Mandan facts for kids

Portrait of Sha-kó-ka, a Mandan girl,

by George Catlin, 1832 |

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,171 (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English • Hidatsa • formerly Mandan | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Hidatsa, Arikara |

The Mandan are a Native American tribe who have lived for hundreds of years mainly in what is now North Dakota. They are part of the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan people still live near the reservation. Others live across the United States and in Canada.

Historically, the Mandan lived along the Upper Missouri River and two smaller rivers: the Heart and Knife rivers. This area is in present-day North and South Dakota. They spoke Mandan, a Siouan language. The Mandan developed a settled farming culture. They built permanent villages with large, round earth lodges. Some of these lodges were about 12 meters (40 feet) wide and surrounded a central open area. Families related through the mother lived in these lodges. The Mandan were skilled traders. They often traded their extra corn with other tribes for bison meat and fat. Besides food, they also traded for horses, guns, and other goods.

Contents

Mandan Population Over Time

The Mandan population was around 3,600 in the early 1700s. Before Europeans arrived, it is thought there were 10,000 to 15,000 Mandan people. A widespread smallpox disease in 1781 greatly reduced their numbers. The people had to leave several villages. Some Hidatsa people also joined them in fewer villages. By 1836, there were more than 1,600 Mandan. But after another smallpox outbreak in 1836-37, their numbers dropped to an estimated 125 by 1838.

In the 1900s, the Mandan population began to grow again. In the 1990s, 6,000 people were part of the Three Affiliated Tribes. In the 2010 Census, 1,171 people said they had Mandan ancestors. About 365 of them were full-blood Mandan, and 806 had some Mandan ancestry.

What Does "Mandan" Mean?

The English name Mandan comes from the French-Canadian explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye. In 1738, he heard the name Mantannes from his Assiniboine guides. The Assiniboine called the Mandan Mayádąna. Other nearby Siouan language speakers had similar names for the Mandan. For example, the Teton called them Miwáthaŋni.

The Mandan used different names for themselves. Before the smallpox outbreak of 1837-1838, they used Numakaki (Nųmą́khų́·ki) or Rųwą́ʔka·ki. This meant "many men, people" and included all Mandan. After the epidemic, they used Nueta (Nų́ʔetaa), meaning "ourselves, our people." This name was originally for Mandan villagers living on the west side of the Missouri River. Later, Nų́ʔetaa was used for the whole tribe.

Mandan Language

The Mandan language or Nų́ų́ʔetaa íroo is part of the Siouan language family. It was once thought to be closely related to the languages of the Hidatsa and the Crow. However, because Mandan has been in contact with Hidatsa and Crow for many years, their exact relationship is unclear. For this reason, experts often classify Mandan as its own branch of the Siouan family.

Mandan had two main dialects: Nuptare and Nuetare. Only the Nuptare dialect survived into the 1900s. All speakers of Nuptare also spoke Hidatsa. In 1999, there were only six people who spoke Mandan fluently. As of 2010, schools in the area have programs to help students learn the language.

Mandan has different grammar forms depending on if you are talking to a man or a woman. For example, questions asked of men use the suffix -oʔša, while questions for women use -oʔrą. Mandan, like many other North American languages, uses sounds to show size or intensity. For example:

- síre means "yellow"

- šíre means "tawny" (a brownish-orange color)

- xíre means "brown"

Mandan History

Early History and Where They Came From

The exact beginnings of the Mandan people are not fully known. Some language studies suggest that the Mandan language might be related to the language of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) people from Wisconsin. Scholars think the Mandan's ancestors might have lived in Wisconsin at one time. This idea is supported by their oral history, which says they came from an eastern place near a lake.

Many scholars believe that, like other Siouan-speaking people, the Mandan came from the area of the mid-Mississippi River and Ohio River valleys. If this is true, the Mandan would have moved north into the Missouri River Valley and the Heart River in North Dakota. This is where Europeans first met the Mandan tribe. This move likely happened between 1000 CE and the 1200s, after they started growing corn. This time period had warmer, wetter weather, which was good for their farming.

After arriving at the Heart River, the Mandan built several villages. The largest ones were at the mouth of the river. Archeological findings show that the defenses of these villages changed over time. As their populations got smaller, they built new ditches and fences around smaller areas.

One village, called Double Ditch Village, was on the east side of the Missouri River, north of where Bismarck is today. The Rupture Mandan lived there for almost 300 years. Today, you can still see dips in the ground where their lodges were. There are also smaller dips where they stored dried corn. The village is named for two defensive trenches built outside the lodge area. Building these defenses often happened during dry periods when people would raid each other for food.

At some point, the Hidatsa people also moved into the area. They also spoke a Siouan language. Mandan stories say that the Hidatsa were a nomadic tribe until the Mandan taught them how to build permanent villages and farm. The Hidatsa and Mandan stayed friends. The Hidatsa built villages north of the Mandan on the Knife River.

Later, the Pawnee and Arikara moved north along the Missouri River. They spoke a Caddoan language. The Arikara were often rivals with the Mandan, even though both tribes were farmers. They built a settlement called Crow Creek village on a cliff above the Missouri.

The Mandan were divided into groups called bands. The Nup'tadi was the largest group. Other bands included the Is'tope ("those who tattooed themselves"), Ma'nana'r ("those who quarreled"), Nu'itadi ("our people"), and the Awi'ka-xa / Awigaxa. The Nup'tadi and Nu'itadi lived on both sides of the Missouri River. The Awigaxa lived further upstream at the Painted Woods.

All the bands farmed a lot. The women did the farming, including drying and preparing corn. The Mandan-Hidatsa villages were major trading centers in the Great Plains. They traded crops and other goods that came from as far away as the Pacific Northwest Coast. Items found at their sites show trade with areas like the Tennessee River, Florida, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard.

The Mandan slowly moved upriver and gathered in present-day North Dakota by the 1400s. From 1500 to about 1782, the Mandan reached their peak in population and power. Their villages became more crowded and had stronger defenses, like at Huff Village. It had 115 large lodges with over 1,000 people.

The bands did not move much along the river until the late 1700s. This was after their populations dropped sharply due to smallpox and other diseases.

First Meetings with Europeans

The first European known to visit the Mandan was the French Canadian trader Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye in 1738. The Mandans welcomed him into their village. At that time, an estimated 15,000 Mandan lived in nine strong villages on the Heart River. Some villages had as many as 1,000 lodges. Vérendrye said the Mandans were a large, powerful, and wealthy nation. They controlled trade with other Native Americans from both the north and the south.

The Mandan got Horses in the mid-1700s from the Apache to the South. The Mandan used horses for travel, carrying goods, and hunting. Horses helped them expand their hunting areas on the Plains. When the French from Canada arrived in the 1700s, it created a trading link. The Mandan became middlemen in the trade of furs, horses, guns, crops, and buffalo products. Spanish traders and officials in St. Louis also tried to trade with the Mandan. They wanted to stop the English and Americans from trading in the region. But the Mandan traded openly with everyone.

A smallpox disease started in Mexico City in 1779-1780. It slowly spread north through trade and conflicts, reaching the northern plains in 1781. The Mandan lost so many people that their number of clans (family groups) went from thirteen to seven. Three clan names from villages west of the Missouri were lost completely. They later moved north about 25 miles and joined into two villages, one on each side of the river. The much smaller Hidatsa people also joined them for protection. During and after the disease, they were attacked by Lakota Sioux and Crow warriors.

In 1796, the Welsh explorer John Evans visited the Mandan. He hoped to find proof that their language had Welsh words. Many Europeans believed there were Welsh Indians in these remote areas. Evans spent the winter of 1796–97 with the Mandan but found no evidence of any Welsh influence.

British and French Canadians from the north made more than twenty fur-trading trips to the Hidatsa and Mandan villages between 1794 and 1800.

By 1804, when Lewis and Clark visited the tribe, the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox and attacks from Assiniboine, Lakota, and Arikara tribes. (Later, the Mandan and Arikara joined together against the Lakota.) The nine Mandan villages had combined into two in the 1780s. But the Mandan were still very welcoming. The Lewis and Clark expedition stopped near their villages for the winter because of this hospitality. The expedition built a settlement they called Fort Mandan. Here, Lewis and Clark first met Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who had been captured. Sacagawea went with the expedition as they traveled west. She helped them with information and translating as they went toward the Pacific Ocean. When they returned to the Mandan villages, Lewis and Clark took the Mandan Chief Sheheke (Coyote or Big White) with them to Washington to meet President Thomas Jefferson. Chief Sheheke returned to the upper Missouri. He had survived the smallpox of 1781, but in 1812, Chief Sheheke was killed in a battle with the Hidatsa.

In 1825, the Mandans signed a peace treaty with the Atkinson-O'Fallon Expedition. The treaty said that the Mandans would recognize the United States' authority. It also said they lived on U.S. land and would let the U.S. control all trade. The Mandan and the United States Army never fought in open warfare.

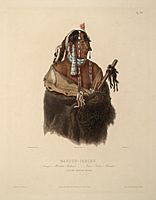

In 1832, artist George Catlin visited the Mandan near Fort Clark. Catlin painted scenes of Mandan life and portraits of chiefs, including Four Bears (Ma-to-toh-pe). His painting skills impressed Four Bears so much that he invited Catlin to watch the sacred annual Okipa ceremony. This was the first time a European person was allowed to see it. In the winter of 1833 and 1834, Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and Swiss artist Karl Bodmer also stayed with the Mandan.

Ideas About Early European Contact

In the 1700s, reports about Mandan lodges, religion, and some physical features (like blue or gray eyes and lighter hair) led to ideas about Europeans visiting America before Columbus. Catlin believed the Mandan were the "Welsh Indians" from old stories. He thought they were descendants of Prince Madoc and his followers who came to America from Wales around 1170. This idea was popular then, but most modern scholars do not agree with it.

Some people suggested that mixing with Norse (Viking) survivors might explain the "blond" people among the Mandan. However, archaeologists have found no physical evidence, like Viking tools or settlements, that would support a Viking presence in the American Midwest.

Conflicts and Changes (1785-1845)

Around 1785, Sioux Indians attacked and burned the Mandan village of Nuptadi. The Mandan saved the special "turtles" used in their Okipa ceremony. A Mandan woman named Scattercorn said, "When Nuptadi Village was burned by the Sioux... the turtles produced water which protected them..."

The Sioux became very powerful on the northern plains. A Lakota-allied Cheyenne warrior, George Bent, said that the Sioux moved to the Missouri River and often raided the Mandan and Arikara. This made it hard for the Mandan and Arikara to hunt buffalo on the plains.

The Arikara Indians were also sometimes enemies of the Mandan. Chief Four Bears's revenge on the Arikara, who had killed his brother, is a famous story.

The Mandan kept their villages protected with fences when there were threats.

Major battles took place. The Mandan winter count (a way of recording history) for 1835-1836 says: "We destroyed fifty tepees [of Sioux]. The following summer thirty men in a war party were killed." This large war party was defeated by Yanktonai Sioux Indians.

Mitutanka, a village where both Arikaras and some Mandans lived, was burned by Yankton Sioux Indians on January 9, 1839. One account said, "... the small Pox last year, very near annihilated the Whole [Mandan] tribe, and the Sioux has finished the Work of destruction by burning the village."

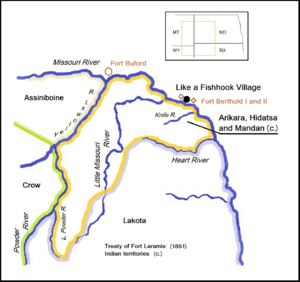

In 1845, the Hidatsa moved about 20 miles north, crossed the Missouri, and built Like-a-Fishhook Village. Many Mandans joined them for safety.

Smallpox Epidemic of 1837–38

The Mandan had suffered from smallpox before, starting in the 1500s. Epidemics happened every few decades. Between 1837 and 1838, another smallpox epidemic swept through the region. In June 1837, a steamboat from the American Fur Company traveled up the Missouri River. Its passengers and traders infected the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. At that time, about 1,600 Mandan lived in two villages. The disease killed 90% of the Mandan people, almost destroying their communities. Nearly all tribal members, including the chief, Four Bears, died. Estimates of survivors range from 27 to 150 people, with some sources saying 125. The survivors joined with the remaining Hidatsa in 1845 and moved upriver, where they built Like-a-Fishhook Village.

The Mandan believed they were infected by white people connected to the steamboat and Fort Clark. Chief Four Bears reportedly said, while sick, that those he thought of as brothers had become his worst enemies. Francis Chardon, who kept a journal at Fort Clark, wrote that the Hidatsa "swear vengeance against all the Whites, as they say the small pox was brought here by the S[team] B[oat]."

Late 1800s and 1900s

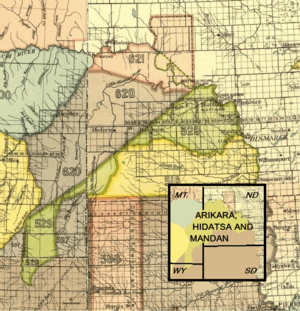

The Mandan were part of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. They shared a treaty area north of the Heart River with the Hidatsa and Arikara.

Soon, attacks on hunting groups by Lakota and other Sioux made it unsafe for the Mandan in their treaty area. The tribes asked the United States Army for help, and they continued to ask for aid until the Lakota were no longer the main power. Despite the treaty, the Mandan received little protection from U.S. forces.

In the summer of 1862, the Arikara joined the Mandan and Hidatsa in Like-a-Fishhook Village on the upper Missouri. All three tribes were forced to live outside their treaty area south of the Missouri because of frequent raids by the Lakota and other Sioux. Before the end of 1862, some Sioux Indians set fire to part of Like-a-Fishhook Village.

In June 1874, there was a "big war" near Like-a-Fishhook-Village. Colonel George Armstrong Custer could not stop a large group of Lakota warriors who were attacking the Mandan. Five Arikaras and one Mandan were killed by the Lakota. This attack was one of the last by the Lakota on the Three Tribes.

The Mandan joined with the Arikara in 1862. By this time, Like-a-Fishhook Village had become a major trading center in the region. However, by the 1880s, the village was abandoned. In the second half of the 1800s, the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) slowly lost control of some of their lands. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 recognized 12 million acres (49,000 km²) of land owned together by these tribes. But with the creation of the Fort Berthold Reservation in 1870, the government only recognized 8 million acres (32,000 km²). In 1880, another order took away 7 million acres (28,000 km²) of land outside the reservation's borders.

20th Century to Today

In the early 1900s, the government took more land. By 1910, the reservation was reduced to 900,000 acres (3,600 km²). This land is in Dunn, McKenzie, McLean, Mercer, Mountrail, and Ward counties in North Dakota.

Under the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, which encouraged tribes to rebuild their governments, the Mandan officially joined with the Hidatsa and Arikara. They wrote a constitution to elect their leaders and formed the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes.

In 1951, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers started building Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. This dam was for flood control and irrigation. It created Lake Sakakawea. The lake flooded parts of the Fort Berthold Reservation, including the villages of Fort Berthold and Elbowoods. The people from these villages were moved, and New Town was built for them.

While New Town was built for the displaced tribal members, the flooding caused much harm to the reservation's social and economic life. About one-quarter of the reservation's land was flooded. This land included some of the best farming areas that their economy depended on. The Mandan did not have other land that was as fertile for farming. Also, the flooding covered historic villages and important archaeological sites that had sacred meaning for the people.

Mandan Culture

Homes and Villages

The Mandan were known for their unique, large, round earthen lodges. More than one family lived in these homes. Their permanent villages were made up of these lodges. Women built and took care of each lodge. They were circular with a dome-shaped roof and a square hole at the top for smoke to escape. Four main pillars supported the lodge's frame. Wood timbers were placed against these, and the outside was covered with mats made from reeds and twigs. Then, it was covered with hay and earth. This protected the inside from rain, heat, and cold. The roof was strong enough for many adults and children to sit on. The lodge also had a covered entrance to protect from cold weather.

The inside was built around four large pillars that held up the roof. Mandan women designed, built, and owned these lodges. Ownership was passed down through the female family line. Lodges were usually about 12 meters (40 feet) wide. They could hold several families, up to 30 or 40 people, who were related through the older women. When a young man married, he moved into his wife's lodge, which she shared with her mother and sisters. Villages usually had around 120 lodges. You can see reconstructed lodges at Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park near Mandan, North Dakota, and the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

Originally, lodges were rectangular. But around 1500 CE, they started building them in a circular shape. By the late 1800s, the Mandan began building small log cabins, usually with two rooms. When traveling or hunting, the Mandan used skin tipis. Today, Mandan people live in modern homes.

Villages were usually built around a central open area used for games and ceremonies. In the middle of this area was a cedar tree surrounded by a wooden fence. This shrine represented "Lone Man," a key figure in Mandan religion. He was said to have built a wooden fence that saved villagers from a flooding river in North Dakota. Villages were often built on high cliffs above the river. Sometimes, villages were built where two rivers met, using the water as a natural barrier. Where there were few natural barriers, villages built defenses like ditches and wooden palisades (tall fences).

Family Life

The Mandan were originally divided into thirteen clans (family groups). This number was reduced to seven by 1781 due to population losses from smallpox. Ninety percent of the population died in the 1837-1838 smallpox epidemic. By 1950, only four clans remained.

Historically, clans were organized around successful hunters and their relatives. Each clan was expected to care for its members, including orphans and the elderly, from birth to death. The dead were traditionally cared for by their father's clan. Clans kept a sacred or medicine bundle, which held special objects believed to have sacred powers. Those who had these bundles were thought to have sacred powers from the spirits. They were seen as leaders of the clan and tribe. In historic times, medicine bundles could be bought, along with the knowledge of the ceremonies and rights connected to them. They could then be passed down to children.

Children were named ten days after birth in a ceremony that officially connected them to their family and clan. Girls were taught home skills, especially how to grow and prepare corn and other plants. They also learned how to prepare animal skins and meats, do needlework, and build and maintain a home. Boys were taught hunting and fishing. Boys began fasting for religious visions at age ten or eleven. Marriages among the Mandan were usually arranged by members of one's own clan, especially uncles. However, sometimes marriages happened without the parents' approval. Divorce was easy to get.

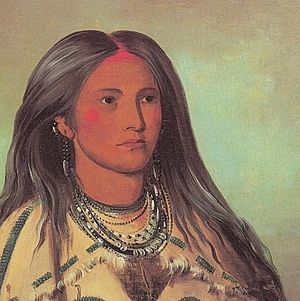

When a family member died, the father and his relatives would build a platform near the village to hold the body. The body would be placed with the head toward the northwest and feet to the southeast. Southeast is the direction of the Ohio River Valley, where the Mandan came from. The Mandan would not sleep in this direction because it was associated with death. After a ceremony to send the spirit away, the family would mourn at the platform for four days. After the body decayed and the platform collapsed, the bones would be gathered and buried. However, the skull was placed in a circle near the village. Family members would visit the skulls and talk to them, sometimes sharing their problems or telling jokes.

Mandan Economy and Food

Mandan people got food from farming, hunting, gathering wild plants, and trading. Corn was their main crop. They traded their extra corn with nomadic tribes for bison meat. Mandan gardens were often near river banks, where annual floods left the soil very fertile. Sometimes these gardens were miles from the villages. Women owned and cared for the gardens. They planted several types of corn, beans, and squash. Sunflowers were planted first in early April. As early as the 1400s, the Mandan town of Huff had enough storage pits to hold seventy thousand bushels of corn.

Hunting the buffalo was a very important part of Mandan life and ceremonies. They performed the Buffalo Dance ceremony at the start of each summer to call the buffalo to the village. Besides eating the meat, the Mandan used all parts of the buffalo, so nothing was wasted. The hides were used for buffalo-fur robes or were tanned into leather for clothing, bags, shelter, and other uses. The Mandan were known for their painted buffalo hides that often recorded historical events. Bones were carved into items like needles and fish hooks. Bones were also used in farming; for example, the scapula (shoulder blade) was used as a hoe-like tool for breaking the soil. The Mandan also trapped small mammals for food and hunted deer. Deer antlers were used to make rake-like tools for farming. Birds were hunted for meat and feathers, which were used for decoration. Archeological findings show that the Mandan also ate fish.

The Mandan and nearby Hidatsa villages were key trading centers on the Northern Plains. The Mandan sometimes traveled far to trade, but more often, nomadic plains people came to the upper Missouri villages to trade. For example, in the winter of 1804, William Clark recorded that thousands of Assiniboine Indians, as well as Cree and Cheyenne, came to trade. The Mandan traded corn for dried bison meat. They also traded horses with the Assiniboine for weapons, ammunition, and European goods. Clark noted that the Mandan got horses and leather tents from people to the west and southwest, such as the Crows, Cheyennes, Kiowas, and Arapahos.

Traditional Dress

Until the late 1800s, when Mandan people started wearing Western-style clothes, they commonly wore clothing made from the hides of buffalo, deer, and sheep. From these hides, they made tunics, dresses, buffalo-fur robes, moccasins, gloves, loincloths, and leggings. These items were often decorated with quills and bird feathers.

Mandan women wore ankle-length dresses made of deerskin or sheepskin. These were often tied at the waist with a wide belt. Sometimes the bottom edge of the dress was decorated with pieces of buffalo hoof. Under the dress, they wore leather leggings with ankle-high moccasins. Women wore their hair straight down in braids.

During the winter, men commonly wore deerskin tunics and leggings with moccasins. They also kept warm by wearing a robe made of buffalo fur. In the summer, however, they often wore only a loincloth made of deerskin or sheepskin. Unlike women, men wore various decorations in their hair. Their hair was parted across the top, with three sections hanging down in front. Sometimes the hair would hang down the nose and be curled upwards with a curling stick. The hair would hang to the shoulders on the side, and the back part would sometimes reach the waist. The long hair in the back would be gathered into braids, then covered with clay and spruce gum, and tied with deerskin cords. Feather headdresses were also often worn. Besides buffalo, elk, and deer hides, the Mandan also used ermine and white weasel hides for clothing.

Today, Mandan people wear traditionally inspired clothing and special outfits at powwows, ceremonies, and other important events.

Mandan Religion

The Mandan's religion and beliefs about the universe were very complex. They centered around a figure known as Lone Man. Lone Man was involved in many of their creation myths and one of their flood myths.

In their creation story, the world was made by two rival gods: the First Creator and the Lone Man. The Missouri River divided the two worlds these beings created. First Creator made the lands south of the river with hills, valleys, trees, buffalo, pronghorn antelope, and snakes. North of the river, Lone Man created the Great Plains, domesticated animals, birds, fish, and humans. The first humans lived underground near a large lake. Some adventurous humans climbed a grapevine to the surface and found the two worlds. After returning underground, they shared what they found and decided to return with many others. As they were climbing the grapevine, it broke, and half the Mandan were left underground.

According to Mandan beliefs, each person had four different, immortal souls. The first soul was white and often seen as a shooting star. The second soul was light brown and seen as a meadowlark. The third soul, called the lodge spirit, stayed at the lodge site after death forever. The final soul was black and would travel away from the village after death. These final souls lived like living people, in their own villages, farming and hunting.

The Okipa ceremony was a very important part of Mandan religious life. This complex ceremony was about the creation of the earth. It was first recorded by George Catlin. A man would volunteer to be the Okipa Maker. He would sponsor the preparations and food needed. Preparations took much of a year, as there were days of events where many people were hosted.

The ceremony began with a Bison Dance, to call the buffalo to the people. It was followed by various physical challenges through which warriors showed their courage and gained the approval of the spirits.

Those who finished the ceremony were seen as being honored by the spirits. Those who completed the ceremony twice would gain lasting fame among the tribe. Chief Four Bears, or Ma-to-toh-pe, completed this ceremony twice. The last Okipa ceremony was performed in 1889. However, the ceremony was brought back in a slightly different form in 1983.

Mandan People Today

The Mandan and the two related tribes, the Hidatsa (Siouan) and Arikara (Caddoan), have intermarried. But as a whole, they still keep the different traditions of their ancestors. The tribal residents have recovered from the difficulties of being moved in the 1950s.

They built the Four Bears Casino and Lodge in 1993. This attracts tourists and creates money and jobs for the reservation.

The newest addition to the New Town area is the new Four Bears Bridge. It was built by the three tribes and the North Dakota Department of Transportation working together. The bridge crosses the Missouri River. It replaced an older Four Bears Bridge built in 1955. The new bridge, which is the largest bridge in North Dakota, is decorated with medallions celebrating the cultures of the three tribes. The bridge opened to traffic on September 2, 2005, and was officially opened in a ceremony on October 3.

Image gallery

-

Mandan Chief Ma-to-toh-pe or Four Bears, by George Catlin

Images for kids

-

Lewis and Clark meeting the Mandan Indians, by Charles Marion Russell, 1897

See also

In Spanish: Mandan para niños

In Spanish: Mandan para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |