in Montana, only 45 wild fish remain. No young fish were seen, and the population was shrinking. In RPMA 2, also in Montana, only 136 wild fish remained. In RPMA 3, along the Missouri River, no native populations were found. All fish caught there seemed to be from hatcheries. However, these fish were growing well in that part of the river.

In RPMA 4, from Gavins Point Dam to where the Missouri and Mississippi rivers meet, at least 100 unique wild fish were found. There was also some evidence of wild reproduction here. In RPMA 5, between the Missouri/Mississippi meeting point and the Gulf of Mexico, several hundred fish were found. Again, there was some evidence of natural reproduction. The Atchafalaya River basin (RPMA 6) had similar findings to RPMAs 4 and 5, but with even more unique fish, totaling nearly 500.

What Kind of Habitat Do They Like?

Pallid sturgeon prefer rivers with moderate to fast currents. Most fish caught have been in rivers where the current moves between 0.33 and 2.9 feet per second (0.1 to 0.9 meters per second). They also like cloudy water and depths between 3 and 25 feet (0.9 to 7.6 meters). The species is more often found where there is a lot of sand on the river bottom, but they can also live in rocky areas. Pallid sturgeon prefer faster currents more than shovelnose sturgeon do.

A study in Montana and North Dakota tracked both pallid and shovelnose sturgeon using radio transmitters. Pallid sturgeon preferred wider river channels, sandbars in the middle of the river, and many islands. They were most often found in water depths between 2 and 47 feet (0.6 to 14.3 meters). The study also showed that pallid sturgeon could travel as much as 13 miles (21 km) per day. They could swim up to 5.7 miles per hour (9.2 km/h). Scientists believe pallid sturgeon preferred the muddy and warmer waters that were common before the Missouri River dams were built.

Saving the Pallid Sturgeon

Even though they were never thought to be very common, pallid sturgeon numbers dropped quickly in the late 1900s. The species was listed as endangered on September 6, 1990. The U.S. government and most states where pallid sturgeon live have started efforts to save them from extinction.

Wild reproduction of pallid sturgeon is rare or doesn't happen at all in most areas. This means people need to help them survive. Pallid sturgeon were once a prized fish for anglers. People enjoyed catching them, and the roe (eggs) from females were used for caviar. Now, all pallid sturgeon that are caught must be released back into the wild.

The Missouri River in states like North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Montana has been greatly changed. Dams and channels prevent fish from swimming upstream. The slower water flow and less sediment mean that the seasonal flooding of the floodplains no longer happens. Since the Fort Peck Dam was built in Montana in 1937, and with more damming and channeling, the Missouri River has lost over 90% of its wetlands and sandbar areas. More than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of the Missouri River have been changed. Only the part of the river above Fort Peck Reservoir in Montana remains mostly natural. These changes have harmed many native fish species.

In the 13 U.S. states where the pallid sturgeon lives, only a few other fish species are listed as endangered. Even with big efforts to save them, the fact that wild populations can't sustain themselves means the pallid sturgeon will likely need federal protection for many decades to come.

Efforts to Preserve the Species

Two groups of pallid sturgeon in the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Montana are at risk of disappearing. Scientists predict that wild pallid sturgeon in Montana could be gone by 2018. Even though a strong effort to stock fish began in 1996, it will take time to see results. This is because female pallid sturgeon don't start reproducing until they are about 15 years old.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation has been releasing large amounts of water from the Tiber Dam every four to five years. This is done to try and create a small "spring flood" effect. The goal is to restore and refresh the floodplains downstream. These water releases aim to create suitable homes for many fish species.

In Nebraska, a small number of pallid sturgeon have been caught in the lower parts of the Platte River. Unlike most rivers in the Mississippi-Missouri River System, the Platte River has only a few dams, and they are far upstream. The lower Platte River is shallow with many sandbars and small islands. Even though pallid sturgeon prefer deeper, more turbulent rivers, over a dozen pallid sturgeon have been caught in the Platte River between 1979 and 2003. Some of these were from hatcheries.

Many of these pallid sturgeon have been fitted with radio transmitters. These devices track their return to the Platte River when water levels and cloudiness are good. This usually happens in the spring and early summer. By midsummer, lower water levels and clearer water on the Platte River encourage the sturgeon to return to the Missouri River.

The lower Platte River, a stretch of more than 30 miles (48 km) from the Elkhorn River to where it meets the Missouri River, has good places for pallid sturgeon to lay eggs. However, there's no clear proof that spawning is happening there. Along with the lower Yellowstone River, the lower Platte River is considered one of the best remaining areas for natural spawning.

In Missouri, at the Lisbon Bottoms section of the Big Muddy National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, wild pallid sturgeon larvae were found in 1998. These young fish, not from hatcheries, were the first found in the lower Missouri River in 50 years. They were found in a side channel of the Missouri River that was created to provide good habitat for spawning fish. The larvae seemed to be using the side channel for protection from the faster currents of the main Missouri River.

In 2007, the USFWS decided that raising fish in hatcheries should continue. They also said that monitoring population changes is important to see if human efforts are working. The 2007 findings also stressed the need to find the most likely spawning areas. They also want to identify any parasites or diseases that might affect the sturgeon's ability to reproduce. Finally, they want to explore engineering solutions that could create good habitats without increasing flood risks or reducing water for irrigation and recreation.

See also

In Spanish: Esturión pálido para niños

In Spanish: Esturión pálido para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |