Priestley Riots facts for kids

The Priestley Riots, also called the Birmingham Riots of 1791, happened in Birmingham, England. These riots lasted from July 14 to July 17, 1791. The main targets were religious dissenters, especially Joseph Priestley. He was a well-known figure in both politics and religion.

People were angry for many reasons. These included arguments over books for the public library. There were also disagreements about Dissenters wanting full civil rights. Their support for the French Revolution also made many people upset.

The riots began with an attack on the Royal Hotel, Birmingham. This was where a dinner was held to support the French Revolution. After that, the rioters attacked or burned many places. They targeted four Dissenting chapels, twenty-seven houses, and several businesses. They burned homes and chapels of Dissenters. They also attacked homes of people linked to Dissenters, like members of the scientific Lunar Society.

The government of Prime Minister William Pitt did not start the riots. However, they were slow to help the Dissenters. Local officials seemed to have helped plan the riots. Later, they were not keen to punish the riot leaders. Industrialist James Watt said the riots "divided [Birmingham] into two parties who hate one another mortally". Many who were attacked left Birmingham. This made the city more traditional than before.

Contents

Why the Riots Happened

Birmingham's History of Riots

Birmingham was known for riots in the 1700s. These riots had many causes. In 1714 and 1715, mobs attacked Dissenters. Dissenters were Protestants who did not follow the Church of England. In 1751 and 1759, Quakers and Methodists were attacked. Large crowds also gathered during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in 1780. Mobs protested high food prices in 1766, 1782, 1795, and 1800.

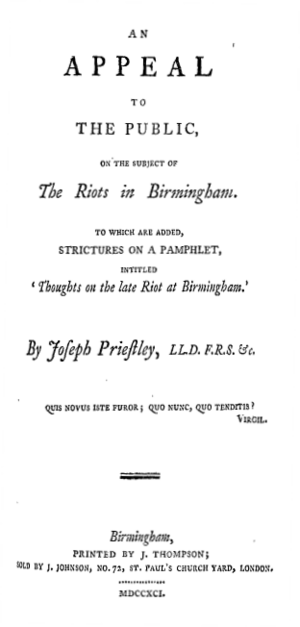

Before the late 1780s, religious differences did not bother Birmingham's leaders. Dissenters and Anglicans lived together peacefully. They worked on town projects and shared scientific interests. They were united against unruly lower-class people. But after the riots, Joseph Priestley said this peace was not real. He wrote that arguments over the local library, Sunday Schools, and church attendance had divided them.

Historian William Hutton agreed. He said five things caused religious tension. These included arguments over Priestley's books in the library. There were also concerns about Dissenters trying to change laws. These laws stopped Dissenters from attending universities or holding public office. Priestley's religious views also caused anger. A "fiery hand-bill" and a dinner celebrating the French Revolution also added to the problems.

When Dissenters tried to change the laws, the peace among the town's leaders ended. Unitarians like Priestley led this effort. Traditional Anglicans became worried and angry. Groups formed to stop Dissenters and French Revolutionary ideas. Dissenters mostly supported the French Revolution. They wanted to question the role of monarchy in government.

One month before the riots, Priestley tried to start a reform group. It would have supported universal suffrage (everyone voting) and shorter Parliaments. This effort failed, but it made tensions in Birmingham worse.

Besides religious and political differences, there were economic complaints. Lower-class rioters and their upper-class Anglican leaders were angry at middle-class Dissenters. They were jealous of the Dissenters' growing wealth. These Dissenters were often successful industrialists. Priestley himself wrote a pamphlet on how to get the most work from the poor for the least money. This did not make him popular with the poor.

Britain and the French Revolution

The debate in Britain about the French Revolution lasted from 1789 to 1795. At first, many people thought France would follow Britain's own Glorious Revolution. Many Britons liked the Revolution. Most celebrated the storming of the Bastille in 1789. They believed France's absolute monarchy should be replaced by a more democratic government. Supporters hoped Britain's system would also be reformed. They wanted more people to vote and to fix unfair voting areas.

After Edmund Burke wrote Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), a debate started. Burke supported the French upper class, which surprised many. He had supported the American colonists against Britain. Burke supported traditional rule and the Church. But liberals like Charles James Fox supported the Revolution. They wanted individual freedoms and religious tolerance. Radicals like Priestley, William Godwin, Thomas Paine, and Mary Wollstonecraft wanted even more change. They pushed for a republic and changes to land ownership.

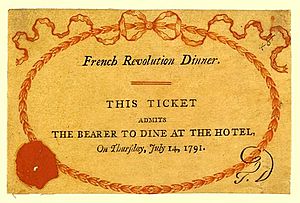

Signs of Trouble

On July 11, 1791, a Birmingham newspaper announced a dinner. It would be held on July 14 at the Royal Hotel, Birmingham. This dinner was to celebrate the second anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The invitation asked "any Friend to Freedom" to come.

The notice said:

A number of gentlemen intend dining together on the 14th instant, to commemorate the auspicious day which witnessed the emancipation of twenty-six millions of people from the yoke of despotism, and restored the blessings of equal government to a truly great and enlightened nation; with whom it is our interest, as a commercial people, and our duty, as friends to the general rights of mankind, to promote a free intercourse, as subservient to a permanent friendship.

Any Friend to Freedom, disposed to join the intended temperate festivity, is desired to leave his name at the bar of the Hotel, where tickets may be had at Five Shillings each, including a bottle of wine; but no person will be admitted without one.

Dinner will be on table at three o'clock precisely.

Next to this notice was a threat. It said "an authentic list" of those who attended would be published. On the same day, a very revolutionary handbill appeared. Its author was James Hobson, but this was not known at the time. Town officials offered 100 guineas for information about the handbill. The Dissenters had to say they knew nothing about it.

By July 12, it was clear there would be trouble at the dinner. On the morning of July 14, graffiti appeared around town. It said things like "destruction to the Presbyterians" and "Church and King for ever". Because of this, Priestley's friends told him not to go to the dinner. They feared for his safety.

The Riots Begin: July 14

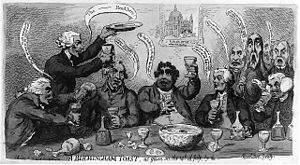

About 90 people who supported the French Revolution came to the dinner on July 14. The dinner was led by James Keir, an Anglican industrialist. He was also a member of the Lunar Society of Birmingham. When guests arrived, 60 or 70 protesters met them. The protesters shouted "no popery" and then left for a short time.

By the time the dinner ended, hundreds of people had gathered. The rioters were mostly workers from Birmingham. They threw stones at the guests and attacked the hotel. The crowd then went to a Quaker meeting-house. But someone shouted that Quakers "never trouble themselves with anything". So, they attacked the New Meeting chapel instead. Priestley was the minister there. The New and Old Meeting Houses, both Dissenting chapels, were set on fire.

The rioters then went to Priestley's home, Fairhill, in Sparkbrook. Priestley and his wife barely had time to escape. They hid with different Dissenting friends during the riots. Priestley later wrote about seeing the attack from a distance:

It being remarkably calm, and clear moon-light, we could see to a considerable distance, and being upon a rising ground, we distinctly heard all that passed at the house, every shout of the mob, and almost every stroke of the instruments they had provided for breaking the doors and the furniture. For they could not get any fire, though one of them was heard to offer two guineas for a lighted candle; my son, whom we left behind us, having taken the precaution to put out all the fires in the house, and others of my friends got all the neighbours to do the same. I afterwards heard that much pains was taken, but without effect, to get fire from my large electrical machine, which stood in the library.

His son, William, stayed to protect the home. But the rioters took over. The property was looted and burned to the ground. Priestley's valuable library, science lab, and writings were mostly lost in the fire.

Continuing Riots: July 15, 16, and 17

The Earl of Aylesford tried to stop the violence on the night of July 14. But he could not control the crowd, even with other officials helping. On July 15, the mob freed prisoners from the local jail. The prison keeper tried to get people to help stop the mob. But many of them joined the rioters instead.

The crowd destroyed John Ryland's home and Baskerville House. When new police officers arrived, the mob attacked and disarmed them. One man was killed. Local officials did nothing more to stop the mob. They did not read the Riot Act until the army arrived on July 17. Other rioters burned down banker John Taylor's home at Bordesley Park.

On July 16, several homes were ransacked or burned. These included the homes of Joseph Jukes, John Coates, John Hobson, Thomas Hawkes, and John Harwood. The Baptist Meeting at Kings Heath, another Dissenting chapel, was also destroyed. William Russell and William Hutton tried to defend their homes. But the men they hired refused to fight the mob. Hutton later wrote about the events:

I was avoided as a pestilence; the waves of sorrow rolled over me, and beat me down with multiplied force; every one came heavier than the last. My children were distressed. My wife, through long affliction, ready to quit my own arms for those of death; and I myself reduced to the sad necessity of humbly begging a draught of water at a cottage!...In the morning of the 15th I was a rich man; in the evening I was ruined.

When the rioters reached John Taylor's other house, Moseley Hall, they were careful. They moved all the furniture of the current resident, Lady Carhampton, out of the house. She was a relative of George III. Only then did they burn the house. They were specifically targeting those who disagreed with the king and the Church of England.

The homes of George Russell, Samuel Blyth, Thomas Lee, and a Mr. Westley were attacked on July 15 and 16. Manufacturer and Quaker Samuel Galton saved his home. He bribed the rioters with ale and money.

By 2 p.m. on July 16, the rioters left Birmingham. They headed towards Kings Norton and Kingswood Chapel. One group of rioters was estimated to be 250 to 300 people. They burned Cox's farm at Warstock. They also looted and attacked Mr. Taverner's home. When they reached Kingswood, Warwickshire, they burned the Dissenting chapel and its house. By this time, Birmingham had stopped all business.

Reports say the mob's last big attack was around 8 p.m. on July 17. About 30 main rioters attacked the home of William Withering. He was an Anglican who attended the Lunar Society with Priestley. But Withering, with hired men, managed to fight them off. When the army finally arrived on July 17 and 18, most rioters had left. There were rumors of mobs destroying property in Alcester and Bromsgrove.

In total, four Dissenting churches were badly damaged or burned. Twenty-seven homes were attacked, many looted and burned. The "Church-and-King" mob started by attacking those who celebrated the Bastille. They ended up targeting all Dissenters and members of the Lunar Society.

Aftermath and Trials

Priestley and other Dissenters blamed the government for the riots. They believed William Pitt had caused them. However, it seems local Birmingham officials organized the riots. Some rioters acted in a planned way. They seemed to be led by local officials during the attacks. This led to accusations that the riots were planned. Some Dissenters found out their homes would be attacked days before it happened. This made them think there was a list of victims. A small group of about thirty "hard core" rioters directed the mob. They stayed sober during the three to four days of rioting. Unlike hundreds of others, they could not be bribed to stop.

If Birmingham's Anglican leaders planned to attack Dissenters, it was likely the work of Benjamin Spencer, a local minister. Also involved were Joseph Carles, a local official, and John Brooke (1755-1802), a lawyer. Carles and Spencer were there when the riot started but did not try to stop it. Brooke seemed to lead the rioters to the New Meeting chapel. Witnesses said that officials promised rioters protection. This was as long as they only attacked meeting-houses and left people and property alone. The officials also refused to arrest any rioters. They released those who had been arrested.

The national government told local officials to prosecute the riot leaders. But these local officials were slow to act. When they finally had to try the leaders, they scared witnesses. They also made the trials unfair. Only seventeen of the fifty rioters charged were brought to trial. Four were found guilty. One was pardoned, two were hanged, and one was sent to Botany Bay. But Priestley believed these men were found guilty for other reasons, not just for rioting.

King George III had to send troops to stop the riots. But he said, "I cannot but feel better pleased that Priestley is the sufferer for the doctrines he and his party have instilled, and that the people see them in their true light." The national government made local residents pay for the damaged property. The total was about £23,000. However, this process took many years. Most residents received much less than their property was worth.

After the riots, Birmingham was "divided into two parties who hate one another mortally," according to industrialist James Watt. Priestley wanted to return and give a sermon. But his friends told him it was too dangerous.

The riots showed that Birmingham's Anglican upper class was willing to use violence. They used it against Dissenters, whom they saw as possible revolutionaries. They also did not mind stirring up a mob that could become uncontrollable. Many of those attacked left Birmingham. As a result, the town became much more traditional after the riots. Supporters of the French Revolution decided not to hold a dinner the next year.

Images for kids

-

Joseph Priestley's home, Fairhill at Sparkbrook, Birmingham, after its destruction (etching by William Ellis after a drawing by P. H. Witton)

-

William Russell's home, Showell Green, Sparkhill after its destruction. (Etching by William Ellis, after a drawing by P. H. Witton)

-

James Gillray's cartoon mocking the 14 July dinner

See also

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |