Madoc facts for kids

Madoc, also known as Madog ab Owain Gwynedd, was a Welsh prince from an old story. People say he sailed to America in 1170. This was more than 300 years before Christopher Columbus's famous trip in 1492.

The story says Madoc was a son of Owain Gwynedd, a real Welsh king. He supposedly left Wales to escape fighting among his family. This "Madoc story" grew from old tales about a Welsh hero's sea journey. It became very popular during the time of Queen Elizabeth I in England. Writers used the story to claim that England had found North America first. This would mean England had a right to own the land.

The Madoc story stayed popular for many years. Later, people added that Madoc's sailors married Native Americans. They believed that Welsh-speaking people still lived somewhere in the United States. These "Welsh Indians" were even given credit for building certain landmarks. Many explorers went looking for them. The Madoc story is often discussed when people talk about whether others reached America before Columbus. However, there is no strong proof that Madoc or his voyages actually happened.

Contents

The Story of Prince Madoc

Madoc's father, Owain Gwynedd, was a real king in Wales. He ruled in the 1100s. Many people think he was one of the greatest Welsh rulers of the Middle Ages. His time as king was full of battles. He fought other Welsh princes and also Henry II of England. When King Owain died in 1170, a big fight started among his many children. They all wanted to be the next ruler.

The story says Madoc was very sad about this family fighting. So, he and his brother, Rhirid, decided to sail away. They supposedly left from a place called Llandrillo in Wales. They wanted to explore the western ocean. The legend says they found a rich new land in 1170. About a hundred men, women, and children got off the ships to start a new home there.

According to the tale, Madoc and some others then went back to Wales. They wanted to find more people to join their new colony. After gathering eleven ships and 120 more people, they sailed west again. The story says they landed in "Mexico." Madoc and his new settlers were never seen in Wales again.

People have suggested many places where Madoc might have landed. These include Mobile, Alabama; Florida; and even parts of South America. The story says Madoc's settlers traveled far into North America. They built structures and met different Native American tribes. Some tales even say they founded great civilizations like the Aztecs, the Maya, and the Inca.

Tales of Welsh Indians

In 1608, an explorer named Peter Wynne wrote a letter. He said some people in his group thought the language of the Monacan tribe sounded like Welsh. Wynne spoke Welsh, and they asked him to try to understand them.

Another early story comes from Reverend Morgan Jones. He said he was captured in North Carolina in 1669. His captors were from a tribe called the Doeg. Jones said the chief spared his life when he heard Jones speak Welsh. The chief understood the language. Jones claimed he lived with the Doeg for several months. He preached the Christian message in Welsh. He then returned to the British colonies and wrote about his adventure. However, some historians think this story might have been a joke.

For a long time, people believed that a place called "Devil's Backbone" in Kentucky was home to Welsh-speaking Native Americans. An explorer named John Evans even went looking for Welsh-descended tribes.

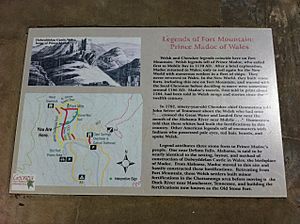

In Georgia, there are legends about Welsh people connected to a mysterious rock wall. This wall is on Fort Mountain. Some believe that stories of "Welsh Indians" might have influenced the local Cherokee traditions about this ruin.

In Alabama, there's a theory about "Welsh Caves" in DeSoto State Park. People thought Madoc's group built them. This is because local tribes were not known for doing such stonework.

In 1810, John Sevier, the first governor of Tennessee, wrote about a talk he had with a Cherokee chief. The chief supposedly told him that old forts along the Alabama River were built by white people called "Welsh." He said the Welsh built them to protect themselves from the Cherokee. Sevier also claimed that six skeletons in brass armor with Welsh symbols were found in 1799. He believed Madoc and the Welsh were the first Europeans in Alabama.

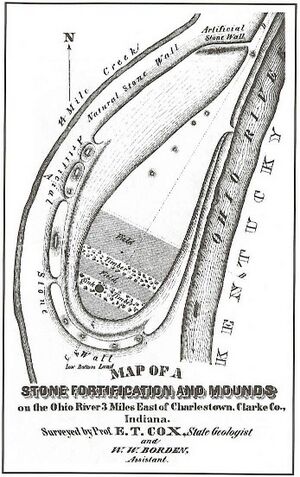

In 1824, Thomas S. Hinde wrote a letter about the Madoc story. He claimed to have heard from many people that Welsh people came to America in the 1100s. He also mentioned the discovery of six soldiers with Welsh symbols on their armor near Jeffersonville, Indiana.

Searching for Welsh Indians

Thomas Jefferson, who later became president, had heard about Welsh-speaking Native American tribes. In a letter from 1804, he asked Meriwether Lewis to look for these Welsh Indians. They were supposedly "up the Missouri" River. The historian Stephen E. Ambrose wrote that Jefferson truly believed the Madoc story. He told the Lewis and Clark Expedition to find Madoc's descendants.

The Mandan People

Many different tribes were suggested as "Welsh Indians." Eventually, the legend focused on the Mandan people. People thought the Mandan were different from their neighbors in their culture, language, and looks. The painter George Catlin believed the Mandans were descendants of Madoc. He wrote about this in his book North American Indians (1841). Catlin noticed that the Mandan's round boats, called bull boats, were similar to Welsh coracles. He also thought the Mandan villages had advanced buildings. He believed Europeans must have taught them how to build them.

Later Writings and Legacy

Most historians today believe the Madoc story is a myth. There is no strong historical proof for it. However, the legend has been a popular topic for poets. The most famous poem in English is Madoc by Robert Southey, written in 1805. Southey used the story to share his ideas about freedom and equality. He even wrote the poem to help pay for a trip to America. He hoped to start an ideal community there.

The Madoc story has also inspired places to be named after him. The township of Madoc, Ontario, and the nearby village of Madoc in Canada are named in his honor. There are also guest houses and pubs with his name. The Welsh town of Porthmadog and the village of Tremadog are named after a developer named William Alexander Madocks. But the legend of Prince Madoc also influenced these names.

A research ship owned by the University of Wales is called the Prince Madog. It started service in 2001.

At Fort Mountain State Park in Georgia, there was a plaque. It told a story from the 1800s about the old stone wall there. The plaque said that the Cherokees believed "a people called Welsh" built a fort on the mountain long ago. This was to defend against Native American attacks. This plaque has since been changed. It no longer mentions Madoc or the Welsh.

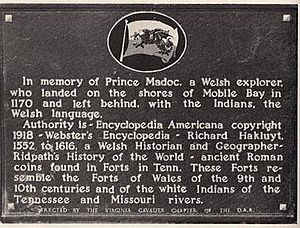

In 1953, a group called the Daughters of the American Revolution put up a plaque. It was at Fort Morgan in Alabama. The plaque said:

In memory of Prince Madoc a Welsh explorer who landed on the shores of Mobile Bay in 1170 and left behind with the Indians the Welsh language.

The Alabama Parks Service removed this plaque in 2008. It is now in storage. There has been much discussion about putting the plaque back up.

See also

In Spanish: Madoc para niños

In Spanish: Madoc para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |