Joseph Priestley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Priestley

|

|

|---|---|

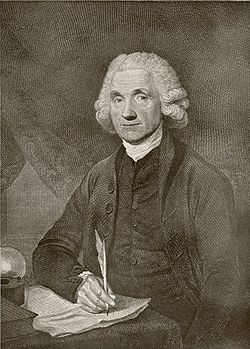

Priestley by William Artaud

|

|

| Born | 13 March 1733 |

| Died | 8 February 1804 Northumberland, Pennsylvania

|

Joseph Priestley was an English thinker from the 1700s. He was a theologian (someone who studies religion), a scientist, and a chemist. He also taught many subjects and wrote over 150 books and papers.

Many people know Priestley for discovering oxygen. He was the first to get oxygen gas by itself. However, other scientists like Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Antoine Lavoisier also played a big part in its discovery.

During his life, Priestley was famous for inventing soda water. He also wrote a lot about electricity and found several new "airs" (which we now call gases). His most famous discovery was "dephlogisticated air," which is what he called oxygen.

Priestley was a teacher and scholar his whole life. He helped improve how people taught. He wrote important books on English grammar and history. He also created some of the first useful timelines. These teaching books were very popular.

By 1801, Priestley became very sick and could no longer write or do experiments. He passed away on February 6, 1804, when he was 70 years old. He was buried in Riverview Cemetery in Northumberland, Pennsylvania. By the time he died, he was a member of almost every major science group in the Western world. He had also discovered many different substances.

Priestley's work is still remembered today. His discovery of oxygen was named a National Historic Chemical Landmark in 1994. This happened at his house in Northumberland, Pennsylvania. The American Chemical Society also gives out its highest award, the Priestley Medal, in his name.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Joseph Priestley was born in Birstall, England. His family were English Dissenters, meaning they did not follow the official Church of England. He was the oldest of six children. His father, Jonas Priestley, worked with cloth.

When Joseph was about one year old, he went to live with his grandfather. He came back home five years later after his mother died. In 1741, his father remarried, and Joseph then went to live with his aunt and uncle, Sarah and John Keighley. They were wealthy and had no children of their own.

Joseph was a very smart child. By age four, he could perfectly recite a long religious text. His aunt wanted him to have the best education so he could become a minister. He went to local schools and learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.

Around 1749, Priestley got very sick. He thought he was going to die. He had been raised as a strict Calvinist, a type of Christian. This made him question his religious beliefs.

His illness left him with a permanent stutter. Because of this, he decided not to become a minister right away. He planned to join a relative in business in Lisbon. So, he studied French, Italian, German, Aramaic, and Arabic. He also learned higher math, natural philosophy (early science), and logic from his tutor, Reverend George Haggerstone.

In 1752, Priestley went to Daventry Academy, a school for Dissenters. Since he had already read so much, he didn't have to do the first two years of classes.

Teacher and Historian

In 1761, Priestley moved to Warrington in Cheshire. He became a tutor of modern languages and public speaking at the town's Dissenting academy. He would have preferred to teach math and science. He quickly made friends in Warrington.

On June 23, 1762, Priestley married Mary Wilkinson.

All the books Priestley wrote while in Warrington were about history. He believed history was important for both success in life and religious growth.

In his book Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life (1765) and Lectures on History and General Policy (1788), Priestley said that young people's education should prepare them for their future jobs. He suggested learning modern languages instead of old ones, and modern history instead of ancient history. He also supported educating middle-class women, which was unusual for his time.

Some experts say Priestley was the most important English writer on education between John Locke in the 1600s and Herbert Spencer in the 1800s. His Lectures on History was very popular. Many schools, including Brown, Princeton, Yale, and Cambridge, used it.

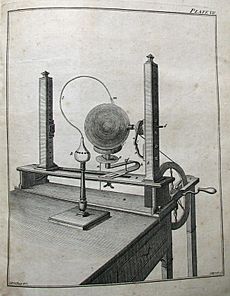

The atmosphere at Warrington encouraged Priestley's interest in science. He gave talks on anatomy and did experiments with temperature. Even with his busy teaching schedule, he decided to write a history of electricity.

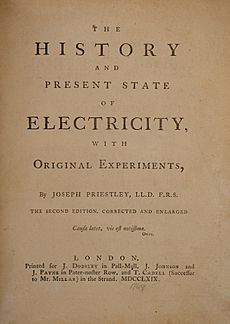

In 1767, his 700-page book The History and Present State of Electricity was published and received good reviews. The first part of the book tells the story of electricity studies up to 1766. The second, more important part describes the ideas about electricity at the time and suggests new research.

Perhaps because Mary Priestley was unwell or because of money problems, Priestley and his family moved from Warrington to Leeds in 1767. He became a minister at Mill Hill Chapel. Two more sons, Joseph junior and William, were born in Leeds.

Scientist: Electricity, Optics, and Soda Water

Even though Priestley said science was just a hobby, he took it seriously. In his History of Electricity, he wrote that scientists help make "mankind" safe and happy. Priestley's science was very practical. He didn't often worry about deep theories. His good friend, Benjamin Franklin, was his role model. When he moved to Leeds, Priestley kept doing his experiments with electricity and chemistry.

Between 1767 and 1770, he sent five papers about his early experiments to the Royal Society. These papers looked at electrical sparks and how different types of charcoal conduct electricity. Later, his experiments focused on chemistry and gases.

In 1772, Priestley published the first part of The History and Present State of Discoveries Relating to Vision, Light and Colours, also known as his Optics. He paid close attention to the history of optics and explained early experiments well. Unlike his electricity book, this one was not popular and only had one printing. The cost of researching and publishing Optics made Priestley decide to stop writing histories of science.

Priestley was considered for a job as an astronomer on James Cook's second voyage around the world. He wasn't chosen, but he still helped the trip. He gave the crew a way to make carbonated water. He thought it might help cure scurvy, a disease. He then published a small book called Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air (1772). Priestley didn't make money from soda water, but others like J. J. Schweppe became rich from it. Because of this discovery, Priestley is called "the father of the soft drink". The company Schweppes even calls him "the father of our industry." In 1773, the Royal Society gave Priestley the Copley Medal for his scientific work.

Priestley's friends wanted him to have a more stable job. In 1772, Lord Shelburne asked Priestley to teach his children and be his helper. Priestley didn't want to leave his church job, but he accepted. He left Mill Hill Chapel in December 1772. In 1773, the Priestleys moved to Calne in Wiltshire.

Discovering Oxygen

Priestley's time in Calne was when he did most of his scientific research. It was also his most successful scientific period. His experiments were almost all about "airs" (gases). From this work came his most important science books: the six volumes of Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1774–86).

In August 1774, he found an "air" that seemed completely new. But he couldn't study it more because he was going on a trip to Europe with Shelburne. In Paris, Priestley showed the experiment to others, including the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier. After returning to Britain in January 1775, he kept experimenting. He discovered "vitriolic acid air" (sulphur dioxide, SO2).

In March, he wrote to several people about the new "air" he found in August. One of these letters was read to the Royal Society. A paper about the discovery, called "An Account of further Discoveries in Air," was published. Priestley called the new substance "dephlogisticated air." He made it by using a burning glass to focus the sun's rays on a sample of mercuric oxide.

He first tested it on mice. They surprised him by living much longer in this new air than in regular air. Then he tried it himself. He wrote that it was "five or six times better than common air for the purpose of respiration." He had discovered oxygen gas (O2).

Priestley put his oxygen paper and others into a second book, Experiments and Observations on Air, published in 1776.

In his paper "Observations on Respiration and the Use of the Blood," Priestley was the first to suggest a link between blood and air.

Around 1779, Priestley and Shelburne had a disagreement. The exact reasons are not clear. Priestley thought about moving to America. But he decided to accept an offer to be a minister in Birmingham.

Life in Birmingham (1780–1791)

In 1780, the Priestley family moved to Birmingham. They had a happy ten years there, surrounded by old friends. But in 1791, they were forced to leave because of angry mobs. These events became known as the Priestley Riots.

Priestley accepted the minister job at New Meeting. He only had to preach and teach on Sundays. This gave him time for his writing and science experiments. Just like in Leeds, Priestley started classes for the young people in his church. By 1781, he was teaching 150 students. Priestley's salary was not very high, so friends and supporters gave him money and supplies to help with his research. In 1782, he was chosen as an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Life in Pennsylvania (1794–1804)

Friends of Joseph and Mary Priestley encouraged them to leave Britain. They suggested moving to France or the new United States.

As relations between England and France got worse, moving to France became impossible. After war was declared in 1793, Priestley's sons Harry and Joseph left England for America in August 1793. Finally, Priestley himself followed with his wife, sailing to America in April 1794.

Priestley kept working on his educational projects, which were always important to him. He helped start the "Northumberland Academy" and gave his library to the new school. He wrote letters to Thomas Jefferson about how to set up a university. Jefferson used this advice when he founded the University of Virginia. Jefferson and Priestley became close friends. When Priestley finished his book General History of the Christian Church, he dedicated it to President Jefferson.

Priestley tried to continue his scientific work in America. He had support from the American Philosophical Society, which he had joined in 1785. Even though Priestley did fewer experiments, his presence made Americans more interested in chemistry.

By 1801, Priestley became too sick to write or do experiments. He died on February 6, 1804, at age 70. He was buried at Riverview Cemetery in Northumberland, Pennsylvania.

Priestley's gravestone reads:

Return unto thy rest, O my soul, for the

Lord hath dealt bountifully with thee.

I will lay me down in peace and sleep till

I awake in the morning of the resurrection.

Priestley's Legacy

When Joseph Priestley died in 1804, he was a member of almost every major scientific group in the Western world. He had discovered many new substances. A French scientist named George Cuvier praised Priestley's discoveries. However, Cuvier also noted that Priestley never accepted the new ideas about chemistry at the time. He called Priestley "the father of modern chemistry [who] never acknowledged his daughter."

Priestley wrote more than 150 books and papers. These covered many topics, from politics to education to religion and science. He inspired British reformers in the 1790s. He also helped create Unitarianism, a type of Christian faith. Many thinkers, scientists, and poets were influenced by his ideas.

Priestley is remembered in the towns where he taught and served as a minister. Two schools are named after him: Priestley College in Warrington and Joseph Priestley College in Leeds. An asteroid, 5577 Priestley, discovered in 1986, is also named in his honor.

Statues of Priestley can be found in Birstall, Leeds City Square, and Birmingham. Plaques honoring him are in Birmingham, Calne, and Warrington. The main chemistry labs at the University of Leeds were renamed the Priestley Laboratories in 2006. In 2016, the University of Huddersfield renamed its Applied Sciences building the Joseph Priestley Building.

Since 1952, Dickinson College in Pennsylvania has given the Priestley Award. It goes to a "distinguished scientist whose work has contributed to the welfare of humanity." Priestley's discovery of oxygen is recognized as a National Historic Chemical Landmark. This happened on August 1, 1994, at the Priestley House in Pennsylvania. Similar recognition was given in 2000 at Bowood House in England. The American Chemical Society also gives its highest award, the Priestley Medal, in his name.

Several of Priestley's family members became doctors, including the famous American surgeon James Taggart Priestley II.

Images for kids

-

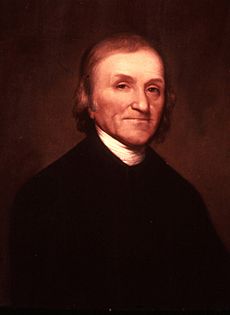

A portrait of Priestley by Henry Fuseli (around 1783)

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Priestley para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Priestley para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |