Robert Southey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Southey

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 12 August 1813 – 21 March 1843 |

|

| Monarch | George III George IV William IV Victoria |

| Preceded by | Henry James Pye |

| Succeeded by | William Wordsworth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 August 1774 Bristol, England |

| Died | 21 March 1843 (aged 68) London, England |

| Spouses |

|

| Occupation | Poet, historian, biographer and essayist |

Robert Southey (born August 12, 1774 – died March 21, 1843) was an English poet. He was part of the Romantic movement. He served as the Poet Laureate from 1813 until he passed away.

Like other Lake Poets such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey started with radical ideas. However, he slowly became more traditional. He grew to respect Britain and its government. Other Romantic poets, like Byron, criticized him. They said he supported the government for money and fame. Southey is best known for his poem "After Blenheim". He also wrote the first version of "Goldilocks and the Three Bears".

Contents

Robert Southey's Life Story

Robert Southey was born in Bristol, England. His parents were Robert Southey and Margaret Hill. He went to Westminster School in London. He was asked to leave for writing an article. The article was in a magazine he started called The Flagellant.

Southey later attended Balliol College, Oxford. He felt he didn't learn much there. He once said, "All I learnt was a little swimming... and a little boating." While at Oxford, he wrote a play called Wat Tyler. This play was published later by his enemies to embarrass him.

In 1794, Southey worked with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. They wrote The Fall of Robespierre together. Southey also published his first collection of poems that year. Around the same time, Southey, Coleridge, and others dreamed of starting an ideal community. They called this idea "pantisocracy". They hoped to create it in America.

In 1795, he married Edith Fricker. Her sister Sara married Coleridge. That same year, Southey traveled to Portugal. He wrote Joan of Arc, which came out in 1796. He then wrote many ballads. In 1800, he visited Spain. After returning, he settled in the Lake District.

In 1799, Southey and Coleridge took part in early experiments. They tried nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas. These experiments were led by scientist Humphry Davy.

Southey wrote a lot of books and poems. In 1807, he started receiving money from the government. From 1809, he worked closely with the Quarterly Review magazine. This job provided most of his income. He became Poet Laureate in 1813. He later found this job quite difficult.

In 1821, Southey wrote A Vision of Judgment. This poem honored King George III. In the introduction, he criticized Byron. Byron responded with his own parody poem. Byron also often made fun of Southey in his poem Don Juan.

In 1837, Edith, Southey's wife, passed away. He married Caroline Anne Bowles, who was also a poet, in 1839. This marriage faced challenges. Southey's memory began to fade. He died on March 21, 1843. He was buried in the churchyard of Crosthwaite Church in Keswick. His friend, William Wordsworth, wrote an epitaph for his memorial inside the church.

Southey was also a very active letter writer. He was a literary scholar, essay writer, historian, and biographer. He wrote life stories of famous people. These included John Bunyan, John Wesley, and Horatio Nelson. His book about Nelson has been printed many times since 1813. It was even made into a British film in 1926.

He was a kind person, especially to Coleridge's family. However, he made some enemies. People like Hazlitt and Byron felt he had changed his beliefs. They thought he accepted money and fame. They believed he gave up his youthful ideals.

Robert Southey's Political Views

Robert Southey first supported the French Revolution. He had radical ideas. But like his friends Wordsworth and Coleridge, he became more traditional. As Poet Laureate, he was supported by the Tory government. From 1807, he received money from them each year. He strongly supported the government led by Lord Liverpool.

Southey spoke against changes to Parliament. He called it "the railroad to ruin." He blamed the Peterloo Massacre on a "rabble" (a disorderly crowd). He said they were injured by government soldiers. He also did not support Catholic emancipation. In 1817, he suggested that people who wrote "libel" (false harmful statements) or "sedition" (words encouraging rebellion) should be sent away. He believed such writers were "disturbing the quiet" of people.

However, Southey also had some modern ideas for his time. For example, he was one of the first to criticize the problems caused by new factories. He was shocked by the poor living conditions in cities like Birmingham and Manchester. He especially spoke out against children working in factories. He supported the ideas of Robert Owen, a pioneer in socialism. Southey also believed the government should create public works to keep people employed. He called for education for everyone.

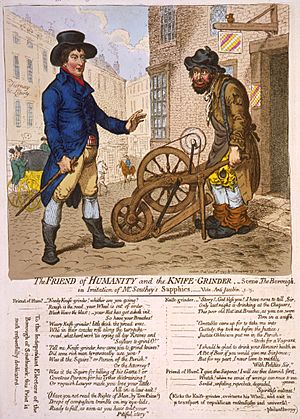

Because he changed his political views, some people criticized Southey. They saw him as someone who sold out for money and respectability.

In 1817, a play he wrote in 1794, Wat Tyler, was secretly published. His enemies did this to embarrass him. They wanted to show how he had changed from a radical poet to a government supporter. William Hazlitt was one of his harshest critics. He wrote that Southey had "wedded with an elderly and not very reputable lady, called Legitimacy."

Southey mostly ignored his critics. But he had to defend himself when William Smith, a Member of Parliament, attacked him. Southey wrote an open letter to Smith. He explained that he always wanted to help people. He said he only changed his mind about "the means" to do it. He wrote that as he understood his country's rules better, he learned to "love, and to revere, and to defend them."

Another critic was Thomas Love Peacock. He made fun of Southey in his 1817 book Melincourt.

Southey was often mocked for writing poems praising the king. Lord Byron did this in his long dedication of Don Juan to Southey. In the poem, Byron called Southey "insolent, narrow and shabby." This was because Byron didn't respect Southey's writing. He also disliked Southey's change to traditional views.

In response, Southey criticized what he called the Satanic School of poets. He did this in the introduction to his poem, A Vision of Judgement. He didn't name Byron, but it was clear who he meant. Byron then wrote The Vision of Judgment, which was a parody of Southey's poem.

In 1826, the Earl of Radnor had Southey elected as a Member of Parliament. This was for a seat called Downton. The Earl admired Southey's work. However, Southey refused the seat. He said he didn't have enough money to live in London. He also preferred to write about the Church of England rather than speak in Parliament.

In 1835, Southey turned down an offer to become a baronet. But he accepted a yearly pension of £300 from Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.

Awards and Groups

Southey became a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1822. He was also a member of the Royal Spanish Academy.

Some of Robert Southey's Works

- Harold, or, The Castle of Morford (an unpublished Robin Hood novel that Southey wrote in 1791).

- The Fall of Robespierre (1794) (with Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

- Poems:containing the Retrospect, Odes, Elegies, Sonnets, &c. (with Robert Lovell)

- Joan of Arc (1796)

- Icelandic Poetry, or The Edda of Sæmund (contributing an introductory epistle to A. S. Cottle's translations, 1797)

- Poems (1797–1799)

- Letters Written During a Short Residence in Spain and Portugal (1797)

- St. Patrick's Purgatory (1798)

- After Blenheim (1798)

- The Devil's Thoughts (1799). Revised ed. pub. in 1827 as "The Devil's Walk". (with Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

- English Eclogues (1799)

- The Old Man's Comforts and How He Gained Them (1799)

- Thalaba the Destroyer (1801)

- The Inchcape Rock (1802)

- Madoc (1805)

- Letters from England: By Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella (1807), the observations of a fictitious Spaniard.

- Chronicle of the Cid, from the Spanish (1808)

- The Curse of Kehama (1810)

- History of Brazil (3 vols.) (1810–1819)

- The Life of Horatio, Lord Viscount Nelson (1813)

- Roderick the Last of the Goths (1814)

- Journal of a tour in the Netherlands in the autumn of 1815 (1902)

- Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (1817)

- Wat Tyler: A Dramatic Poem (1817; written in 1794)

- Cataract of Lodore (1820)

- The Life of Wesley; and Rise and Progress of Methodism (2 vols.) (1820)

- What Are Little Boys Made Of? (1820)

- A Vision of Judgement (1821)

- History of the Peninsular War, 1807–1814 (3 vols.) (1823–1832)

- Sir Thomas More; or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1829)

- The Works of William Cowper, 15 vols., ed. (1833–1837)

- Lives of the British Admirals, with an Introductory View of the Naval History of England (5 vols.) (1833–40); republished as "English Seamen" in 1895.

- The Doctor (7 vols.) (1834–1847). Includes The Story of the Three Bears (1837).

- The Poetical Works of Robert Southey, Collected by Himself (1837)

See also

In Spanish: Robert Southey para niños

In Spanish: Robert Southey para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |