William Hazlitt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Hazlitt

|

|

|---|---|

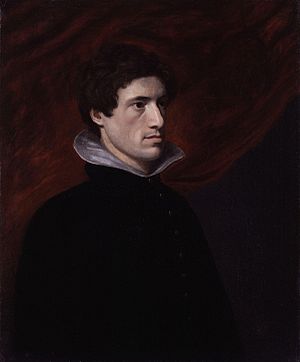

A self-portrait from about 1802

|

|

| Born | 10 April 1778 Maidstone, Kent, England |

| Died | 18 September 1830 (aged 52) Soho, London, England |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | English |

| Education | New College at Hackney |

| Notable works | Characters of Shakespear's Plays, Table-Talk, The Spirit of the Age |

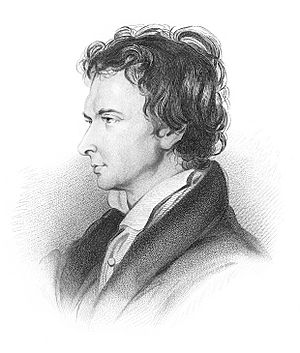

William Hazlitt (born April 10, 1778 – died September 18, 1830) was an English writer. He was known for his essays, and for being a critic of plays and books. He was also a painter and a thinker (philosopher). Today, many people see him as one of the best essayists and critics in English history. He is often compared to famous writers like Samuel Johnson and George Orwell. Hazlitt was also thought to be the best art critic of his time. Even though he is highly respected by experts, his writings are not widely read today.

During his life, he became friends with many important writers of the 1800s. These included Charles and Mary Lamb, Stendhal, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and John Keats.

Contents

William Hazlitt's Life and Work

Early Life and Education

Family Background

William Hazlitt's family were Irish Protestants. They moved from County Antrim to County Tipperary in the early 1700s. His father, also named William Hazlitt, studied at the University of Glasgow. He became a Unitarian minister in England.

In 1766, his father married Grace Loftus. They had many children, but only three lived past infancy. His older brother, John Hazlitt, became a portrait painter. His sister, Margaret, was born in 1770.

Childhood Years

William was the youngest of the children who survived. He was born in Maidstone in 1778. When he was two, his family started moving around a lot. They lived in Ireland and then in the United States. His father tried to find work as a minister there.

In 1786, his family returned to England. They settled in Wem, a town in Shropshire. Hazlitt didn't remember much from his time in America.

Schooling and Learning

Hazlitt was taught at home and at a local school. When he was 13, his writing was printed for the first time. The Shrewsbury Chronicle published his letter. In it, he spoke against riots in Birmingham. These riots were about Joseph Priestley's support for the French Revolution.

In 1793, his father sent him to a Unitarian school. It was called New College at Hackney. He studied there for about two years. This time had a big impact on him.

The school taught many subjects. These included Greek and Latin classics, math, history, and science. Hazlitt also learned about religion. Teachers like Joseph Priestley encouraged debates on political issues. This was during the exciting time of the French Revolution.

Hazlitt started to change his mind about religion. He left Hackney before becoming a minister. He kept a strong belief in freedom and human rights. He also believed that the mind could spread knowledge. This could help people become better. He hated unfair rule and cruelty.

Becoming a Philosopher

Around 1795, Hazlitt returned home. He started focusing on modern philosophy and politics. In 1794, he met William Godwin, a famous thinker. Godwin's book Political Justice was very popular.

Hazlitt studied many thinkers. These included John Locke, David Hartley, and David Hume. He also read French thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau became a very important influence on him. Hazlitt also admired the writing style of Edmund Burke.

Hazlitt wanted to become a philosopher. He worked on a book about the "natural disinterestedness of the human mind." This meant he wanted to prove that people are not naturally selfish. He believed people could act kindly without expecting something in return. This book was published in 1805. Even later in life, he always saw himself as a philosopher.

Around 1796, Hazlitt found new inspiration. He met Joseph Fawcett, a retired clergyman. Fawcett loved all kinds of literature. He discussed radical ideas and literature with Hazlitt. This helped Hazlitt develop his wide taste in writing.

Hazlitt also spent time in London. He enjoyed the city's theatres. This experience later helped his writing about plays. He felt frustrated because he couldn't easily write down his thoughts. Then, he met Samuel Taylor Coleridge. This meeting changed his life and writing career.

Poetry, Painting, and Marriage

Meeting Famous Poets

On January 14, 1798, Hazlitt met Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge was preaching at a church in Shrewsbury. Hazlitt was amazed by Coleridge's brilliant speaking. He later wrote that it was like "Poetry and Philosophy had met together." He called Coleridge "the only person I ever knew who answered to the idea of a man of genius." Hazlitt felt that Coleridge helped him learn to express his thoughts.

In April, Hazlitt visited Coleridge. He also met William Wordsworth at his home. Hazlitt was very impressed by Wordsworth. He saw that Wordsworth had the mind of a true poet. Reading Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads showed him a "new style and a new spirit in poetry."

All three men believed in freedom and human rights. They walked and talked about poetry, philosophy, and politics. This meeting made Hazlitt realize that poetry, like philosophy, was important. It encouraged him to continue his own thinking and writing.

Becoming a Painter

Hazlitt decided not to become a minister. He needed to earn a living. He became very interested in painting around 1798. His older brother, John, was a successful painter of small portraits. William started taking lessons from John.

Hazlitt visited art galleries and began painting portraits. He painted in a style similar to Rembrandt. He traveled between London and the countryside to find work. In 1802, a portrait he painted of his father was shown at the Royal Academy.

Later in 1802, Hazlitt went to Paris. He was asked to copy famous paintings by Old Masters at The Louvre museum. This was a great chance for him. He spent three months studying the art. This experience later helped him write about art. He also saw Napoleon, whom he admired greatly.

Back in England, Hazlitt continued to paint portraits. He painted Coleridge and Wordsworth. Neither poet was fully happy with their portraits. However, Wordsworth and Robert Southey thought his portrait of Coleridge was very good.

Marriage and Family Life

On March 22, 1803, Hazlitt met Charles Lamb and his sister Mary Lamb at a dinner party. William and Charles became close friends. Their friendship lasted for many years. Hazlitt also liked Mary. He thought she was a very sensible woman. Hazlitt often visited the Lambs and attended their literary gatherings.

Hazlitt had few painting jobs. So, he worked on his philosophy book. It was called An Essay on the Principles of Human Action. It was published in 1805. This book didn't make him famous or rich. But it showed he understood philosophy. He then got work to shorten another philosophy book.

He also started writing about politics. He published a pamphlet called Free Thoughts on Public Affairs in 1806. He also wrote for William Cobbett's Weekly Political Register. He strongly criticized Thomas Malthus's ideas about population. Hazlitt argued that Malthus's ideas were unfair to the poor. His writing style became very sharp and clear during this time.

In May 1808, Hazlitt married Sarah Stoddart. She was a friend of Mary Lamb. Sarah's brother, John Stoddart, gave them money each year. Hazlitt didn't like being supported by his brother-in-law. Their marriage was not based on deep love. But it worked for a while. They lived in Winterslow, a village near Salisbury. They had three sons, but only one, also named William, lived past infancy.

As a family man, Hazlitt needed more money. He wrote an English grammar book, published in 1809. He also helped finish the memoirs of Thomas Holcroft, a writer and activist. Hazlitt continued to paint landscapes and portraits.

In 1812, Hazlitt started giving lectures. He talked about British philosophers in London. These lectures brought him some attention and much-needed money. He also shared his own ideas.

By 1812, Hazlitt mostly stopped trying to be a painter. He felt his paintings were not as good as those of masters like Rembrandt. He also refused to flatter people in his portraits. This meant he didn't get many clients. But new opportunities were waiting for him.

Journalist and Essayist

Starting in Journalism

In October 1812, Hazlitt became a reporter for The Morning Chronicle. He met John Hunt and his brother Leigh Hunt. Leigh Hunt was a poet and essayist. Hazlitt admired them and became friends with Leigh Hunt. He started writing essays for The Examiner in 1813. He also wrote about plays, books, and politics for the Chronicle. By 1814, he was writing for The Champion too.

By 1814, Hazlitt was a successful journalist. He earned a good living. He moved his family to a house at 19 York Street in Westminster. This house had once been lived in by the poet John Milton, whom Hazlitt greatly admired. His landlord was the philosopher Jeremy Bentham. Hazlitt wrote a lot about both Milton and Bentham.

His group of friends grew. However, he was only truly close to the Lambs and Leigh Hunt. Hazlitt found it hard to get along with others. He often spoke his mind, even if it was rude. He didn't like people who stopped supporting freedom.

In 1814, Hazlitt wrote a review of Wordsworth's poem The Excursion. He praised the poem's power but criticized Wordsworth's self-centeredness. Wordsworth was very angry, and their friendship cooled.

Hazlitt still thought of himself as a "metaphysician" (a deep thinker). But he became comfortable as a journalist. He started writing for The Edinburgh Review, a respected magazine. This made him proud.

Challenges and Success

In 1815, Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo. Hazlitt had admired Napoleon as a hero for common people. This defeat was a personal blow to him. He felt it was the end of hope for ordinary people against kings.

His marriage got worse, and he spent more time away from home. He wrote about plays, which gave him an excuse to go to the theatre. He also wrote political articles. He attacked anyone he felt ignored the rights of common people.

To relax, Hazlitt played a game similar to handball called Fives. He played with great energy. This love for sports led him to write about competition and human skill. His essays like "The Indian Jugglers" came from these thoughts.

In 1817, a collection of his essays was published. It was called The Round Table. These essays covered many topics. They included Shakespeare, Milton, art, and social issues. He wrote about the acting of Edmund Kean, a famous actor.

Hazlitt's writing style started to become unique. He used quotes from literature. He often made sharp observations about human nature. For example, he wrote that "All country people hate each other." He also sometimes misquoted things. But his insights and style made his essays very distinct.

New Books and More Trouble

Hazlitt's marriage continued to decline. He was writing a lot to earn money. He was also getting sick often. He decided to focus on Shakespeare's plays themselves. This led to his book Characters of Shakespear's Plays (1817).

His approach was new. He offered personal and enthusiastic thoughts on the plays. He didn't just list strengths and weaknesses. He shared his love for Shakespeare with his readers.

The book was very popular. The first edition sold out quickly. It also received good reviews. This success helped Hazlitt with his debts. However, his reputation was also being hurt. He had criticized Wordsworth and Coleridge. They spread rumors about him.

In 1818, Hazlitt gave lectures on "the English Poets." These lectures were successful. He met Peter George Patmore, who became a close friend. His lectures were published as books. He also published his drama criticism and a second edition of his Shakespeare book. He gave more lectures on "the English Comic Writers" and dramatists from Shakespeare's time.

But more trouble came. Hazlitt was attacked by Tory magazines like The Quarterly Review and Blackwood's Magazine. They called him names and accused him of being ignorant. Hazlitt sued Blackwood's and won. He also wrote a strong defense of himself. But the attacks hurt his reputation. It became harder for him to get his works published. He struggled to make a living again.

Loneliness and a Difficult Love Story

Despite the attacks, Hazlitt had a few admirers. The poet John Keats was one of them. Keats attended Hazlitt's lectures and became his friend. They read each other's work. Keats was influenced by Hazlitt's idea of "disinterested sympathy." Hazlitt later said that Keats was the most promising young poet. He included Keats's poems in a collection of British poetry.

Other admirers included the diarist Henry Crabb Robinson and the novelist Mary Russell Mitford. But the rumors and attacks made it hard for Hazlitt to earn money.

By 1819, his marriage had completely failed. He couldn't pay rent and was evicted from his home. His wife, Sarah, moved out with their son. They were separated, though they remained on speaking terms.

Hazlitt often went to the countryside, staying at the "Winterslow Hut" inn. This was for comfort and to focus on his writing. He wanted to be an "invisible observer" of society. He wrote many essays for magazines like London Magazine.

He started a series of articles called "Table-Talk." These essays were written in a personal, conversational style. He shared his own memories and thoughts on life. Many of these essays are considered among the best in the English language. He wrote about the "Pleasure of Painting" and "On Going a Journey."

In London, Hazlitt faced the worst crisis of his life. In 1820, he rented rooms from a tailor named Micaiah Walker. He became very infatuated with Walker's daughter, Sarah. He wanted to marry her, but he needed a divorce from his wife. His wife agreed to a Scottish divorce, which allowed him to remarry.

The divorce was final in 1822. But Sarah Walker became distant. She eventually moved in with another person. Hazlitt wrote about this painful experience in a book called Liber Amoris; or, The New Pygmalion (1823). He published it anonymously.

This book was very personal and unlike his other works. Some critics liked it, but most were shocked. Even his friends were upset. Henry Crabb Robinson called it "disgusting." Liber Amoris gave his enemies more reasons to attack him. Hazlitt found it hard to find peace.

New Beginnings and European Travels

Returning to Philosophy

Even during this difficult time, Hazlitt continued to write. He wrote many essays for Table-Talk. Some were about his own life, like "On Reading Old Books." Others explored human nature, like "On People with One Idea." He also wrote about genius and creativity.

One famous essay from this period was "The Fight" (1822). It was a personal story about a boxing match. It was controversial because it was about a "low" subject. But it became one of his most popular essays.

Another essay, "On the Pleasure of Hating" (1823), showed his bitterness. He wrote about his own dislike for the world. He concluded by saying he hated himself for not hating the world enough.

His "Table-Talk" essays showed deep insights into human nature. They also explored the art of writing itself. Hazlitt explained his "Familiar Style." He aimed to use exact words to express his meaning. He often quoted Shakespeare and Milton. These essays were unique. They are now considered some of the best essays ever written in English.

In 1823, Hazlitt also published Characteristics. It was a collection of short, wise sayings. They were like the sayings of the French writer La Rochefoucauld. These sayings showed his disappointment with life.

Second Marriage and Travel

By early 1824, Hazlitt was starting to feel better. He still needed money. He kept writing for magazines like The Edinburgh Review. He also wrote about art.

In 1823, Hazlitt met Isabella Bridgwater. They married in Scotland in 1824. His English divorce was not recognized there. Isabella was a widow with her own money. This marriage offered Hazlitt an escape from loneliness and money worries. It seemed to be a marriage of convenience for both. Hazlitt never mentioned her in his writings. After three and a half years, they separated.

However, this marriage allowed them to travel. They toured Scotland. Then, in late 1824, they began a trip through Europe. This trip lasted over a year.

The Spirit of the Age

Before his European trip, Hazlitt wrote an essay called "Jeremy Bentham." It was the first in a series called "Spirits of the Age." These essays were collected in a book in 1825. It was called The Spirit of the Age: Or, Contemporary Portraits.

The book contained sketches of 25 important men of the time. These included philosophers, poets, and politicians. Hazlitt had observed many of them closely. Some he knew personally. He wrote about Bentham, Godwin, Malthus, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Byron. He also wrote about politicians like Wilberforce and Canning.

Hazlitt often showed these people in their daily lives. For example, he described Bentham walking in his garden. Hazlitt had lived near Bentham and observed him often.

He had thought deeply about many of their ideas for years. For example, his essay on Malthus was based on his earlier criticisms. He often compared people, showing their similarities and differences. He criticized Malthus's ideas for being unfair to the poor.

However, Hazlitt also praised good qualities. He said Malthus's writing style was "correct and elegant." He also softened his earlier harsh criticisms of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southey. He noted their positive traits. For example, he said Coleridge was the "most impressive talker" of his age.

Hazlitt also wrote about his friends Leigh Hunt and Lamb. He gave them gentle criticism along with praise. He even included an American writer, Washington Irving.

These 25 sketches painted a vivid picture of the age. Hazlitt also reflected on the "Spirit of the Age" as a whole. He felt it was an age of "talkers, and not of doers."

Some critics thought the essays were uneven. But many praised them. They admired Hazlitt's ability to capture a person with a few words. The book became one of Hazlitt's most successful.

Journey Through Europe

On September 1, 1824, Hazlitt and his wife started their European tour. They traveled from England to France, then to Italy. They visited Florence and Rome. Then they went to Venice, Verona, and Milan. From there, they went to Switzerland. Finally, they returned through Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. They arrived back in England in October 1825.

They stayed for three months in Paris and three months in Vevey, Switzerland. During these stops, Hazlitt wrote about his trip. These articles were published in The Morning Chronicle. They later became a book called Notes of a Journey through France and Italy (1826).

This trip was a break from his problems in England. Despite some illnesses and travel difficulties, Hazlitt enjoyed himself. He loved Paris. He explored museums, went to theatres, and walked the streets. He was especially happy to revisit the Louvre museum. He saw the masterpieces he had loved 20 years earlier.

In Paris, he befriended Henri Beyle, known as Stendhal. Stendhal admired Hazlitt's writings.

Hazlitt constantly observed and compared things. He described the beautiful scenery. For example, he wrote about Lake Geneva. He saw it with the eyes of both a painter and an art critic. He also thought about the differences between English and French people. He found that the French were very respectful in theatres. He also saw that culture was widespread among working-class people. He saw an "apple-girl in Paris...reading Racine and Voltaire."

He tried to be honest and changed his old ideas about the French. He realized that nations, like people, have a mix of good and bad qualities.

In Florence, he visited art galleries. He also became friends with Walter Savage Landor. He spent time with his old friend Leigh Hunt, who was living there.

Hazlitt had mixed feelings about Rome. At first, he was disappointed. He expected ancient monuments. But he saw many modern shops and buildings. He also found the art galleries disappointing at first. Eventually, he found much to admire. But there were too many distractions. He also found it hard to deal with the local people.

Venice fascinated him. He wrote, "You see Venice rising from the sea...with a mixture of awe and incredulity." He loved the palaces and the paintings by Titian and Veronese.

On the way home, he wanted to see Vevey in Switzerland. This town was the setting for Rousseau's novel La Nouvelle Héloïse. This love story reminded him of his own difficult love for Sarah Walker. He loved the area so much that he stayed there for three months. It was a peaceful place for him.

He continued to write in Vevey. He wrote "Merry England" there. He described sitting in a beautiful valley. He thought about happy moments from his life.

Returning to London in October was a bit of a letdown. The weather and food were not as good. He also had digestive problems. But he was happy to be home. He already planned to return to Paris.

Later Years and Legacy

Final Writings

Hazlitt settled back in London in late 1825. He continued to write for magazines. He wrote about his favorite topics. These included politics, plays, and human nature. He collected his essays for a book called The Plain Speaker. He also published his travel account.

His main goal was to write a biography of Napoleon. He wanted to write it from a liberal point of view. Walter Scott was writing his own book about Napoleon from a conservative view. Hazlitt wanted to offer a different side. He admired Napoleon as a hero of freedom.

Hazlitt was also interested in older artists. He often visited the painter James Northcote, who was about 80 years old. They talked about people, art, and life. Northcote was grumpy, but Hazlitt enjoyed his company. Hazlitt wrote down their conversations. He published them as "Boswell Redivivus." He admitted that some of Northcote's words were actually his own ideas.

When these conversations were published, some people were angry. Northcote denied saying some of the things. Hazlitt was in Paris at the time, working on his Napoleon book.

In one of their last conversations, Northcote told Hazlitt he had two faults. He said Hazlitt had a "quarrel with the world" and was careless. Hazlitt agreed that he had become cynical. He felt he had been treated unfairly. This conversation showed how Hazlitt saw his own life.

Focus on Napoleon

In August 1826, Hazlitt and his wife went to Paris again. He wanted to research his Napoleon biography. He hoped it would be his masterpiece.

However, it was hard to focus. His wife's money allowed them to live in a nice area. But he was distracted by visitors. He also couldn't access all the books he needed. His son visited, which caused arguments. This also strained his marriage.

His own books weren't selling well. So Hazlitt had to write many articles to pay for things. Still, some of these essays were excellent. One was "On the Feeling of Immortality in Youth" (1827).

He returned to London with his son in August 1827. He was shocked to learn his wife was leaving him. He moved into a small apartment. He struggled with poverty. He wrote many articles for money. He also continued working on his Napoleon book. He suffered from illnesses. The first two volumes of his Napoleon biography came out in 1828. But the publisher failed, causing more money problems.

The easy life he had talked about was gone. He was overwhelmed by poverty and illness. He was depressed because he hadn't found true love. He also couldn't finish his defense of Napoleon as he wanted.

His reputation had been ruined by Tory critics. One critic said Hazlitt had been "excommunicated from all decent society." His four-volume life of Napoleon was a financial failure. It also contained a lot of borrowed material. Hazlitt finished it just before he died. But he didn't live to see it fully published.

Last Days

Few details are known about Hazlitt's last years. He spent time in Winterslow, his favorite countryside spot. But he also needed to be in London for work. He visited old friends. He was often seen with his son and his son's fiancée. He kept writing articles to earn money.

In 1828, Hazlitt started reviewing plays again. He found great comfort in going to the theatre. He wrote an essay called "The Free Admission." He explained that the theatre helped him think about his past. He could "melt down years to moments" and enjoy life's pleasures without the pain.

He also returned to his philosophical ideas. He wrote about "Common Sense," "Originality," and "Envy." He summarized his life's work as a philosopher. He also started writing for The Edinburgh Review again. This helped him avoid hunger.

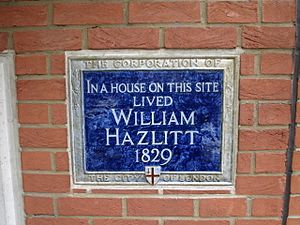

After a brief stay with his son, Hazlitt moved into a small apartment in Frith Street, Soho. He continued to write for various magazines. He was often sick and became more withdrawn. But he still wrote some notable essays. In "The Sick Chamber," he described how illness affected the mind.

In one of his last moments without pain, he wrote about reading. He said, "A book is the secret and sure charm." He felt books let us "into their souls and lay open to us the secrets of our own." He called them "the first and last, the most home-felt, the most heart-felt of our enjoyments."

His health worsened. News of the July Revolution in France in July 1830 cheered him up. But he was often too sick to see visitors. By September 1830, he was confined to bed. His son was with him. He died on September 18, 1830. His last words were reportedly, "Well, I've had a happy life."

William Hazlitt was buried in the churchyard of St Anne's Church, Soho in London. Only a few friends, including Charles Lamb, attended his funeral.

After His Death

After his death, Hazlitt's books went out of print. His reputation declined for a while. But in the late 1990s, people started to appreciate him again. His works were reprinted. Two major books about him were published: The Day-Star of Liberty by Tom Paulin (1998) and Quarrel of the Age by A. C. Grayling (2000).

Hazlitt's reputation has continued to grow. Many modern thinkers and scholars now see him as one of the greatest critics and essayists in the English language.

In 2003, his gravestone was restored. This happened after a campaign led by Ian Mayes and A. C. Grayling. Michael Foot unveiled the new memorial. A Hazlitt Society was also started. This society publishes a yearly journal called The Hazlitt Review.

The last place Hazlitt lived, on Frith Street in London, is now a hotel called Hazlitt's.

The novel The Cure for Love (1998) by Jonathan Bate was partly based on Hazlitt's life.

See also

In Spanish: William Hazlitt para niños

In Spanish: William Hazlitt para niños

- Napoleonist Syndrome

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |